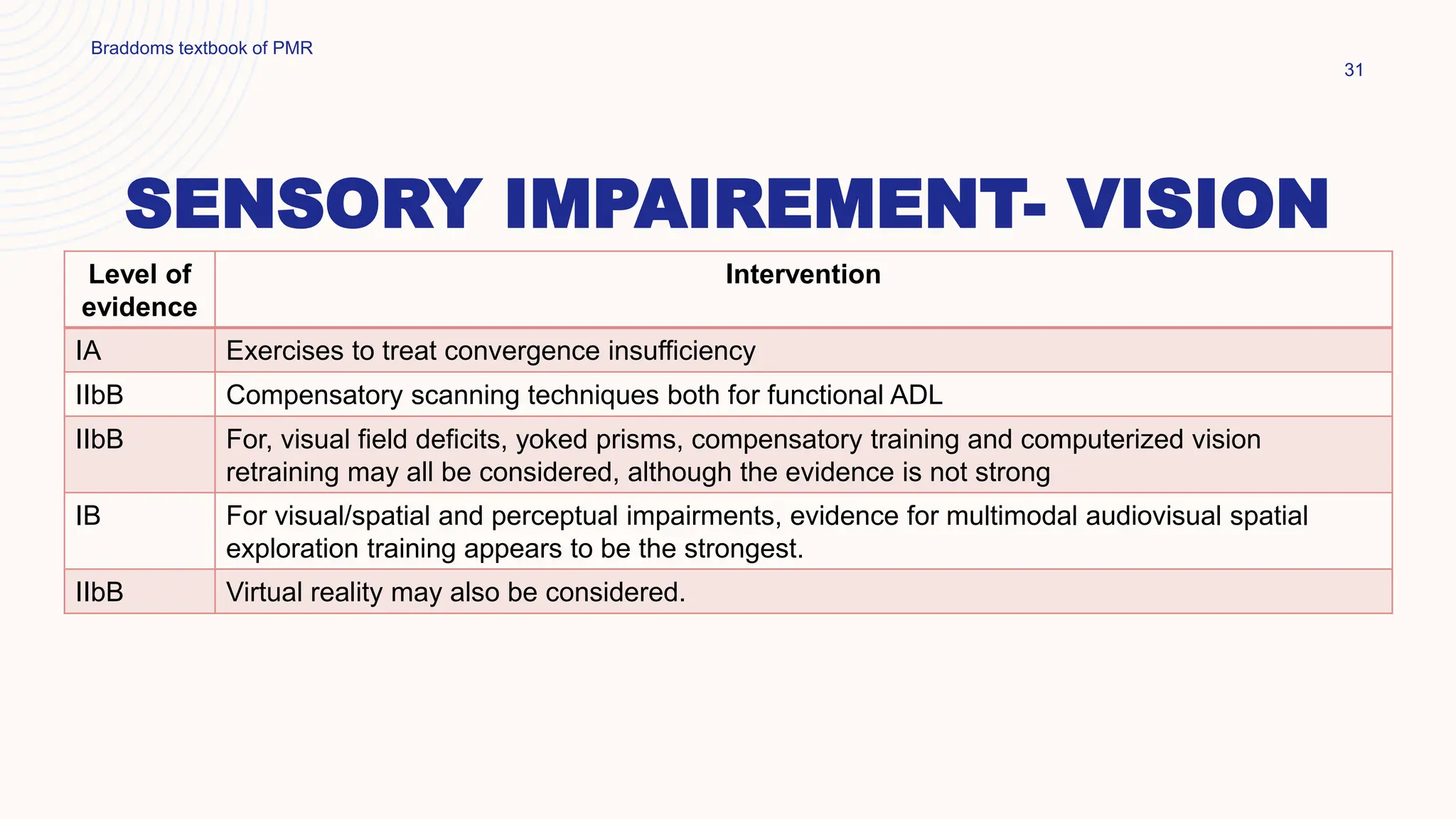

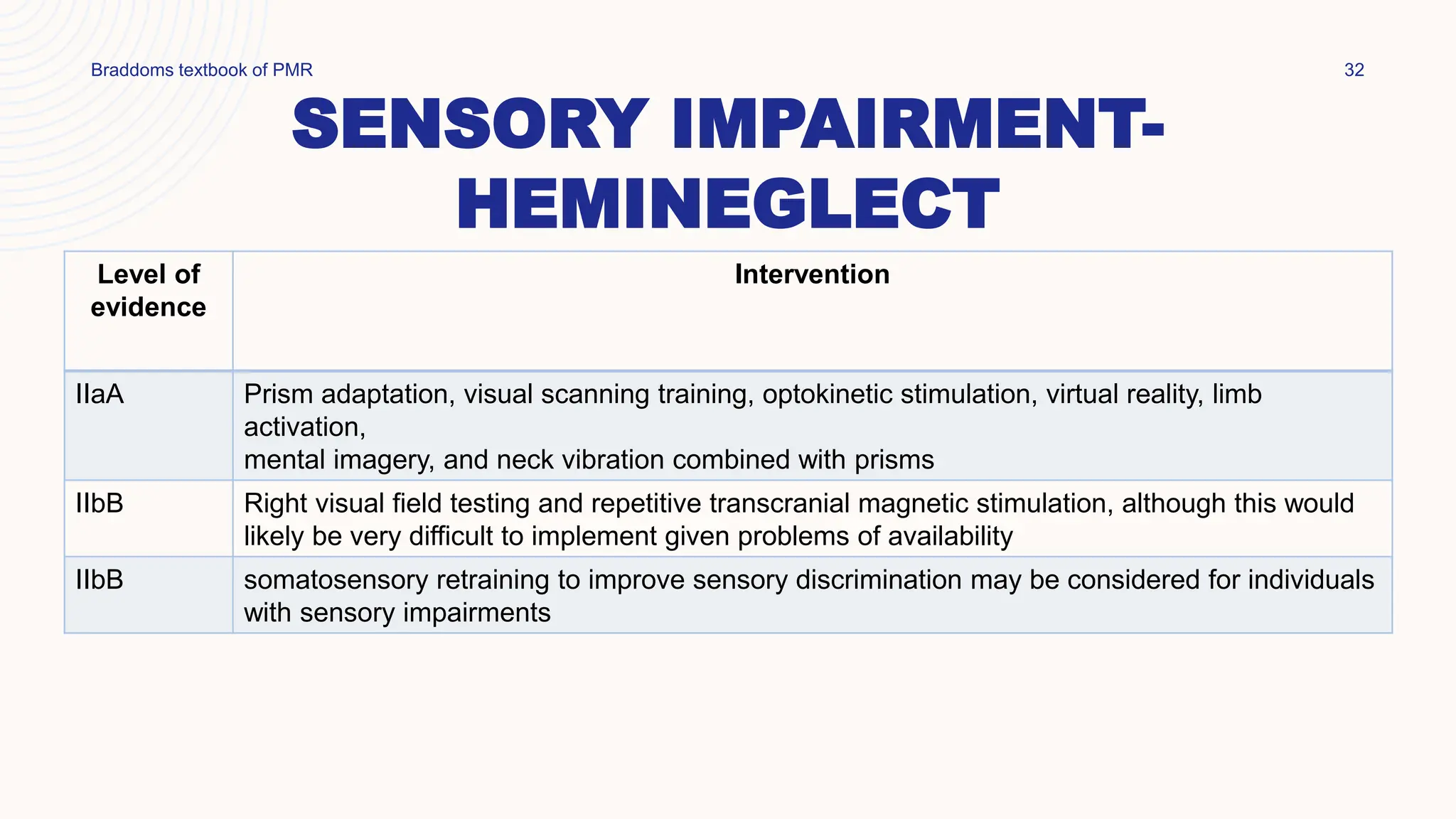

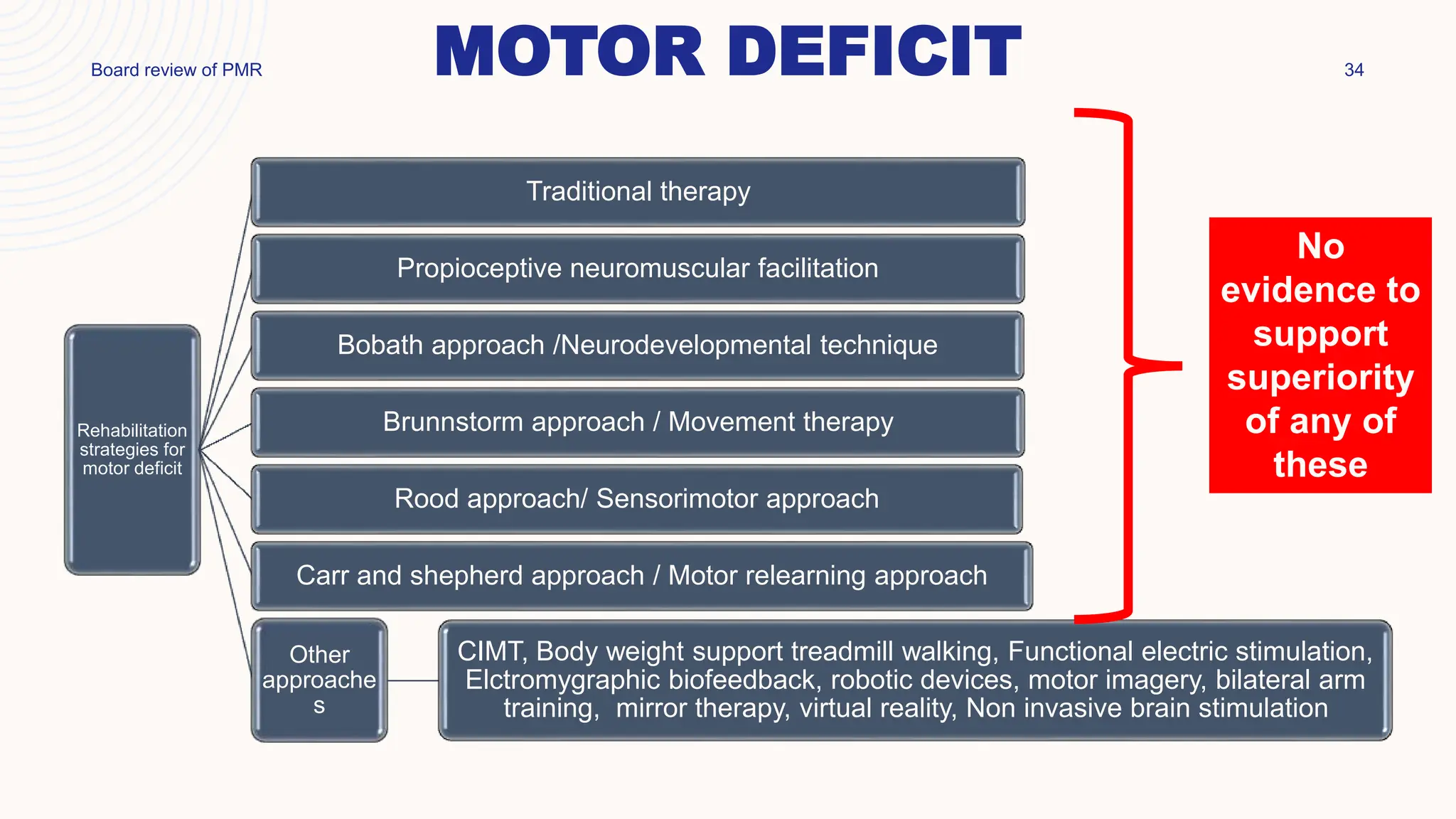

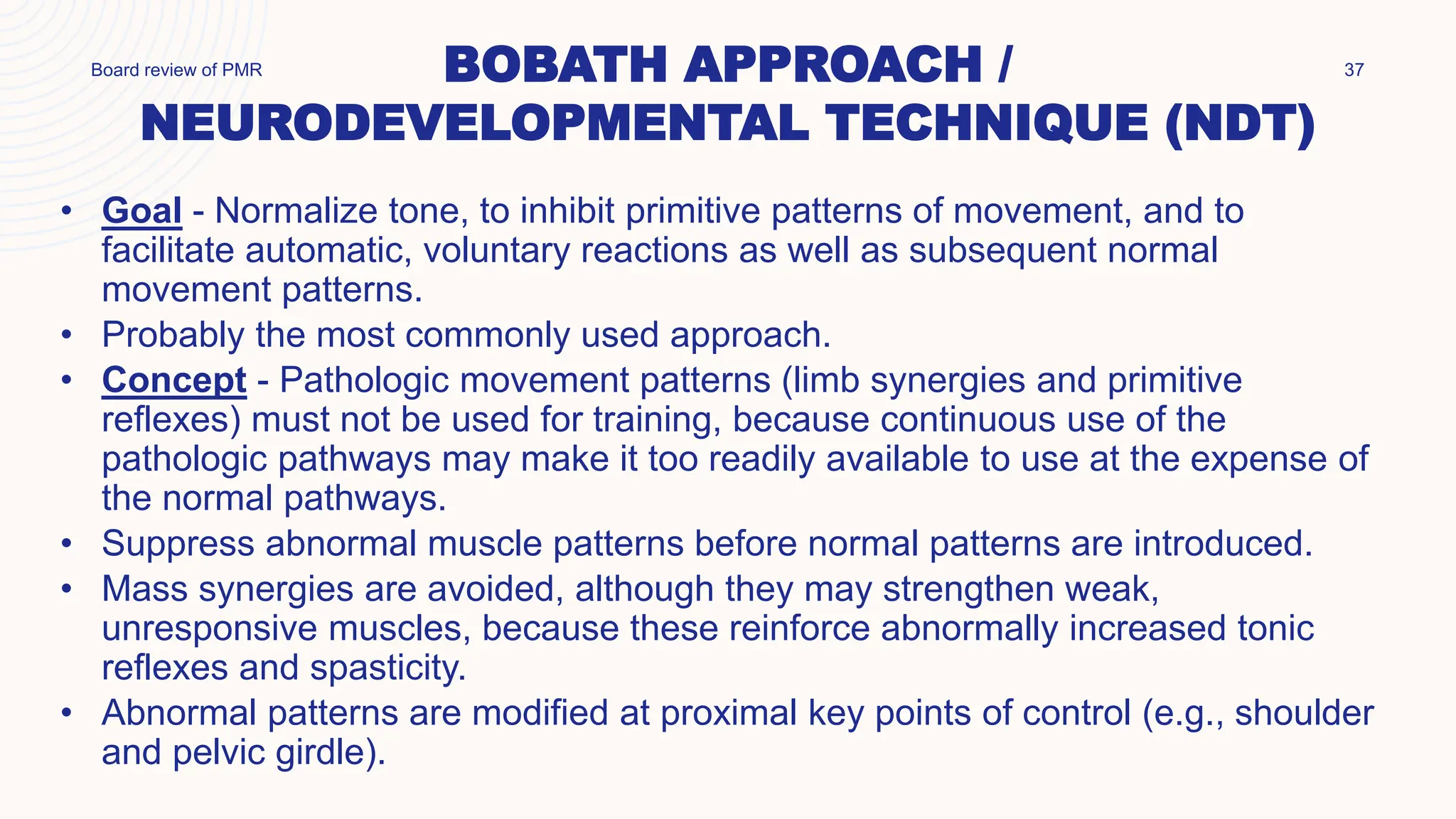

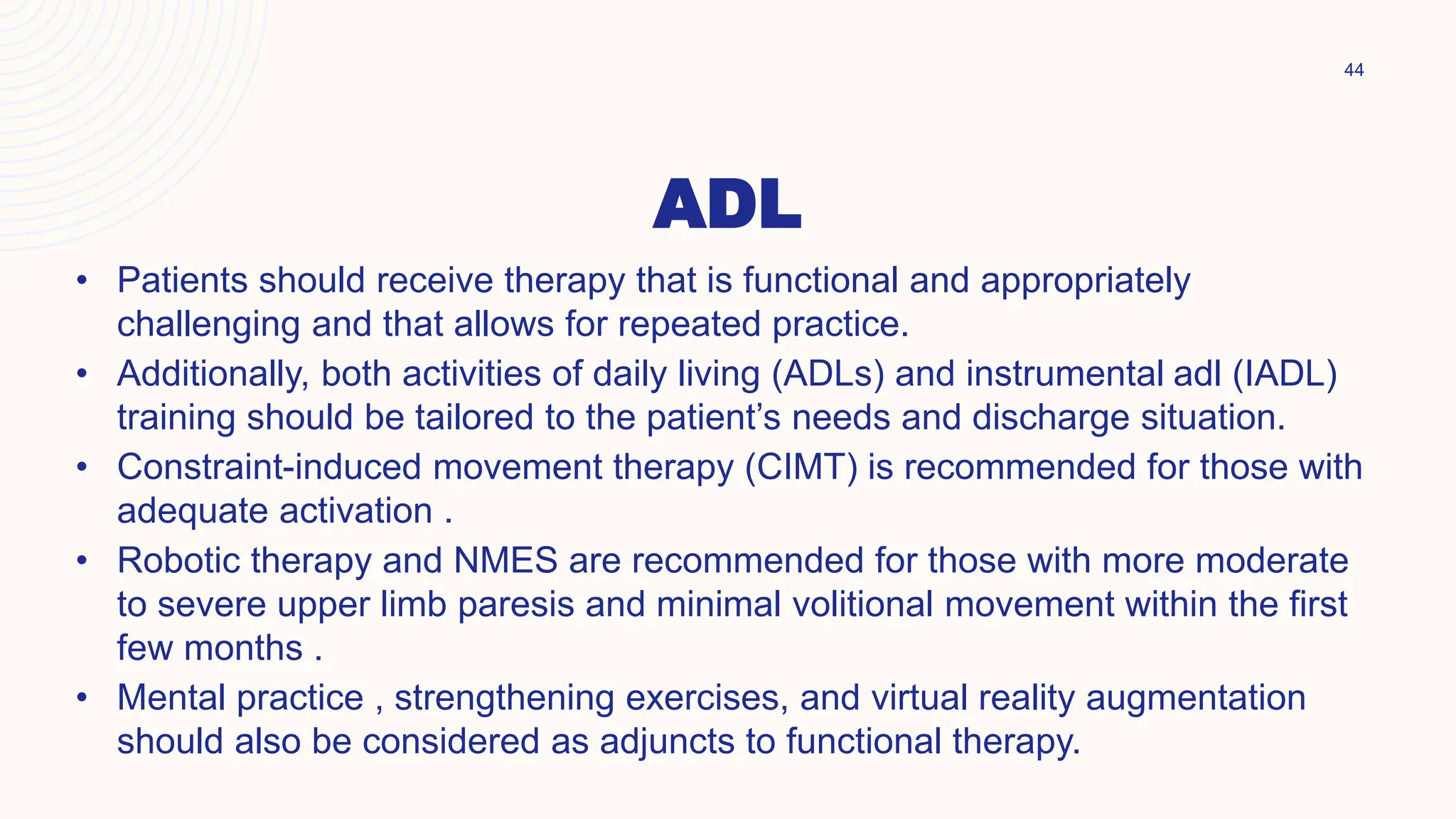

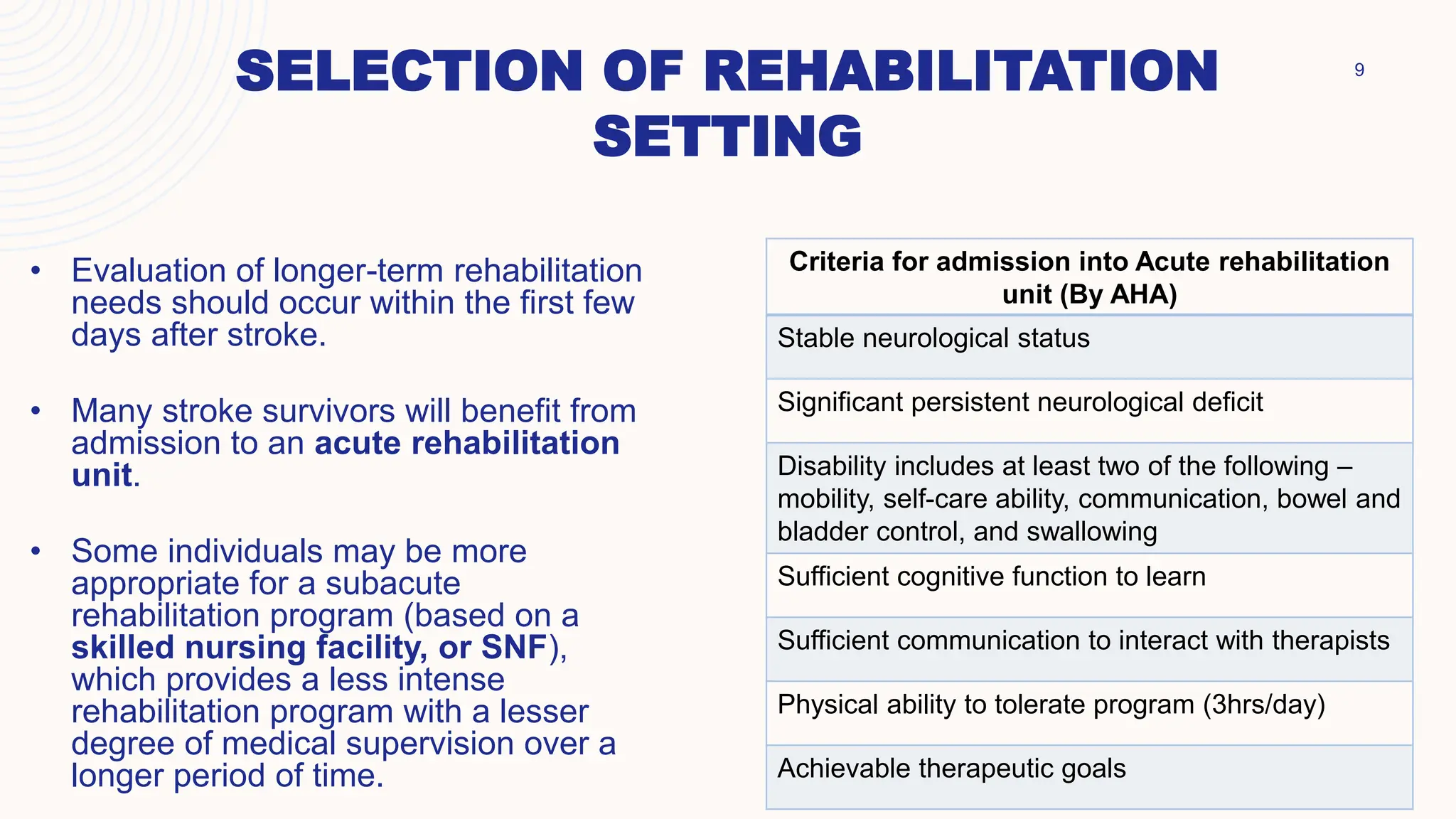

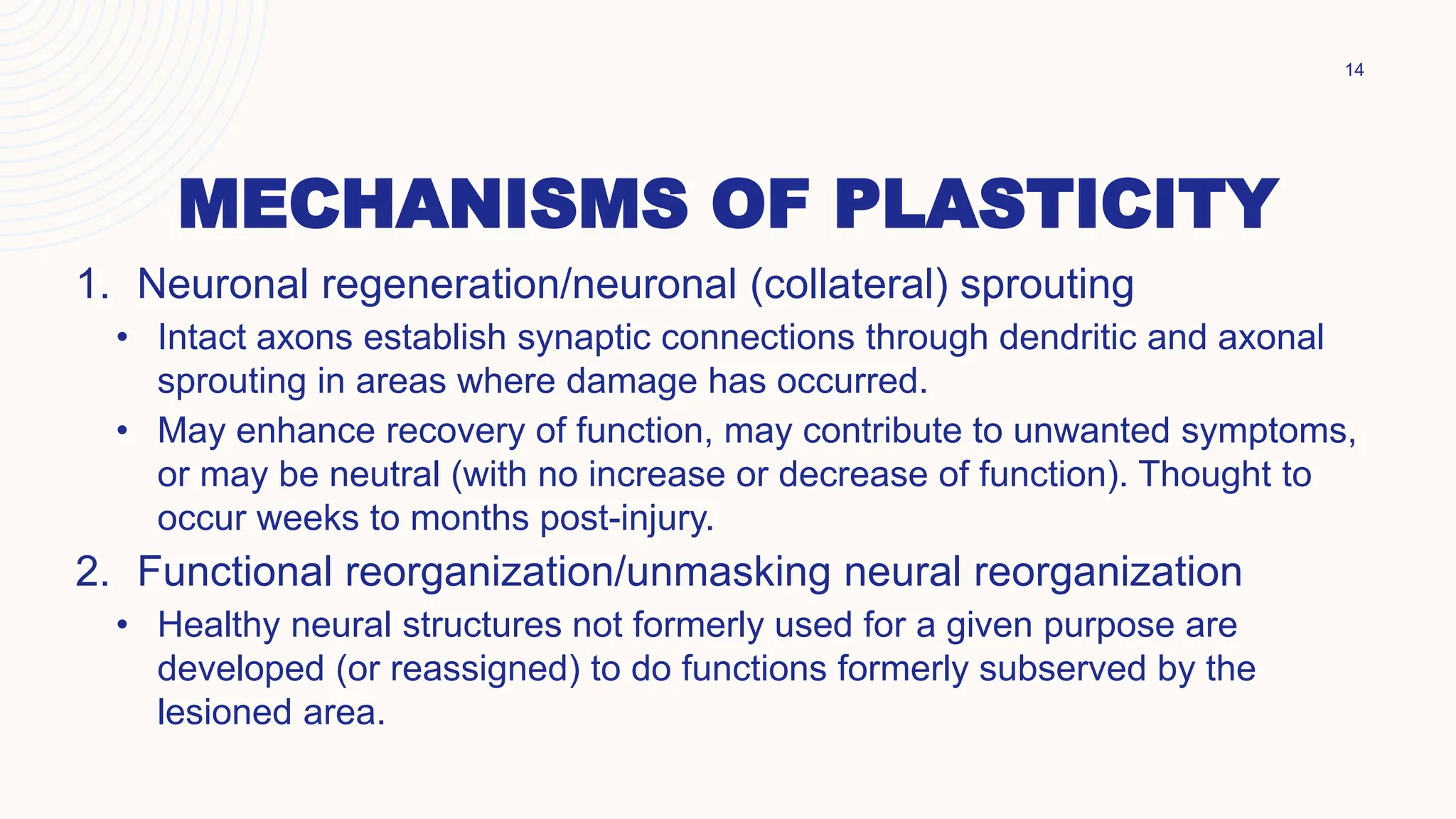

This document provides an overview of stroke rehabilitation. It discusses definitions of stroke and outlines rehabilitation measures in the acute phase, including prevention of complications like skin breakdown, aspiration, contractures, and deep vein thrombosis. It also covers selection of rehabilitation settings, the neurophysiology of recovery including cortical reorganization, and assessment of functional ability. Rehabilitation approaches for specific impairments are outlined, like cognition, aphasia, dysphagia, sensory problems, and motor deficits. Traditional therapies as well as newer approaches like constraint-induced movement therapy are mentioned.

![] 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strokerehabilitation-231009065819-29020af3/75/Stroke-rehabilitation-27-2048.jpg)