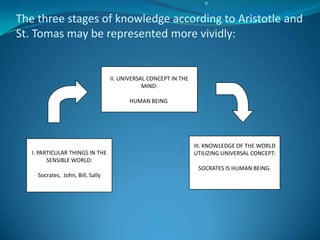

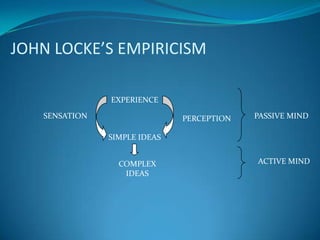

The document summarizes key aspects of empiricism according to philosophers like Aristotle, Aquinas, and Locke. It discusses how empiricists believe that all knowledge is derived from sense experience. Aristotle believed we develop universal ideas from our experiences with particular objects through induction. For Aquinas, the intellect can abstract the essence of things from our senses. Locke viewed the mind as initially blank, with ideas developing from sensation and reflection. He distinguished between simple and complex ideas.