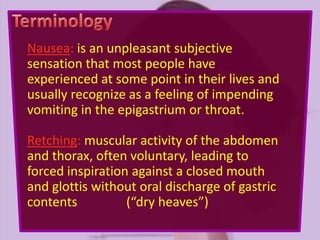

Nausea, retching, vomiting, regurgitation, and rumination are interrelated sensations and actions involving the gastrointestinal system, coordinated by the emetic center in the brain. Various clinical presentations of vomiting can indicate different underlying causes, including metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal obstructions, and neurological conditions. Treatment strategies prioritize restoring fluid and electrolytes, addressing nutritional needs, and employing symptomatic relief, while identifying and treating the underlying cause whenever possible.