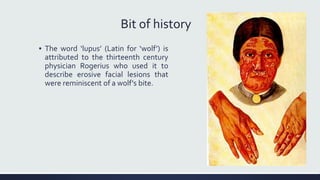

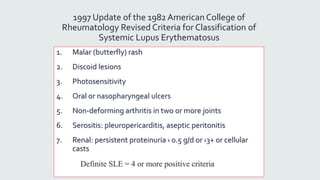

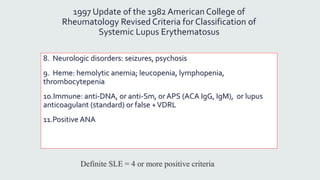

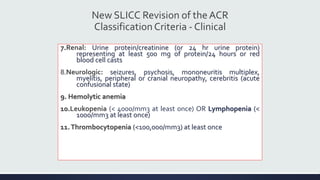

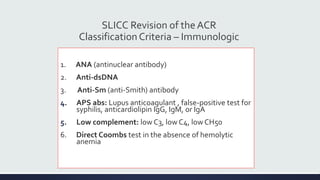

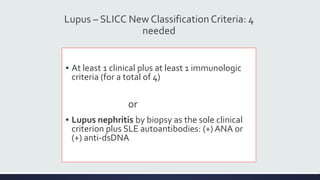

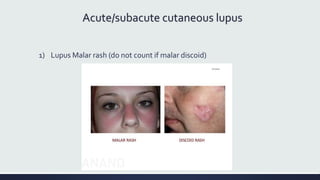

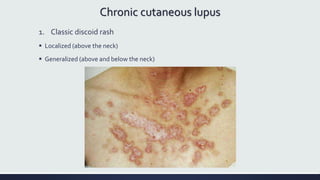

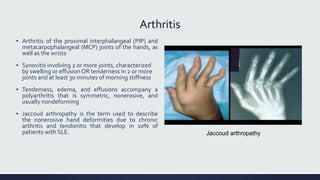

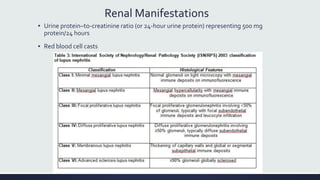

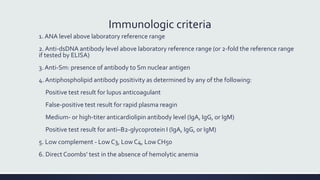

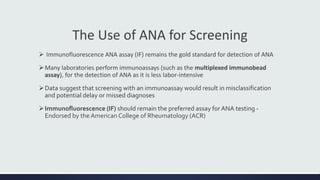

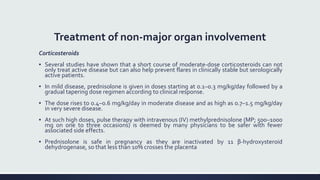

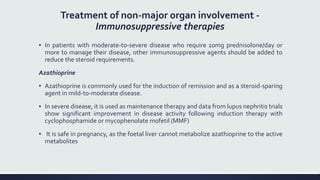

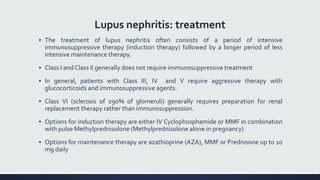

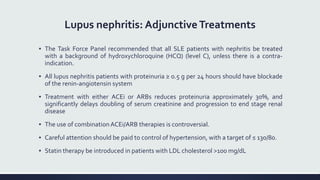

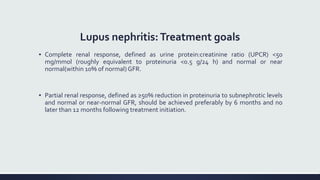

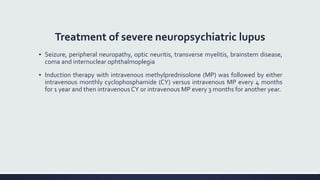

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation in tissues throughout the body. The name comes from a 13th century physician who observed facial lesions resembling a wolf bite. Diagnosis is based on criteria developed by the American College of Rheumatology including malar rash, discoid lesions, arthritis, serositis, renal disease, and immunologic abnormalities. Treatment involves hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants like azathioprine. Lupus nephritis requires aggressive therapy with glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil. Treatment goals are complete or partial renal response through reduction