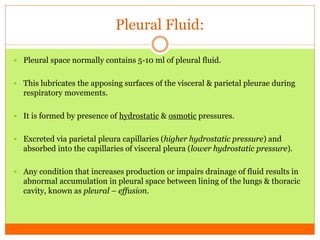

Pleural effusion is the abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, occurring due to various conditions affecting fluid production or drainage. It can be classified as transudative or exudative based on the fluid characteristics and is commonly associated with diseases like pneumonia and heart failure. Diagnosis involves imaging, fluid analysis, and management is focused on treating the underlying cause.