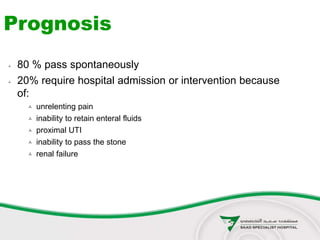

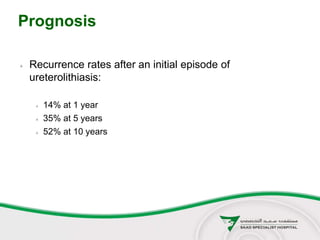

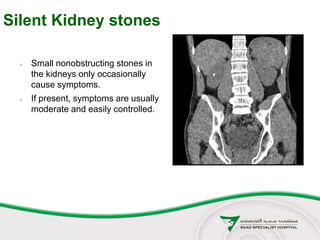

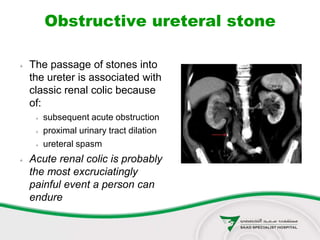

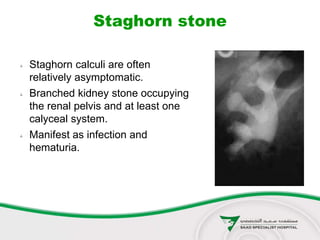

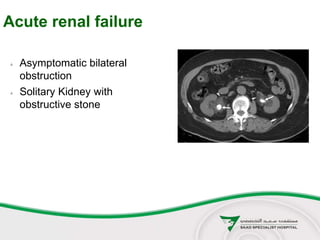

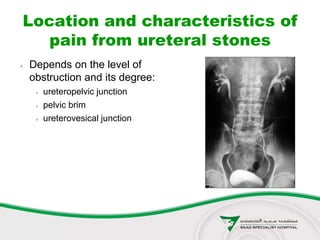

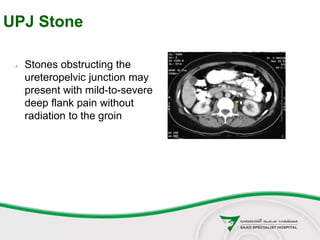

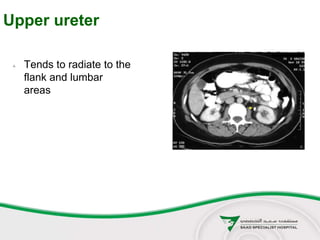

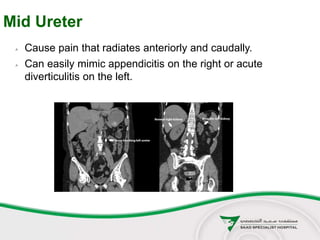

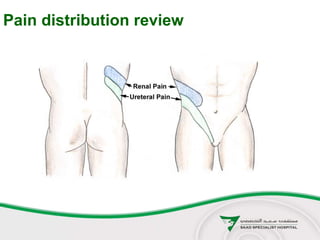

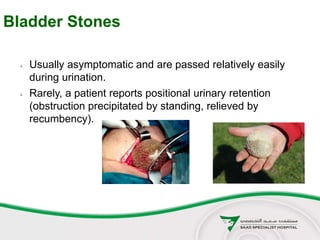

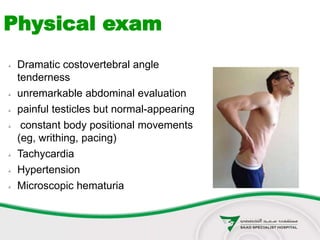

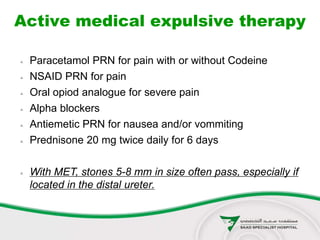

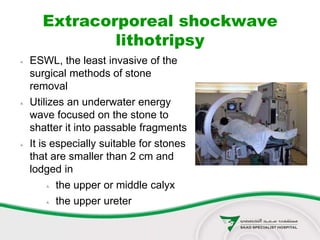

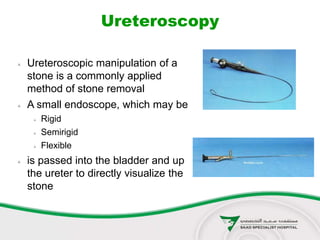

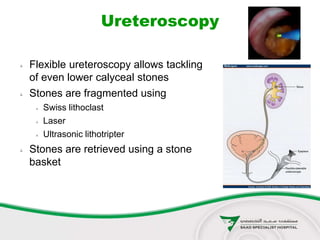

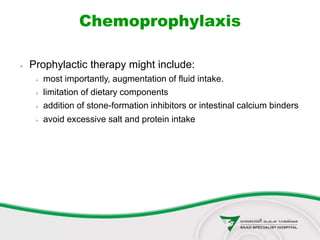

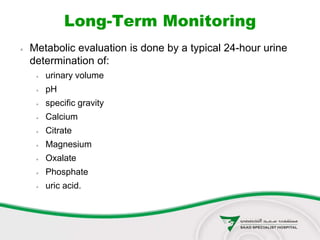

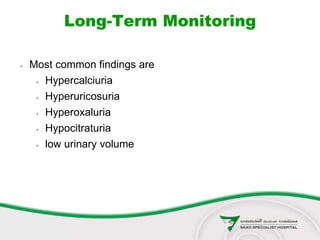

This document discusses urolithiasis (kidney stones). It begins by defining urolithiasis and noting its prevalence and cost. It then covers the epidemiology, types, symptoms, diagnosis, and management of kidney stones. The main points are that kidney stones can form anywhere in the urinary tract, have a lifetime risk of 2-20% depending on location, and are most commonly treated through active medical expulsion or minimally invasive surgeries like ESWL or ureteroscopy. Surgical intervention is indicated for large or obstructing stones, infection, or if conservative measures fail.