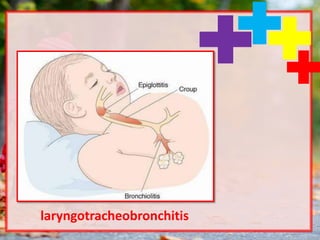

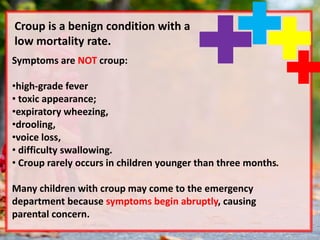

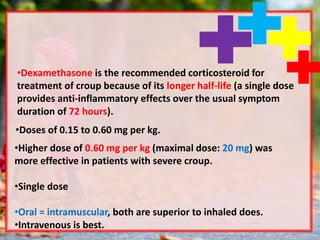

Croup is a common respiratory illness in children, accounting for a significant portion of emergency department visits. The illness is primarily viral, with a range of symptoms including a barking cough, respiratory distress, and low-grade fever, and is mostly benign with low mortality rates. Management typically involves corticosteroids to reduce symptoms, with additional therapies like epinephrine used for severe cases.