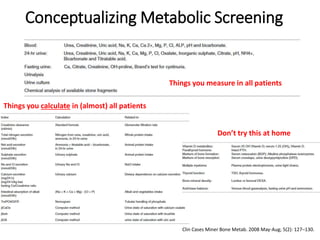

This document discusses urinary stone disease (kidney stones). It reviews the epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis and types of kidney stones. It also reviews guidelines for management from the American Urological Association. The main points are:

- Kidney stone prevalence is increasing worldwide, especially for calcium stones. Risk factors include metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

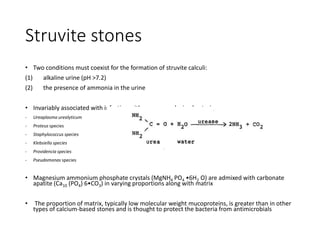

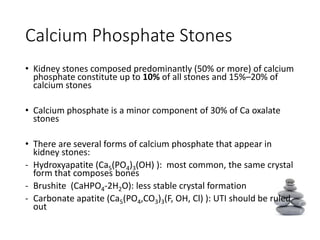

- The major stone types are calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, uric acid and struvite. Composition depends on urine composition and risk factors.

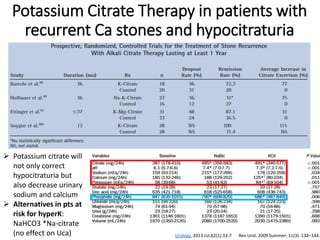

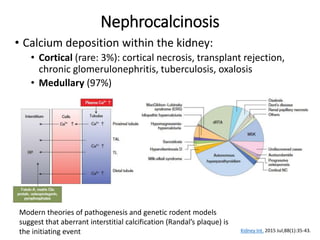

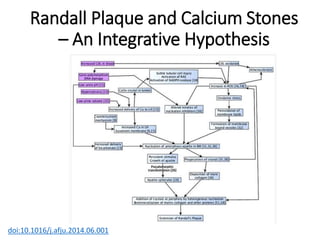

- Pathogenesis involves supersaturation of urine leading to crystallization of stone-forming substances. Hypocitraturia and hyperoxaluria are common contributing factors.

-

![Follow up II

25. Clinicians should obtain a repeat stone analysis,

when available, especially in patients not responding

to treatment. (Expert Opinion)

26. Clinicians should monitor patients with struvite

stones for reinfection with urease-producing

organisms and utilize strategies to prevent such

occurrences. (Expert Opinion)

27. Clinicians should periodically obtain follow-up

imaging studies to assess for stone growth or new

stone formation based on stone activity (plain

abdominal imaging, renal ultrasonography or low

dose computed tomography [CT]). (Expert Opinion)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/urinarystonedisease-160424081231/85/Urinary-stone-disease-41-320.jpg)