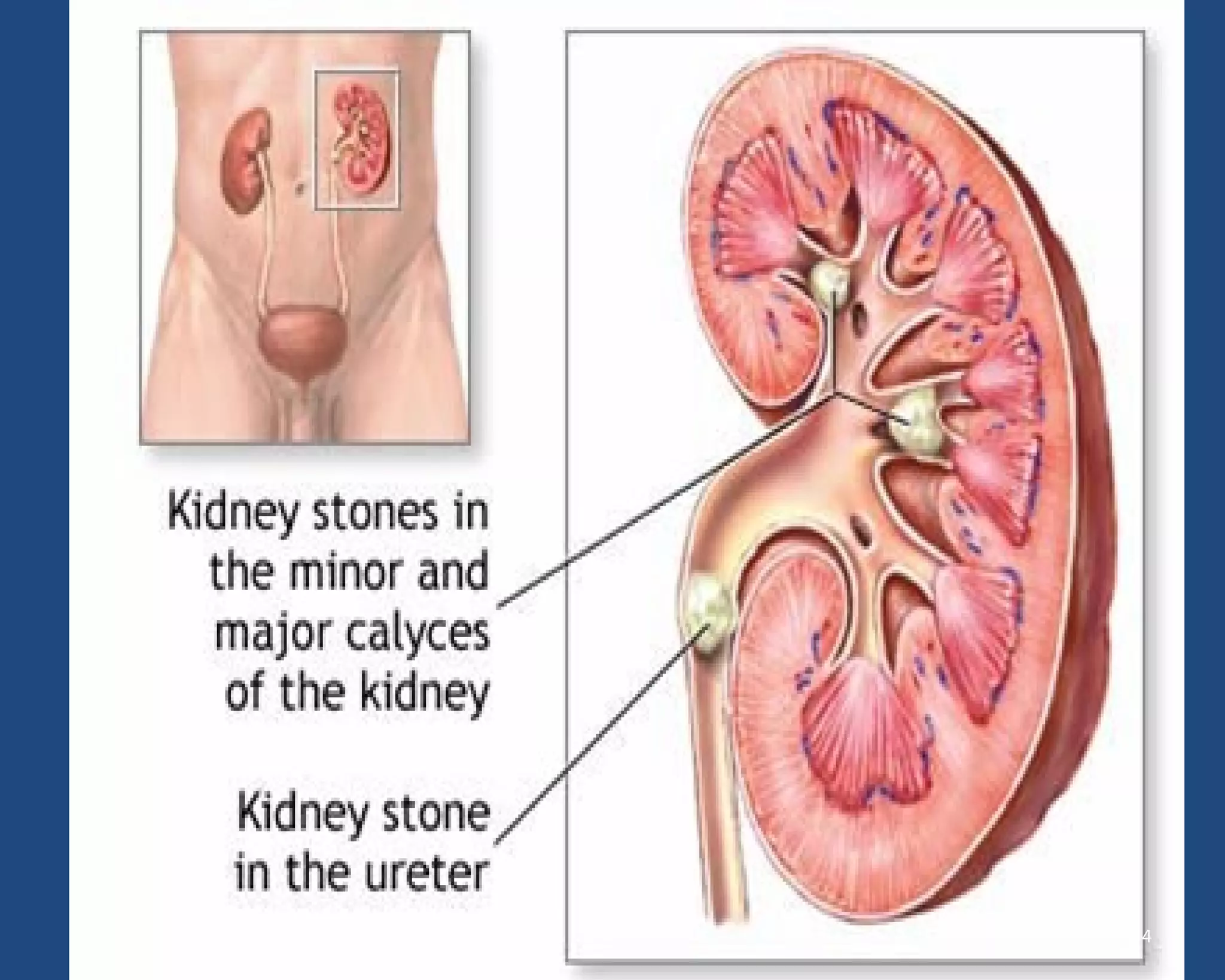

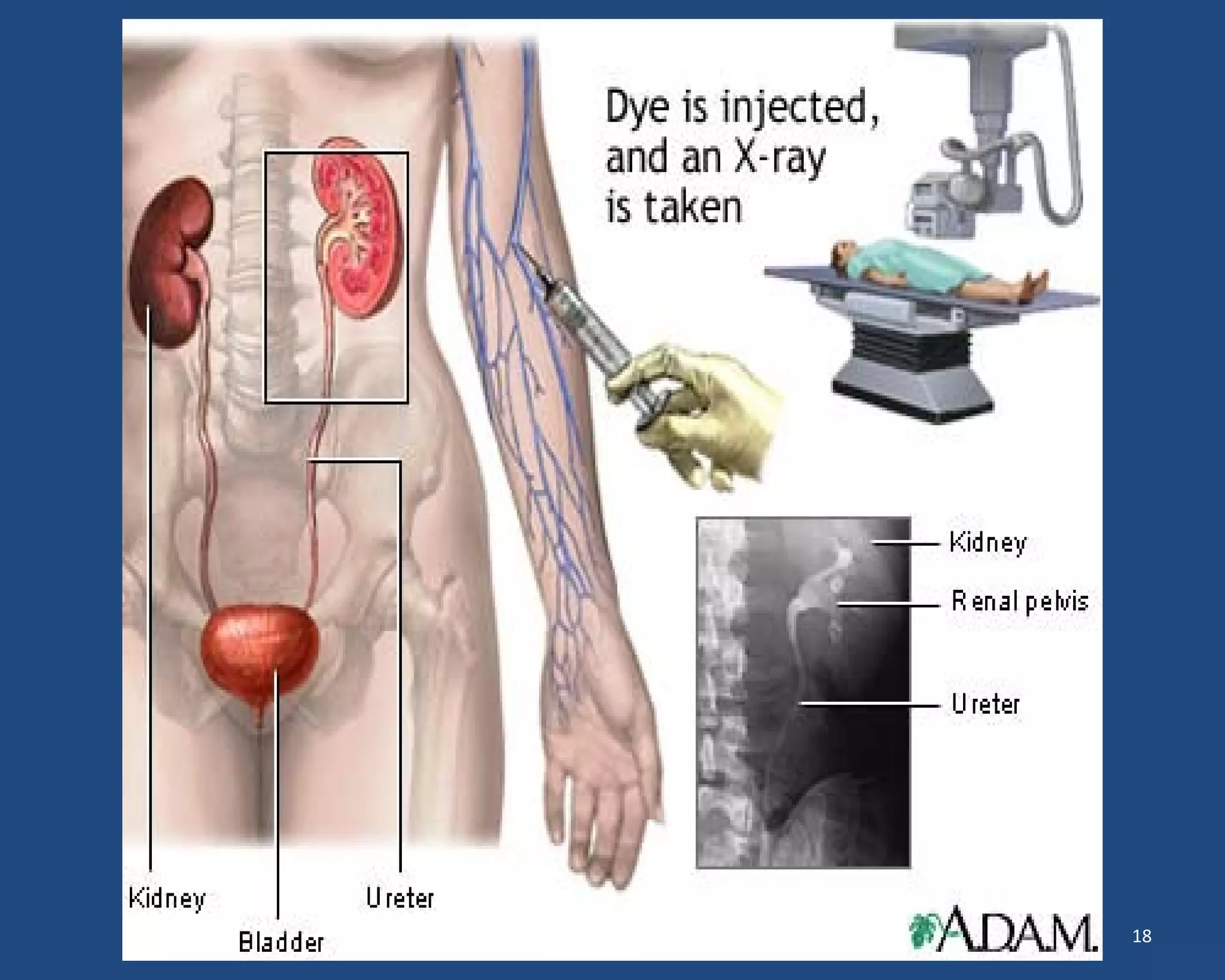

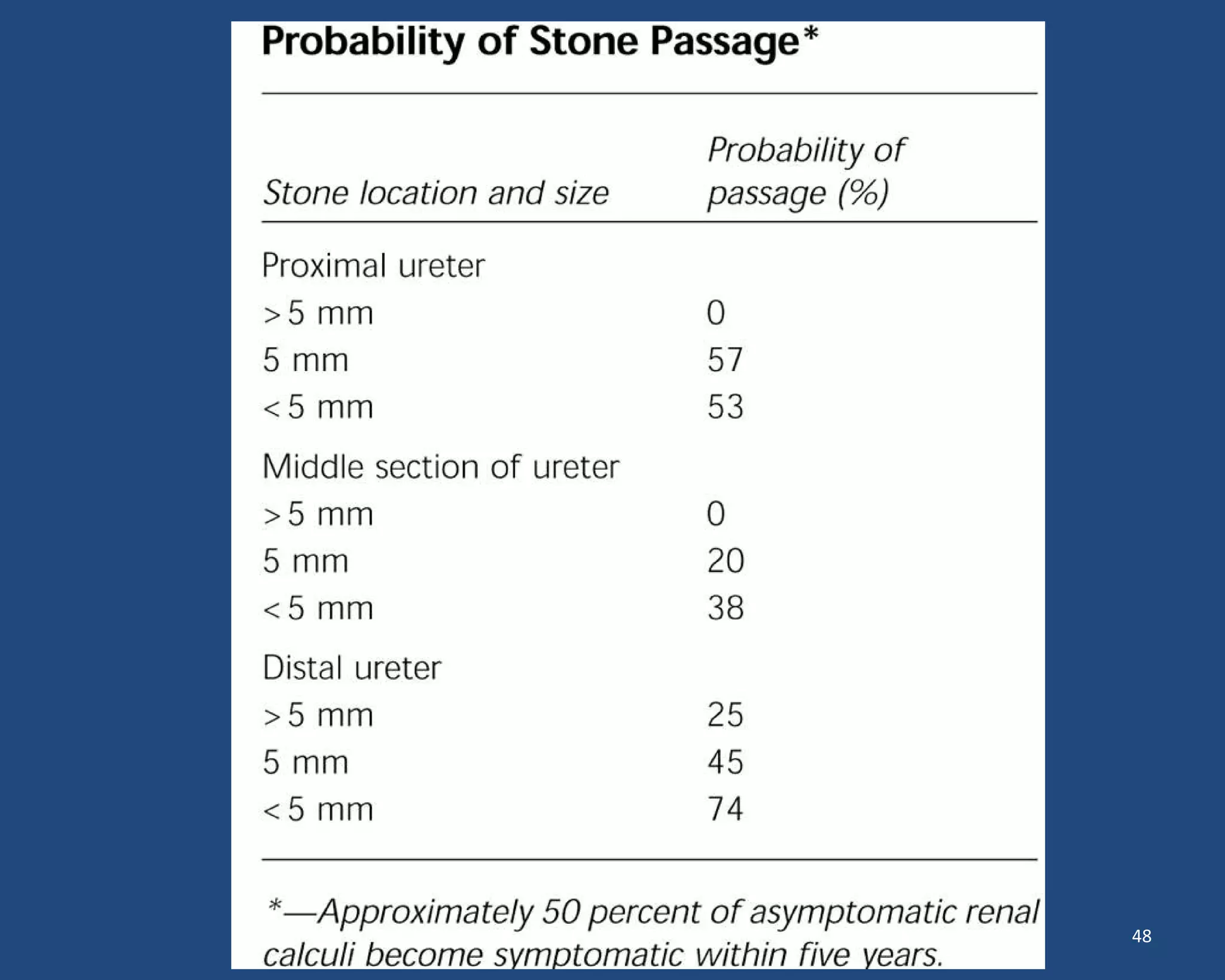

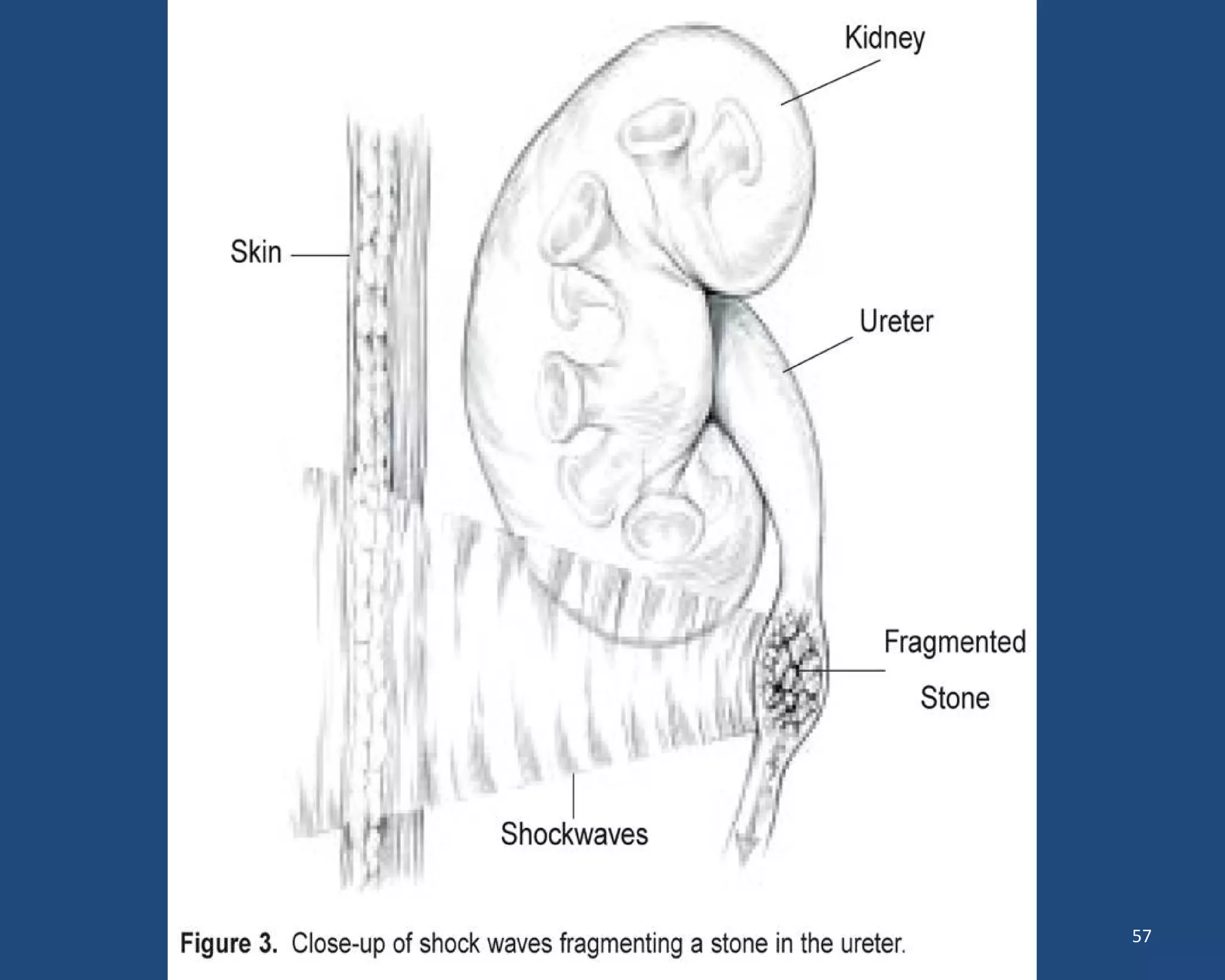

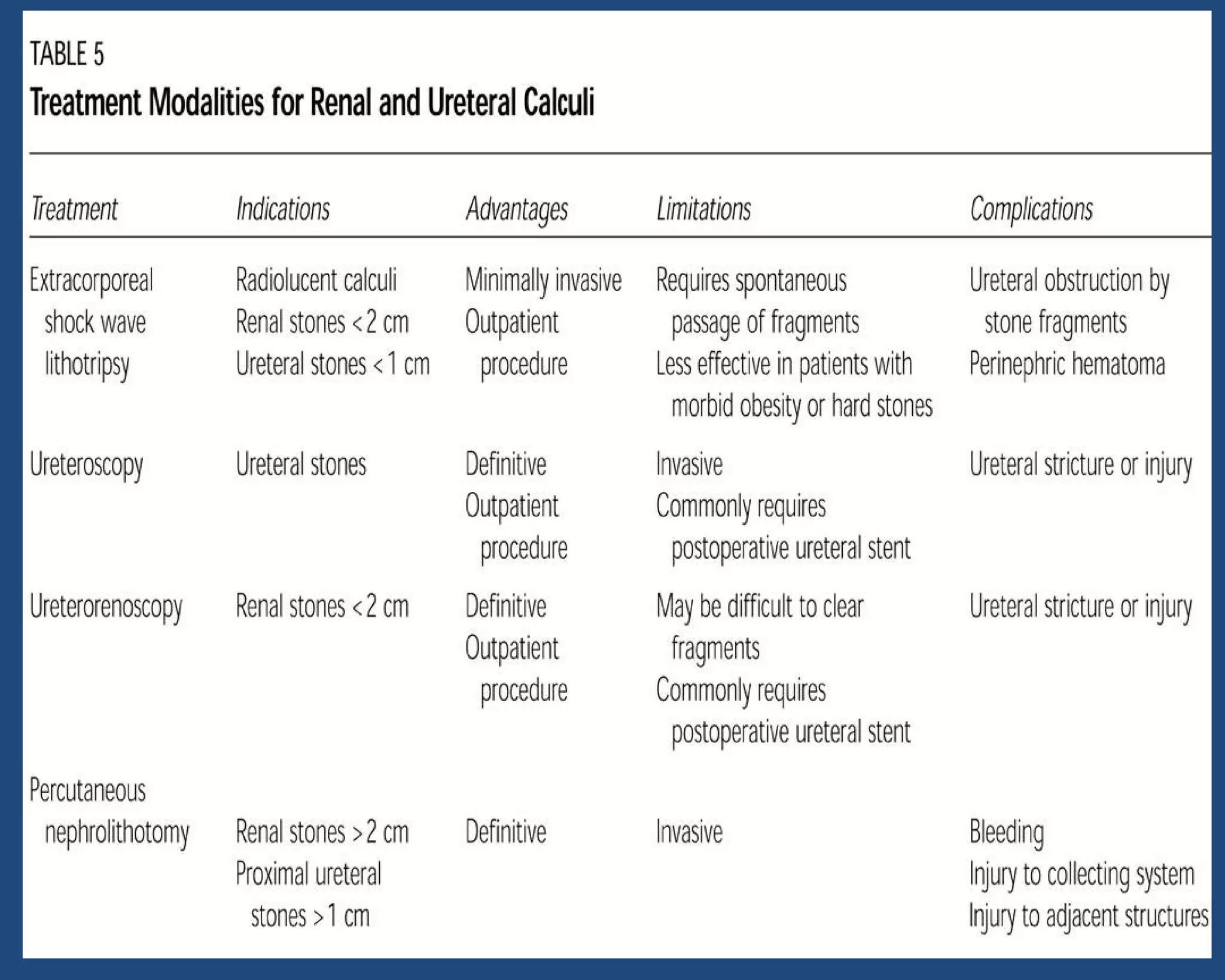

This document discusses the diagnosis and management of kidney stones (urolithiasis). It covers the epidemiology, types, diagnosis, and treatment options for kidney stones. For diagnosis, it recommends non-contrast CT scanning as the most sensitive test. For treatment, it describes medical expulsive therapy using drugs to help pass small stones, as well as minimally invasive procedures like ESWL, PNL, and ureteroscopy for larger stones. Factors like stone size, location, and composition are considered when selecting a treatment approach.