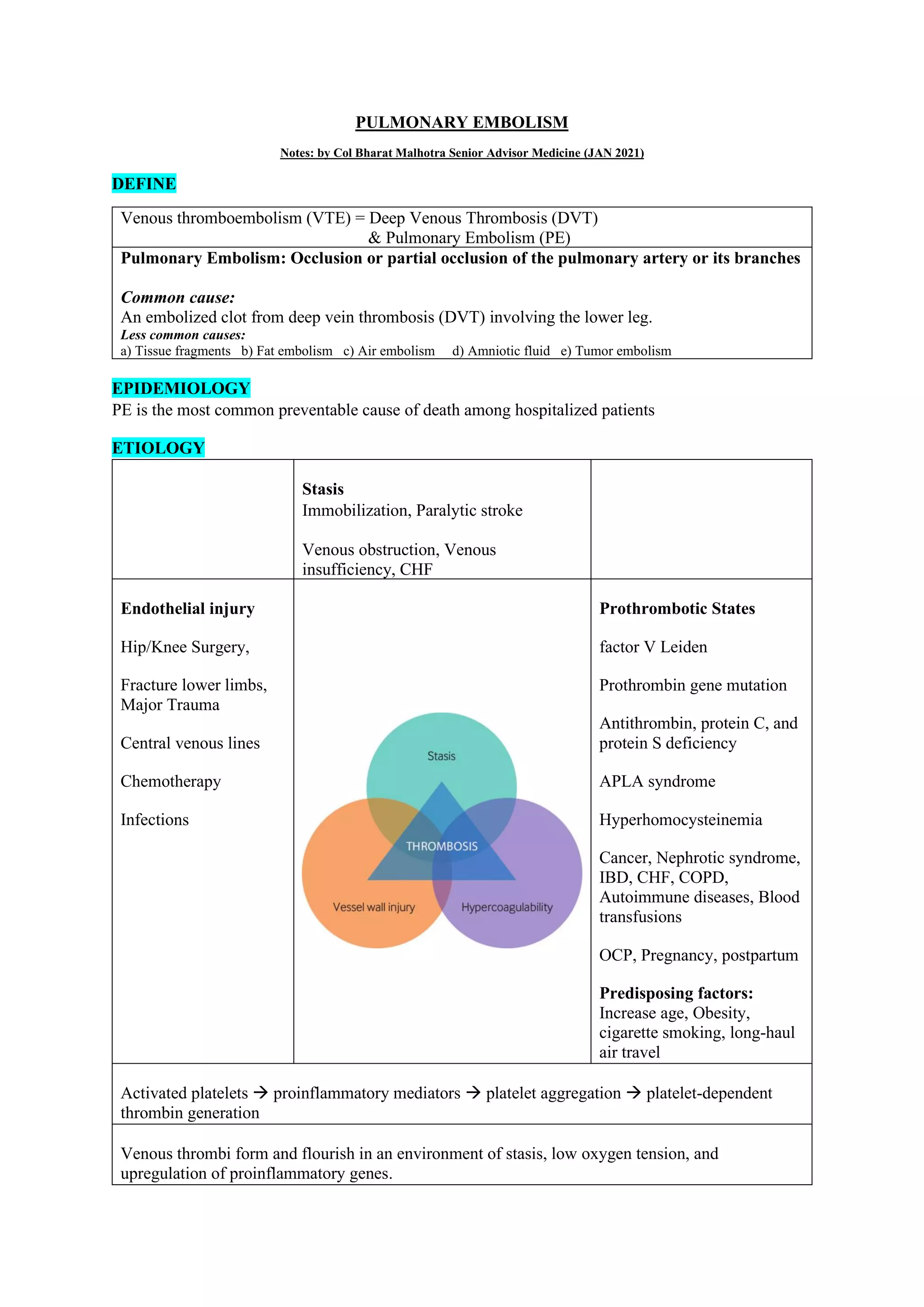

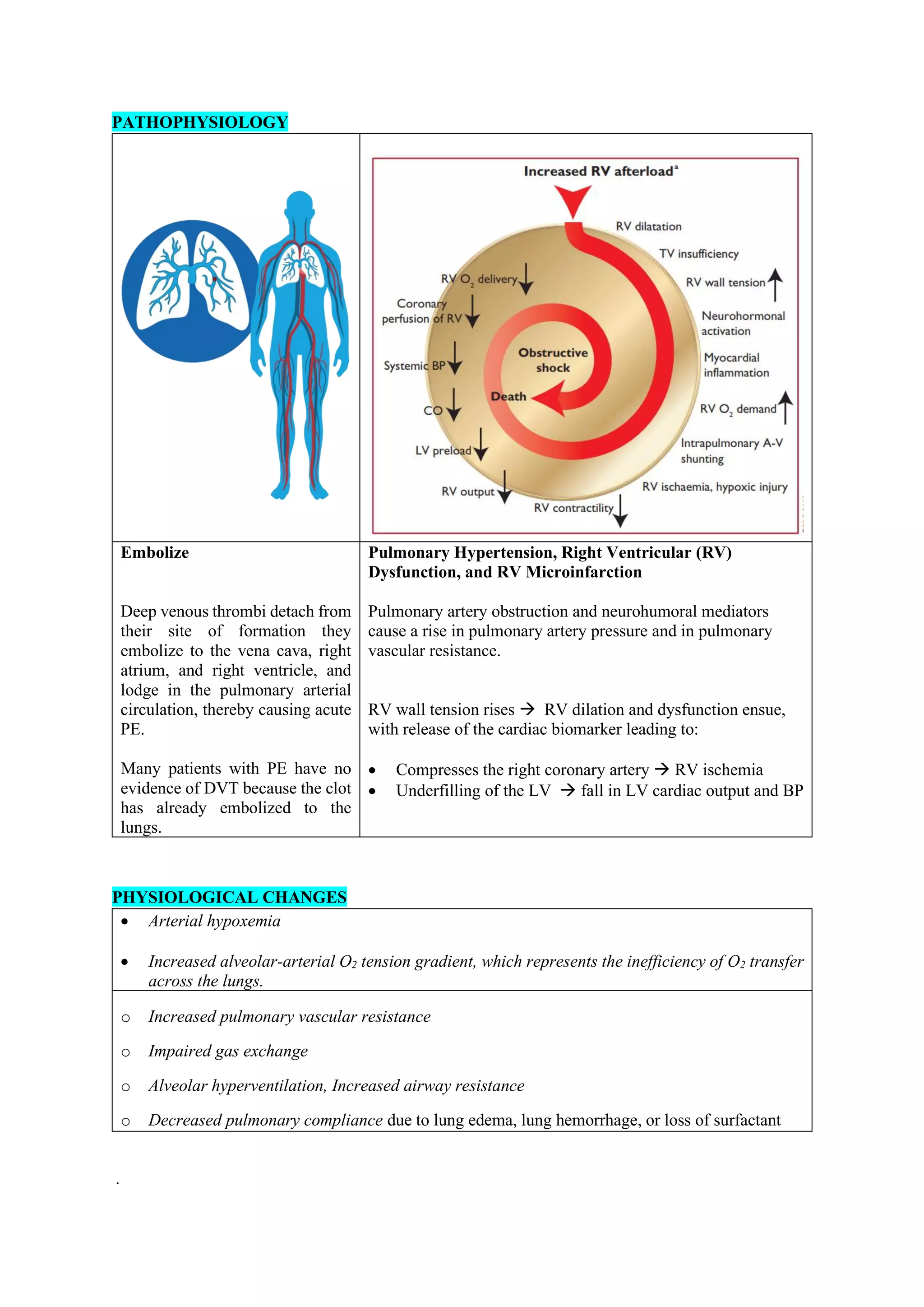

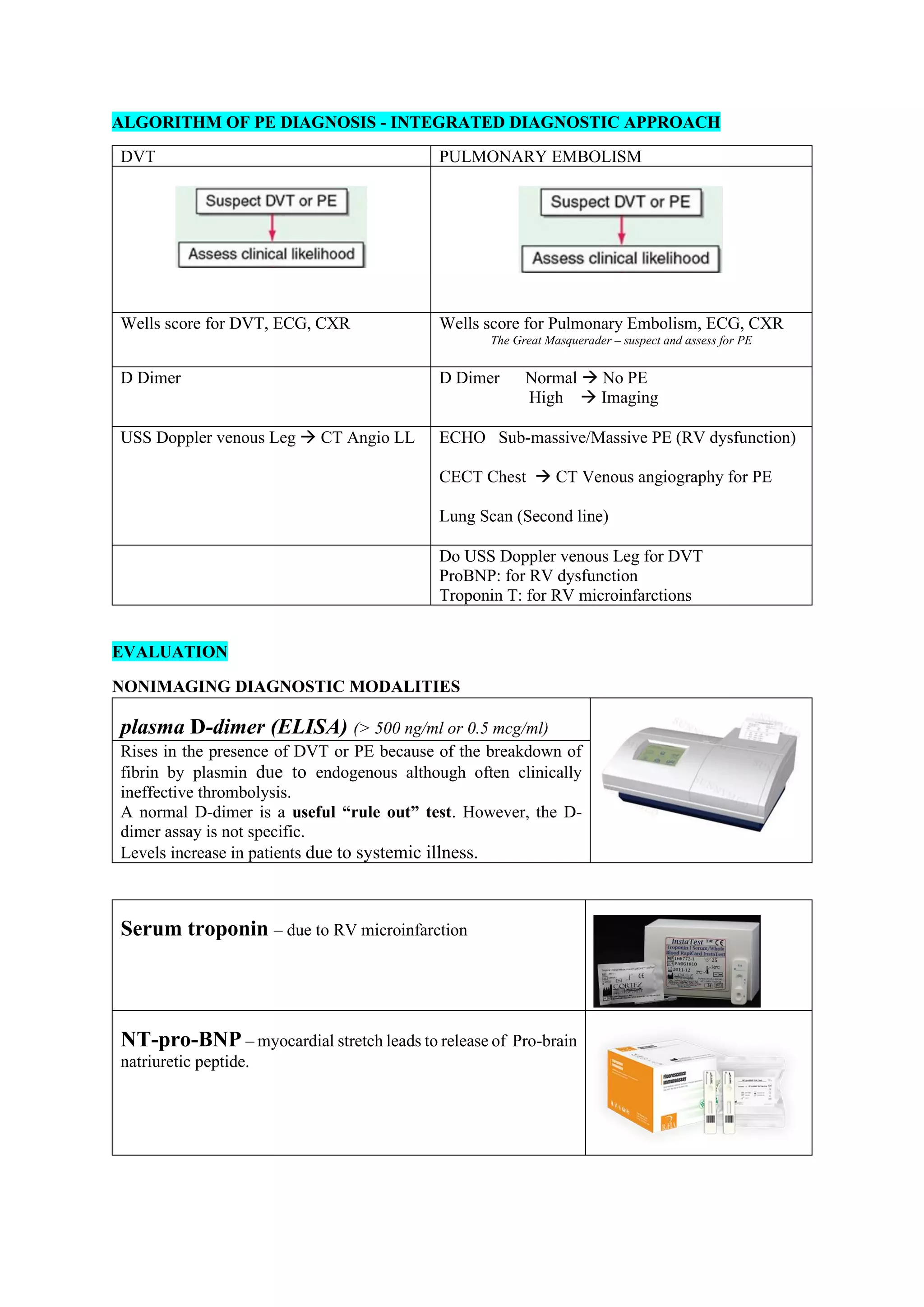

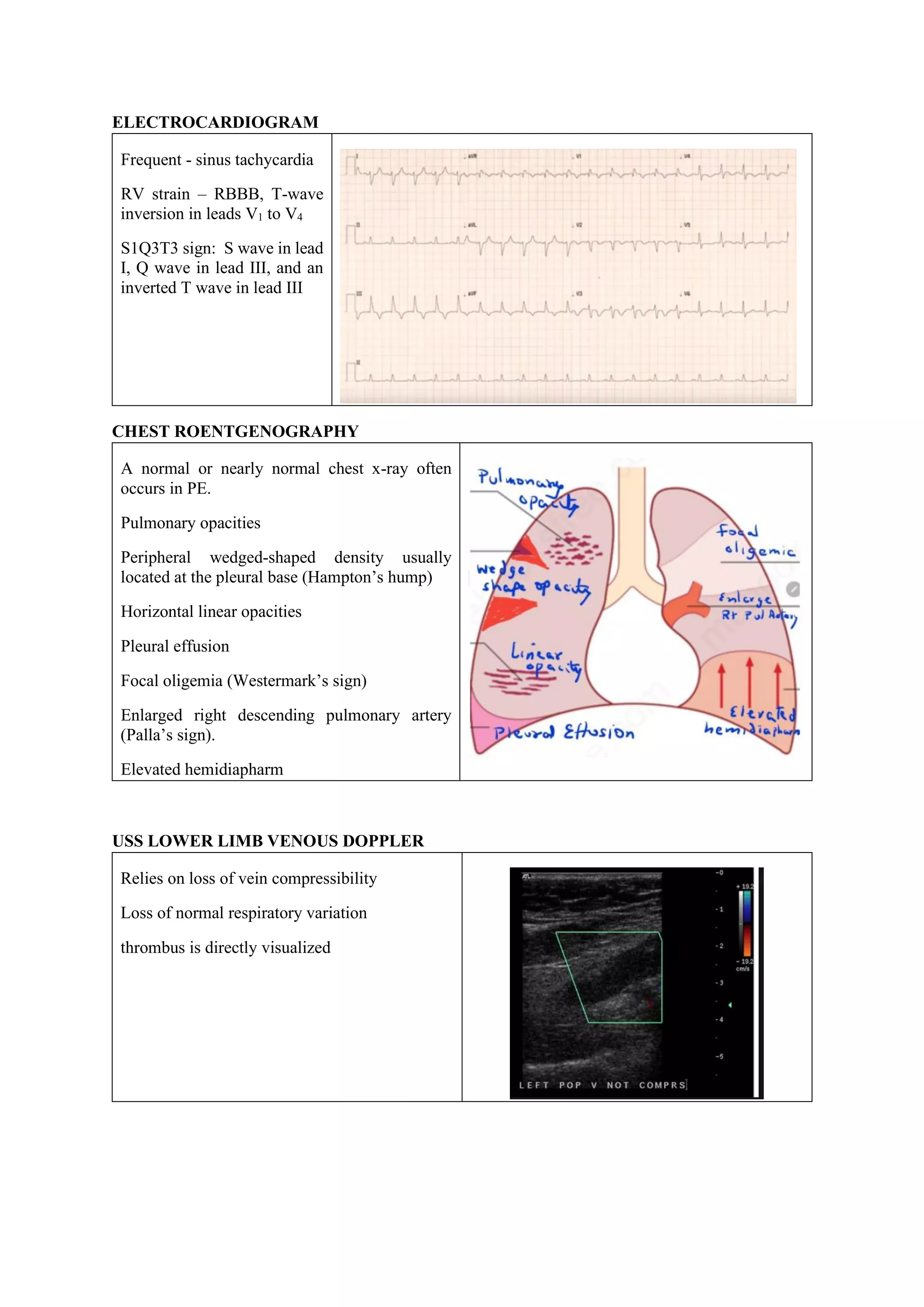

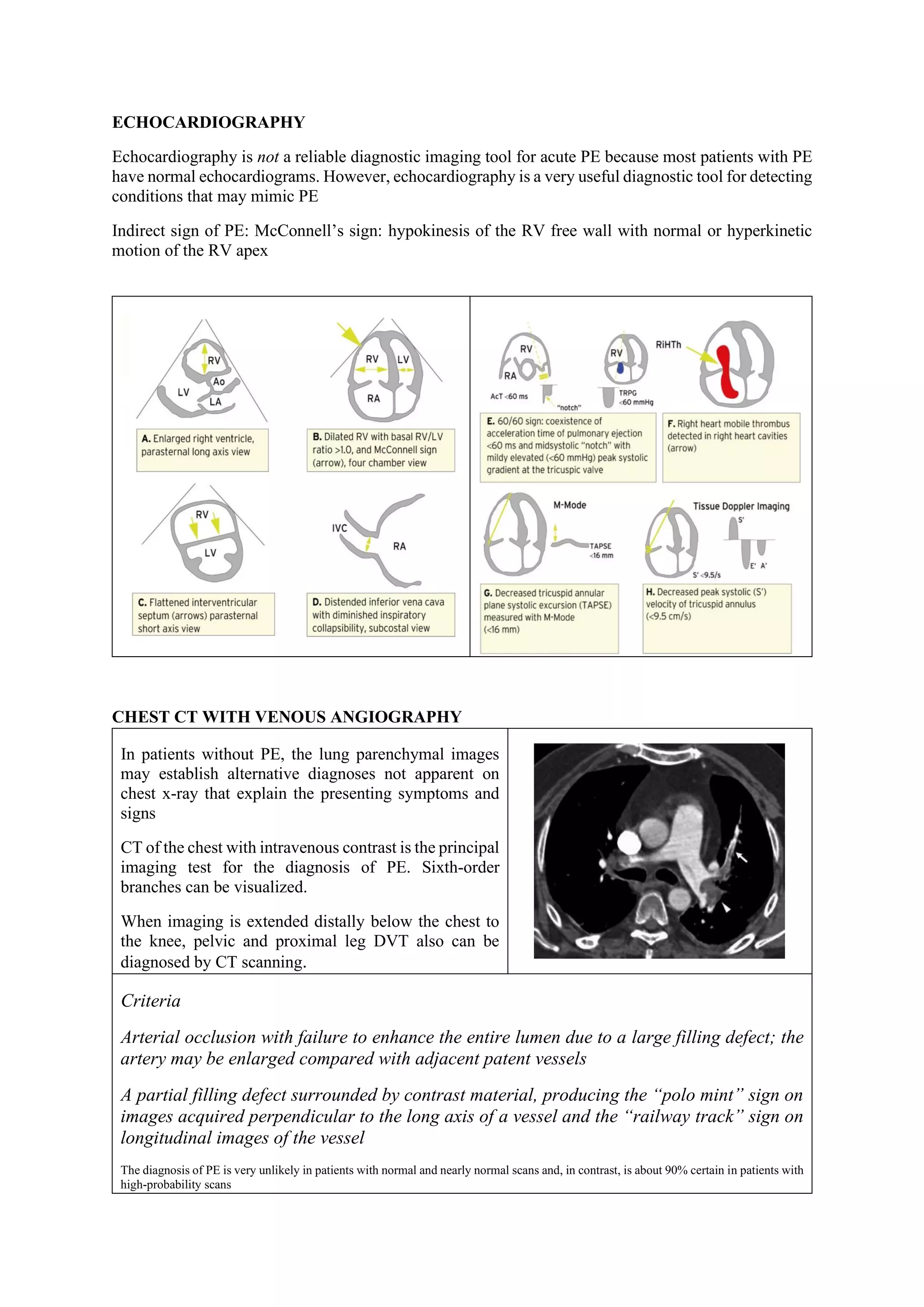

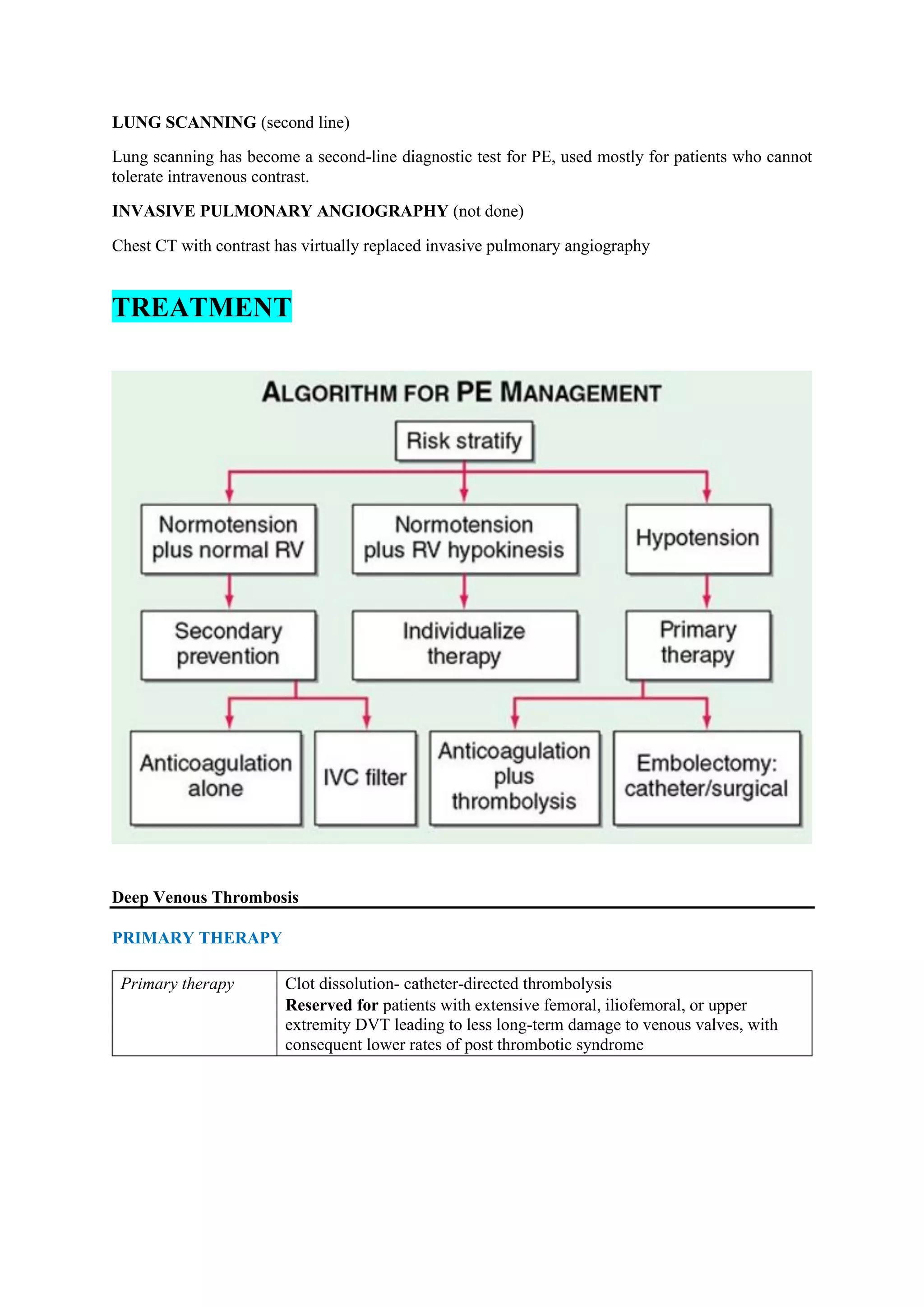

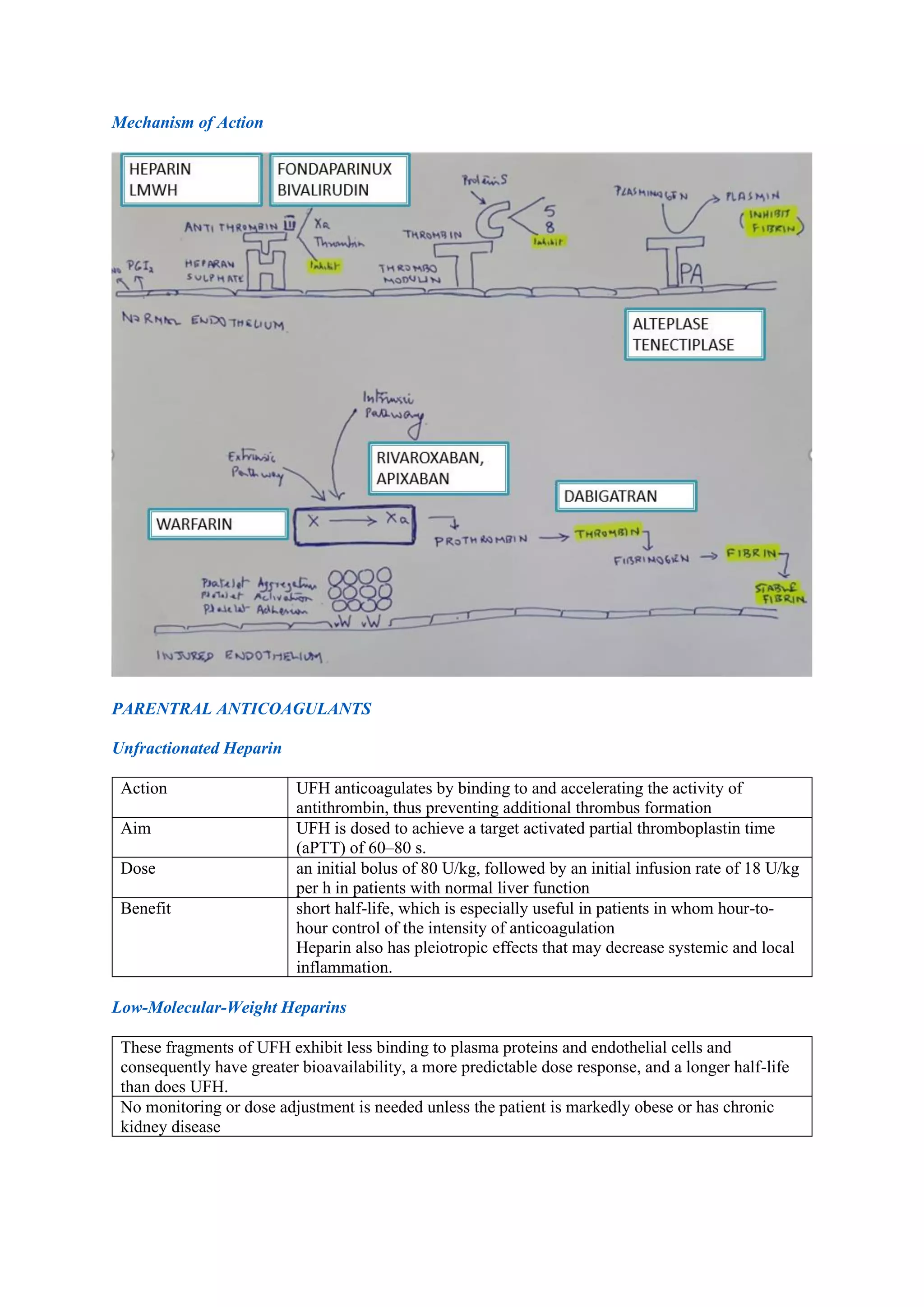

Pulmonary embolism (PE), primarily caused by deep vein thrombosis (DVT), is a serious condition characterized by the blockage of pulmonary arteries, leading to potentially life-threatening complications. The document outlines the causes, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment options for PE and DVT, emphasizing the importance of anticoagulation therapy and risk stratification. Additionally, it discusses various diagnostic modalities and the classification of PE severity, along with detailed treatment regimens for managing DVT and preventing recurrent events.