This document outlines an optics switching technology course, including:

- The course covers switching technology, including understanding switching systems, fabrics, implementations, and optical switching.

- The schedule lists 13 lectures and 7 exercises over 14 weeks, covering topics such as switch fabrics, PDH, ATM, and optical networks.

- Readings are provided to supplement the lecture materials, and requirements include exercises, a grading system, and a final examination.

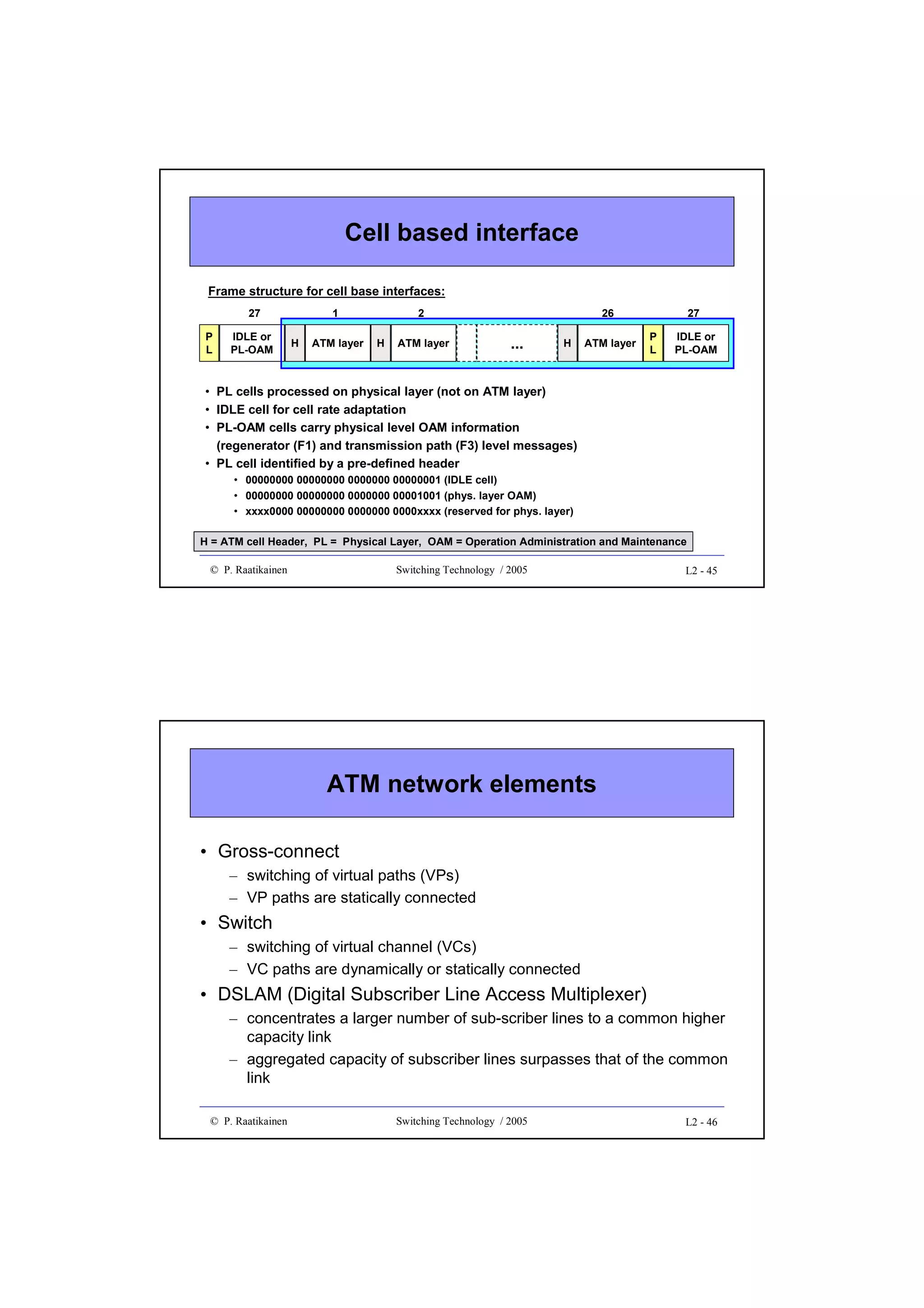

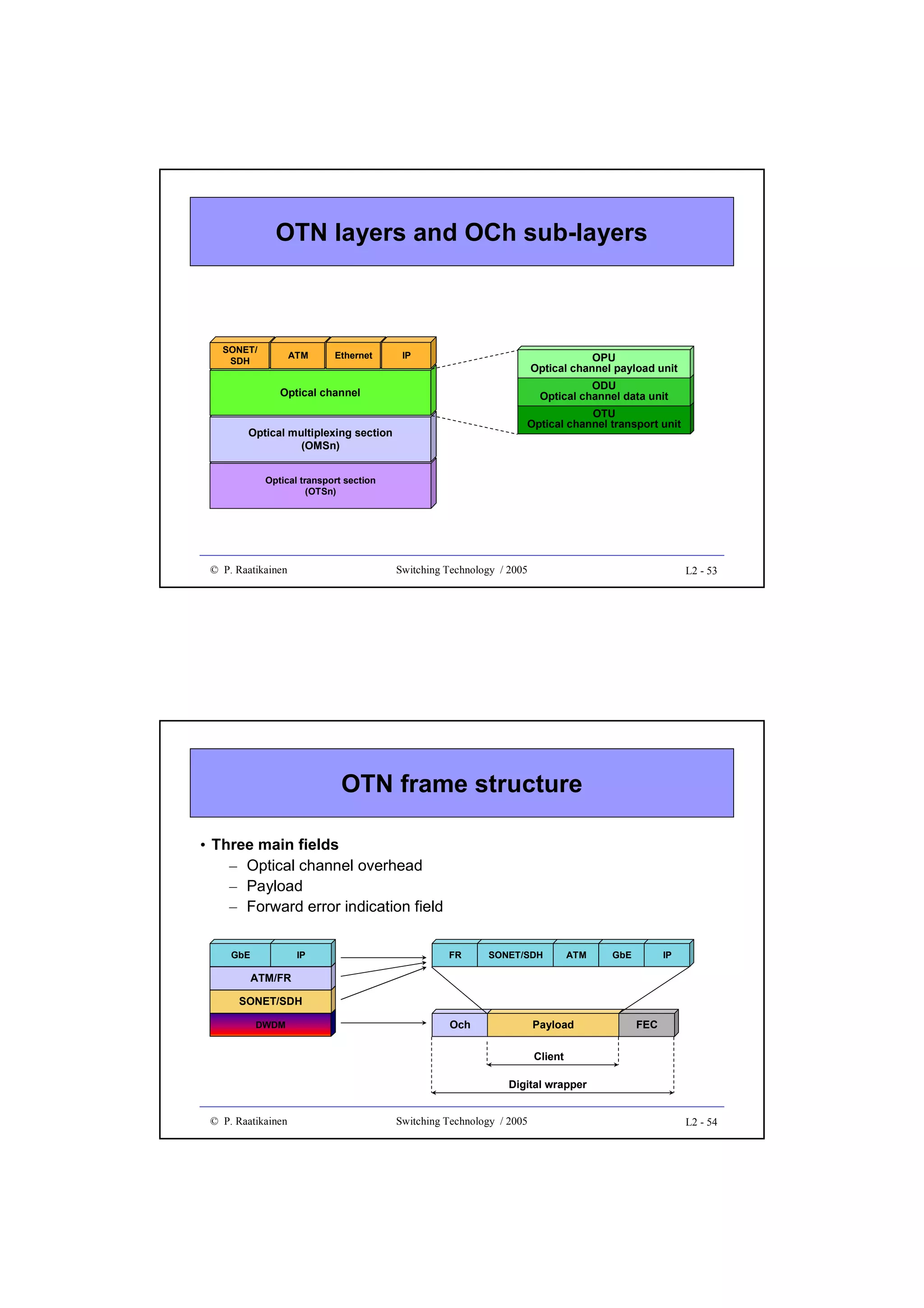

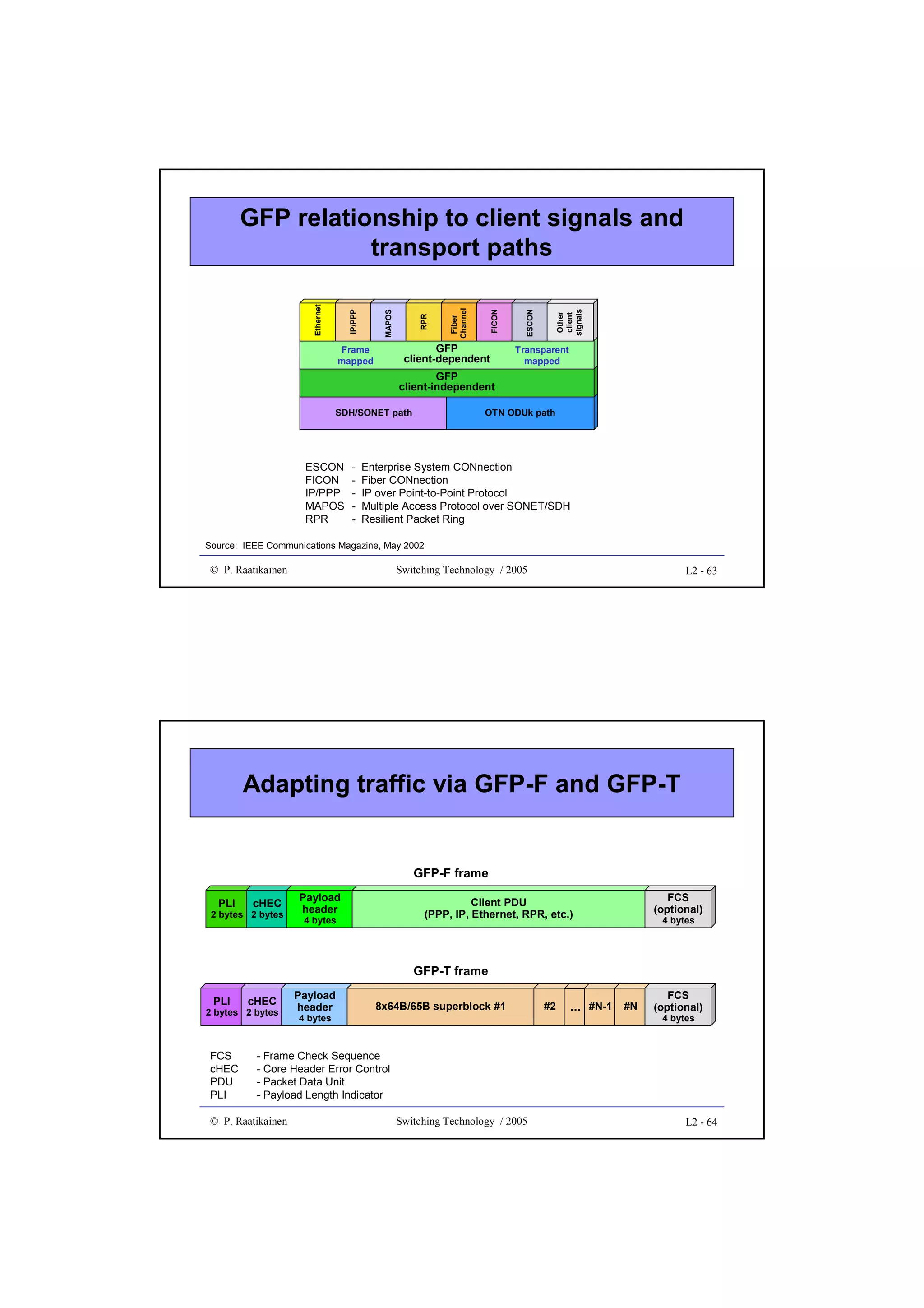

![GFP client data frame

• Composed of a frame header and payload

• Core header intended for data link management

– payload length indicator (PLI, 2 octets), HEC (CRC-16, 2 octets)

• Payload field divided into payload header, payload and optional FCS

(CRC-32) sub-fields

• Payload header includes:

– payload type (2 octets) and type HEC (2 octets) sub-fields

– optional 0 - 60 octets of extension header

• Payload:

– variable length (0 - 65 535 octets, including payload header and FCS) for

frame mapping mode (GFP-F) - frame multiplexing

– fixed size Nx[536, 520] for transparent mapping mode (GFP-T) - no frame

multiplexing

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2005

L2 - 61

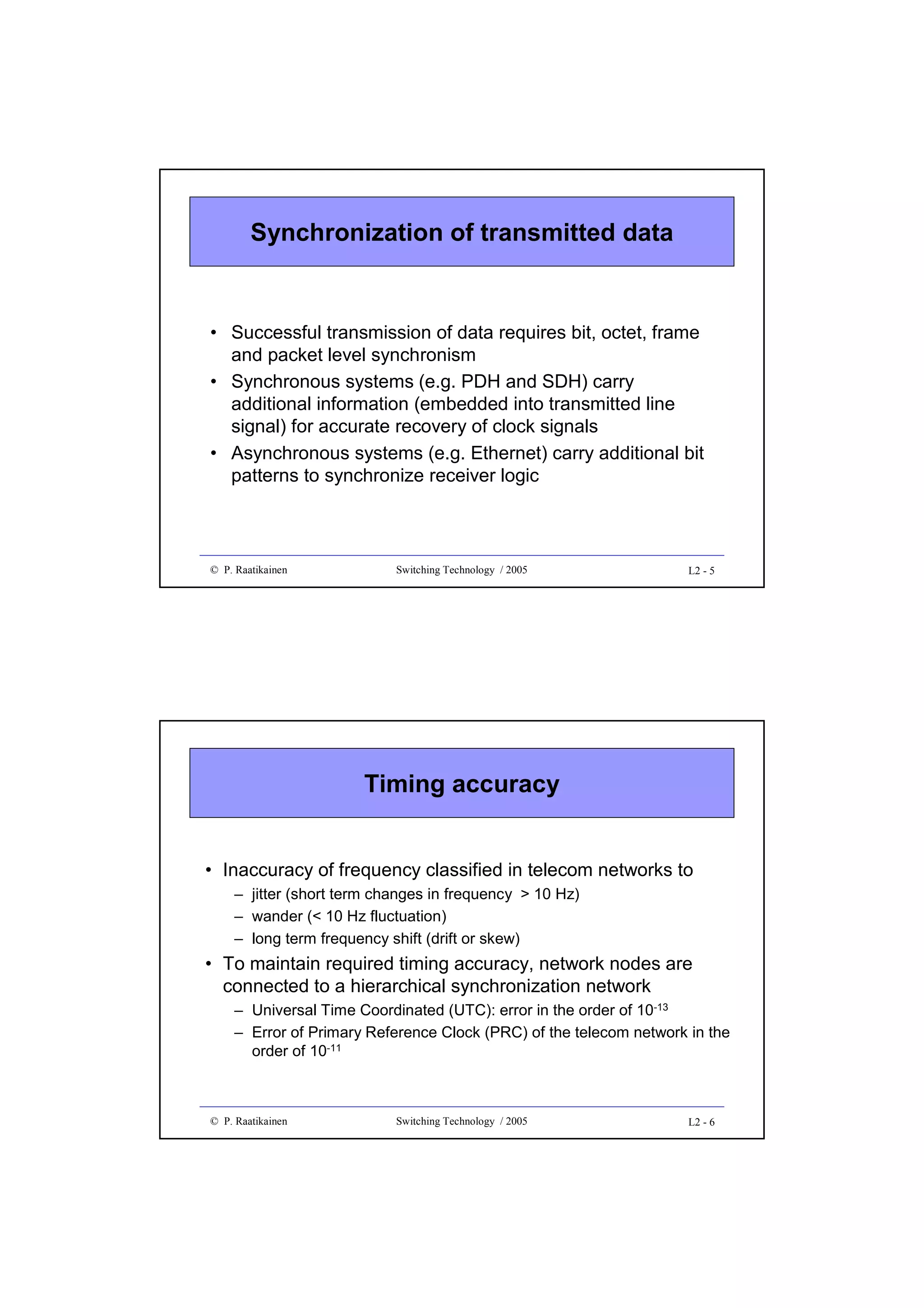

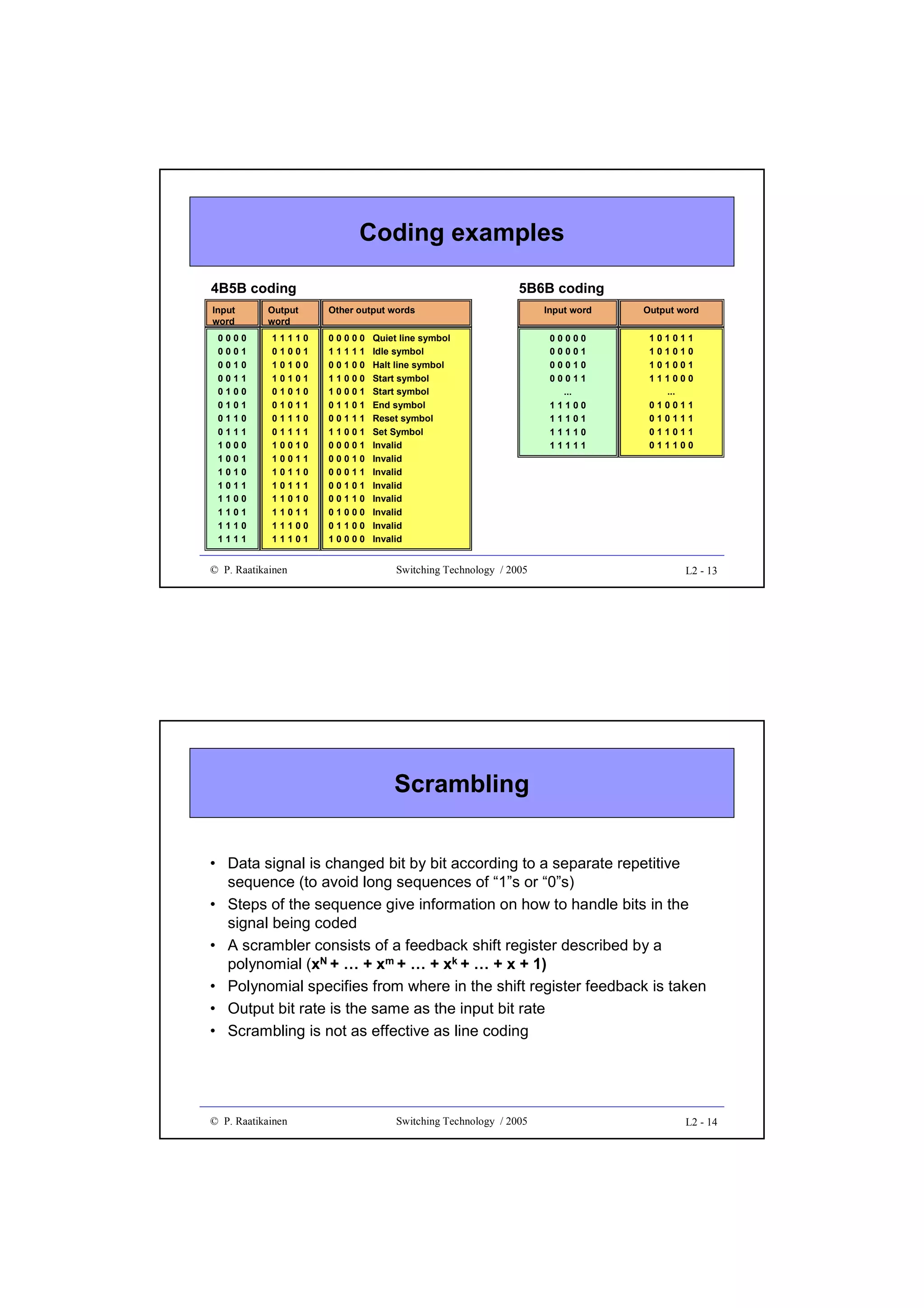

GFP frame structure

Payload length indicator

Core

header

Core HEC

PFI

EXI

UPI

Type HEC

CID

Payload header

Payload

area

PTI

Payload type

0 – 60 bytes

extension header

(optional)

Spare

Extension HEC MSB

Extension HEC LSB

Payload

[N x 536, 520 bytes

or variable length

packet]

Payload FCS

CID - Channel identifier

FCS - Frame Check Sequence

EXI - Extension Header Identifier

HEC - Header Error Check

PFI - Payload FCS Indicator

PTI - Payload Type Indicator

UPI - User payload Identifier

Source: IEEE Communications Magazine, May 2002

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2005

L2 - 62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-57-2048.jpg)

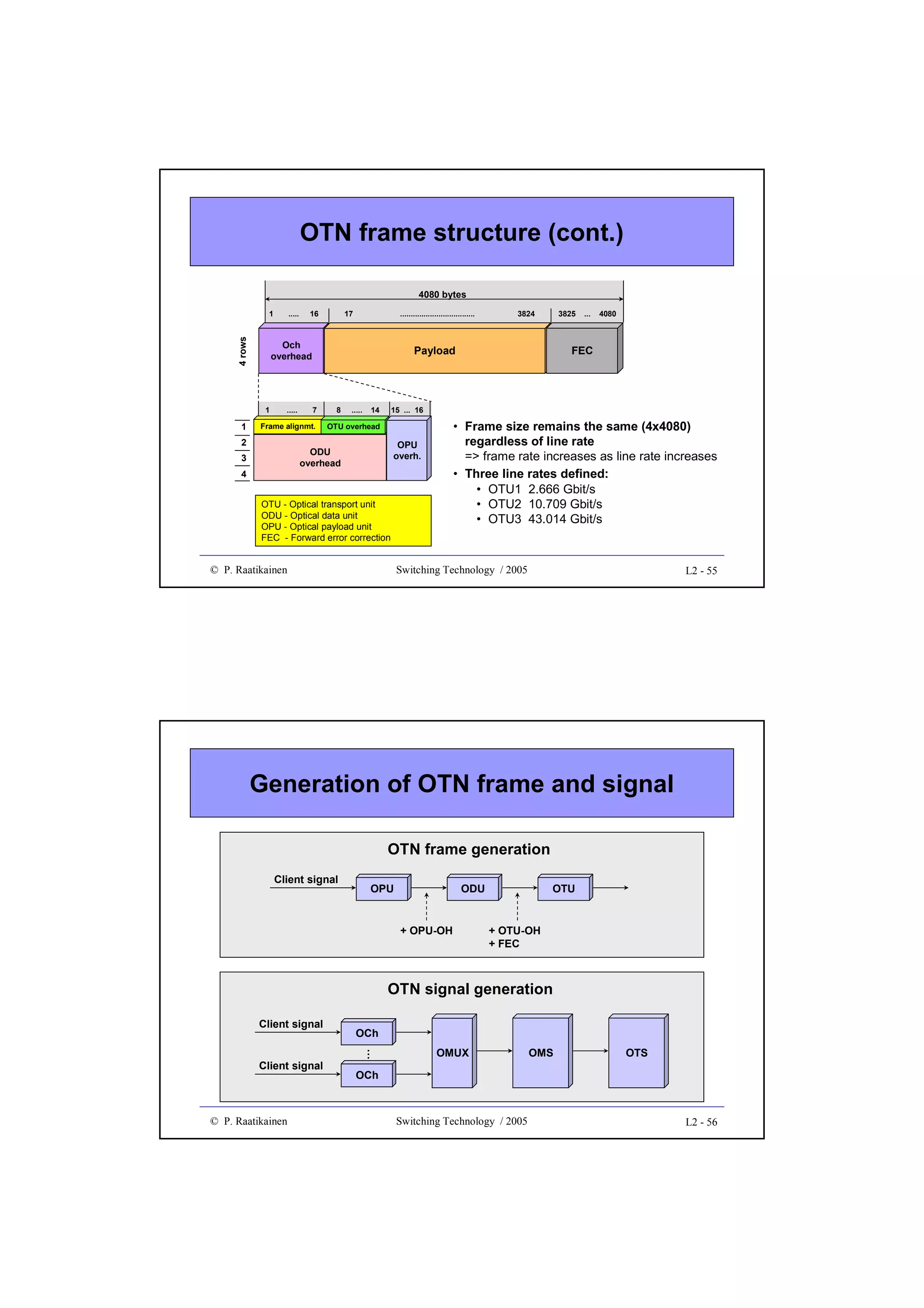

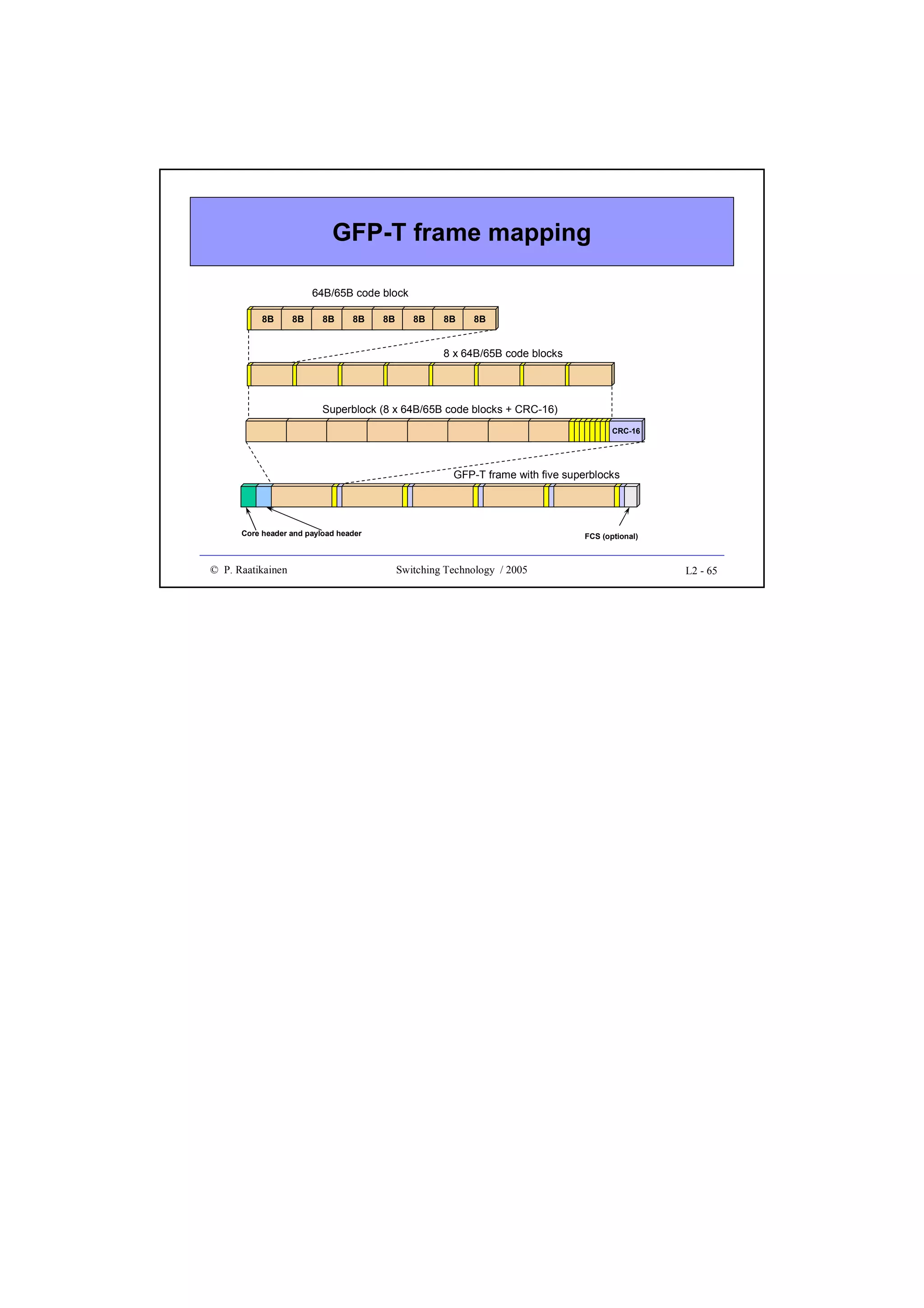

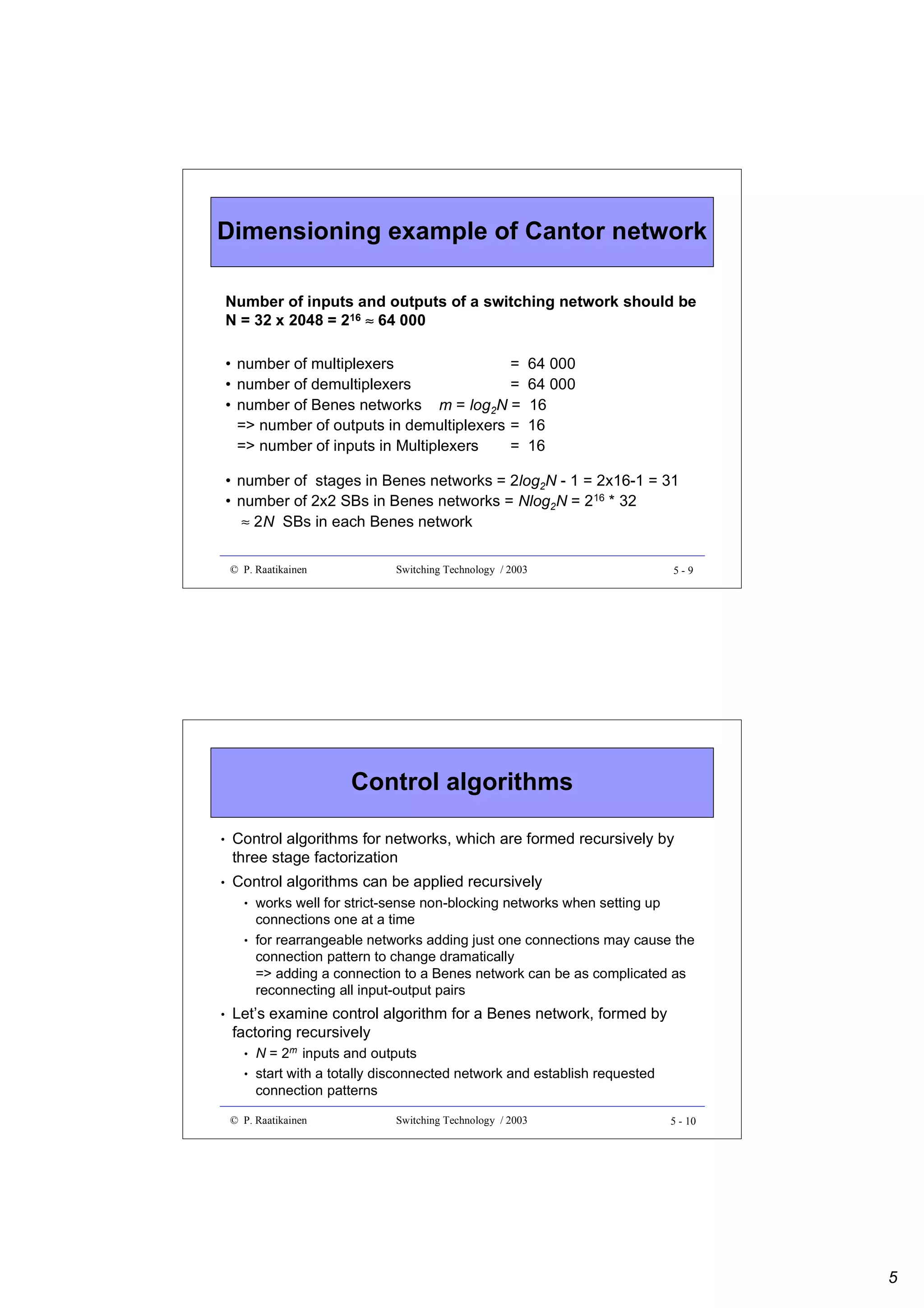

![Throughput

• Throughput gives forwarding/switching speed/efficiency of a

switch fabric

• It is measured in bits/s, octets/s, cells/s, packet/s, etc.

• Quite often throughput is given in the range (0 ... 1.0], i.e. the

obtained forwarding speed is normalized to the theoretical

maximum throughput

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

3 - 11

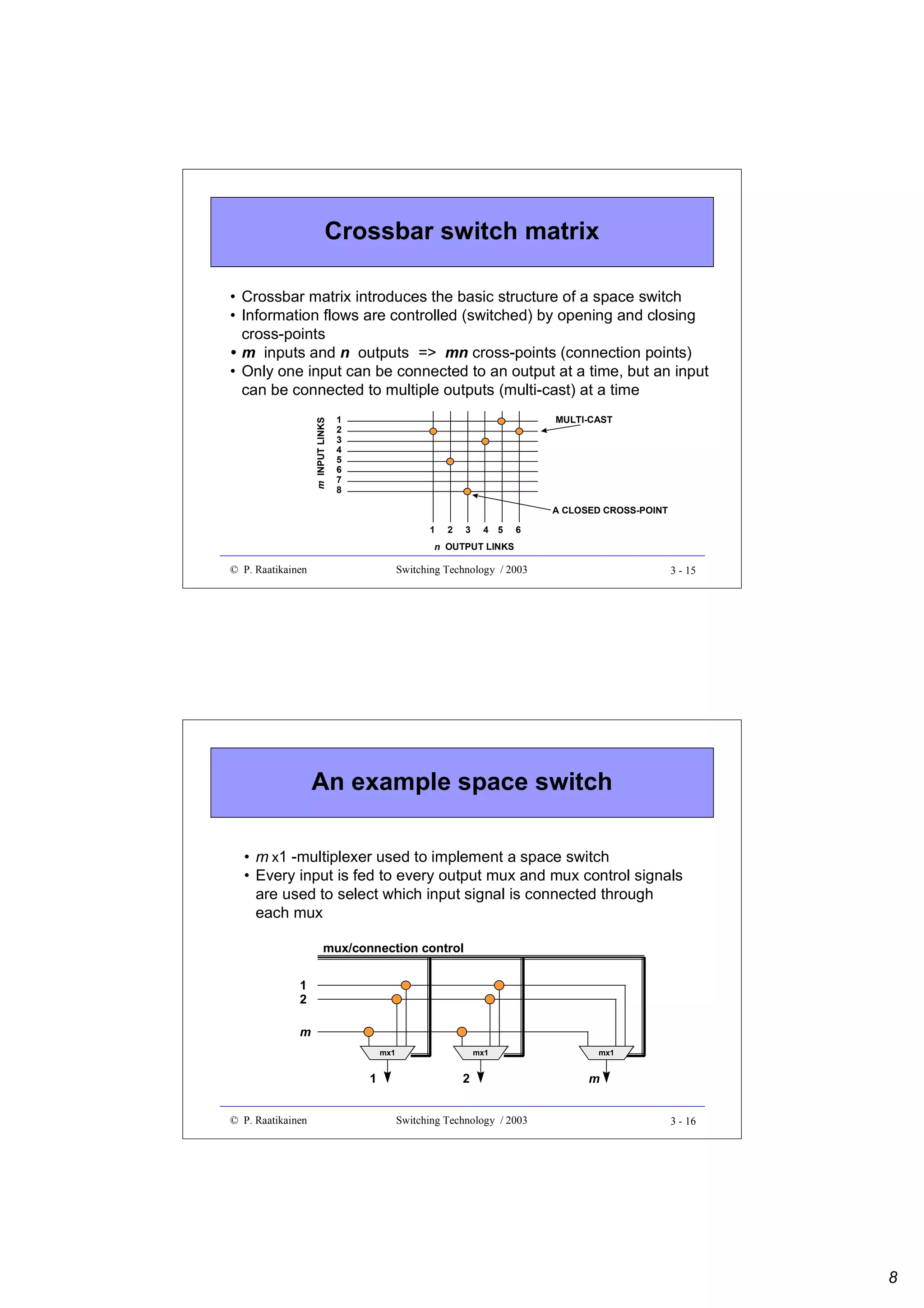

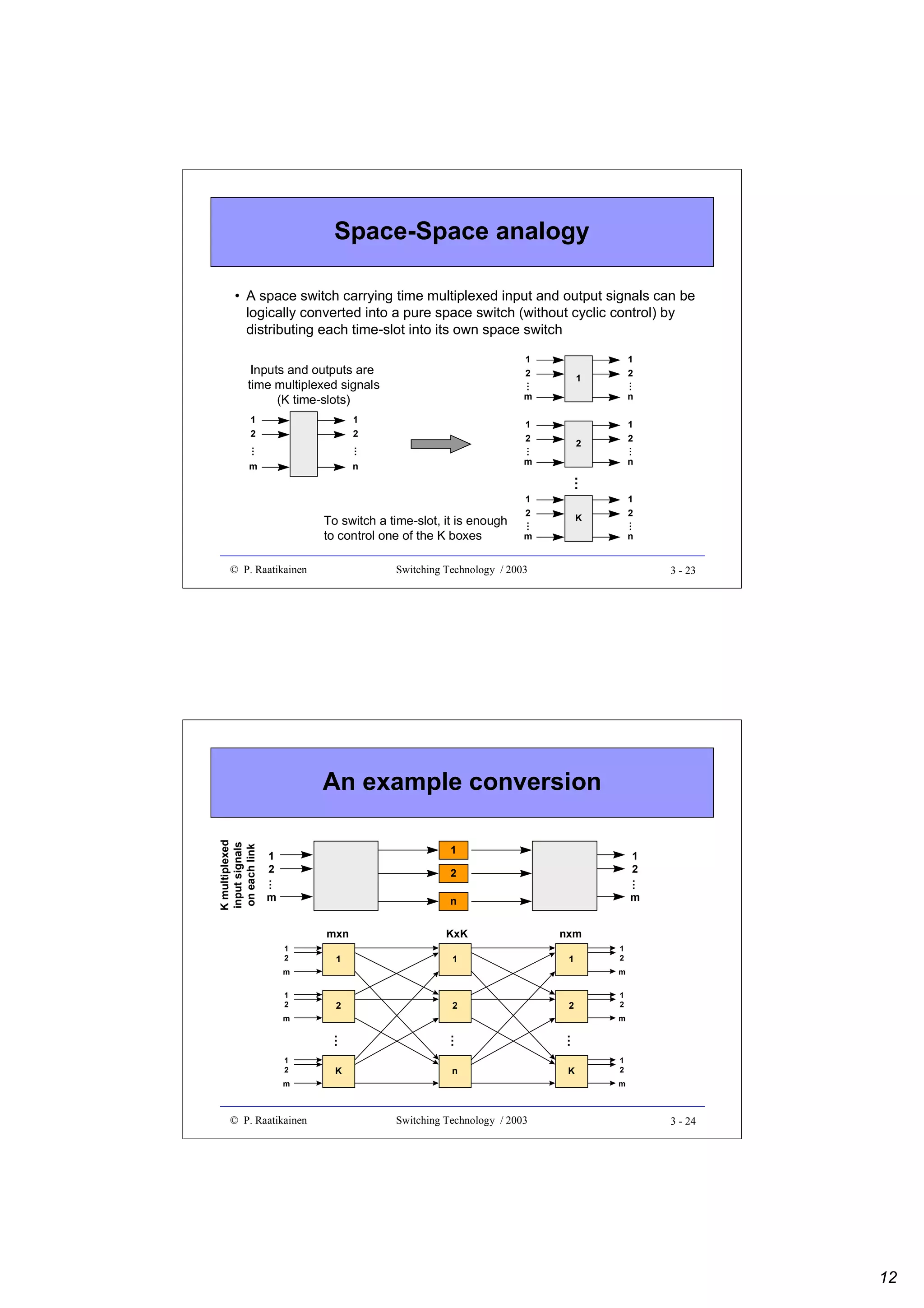

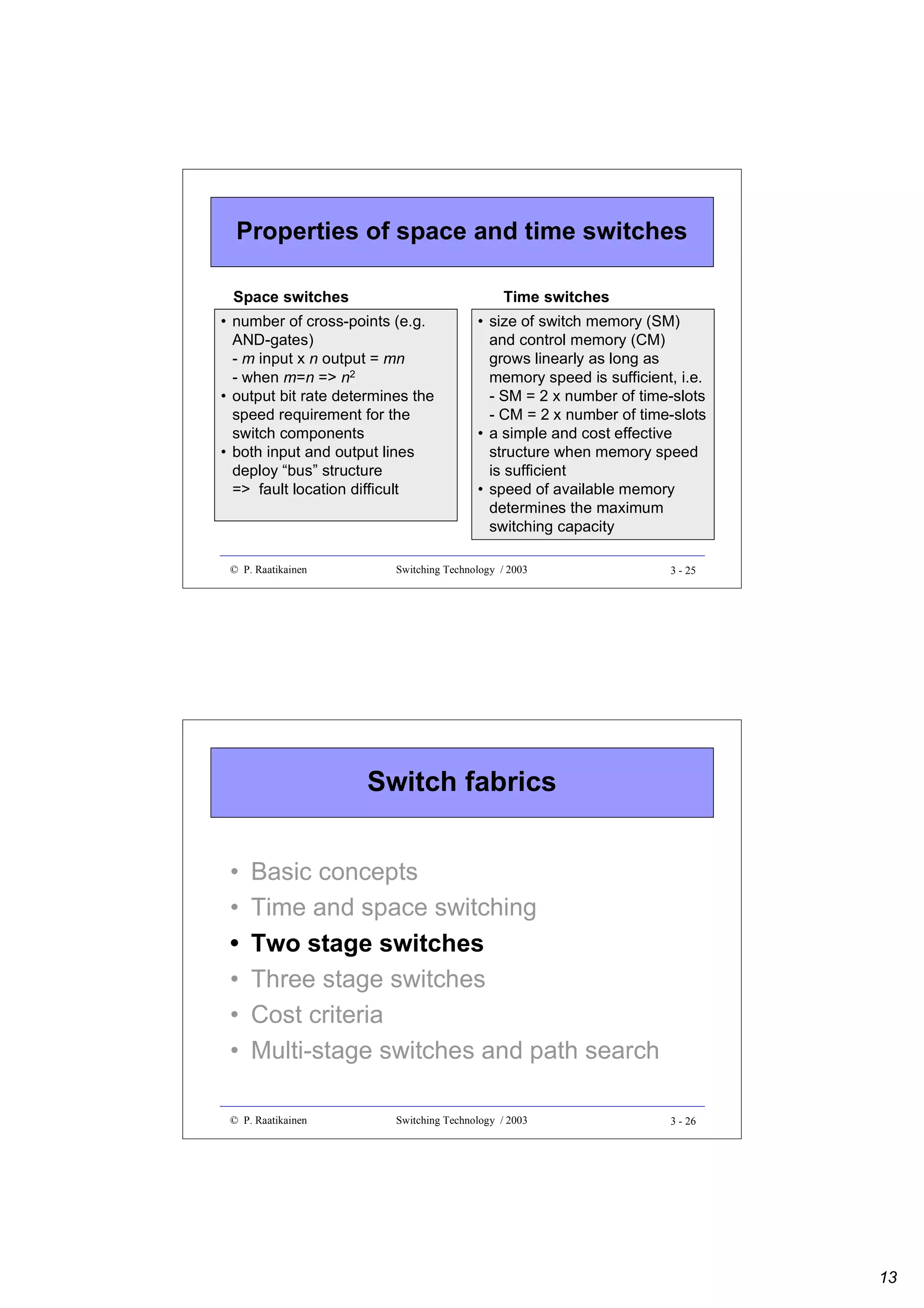

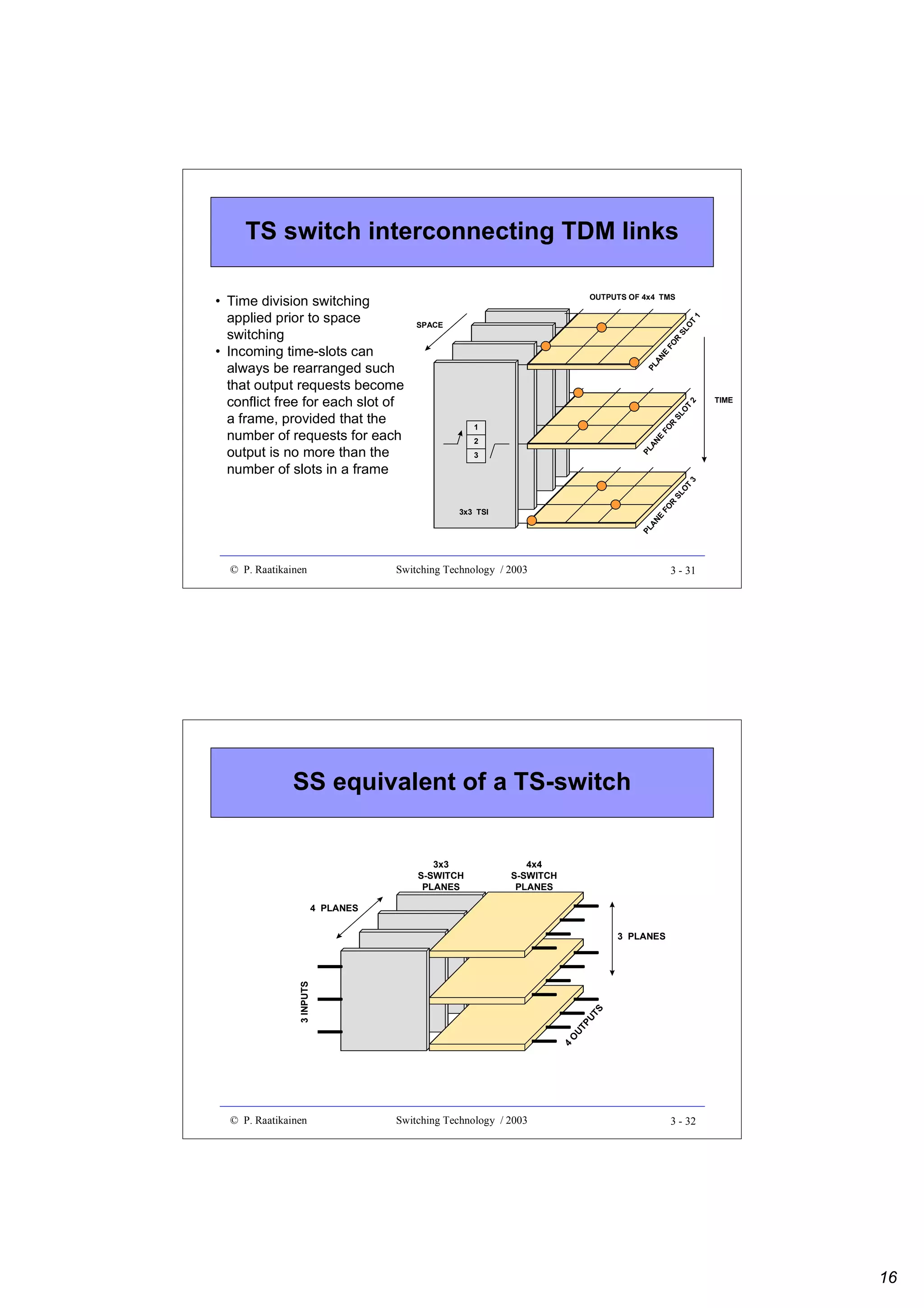

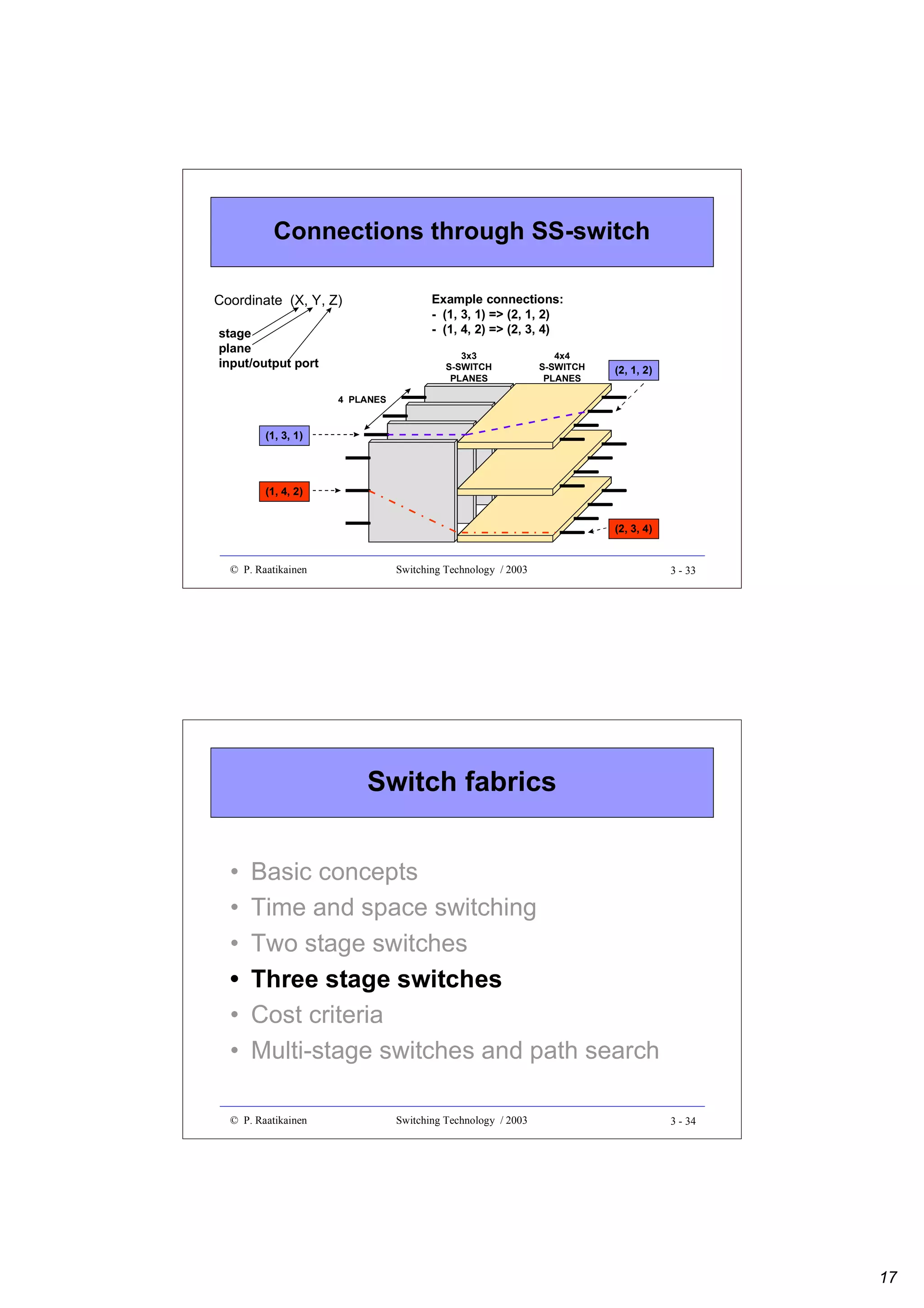

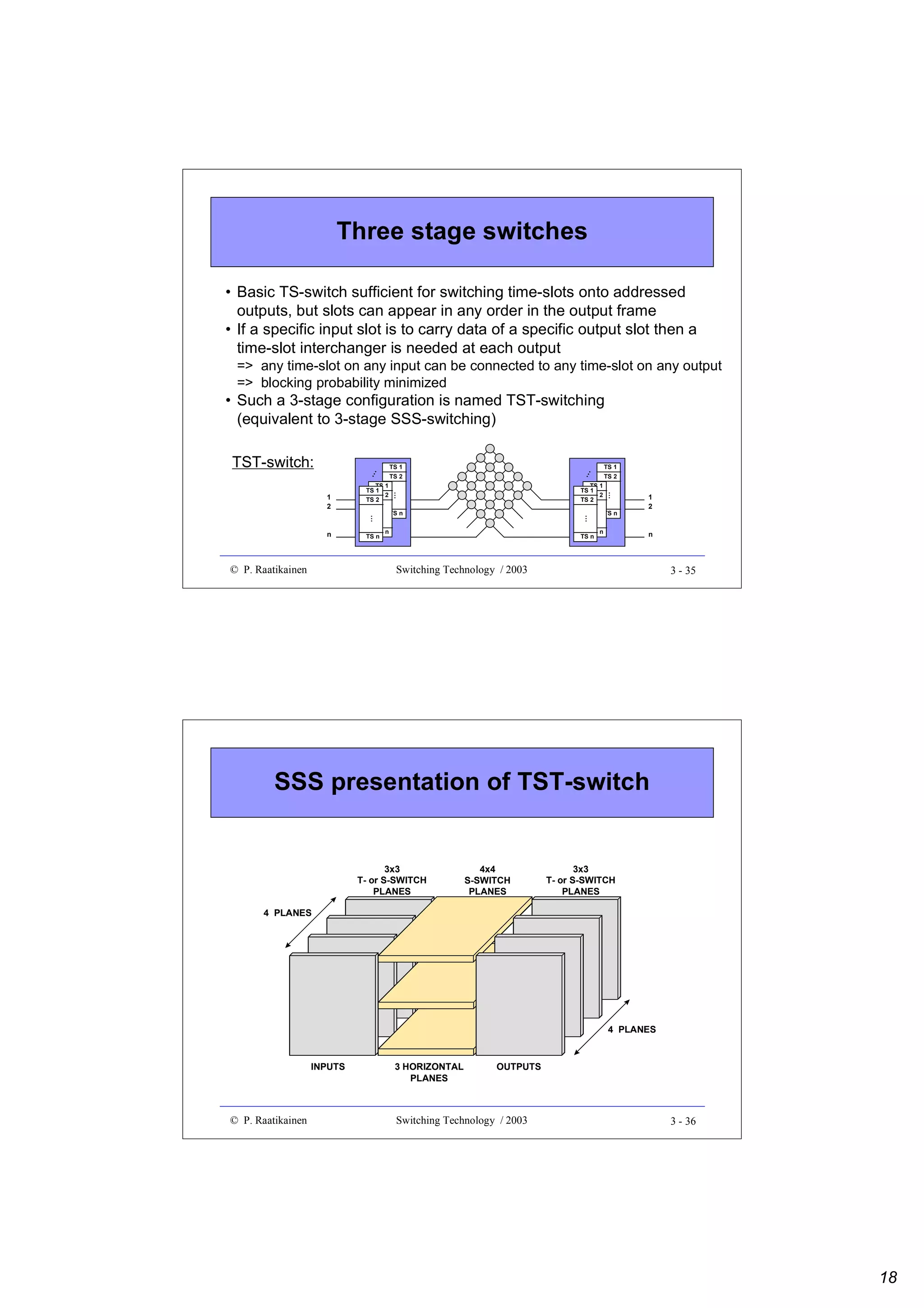

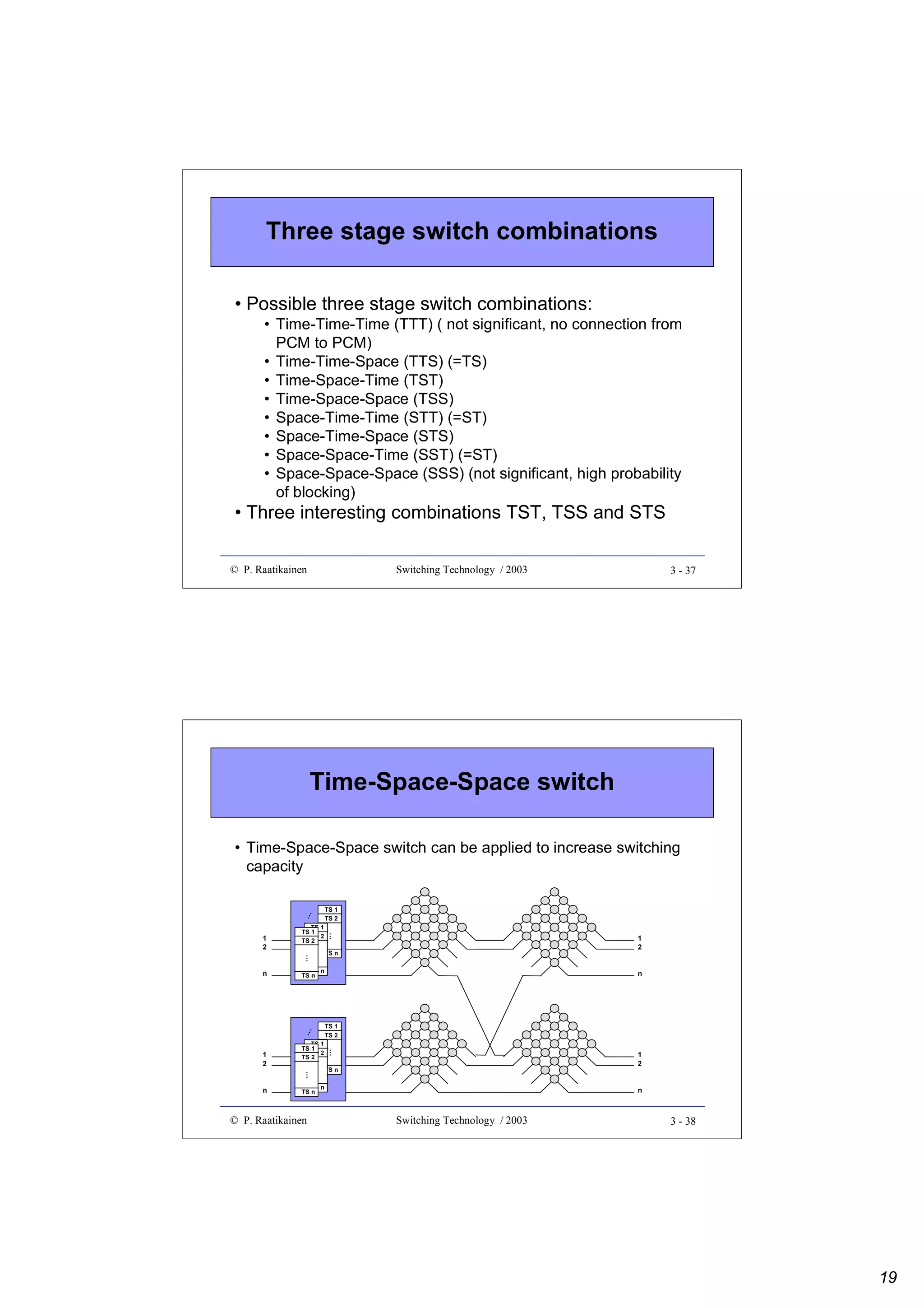

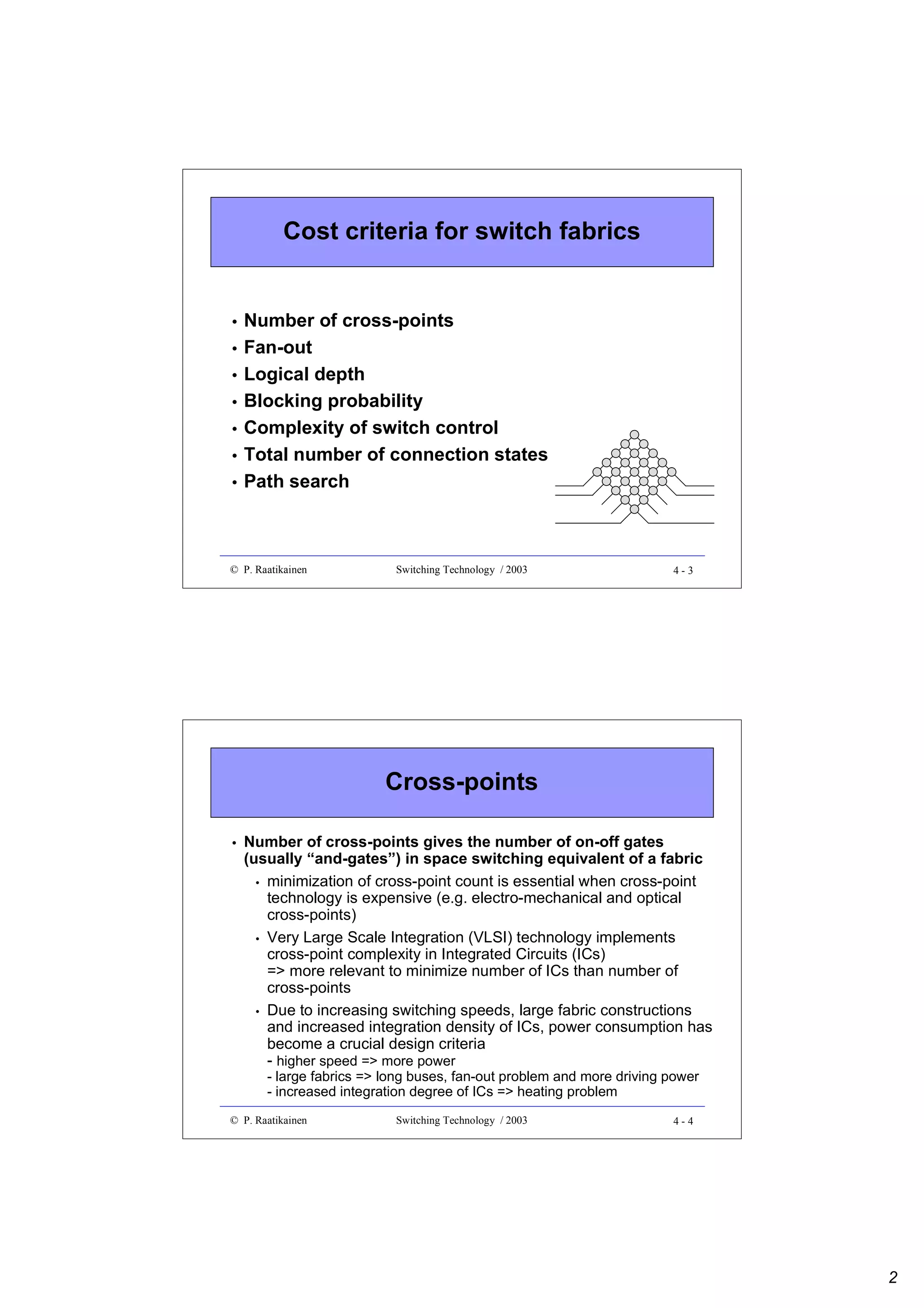

Switch fabrics

•

•

•

•

•

•

Basic concepts

Time and space switching

Two stage switches

Three stage switches

Cost criteria

Multi-stage switches and path search

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

3 - 12

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-65-2048.jpg)

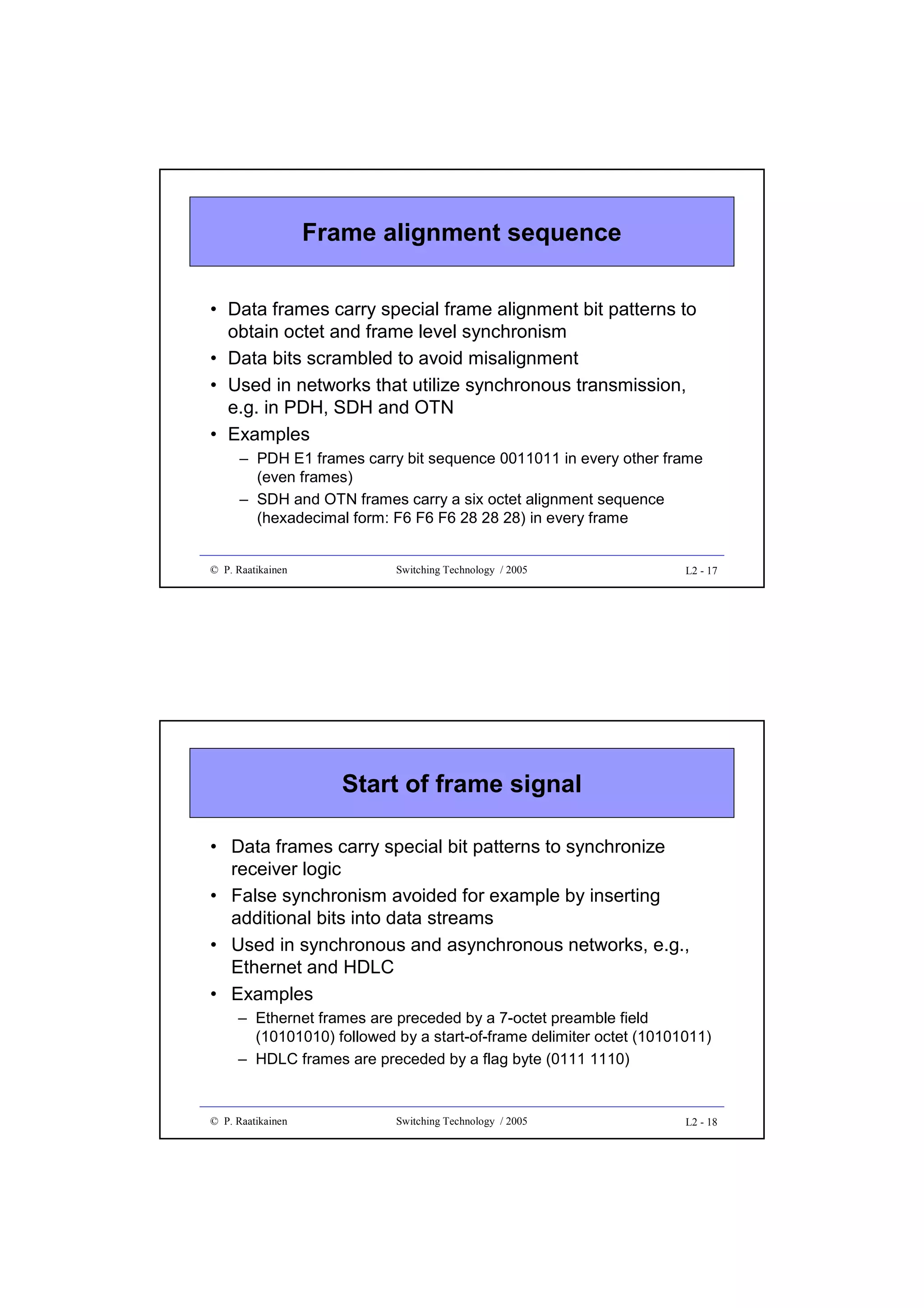

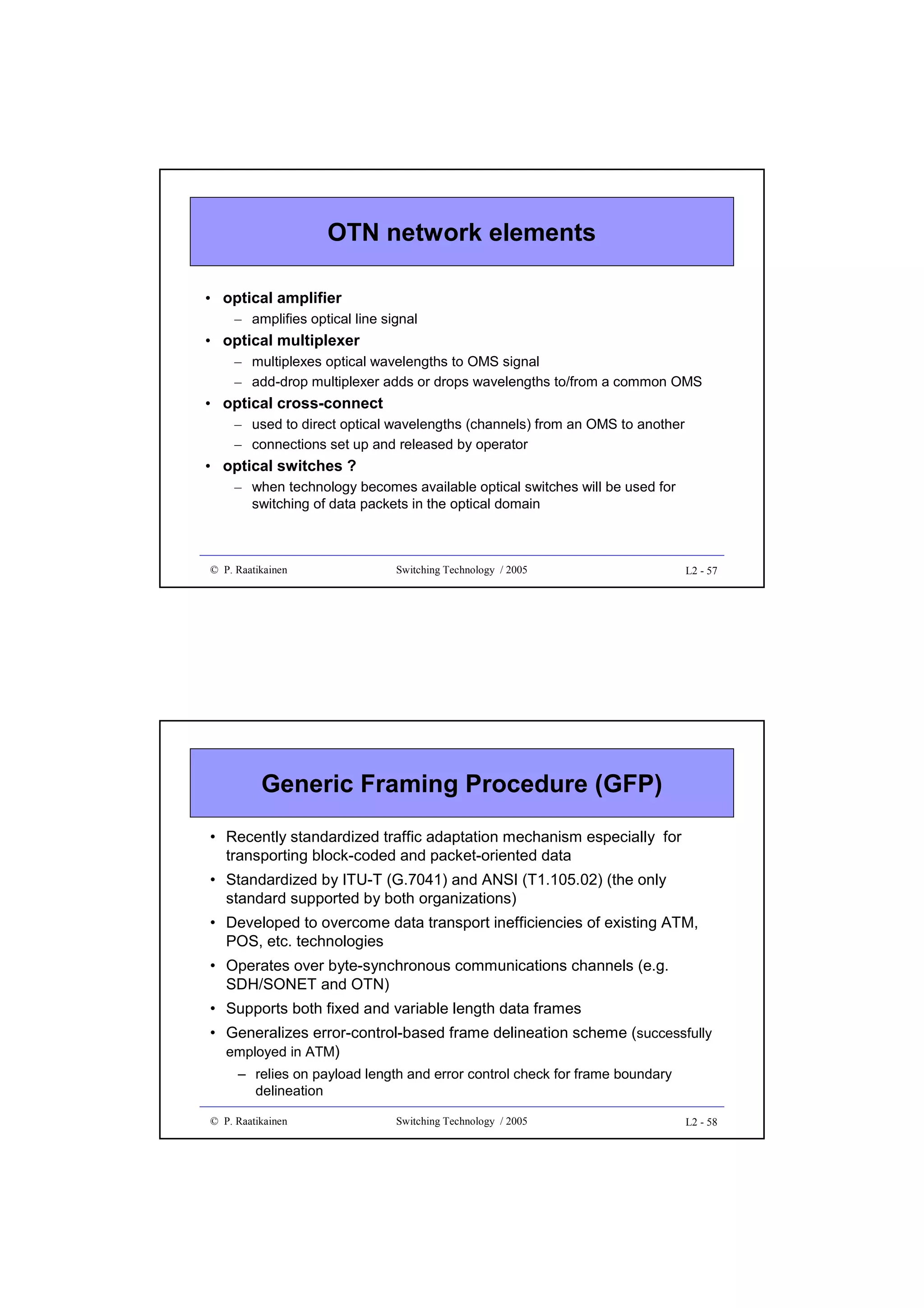

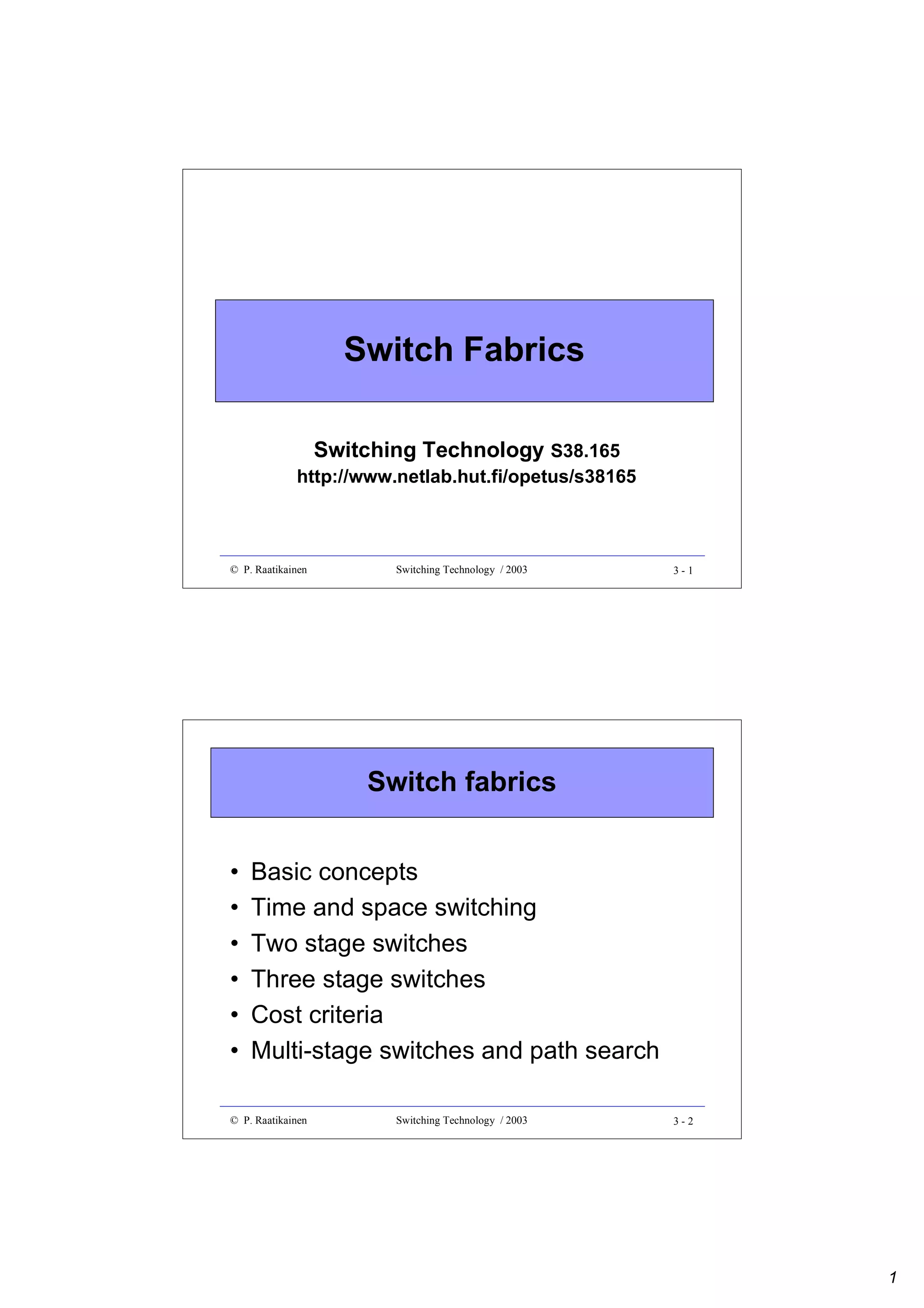

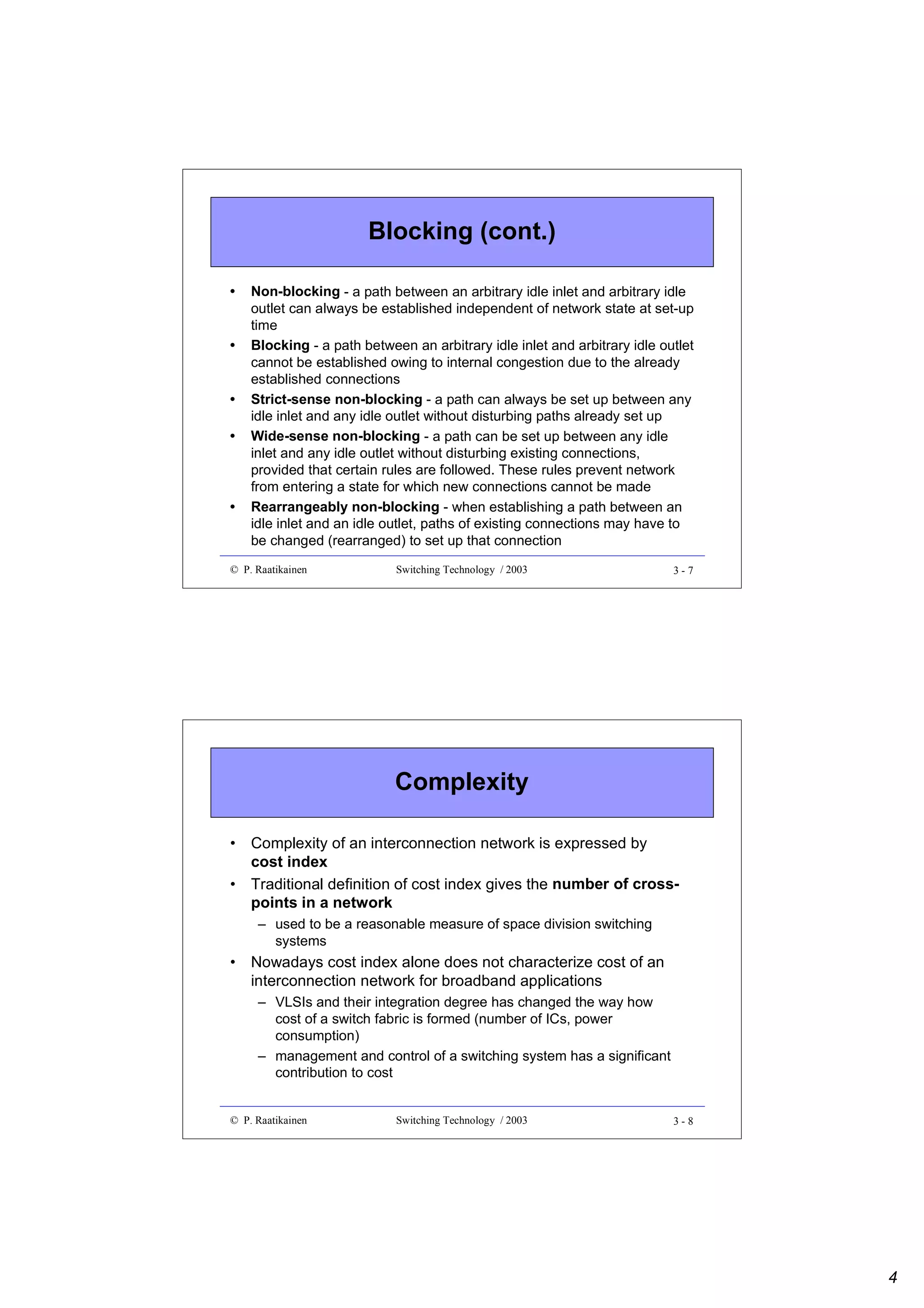

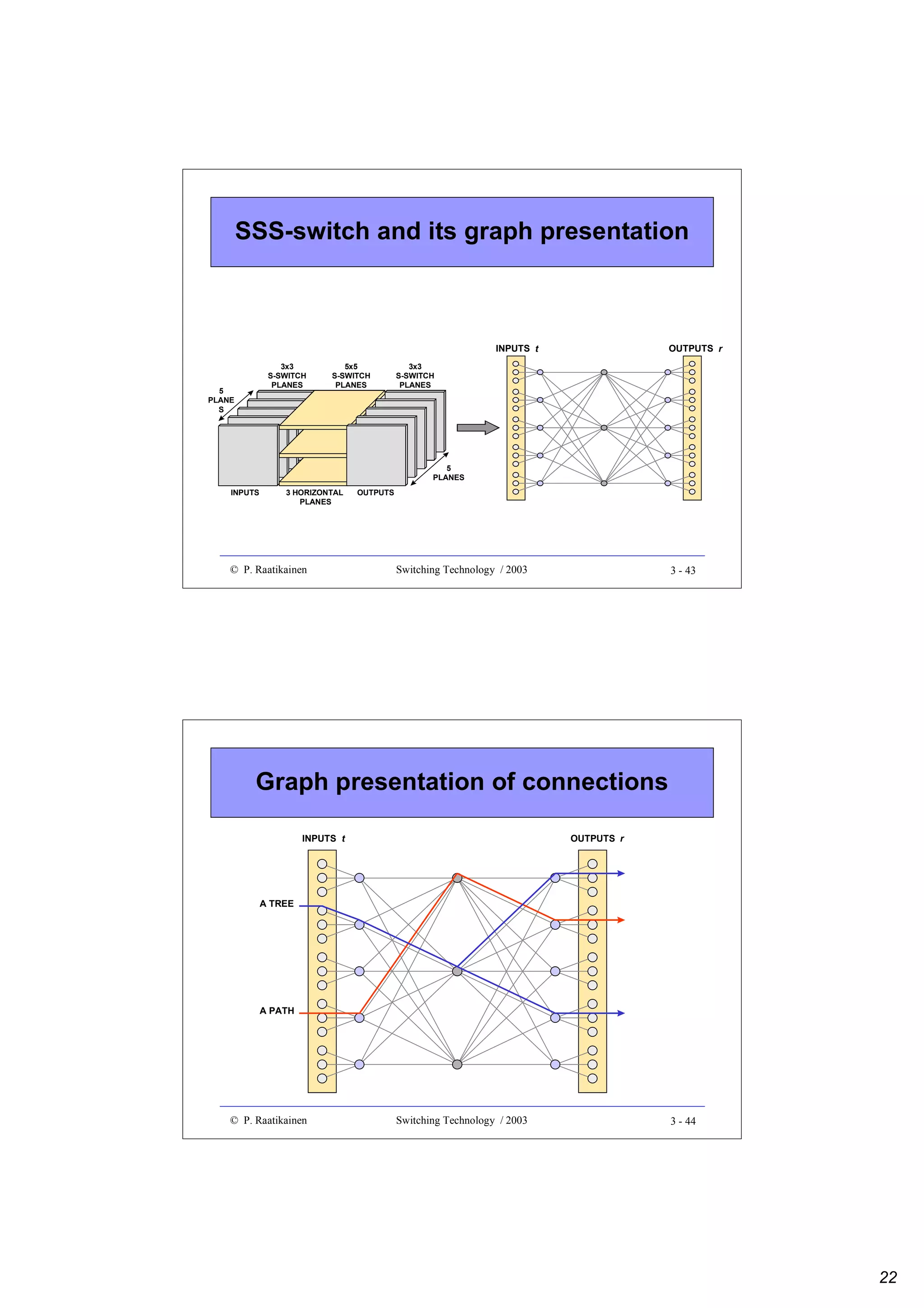

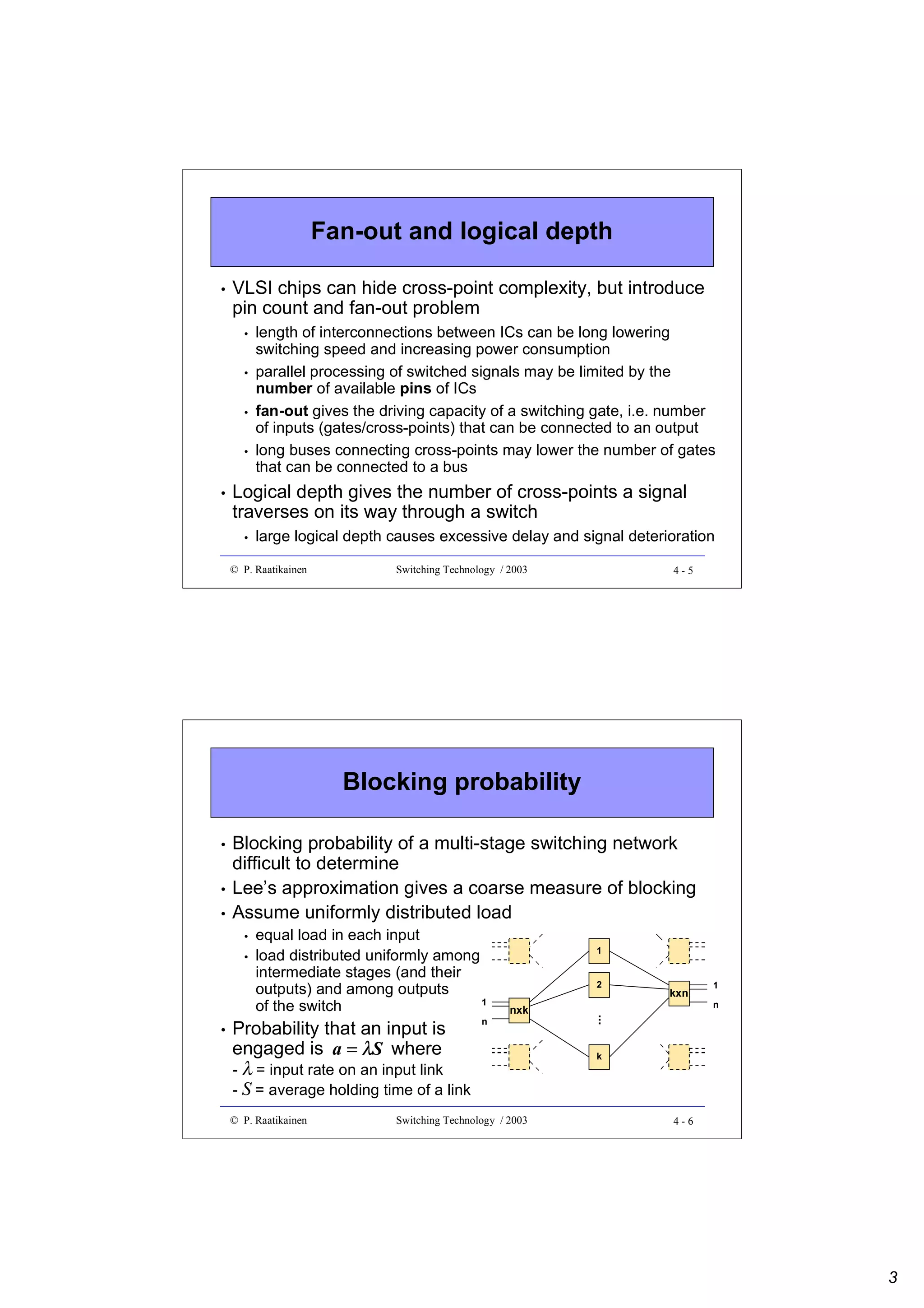

![Blocking probability (cont.)

•

•

•

Under the assumption of uniformly distributed load,

probability that a path between any two switching blocks

≥

is engaged is p = an/k (k≥n)

Probability that a certain path from an input block to an

output block is engaged is 1 - (1-p)2 where the last term is

the probability that both (input and output) links are

disengaged

Probability that all k paths between an input switching

block and an output switching block are engaged is

B = [1 - (1- an/k )2 ]k

which is known as Lee’s approximation

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

4-7

Control complexity

•

Give a graph G , a control algorithm is needed to find and set up

paths in G to fulfill connection requirements

•

Control complexity is defined by the hardware (computation and

memory) requirements and the run time of the algorithm

•

Amount of computation depends on blocking category and degree of

blocking tolerated

•

In general, computation complexity grows exponentially as a function

of the number of terminal

•

There are interconnection networks that have a regular structure for

which control complexity is substantially reduced

•

There are also structures that can be distributed over a large number

of control units

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

4-8

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-85-2048.jpg)

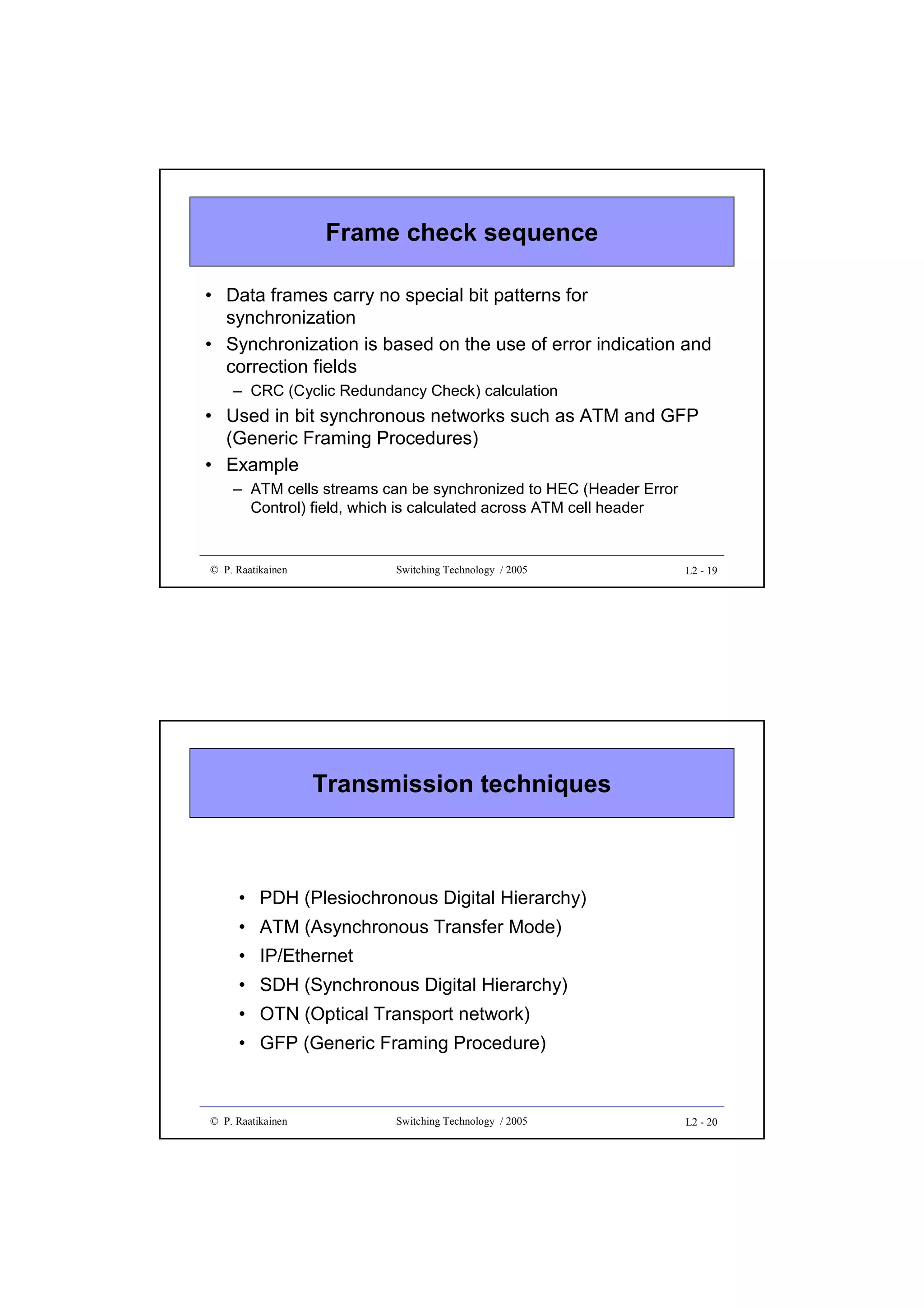

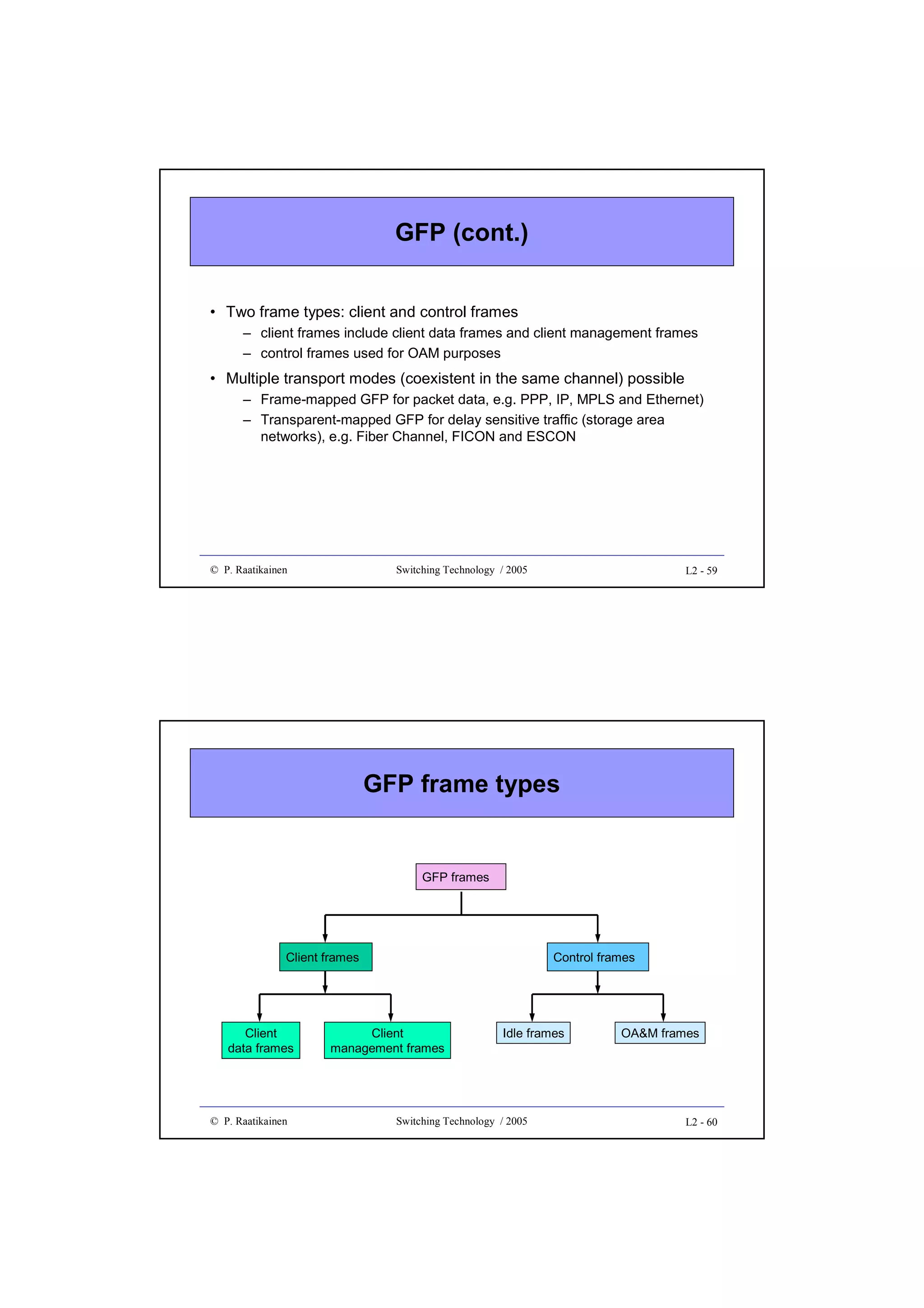

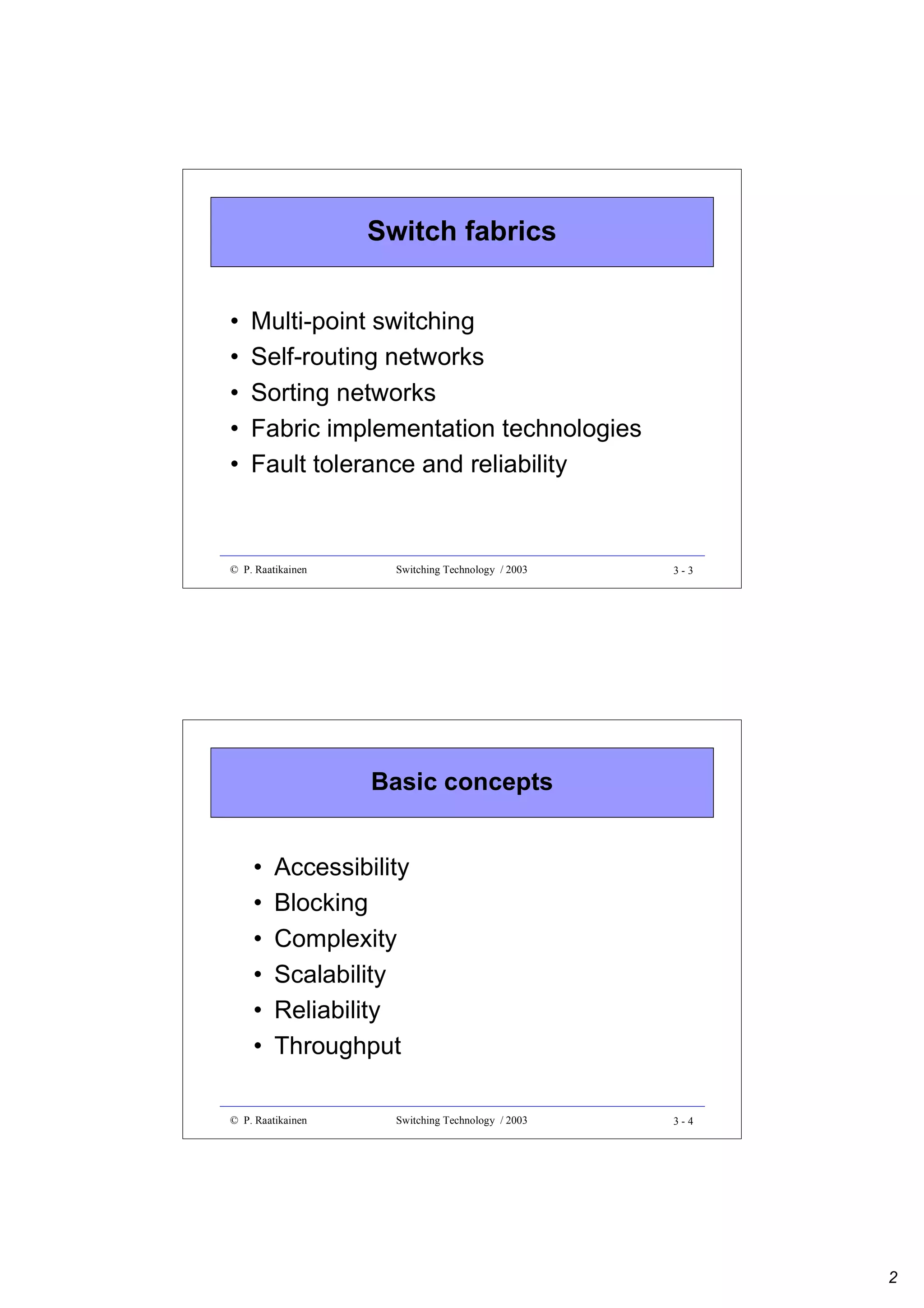

![Management complexity

•

•

Network management involves adaptation and maintenance of a

switching network after the switching system has been put in place

Network management deals with

• failure events and growth in connectivity demand

• changes of traffic patterns from day to day

• overload situations

• diagnosis of hardware failures in switching system, control system

as well as in access and trunk network

- in case of failure, traffic is rerouted through redundant built-in

hardware or via other switching facilities

- diagnosis and failure maintenance constitute a significant part of

software of a switching system

•

In order for switching cost to grow linearly in respect to total traffic,

switching functions (such as control, maintenance, call processing and

interconnection network) should be as modular as possible

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

4-9

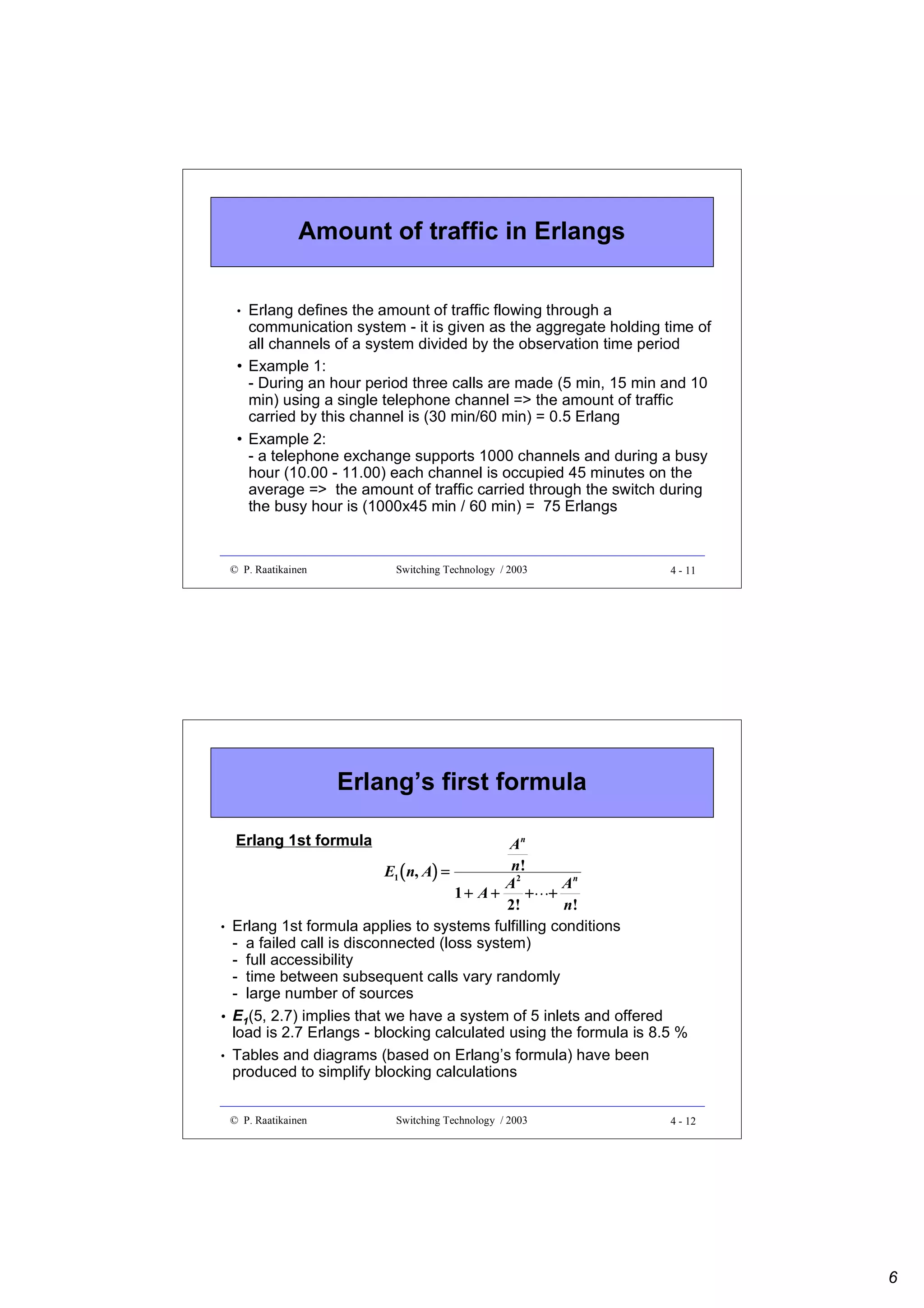

Example 1

•

A switch with

•

•

•

•

a capacity of N simultaneous calls

average occupancy on lines during busy hour is X Erlangs

Y % requirement for internal use

notice that two (one-way) connections are needed for a call

requires a switch fabric with M = 2 x [(100+Y)/100] x(N/X) inputs

and outputs.

•

If N = 20 000, X = 0.72 and Y = 10%

=> M = 2 x 1.1 x 20 000/0.72 = 61 112

=> corresponds to 2038 E1 links

1

2

2

M

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

1

M

4 - 10

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-86-2048.jpg)

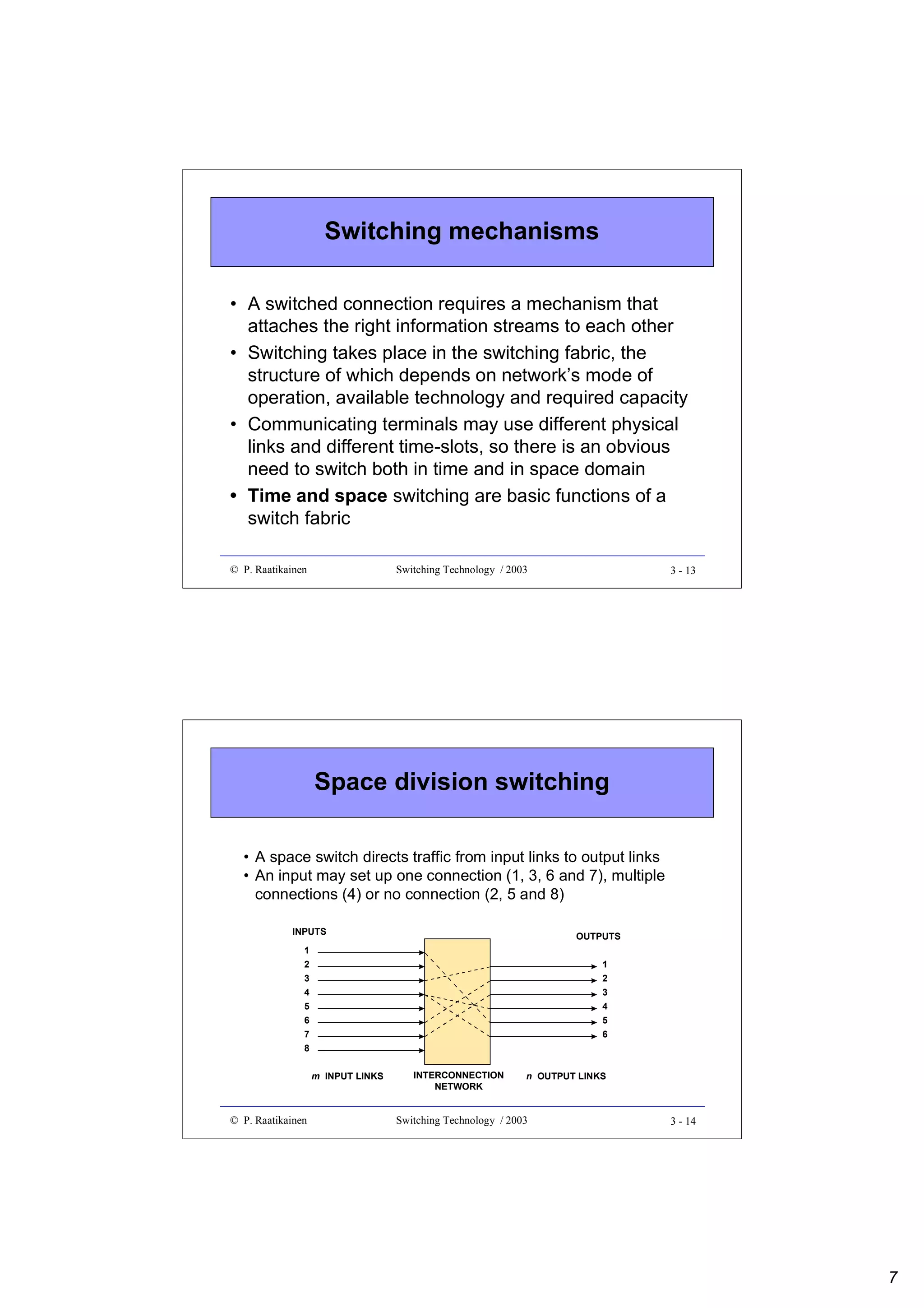

![Example 2

•

An exchange for 2000 subscribers is to be installed and it is

required that the blocking probability should be below 10 %.

If E2 links are used to carry the subscriber traffic to

telephone network, how many E2 links are needed ?

- average call lasts 6 min

- a subscriber places one call during a 2-hour busy period

(on the average)

• Amount of offered traffic is (2000x6 min /2x60 min) = 100 Erl.

• Erlang 1st formula gives for 10 % blocking and load of 100 Erl.

that n = 97

=> required number of E1 links is ceil(97/30) = 4

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

4 - 13

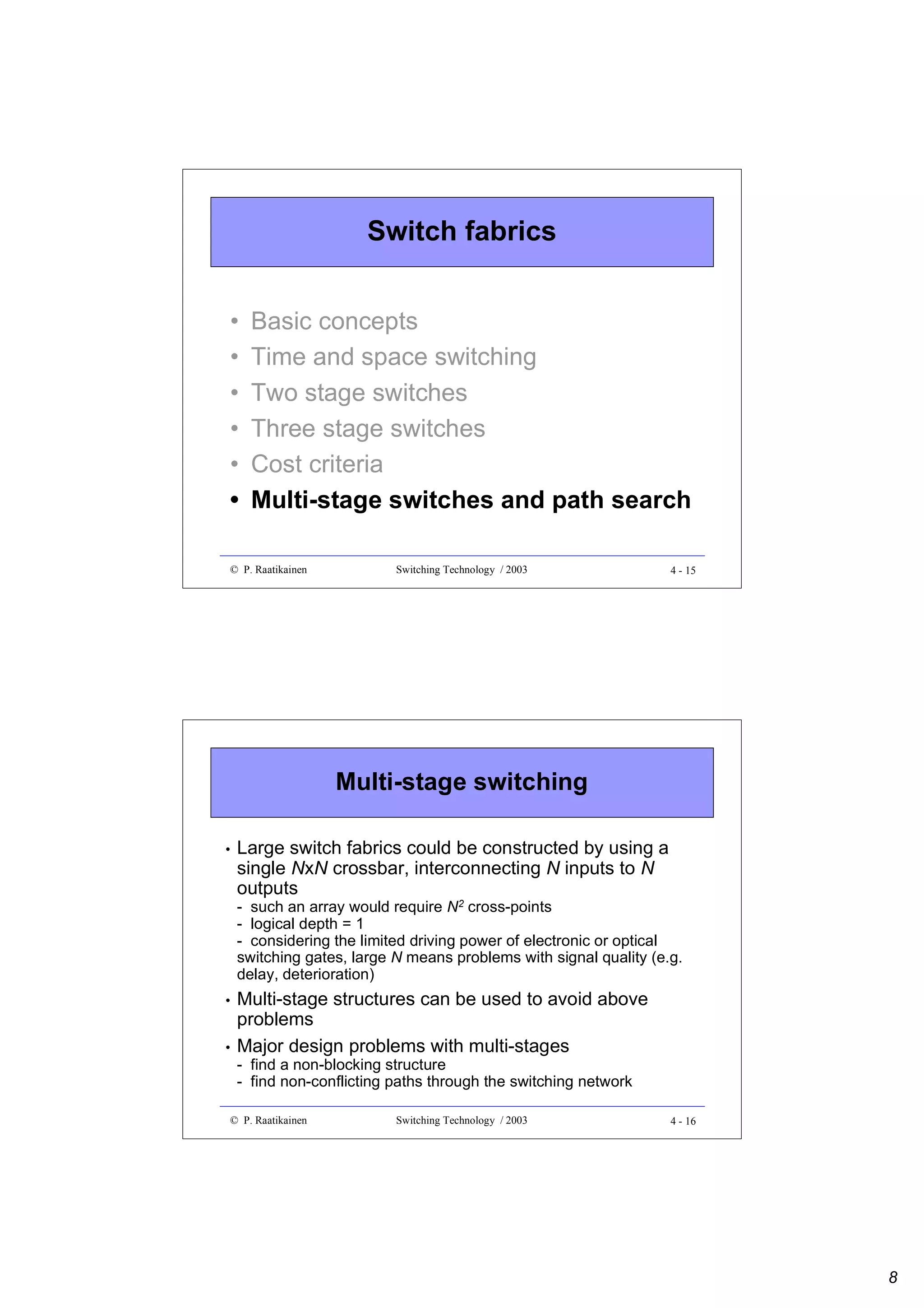

Example 3

•

•

•

Suppose driving current of a switching gate (cross-point) is 100 mA

and its maximum input current is 8 mA

How many output gates can be connected to a bus, driven by one

input gate, if the capacitive load of the bus is negligibly small ?

Fan-out = floor[100/8] = 12

c

c

• How many output gates can be connected

to a bus driven by one input gate if load of

the bus corresponds to 15 % of the load of

a gate input) ?

• Fan-out = floor[100/(1.15x8)] = 10

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

c

1

c

2

…

M

4 - 14

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-88-2048.jpg)

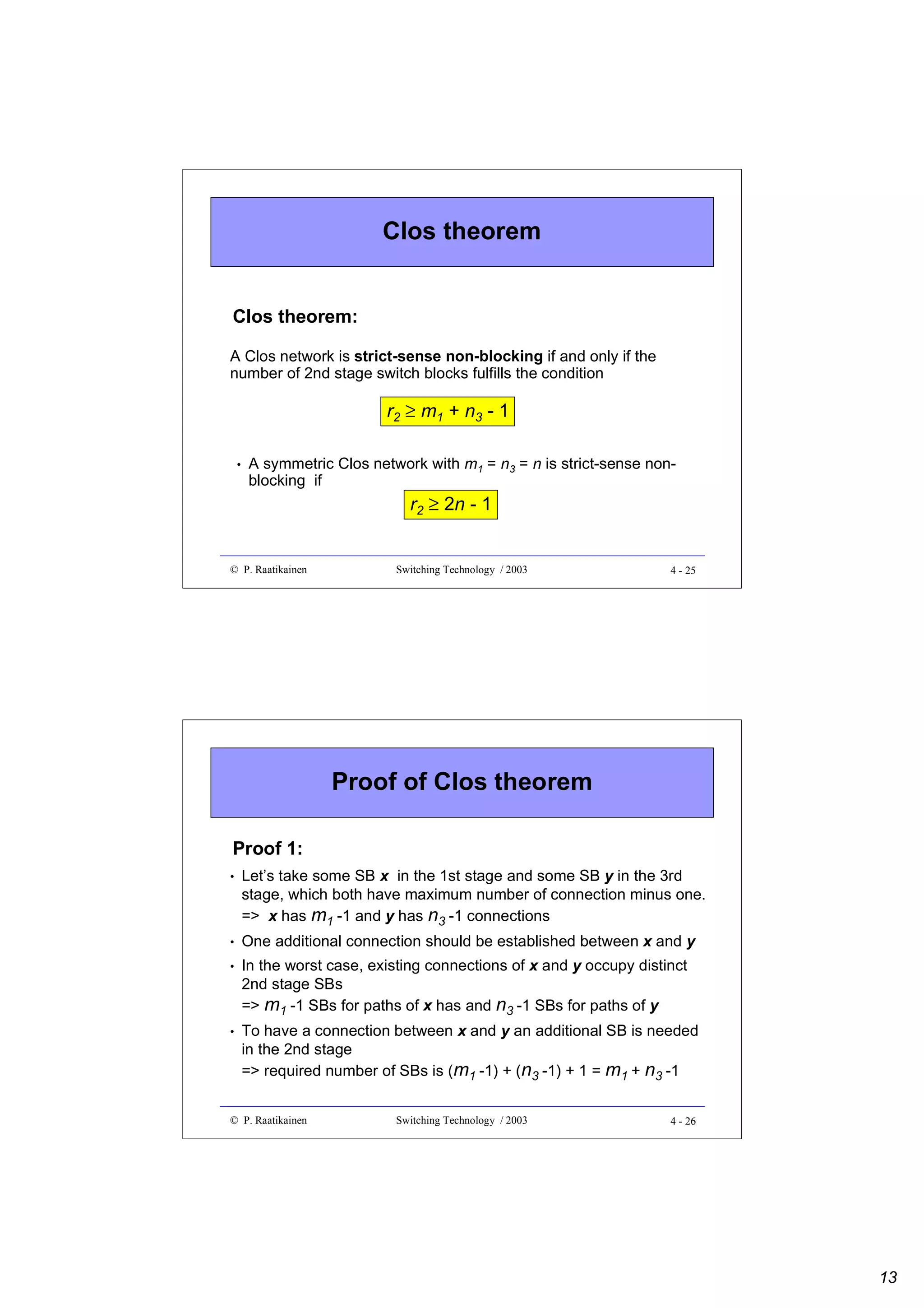

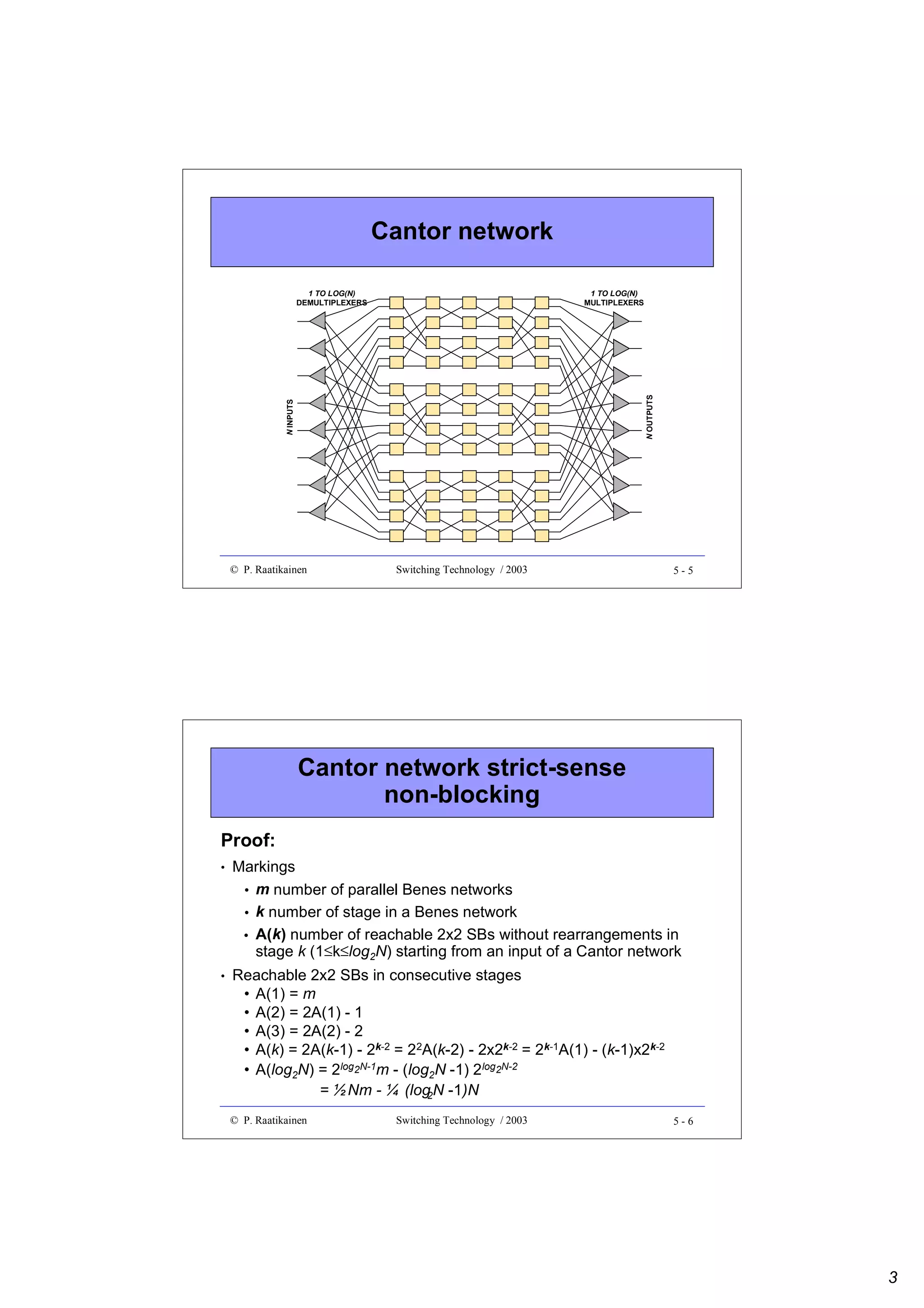

![Cantor network strict-sense

non-blocking (cont.)

•

Cantor network is symmetrical at the middle

=> the same number of center stage nodes are reachable by an

output of a Cantor network

•

Total number of SBs in center stages is Nm/2 (m Benes networks)

•

If the number of center stage SBs reached by an input and an

output exceeds Nm/2 then there must be a SB reachable from both

•

Hence strict-sense non-blocking is achieved if

2 [1 Nm - 1 (log 2 N - 1)N ] >

2

4

Nm

2

=> m > log2N - 1

Notice that a strict-sense non-blocking Cantor network is

constructed of log2N rearrangeably non-blocking Benes networks

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

5-7

N INPUTS

N OUTPUTS

Visualization of proof

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

5-8

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-107-2048.jpg)

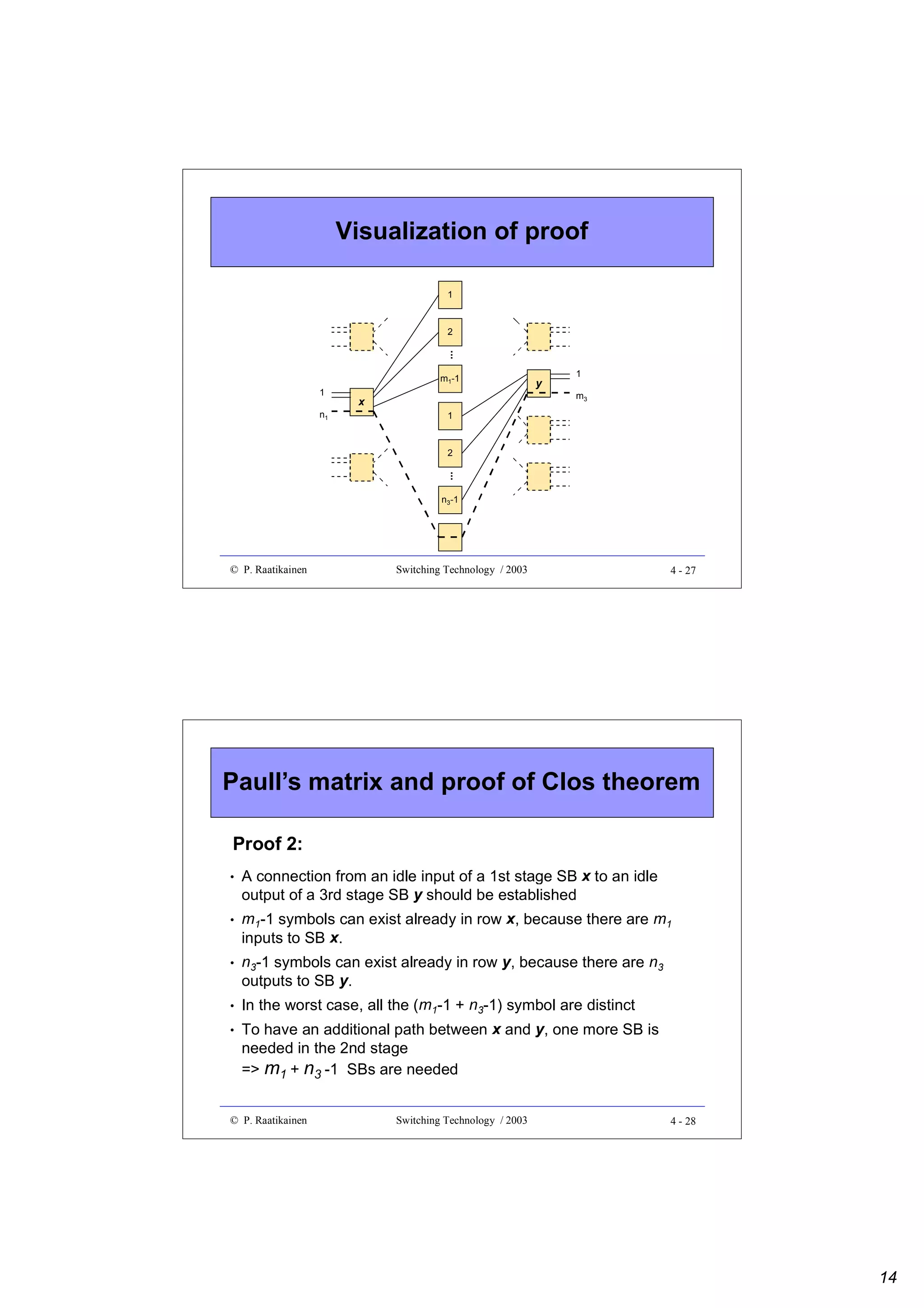

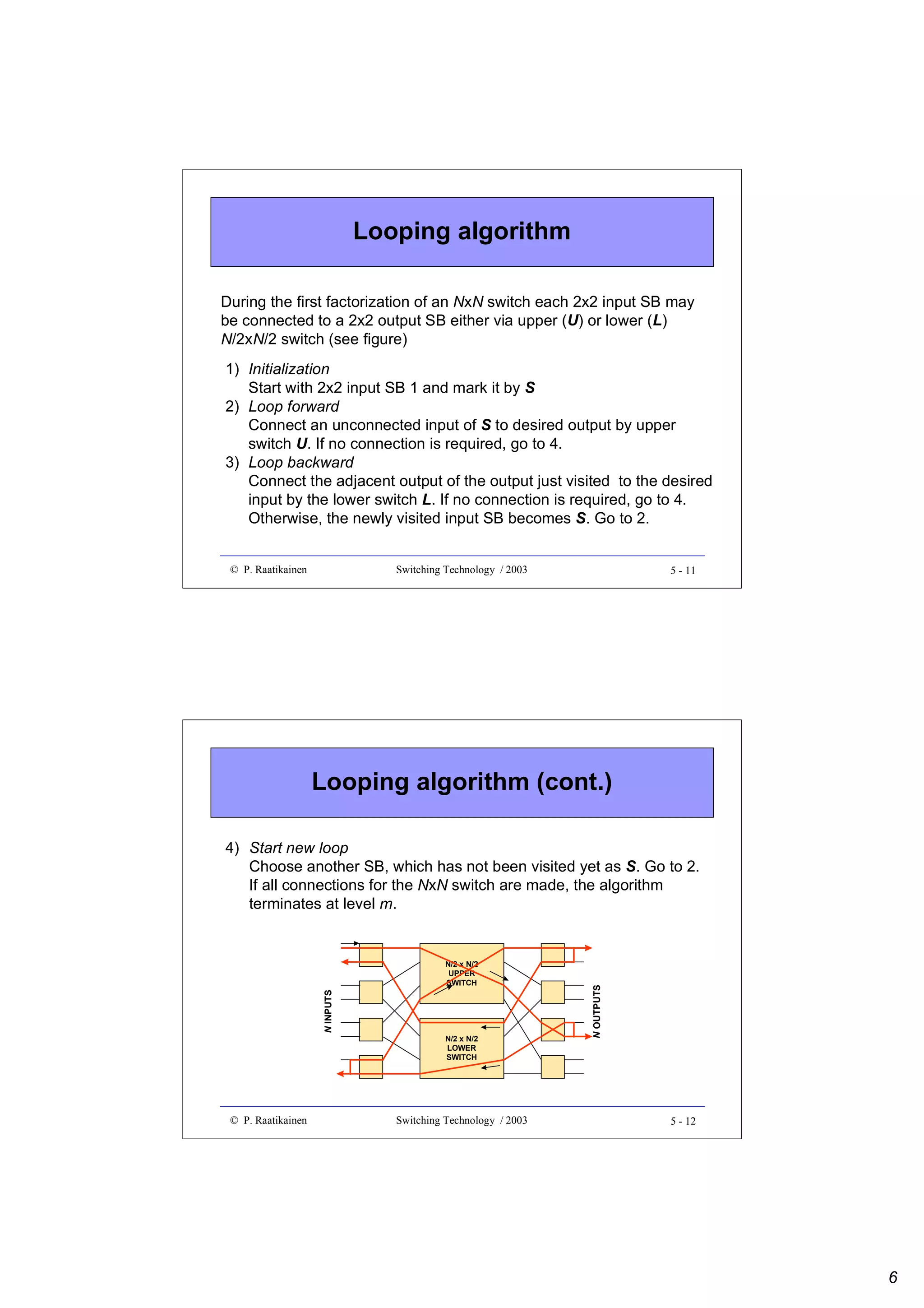

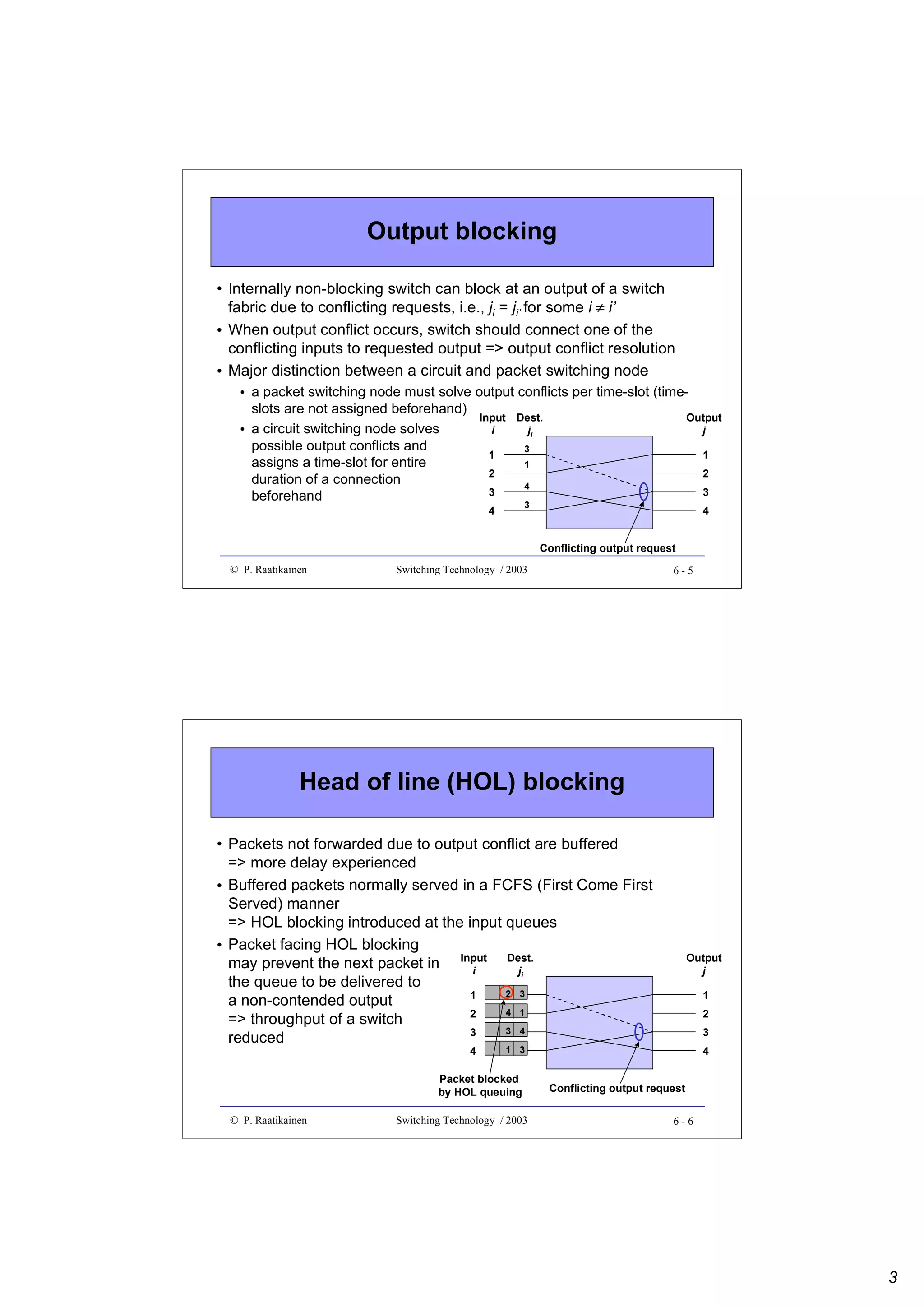

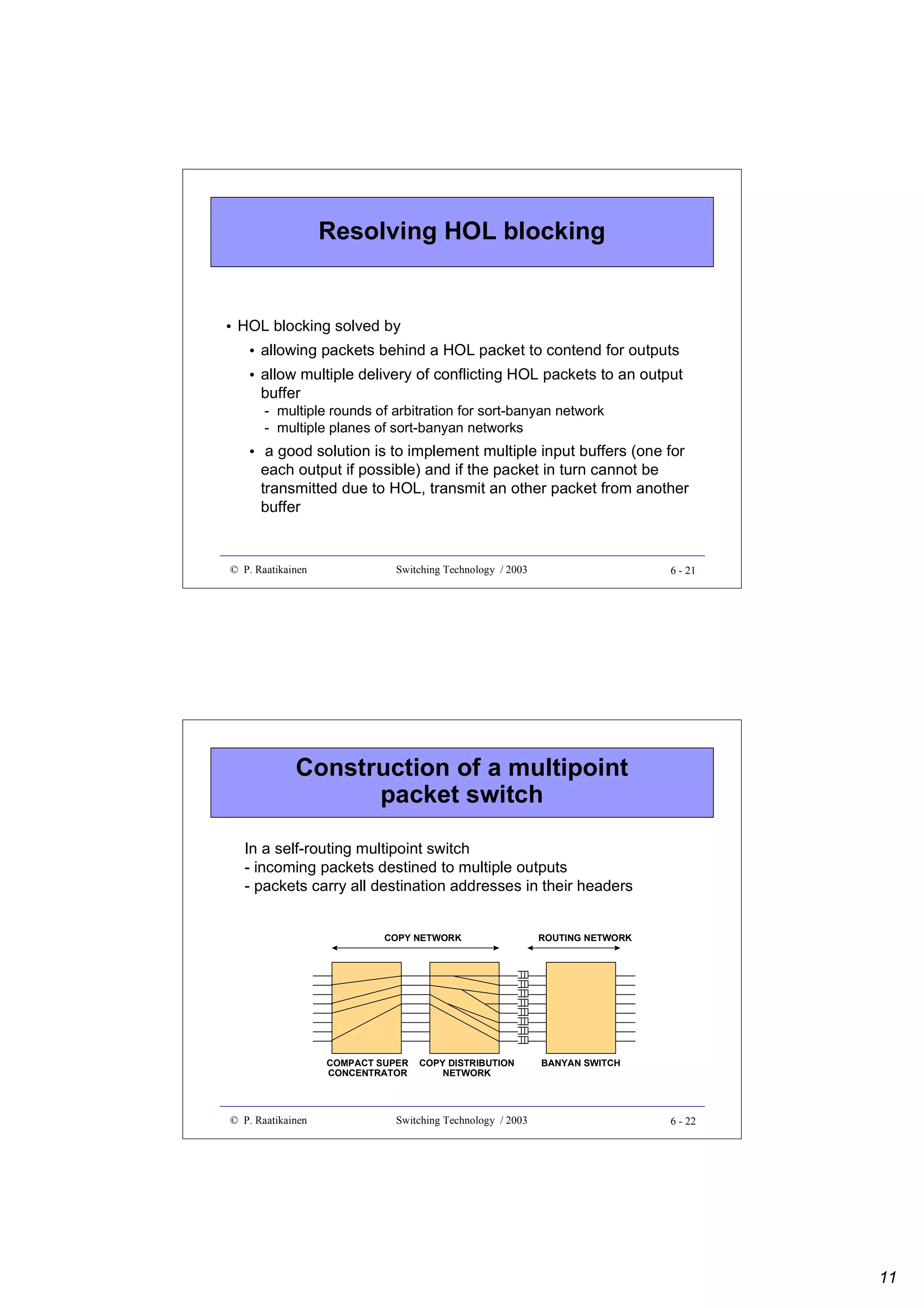

![Merge-sorting algorithm (cont.)

• Merging of two sorted lists (N/2 numbers in each) requires N

binary sorts

• Total complexity of sorting N numbers is given by

C(N) = 2C(N/2) = N + 2(N/2 + 2C(N/4)) = … = Nlog2N

• Due to sequential nature of procedure Merge the sorting takes at

least O(N) time

1

4

6

10

11

15

17

20

© P. Raatikainen

Compare numbers

at the top of lists

then merge

2

5

7

9

12

14

16

24

Switching Technology / 2003

6 - 11

Odd-even merging

Recursive construction of an odd-even merger

...

¥ ¥

...

...

...

e0

e1

e2

e3

e4

eN/2-5

eN/2-4

eN/2-3

eN/2-2

eN/2-1

cN/2-2

cN/2-1

Odd

merger

N/2 dN/2-3

...

bN/2-4

bN/2-3

bN/2-2

bN/2-1

...

...

...

d0

d1

...

b0

b1

© P. Raatikainen

¥ ¥

...

aN/2-2

aN/2-1

Even

merger

N/2

c0

c1

c2

...

a0

a1

a2

a3

...

- number of sorting stages is log2N

- number of sorting elements is 0.5N [log2N-1]+1

dN/2-2

dN/2-1

Switching Technology / 2003

6 - 12

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-134-2048.jpg)

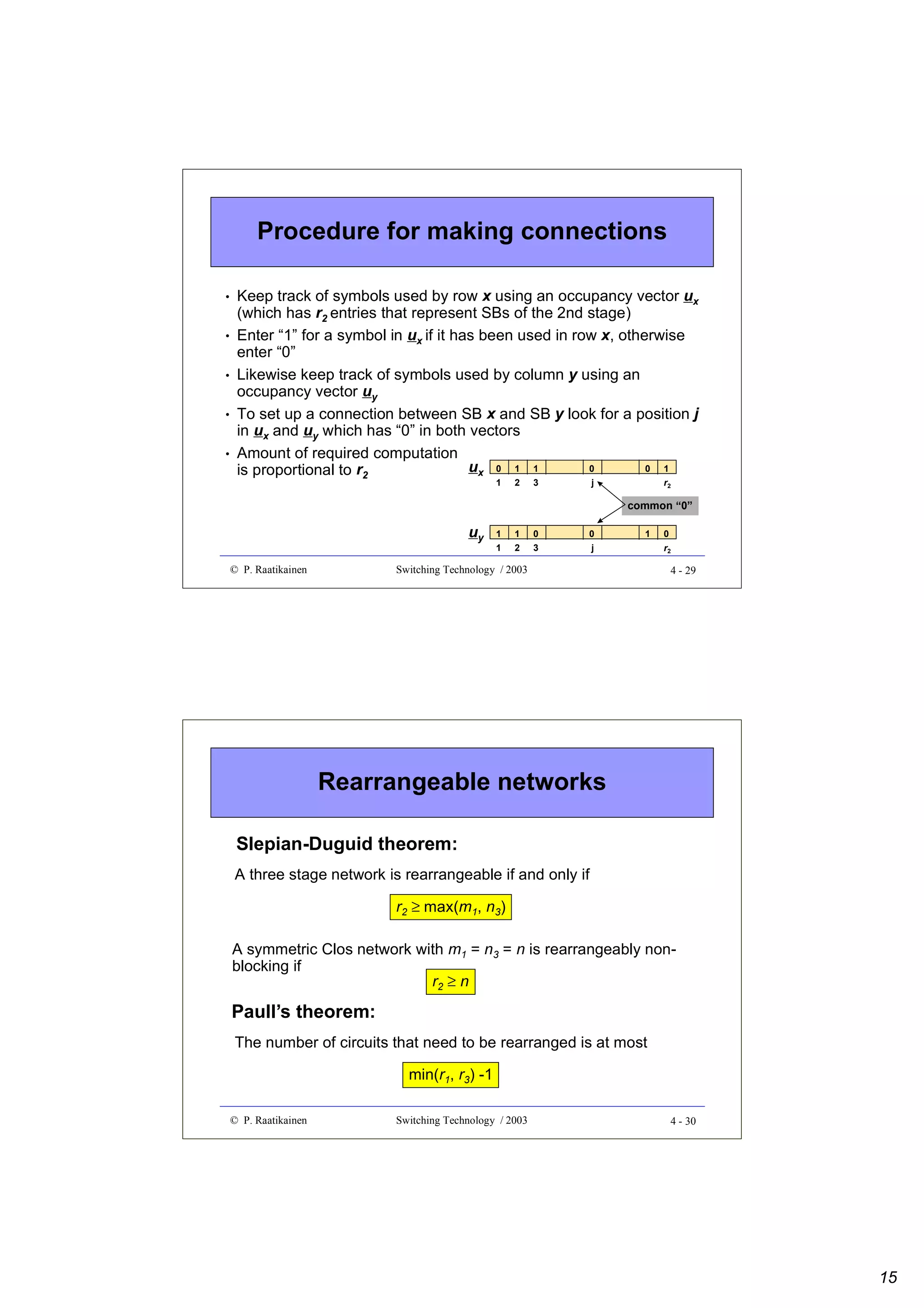

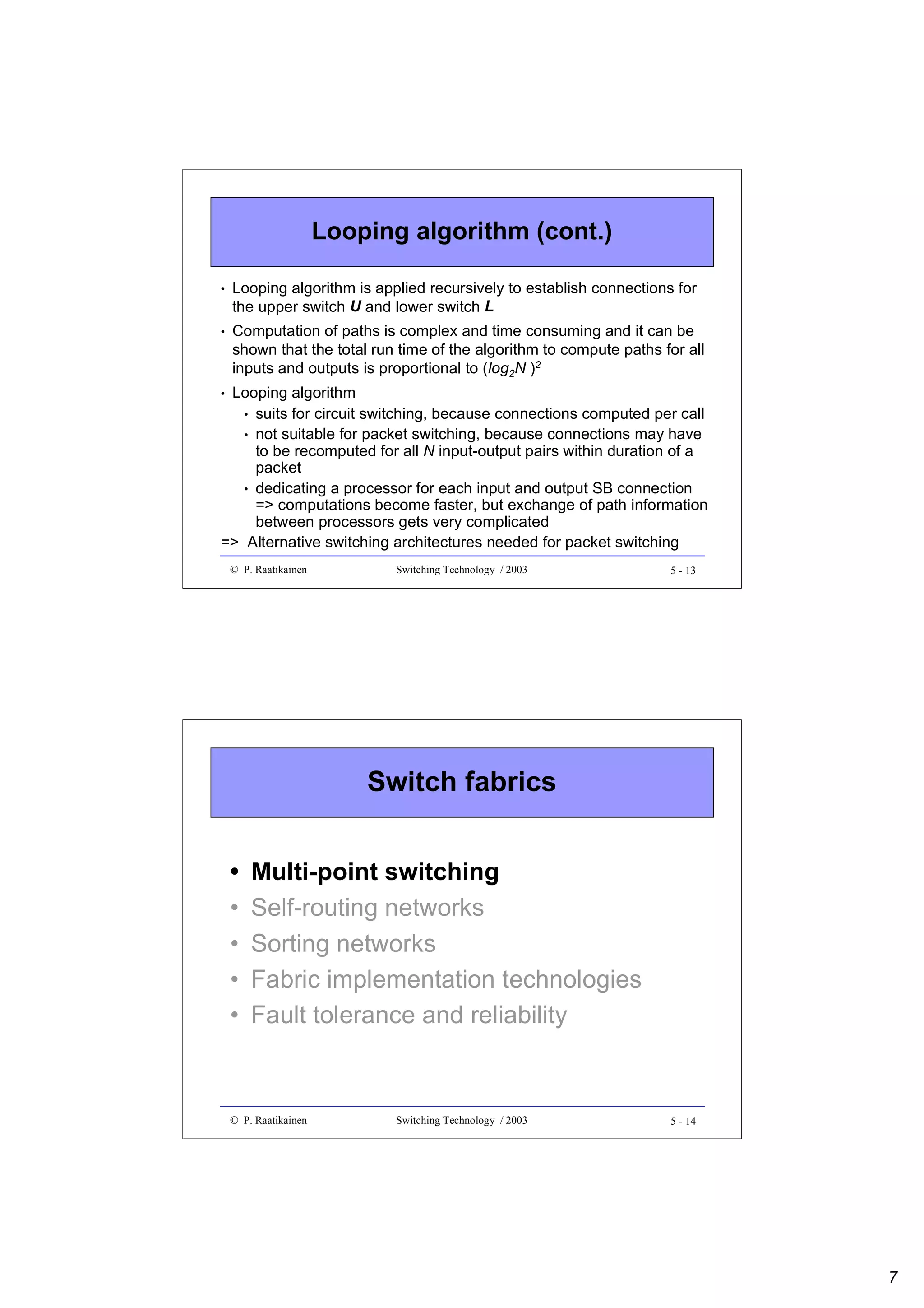

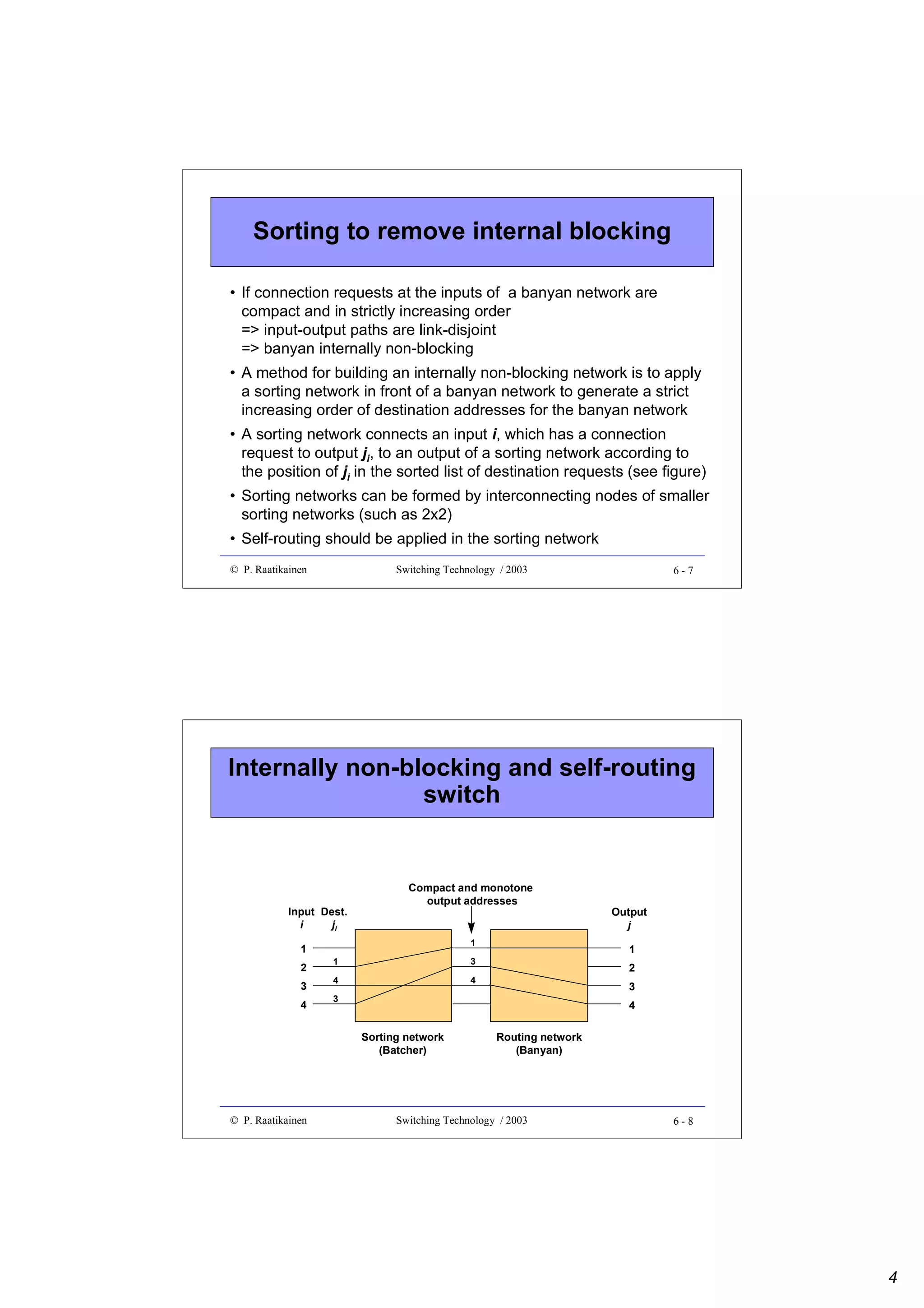

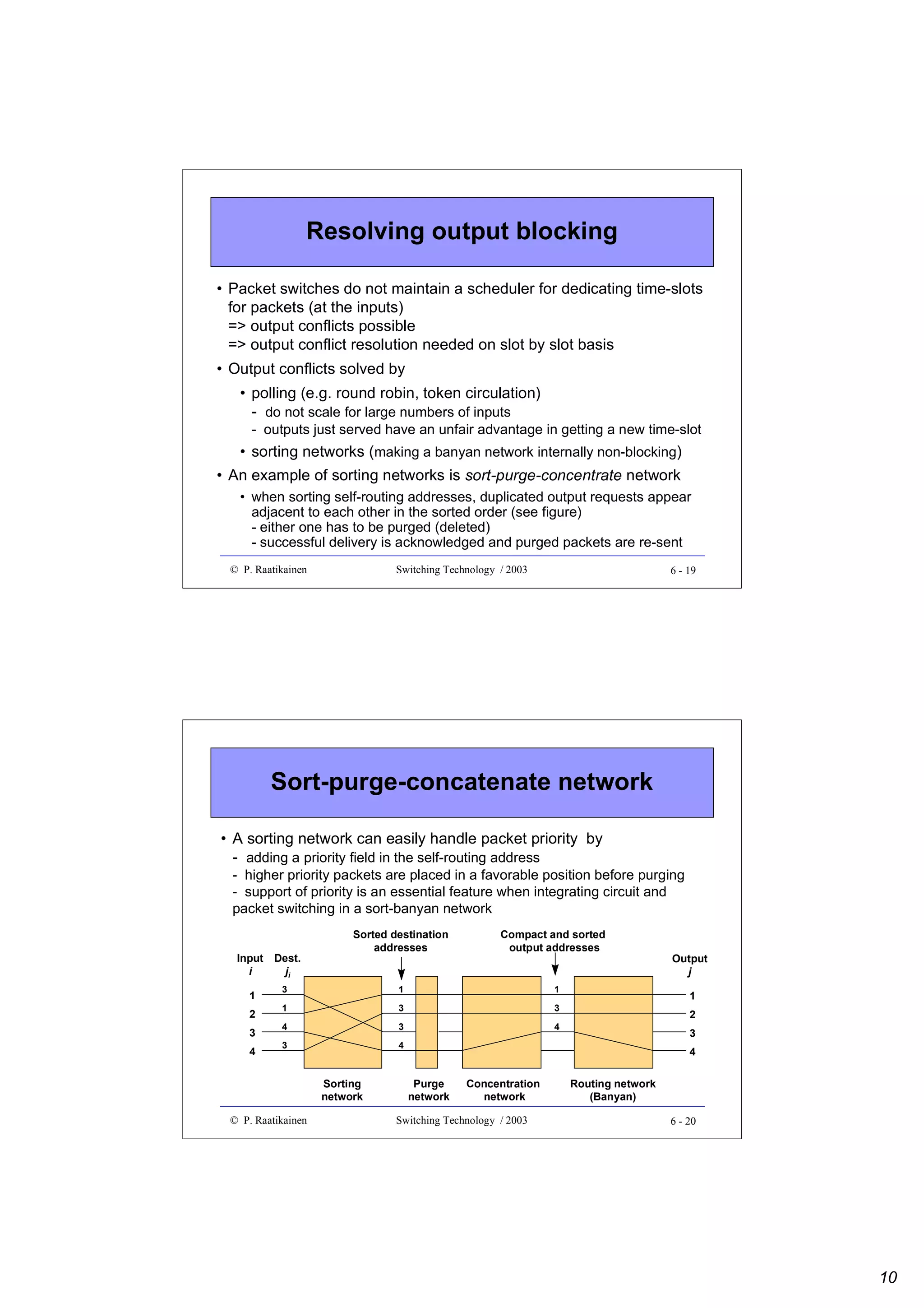

![Sorting by merging

Recursive construction of a sorting by merging network

- number of sorting stages is 0.5Nlog2N(log2N + 1)

¥

¥

Merger

N/2

¥

¥

¥

© P. Raatikainen

Merger

N

...

Merger

N/4

...

Merger

N/2

¥

Merger

N/4

...

...

aN-2

aN-1

Merger

N/4

¥

aN/2

aN/2+1

e0

¥

aN/2-1

...

...

...

aN/2-2

Merger

N/4

¥

a1

¥

a0

eN-1

Switching Technology / 2003

6 - 15

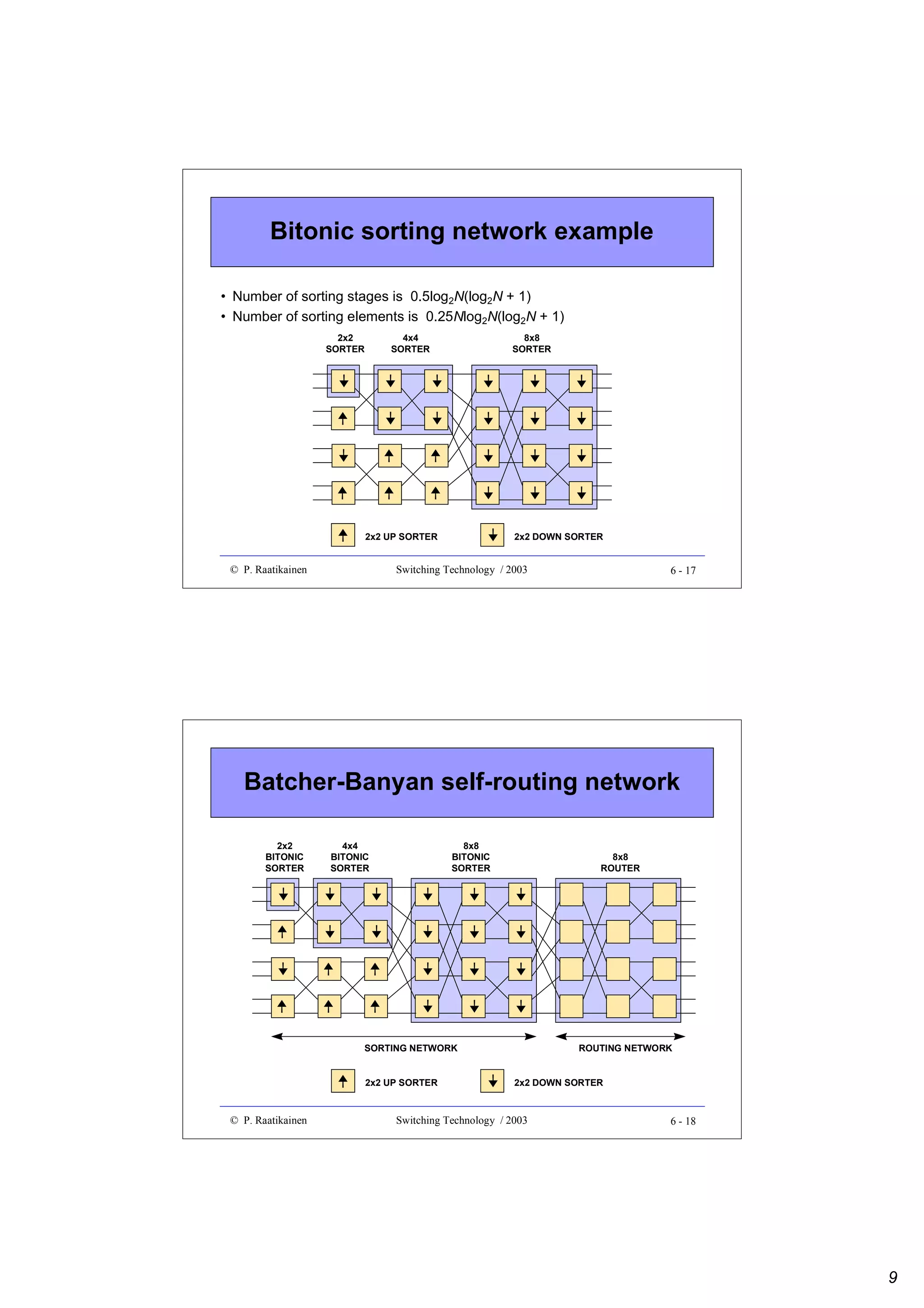

Odd-even sorting network example

• Number of sorting stages is 0.5log2N(log2N + 1)

• Number of sorting elements is 0.25N[log2N(log2N - 1) + 4] - 1

2x2

SORTER

4x4

SORTER

8x8

SORTER

¥ ¥

¥

¥ ¥

¥

¥

¥

¥ ¥

¥

¥ ¥

¥ ¥

¥

¥

¥

¥

¥ ¥

© P. Raatikainen

2x2 UP SORTER

2x2 DOWN SORTER

Switching Technology / 2003

6 - 16

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-136-2048.jpg)

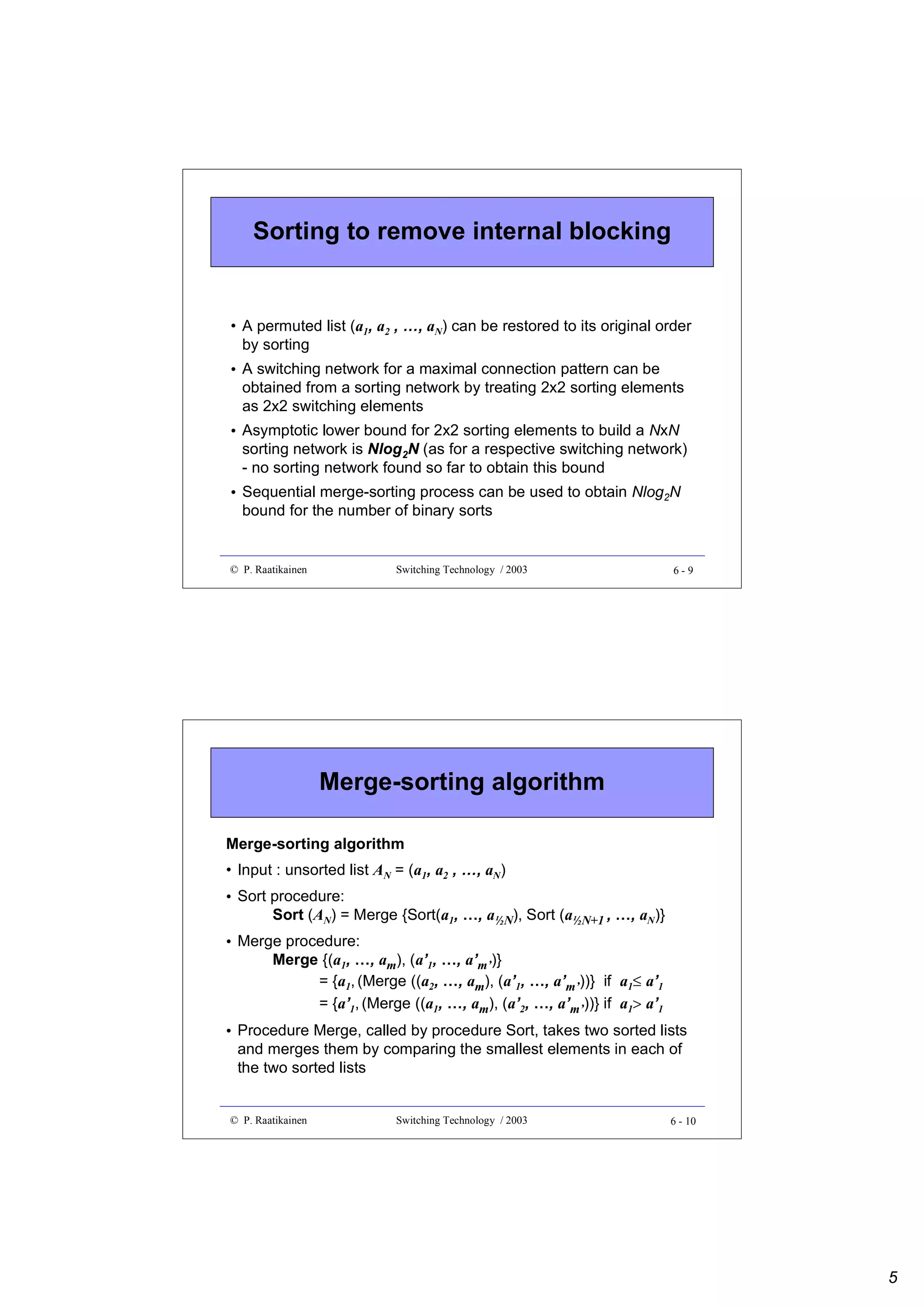

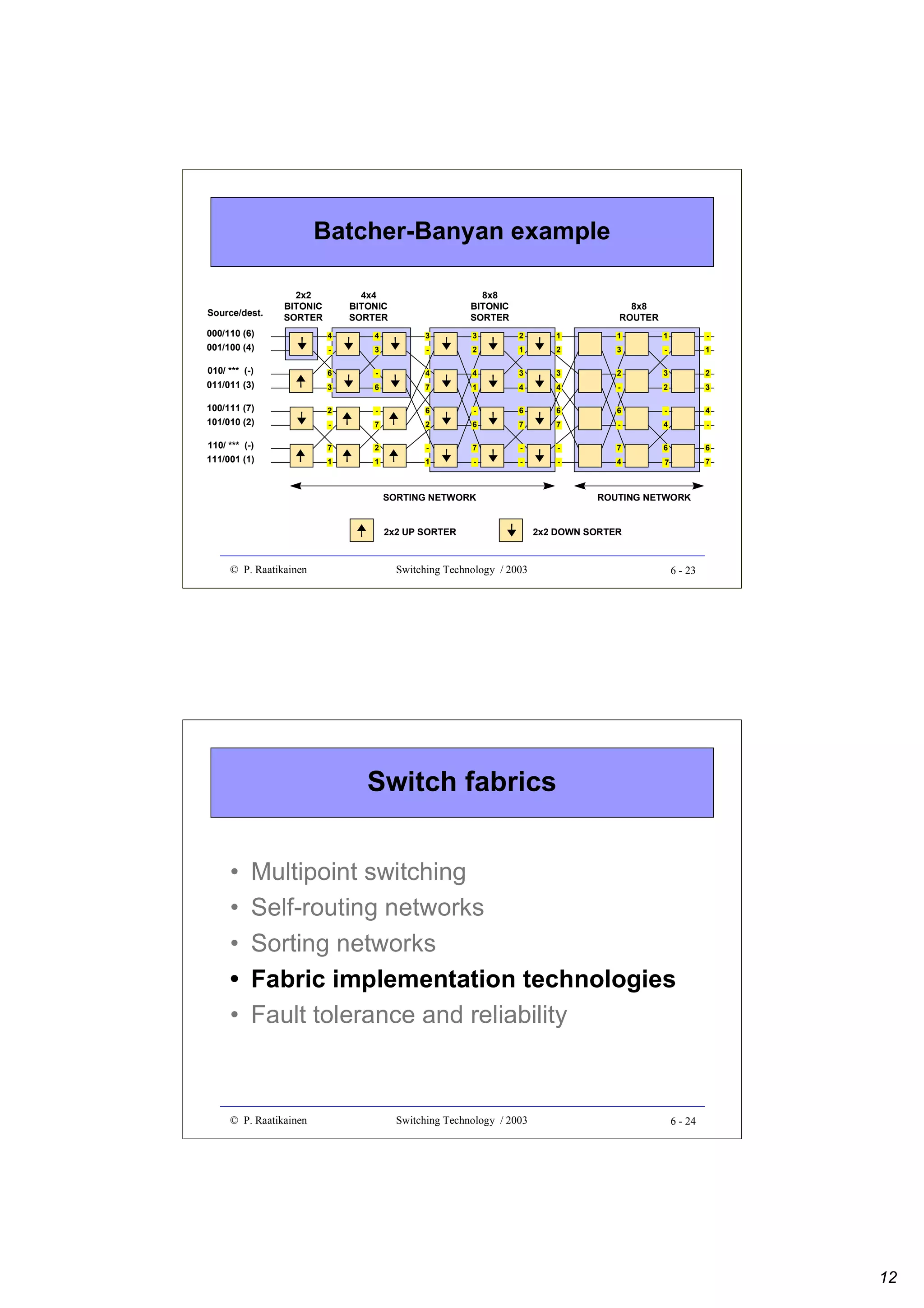

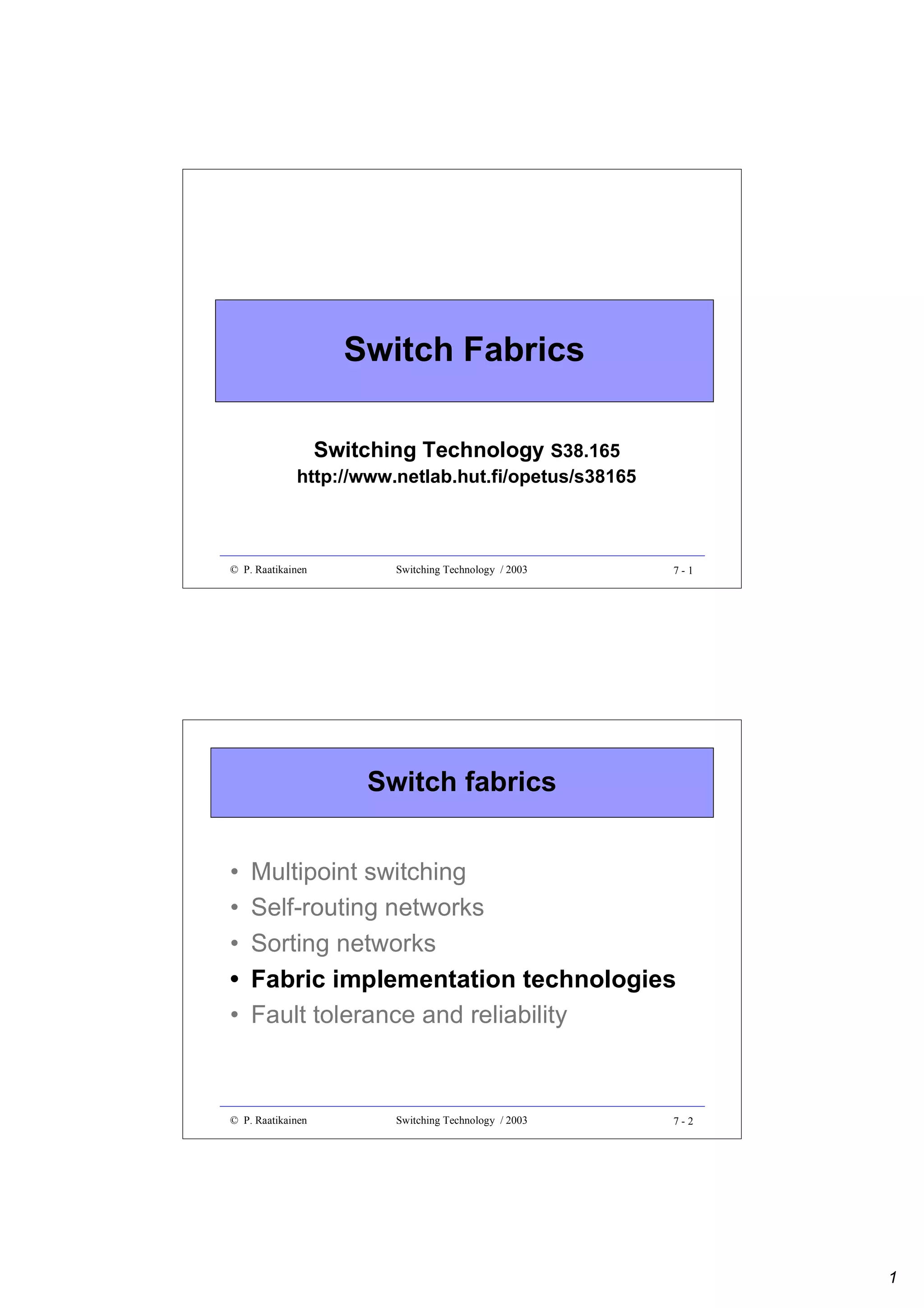

![Design optimization example (cont.)

• As an example, let’s assume that price of each component is a function of

time and is given by P(t)=Ce-t/T+ D ,

where C, D and T are component specific constants

=> Pa(t)=Cae-t/Ta+ Da , Pb(t)=Cbe-t/Tb+ Db and Pc(t)=Cce-t/Tc+ Dc

• Number of alternative crossbar components needed to build an NxN switch

=> Ka = ceil[N/Na]2, Kb = ceil[N/Nb]2 , Kc = ceil[N/Nc]2

• Alternative component costs as a function of time t

=> Pa(t)=Cae-(t- ta)/Ta+ Ca

=> Pb(t)=Cbe-(t- tb)/Tb+ Cb

=> Pc(t)=Cce-(t- tc)/Tc+ Cc

• These functions can be used to draw price development curves to make

comparisons

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

6 - 51

Design optimization example (cont.)

Numerical example:

• Let N = 64, Na = 16, Nb = 32, Nc = 64, Ta = Tb = Tc = 3 time units (years),

Ca = 20,Cb = 50, Cc = 100 and Da = 10, Db = 20, Dc = 40 price units (euros)

• Product development period is assumed to be 1 time unit (year) and

tb = ta +1.5, tc = ta +3, tm = ta +4 => tpd = ta + 3

• Choosing that tpd = to = 0 => ta = t + 3, tb = t +1.5, tc = t, tm = t -1 (t ≥ tpd = 0 )

• Number of components needed Ka = 16, Kb = 4, Kc = 1

• Switch fabric component cost functions

=> Pa(t)=16[20e-(t+3)/3 + 10]

=> Pb(t)=4[50e-(t+1.5)/3 + 20]

=> Pc(t)=100e-(t)/3 + 40

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

6 - 52

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-154-2048.jpg)

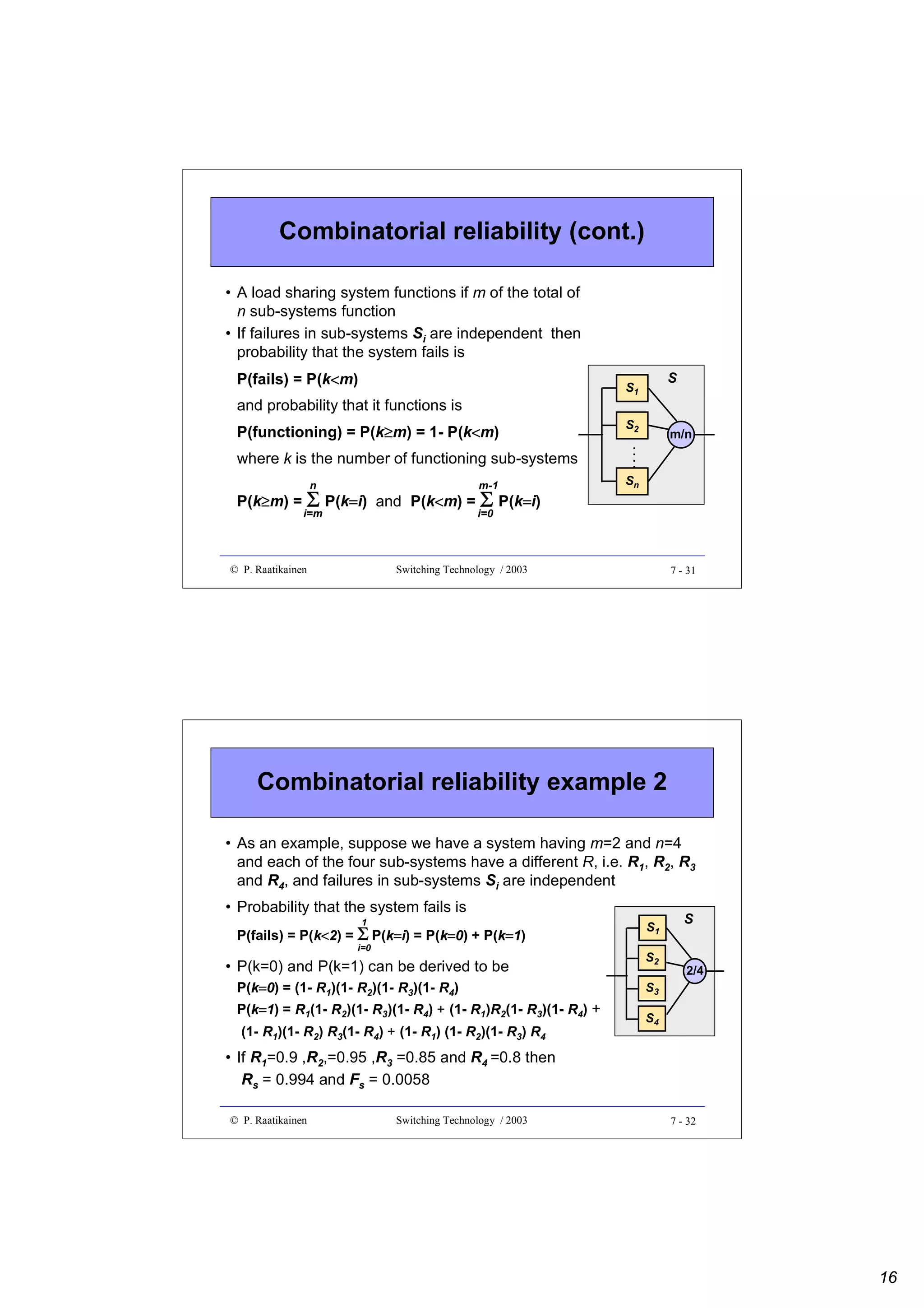

![Combinatorial reliability

• A serial system S functions if and only if all

its parts Si (1≤i≤n) function

S

n

=> Rs = Π Ri and Fs = (1- Rs)

S1

i=1

S2

Sn

• Failures in sub-systems are supposed to be

independent

S1

• A parallel (replicated) system fails if all its subsystems fail

n

=> Fs = Π (1-Ri)

i=1

S2

n

and Rs = 1- Fs = 1- Π (1-Ri)

i=1

Sn

• Reliability of a duplicated system (Ri = R) is

Rs = 1- (1-R)2

© P. Raatikainen

S

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 29

Combinatorial reliability example 1

• Calculate reliability Rs and failure probability Fs of system S

given that failures in sub-systems Si are independent and for

some time interval it holds that

R1 = 0.90, R2 = 0.95 and R3 = R4 = 0.80

=> Rs = Π Ri = R1 x R2 x R3-4

=> R3-4 = 1- Π (1-Ri) = 1- (1- R3)(1- R4)

=> Rs = R1 x R2 x [1- (1- R3)(1- R4)]

S

S1

S3-4

S3

S2

S4

=> Fs = 1- Rs = 1 - R1 x R2 x [1- (1- R3)(1- R4)]

=> Rs = 0.82 and Fs = 0.18

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 30

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-170-2048.jpg)

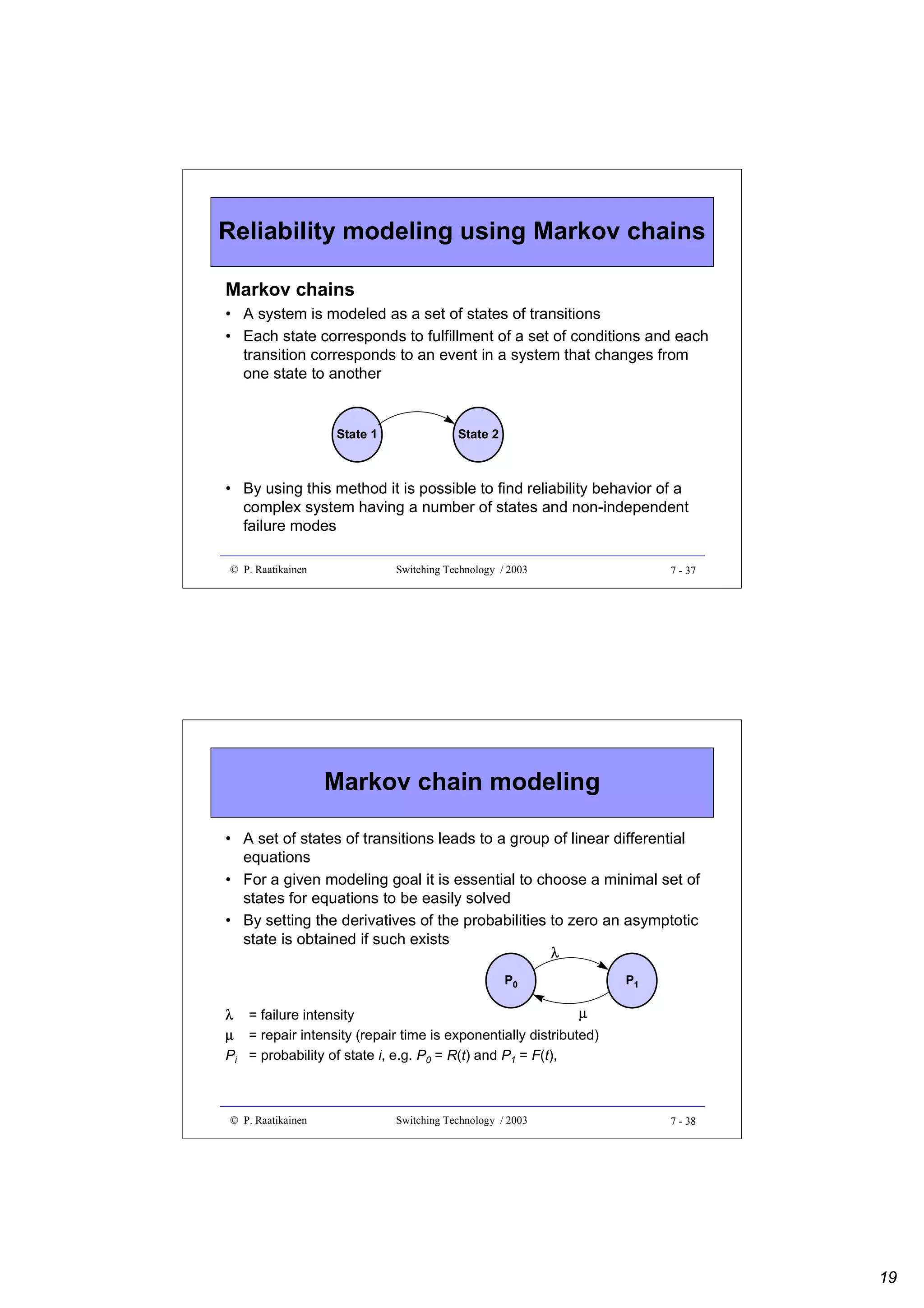

![Combinatorial reliability (cont.)

• If failures in sub-systems Si of an m/n system

are independent and Ri = R for all i∈[1,n]

then the system is a Bernoulli system and

binomial distribution applies

n

=> Rs =

Σ ( k )Rk(1-R)n-k

k=m

n

• For a system of m/n = 2/3

3

3!

−−−−

=> R2/3 = Σ k!(3-k)! Rk(1-R)3-k = 3R2 - 2R3

k=2

If for example R

S1

S2

S

m/n

Sn

= 0.9 => R2/3 = 0.972

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 33

Computing MTTF

• MTTF =

∞

∫ R(t)dt - valid for any reliability distribution

0

• Single component with a constant failure rate (CFR) λ

- R(t) = e-λt

- MTTF = 1/λ

λ

• Serial systems with n CFR components

- Rs(t) = R1(t) x R2(t) x ... x Rn(t) = e- (λ1 + λ2 + ... + λn)t = e- λst

- λs= λ1 + λ2 + ... + λn

• MTTFs = 1/ λs

• 1/MTTFs = 1/MTTF1 + 1/MTTF2 + ... + 1/MTTFn

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 34

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-172-2048.jpg)

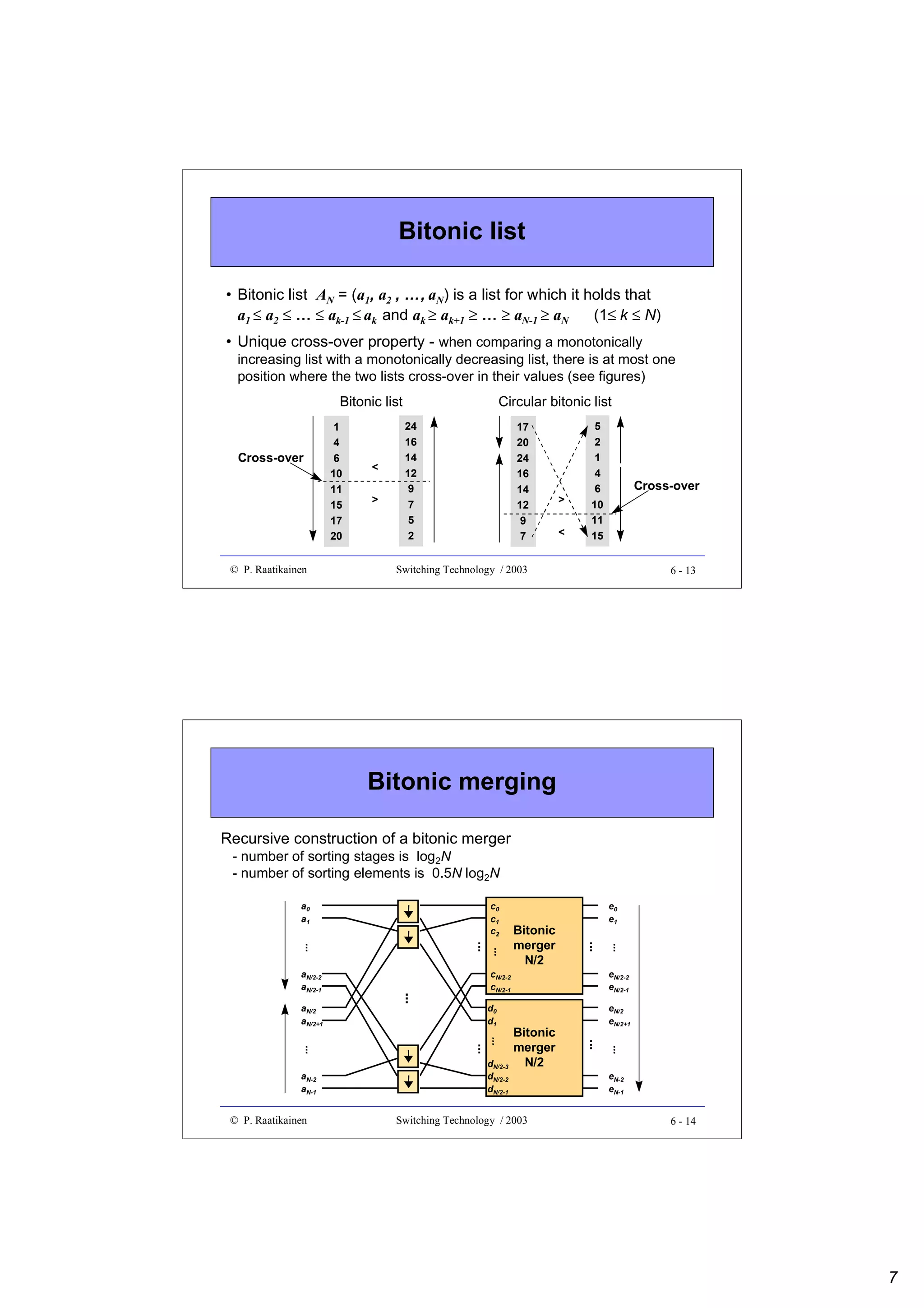

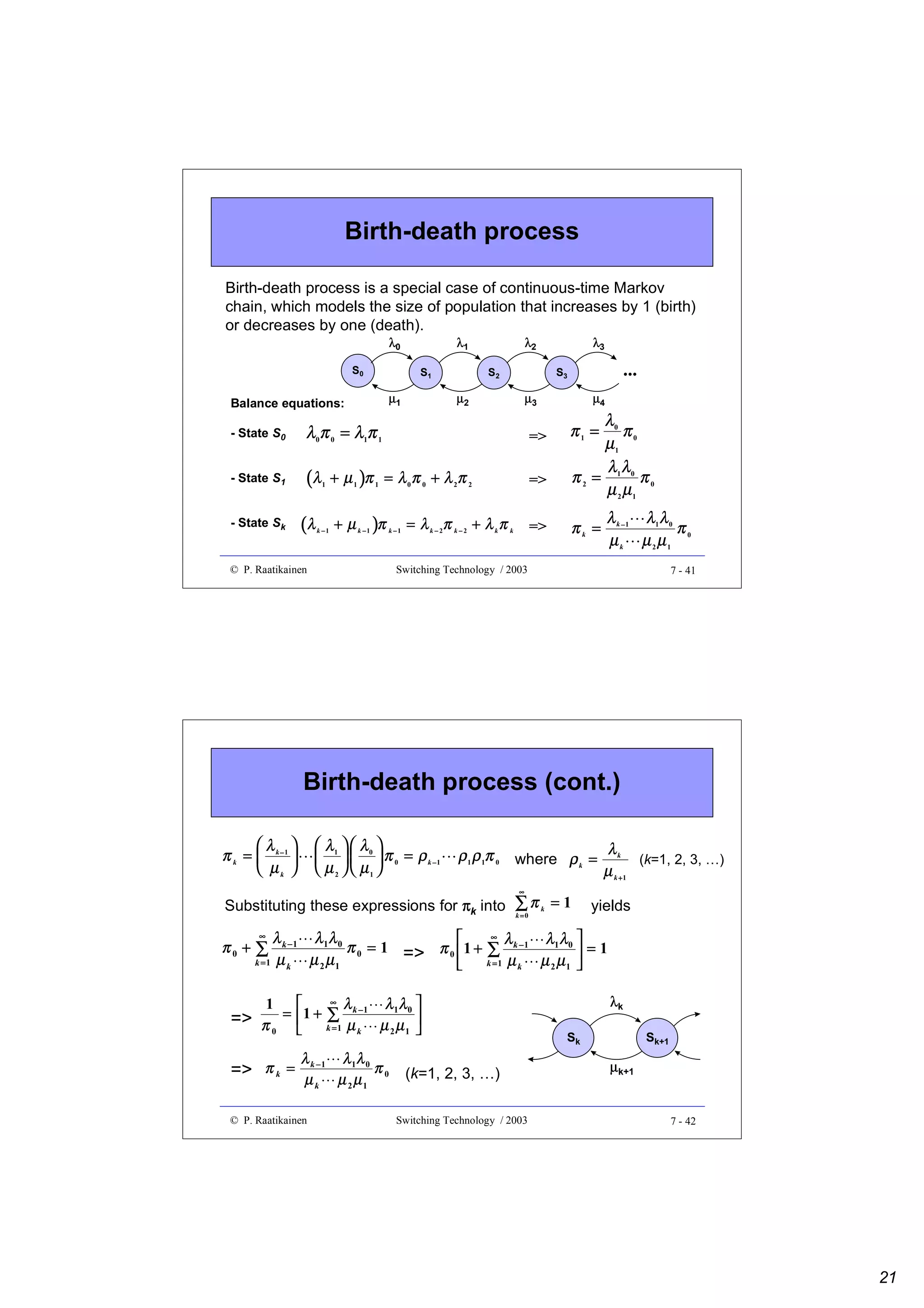

![Telecom exchange reliability from

subscriber’s point of view

n-1/n

Line-card

Subscriber

module

control

Subscriber

call

control

Centralized

functions

Exchange

terminal

CCS7 signaling processors

• (n-1)/n operational processors

for call setup

• chosen processor functions

during a call

Premature release requirement P ≤ 2x10-5 applied

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 35

Failure intensity

• Unit of failure intensity λ is defined to be

λ

[λ] = fit = number of faults /109 h

• Failure intensities for replaceable plug-in-units varies in the

range 0.1 - 10 kfit

• Example:

• if failure intensity of a line-card in an exchange is 2 kfit, what

is its MTTF ?

109 h

1 000 000 h

MTTF = 1/λ = = = 58 years

λ 2000

2x24x360

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 36

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-173-2048.jpg)

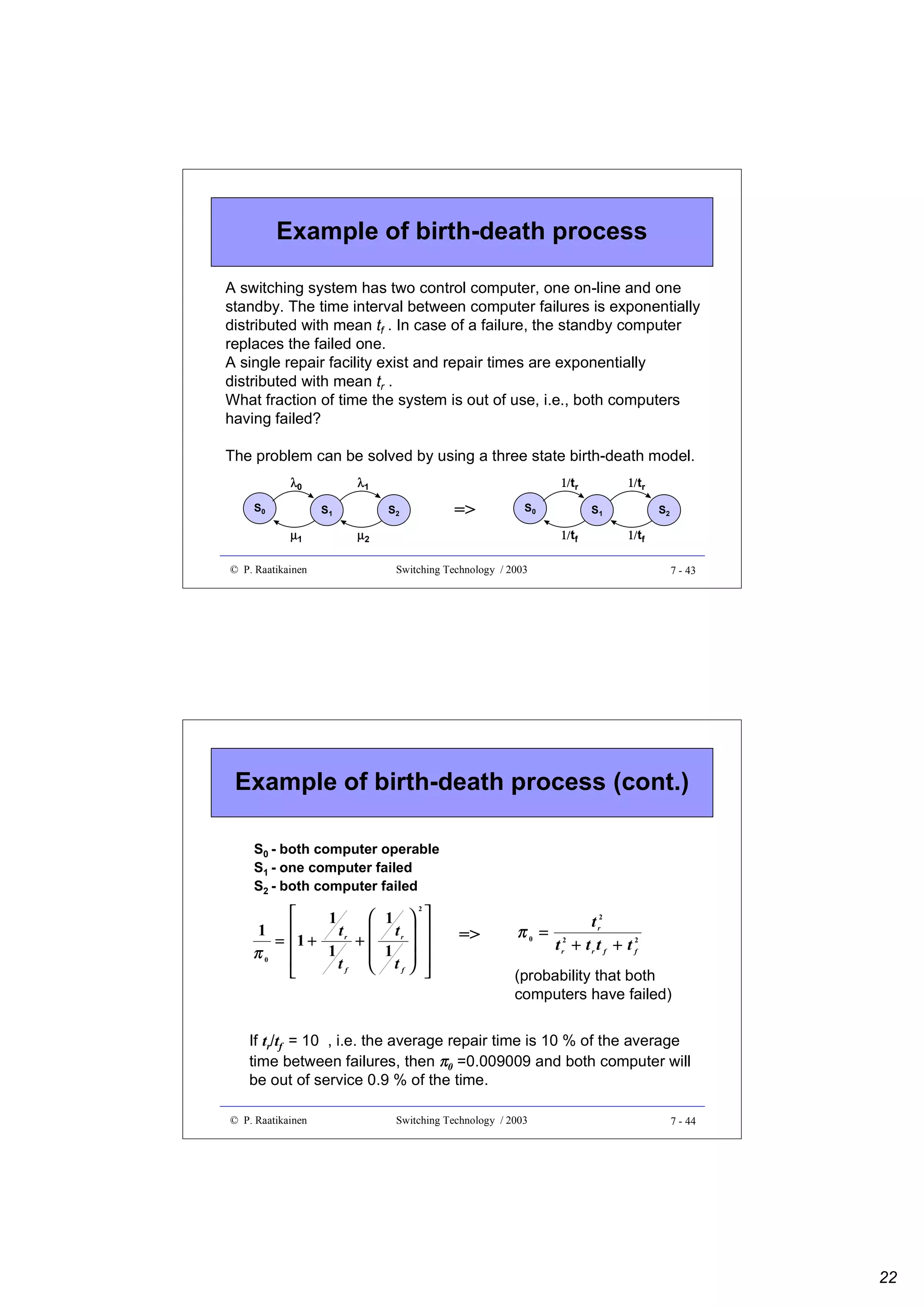

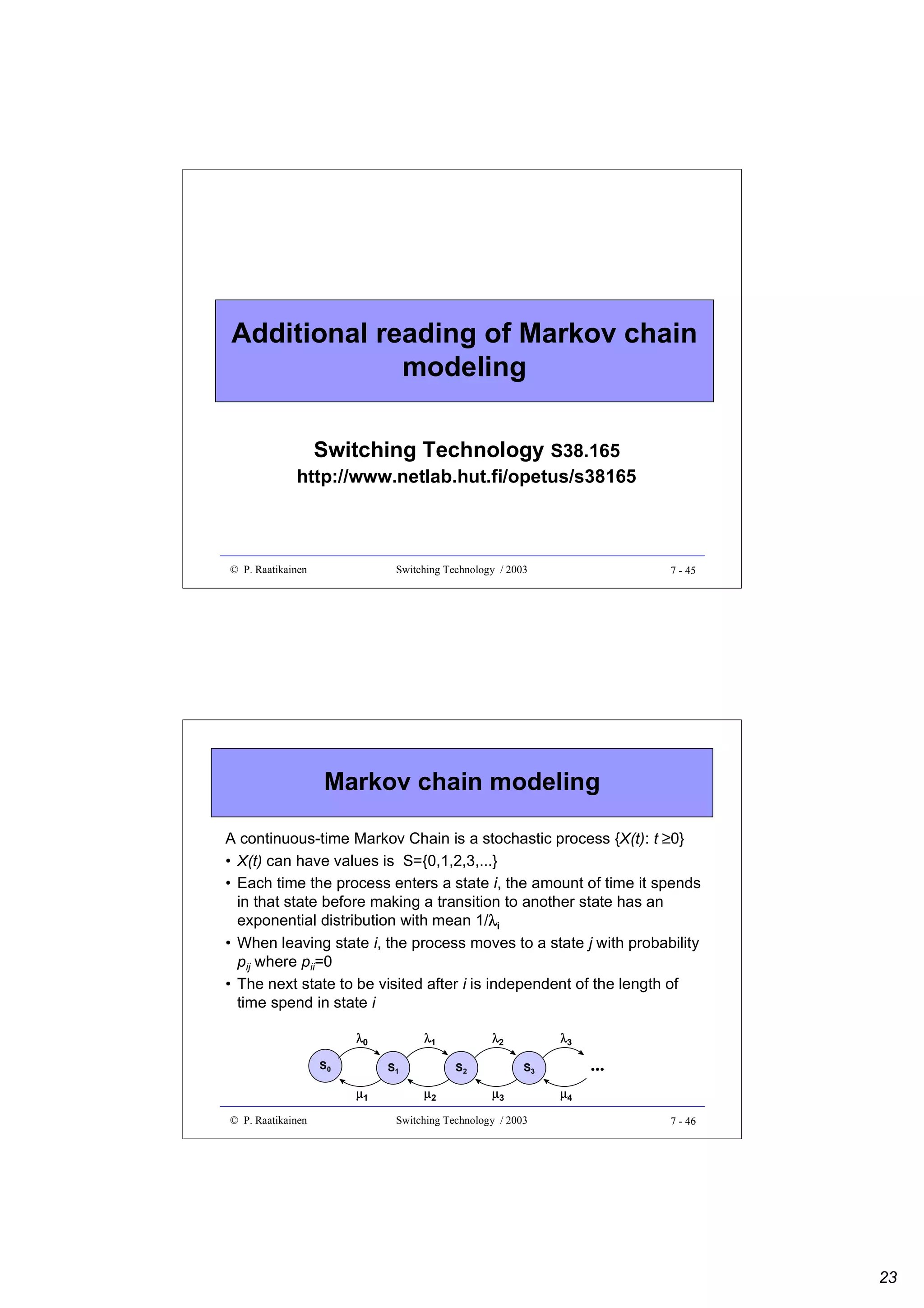

![Markov chain modeling (cont.)

• Probabilities (πi) of the states and transition rates (λij) between the

states are tied together with the following formula

πΛ = 0

where

π n]

)

¡

¡

¢

¡

¡

© P. Raatikainen

)

λ13

λ23

− (λ31 + λ32 +

¢

λ12

− (λ21 + λ23 +

λ32

¢

)

¢

¢

− (λ12 + λ13 +

λ21

Λ=

λ31

¢

π = [π 1 π 2

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 39

Markov chain modeling (cont.)

Example

λ12

λ13

− (λ12 + λ13 )

Λ=

− (λ21 + λ23 )

λ21

λ23

− (λ31 + λ32 )

λ31

λ32

and π = [π 1 π 2

£

πΛ = 0

πn]

− (λ12 + λ13 )π 1 + λ12π 2 + λ13π 3 = 0

λ21π 1 − (λ21 + λ23 )π 2 + λ23π 3 = 0

λ π + λ π − (λ + λ )π = 0

32 2

31

32

3

31 1

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

λ12

S1

λ31

S2

λ21

λ13

λ32

λ23

S3

7 - 40

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-175-2048.jpg)

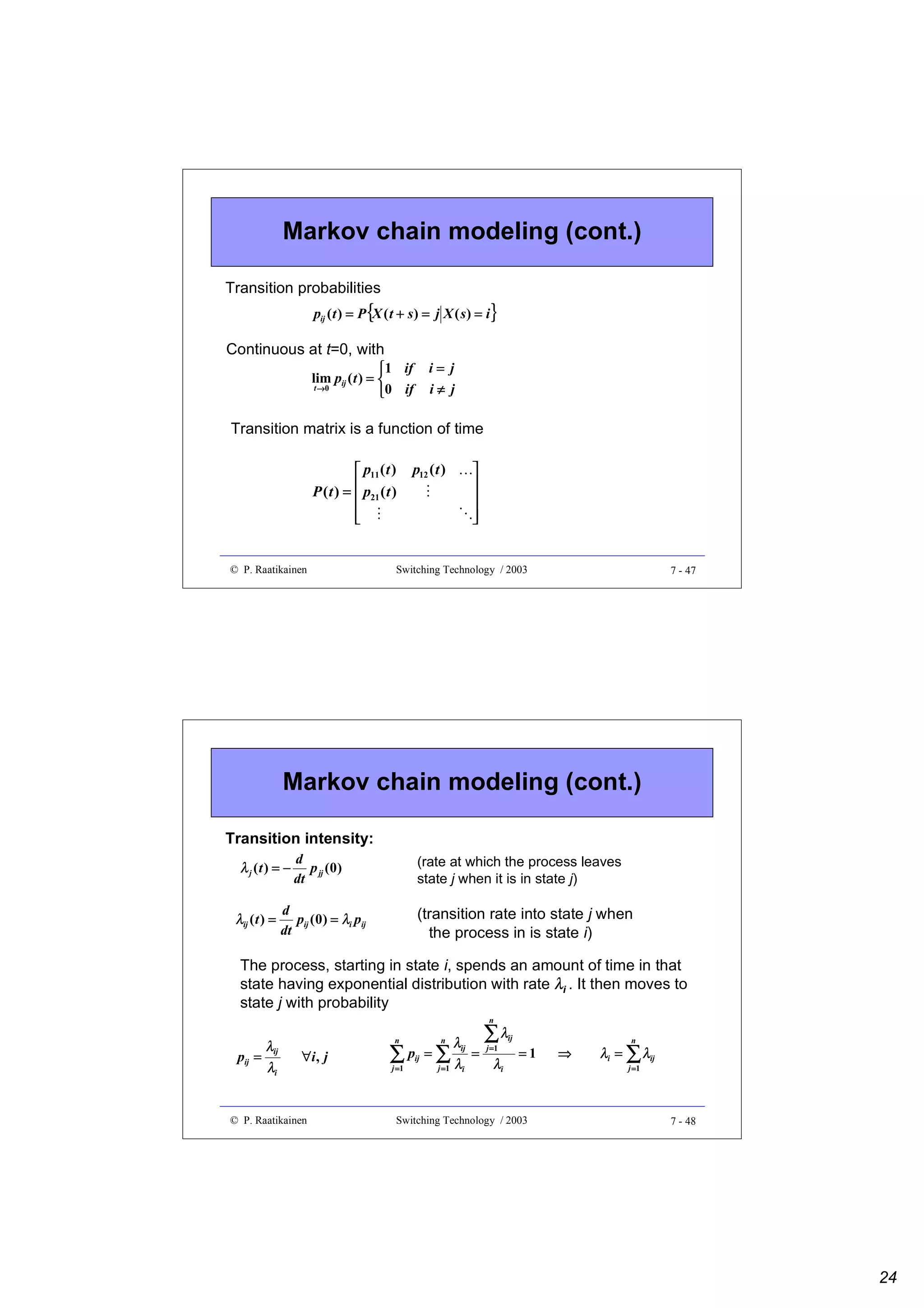

![Markov chain modeling (cont.)

Chapman-Kolmogorov equations:

∀i , j ∈ S

pij ( t + s ) = ∑ pik ( t ) pkj ( s )

∀s , t ≥ 0

k∈S

Since p(t) is a continuous function

d

pij ( ∆t ) = pij (0 ) + pij ( 0) ∆t + o( ∆t 2 )

dt

d

λij ( t ) = pij (0 )

We have defined =>

dt

≠

For i≠j:

pij ( ∆t ) = pij (0 ) + λij ∆t + o( ∆t 2 ) ≈ λij ∆t

(for small ∆t)

For i=j:

pii ( ∆t ) = pii (0 ) + λii ∆t + o( ∆t 2 ) ≈ 1 + λii ∆t

(for small ∆t)

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 49

Markov chain modeling (cont.)

From Chapman-Kolmogorov equations:

pij ( t + ∆t ) = ∑ pik ( t ) pkj ( ∆t ) = pij ( t ) p jj ( ∆t ) + ∑ pik ( t ) pkj ( ∆t )

k≠ j

k

[

]

[

= pij ( t ) 1 + λ jj ∆t + o( ∆t ) + ∑ pik ( t ) λkj ∆t + o( ∆t 2 )

2

k≠ j

]

pij ( t + ∆t ) = pij ( t ) + ∑ pik ( t )λkj ∆t + ∑ pik ( t ) o( ∆t 2 )

k

k

pij ( t + ∆t ) − pij ( t )

∆t

o( ∆ t 2 )

= ∑ pik ( t )λkj + ∑ pik ( t )

k

k

∆t

Taking the limit as ∆t → 0

© P. Raatikainen

d

pij ( t ) = ∑ pik ( t )λkj

dt

k

Switching Technology / 2003

∀i , j

7 - 50

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-180-2048.jpg)

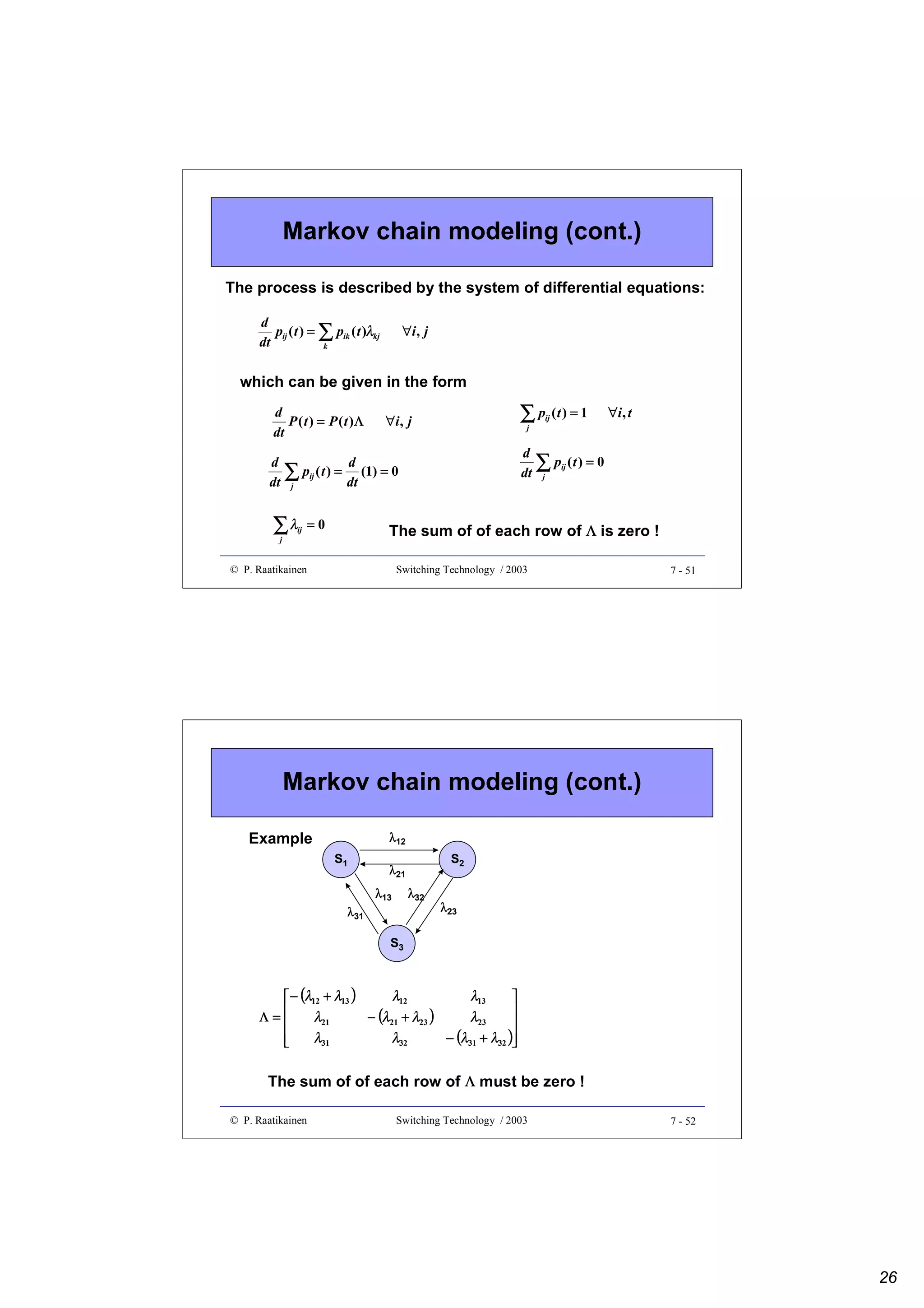

![Markov chain modeling (cont.)

An alternative derivation of the steady-state conditions begins with

the differential equation describing the process:

d

pij ( t ) = ∑ pik ( t )λkj

dt

k

∀i , j

Suppose that we take the limit of each side as t → ∞

d

pij (t ) = lim ∑ pik (t )λkj

t →∞

dt

k

=>

lim

=>

d

lim pij (t ) = ∑ lim pik (t )λkj

t →∞

dt t →∞

k

=>

∑π

t →∞

k

λkj = 0

i.e. πΛ=0

k

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 55

Markov chain modeling (cont.)

Example

λ12

λ13

− (λ12 + λ13 )

Λ=

− (λ21 + λ23 )

λ21

λ23

− (λ31 + λ32 )

λ31

λ32

and π = [π 1 π 2

πΛ = 0

πn]

λ12

S1

λ31

S2

λ21

λ13

λ32

λ23

S3

− (λ12 + λ13 )π 1 + λ21π 2 + λ31π 3 = 0

λ12π 1 − (λ21 + λ23 )π 2 + λ32π 3 = 0

λ π + λ π − (λ + λ )π = 0

23 2

31

32

3

13 1

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

7 - 56

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-183-2048.jpg)

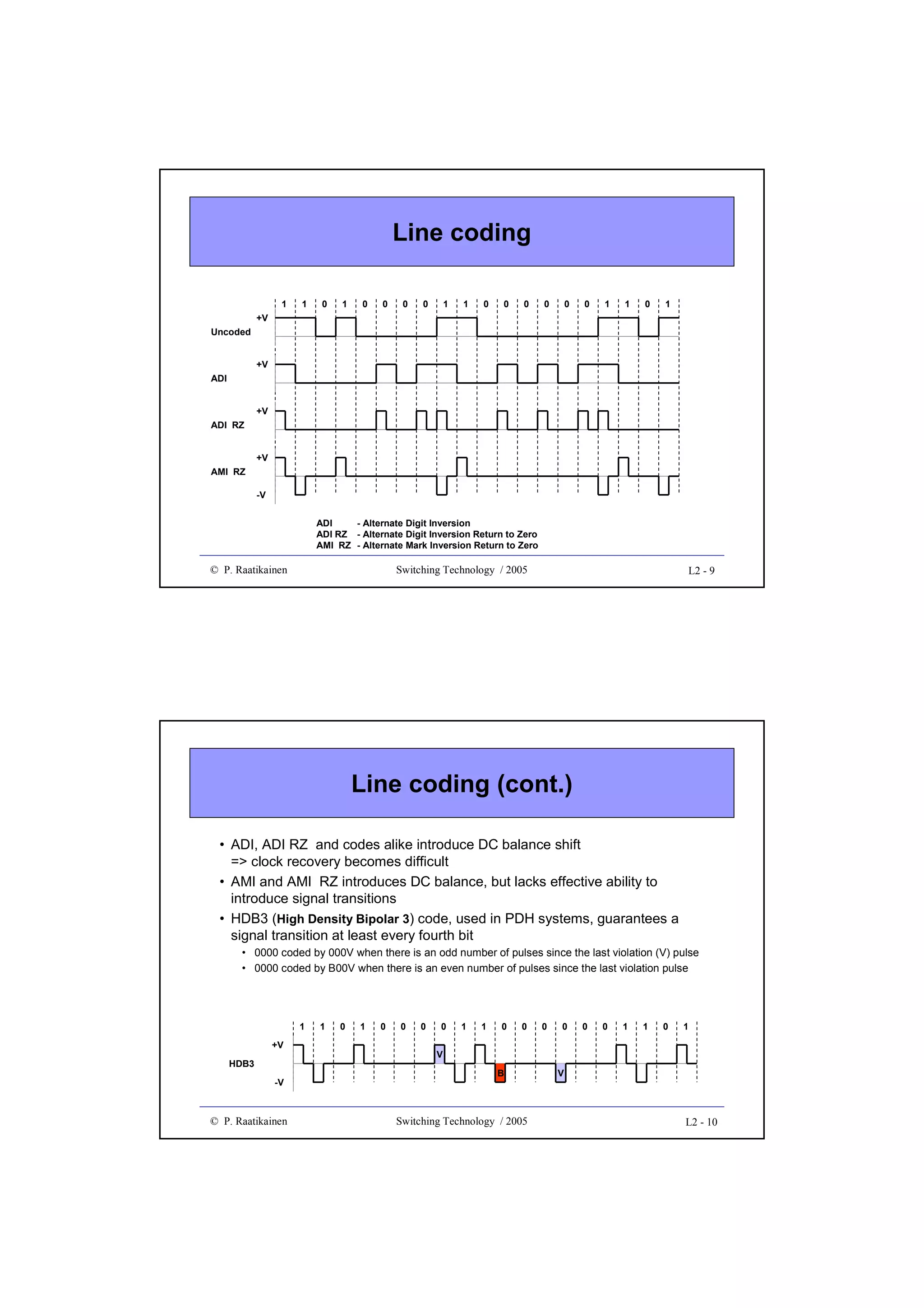

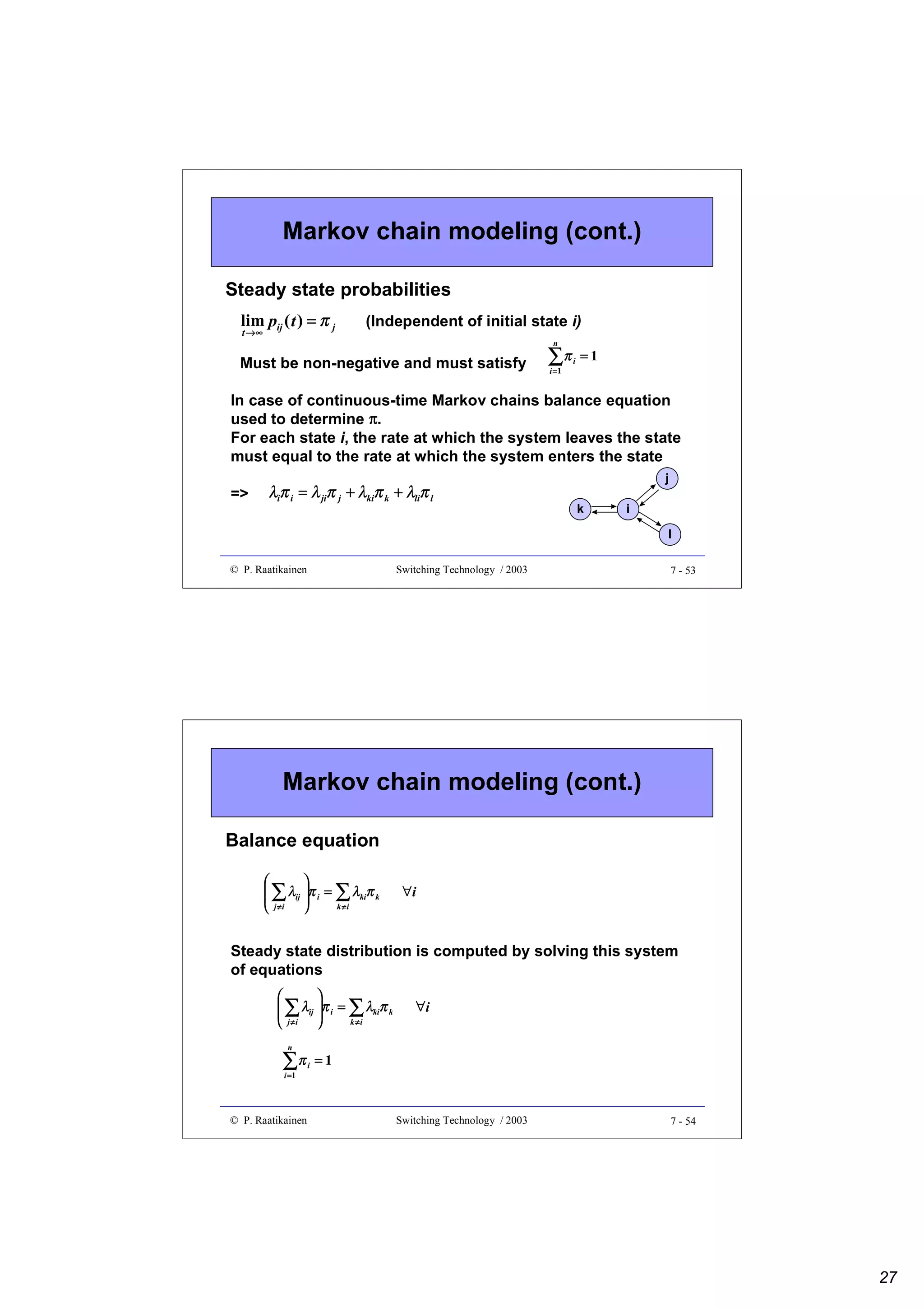

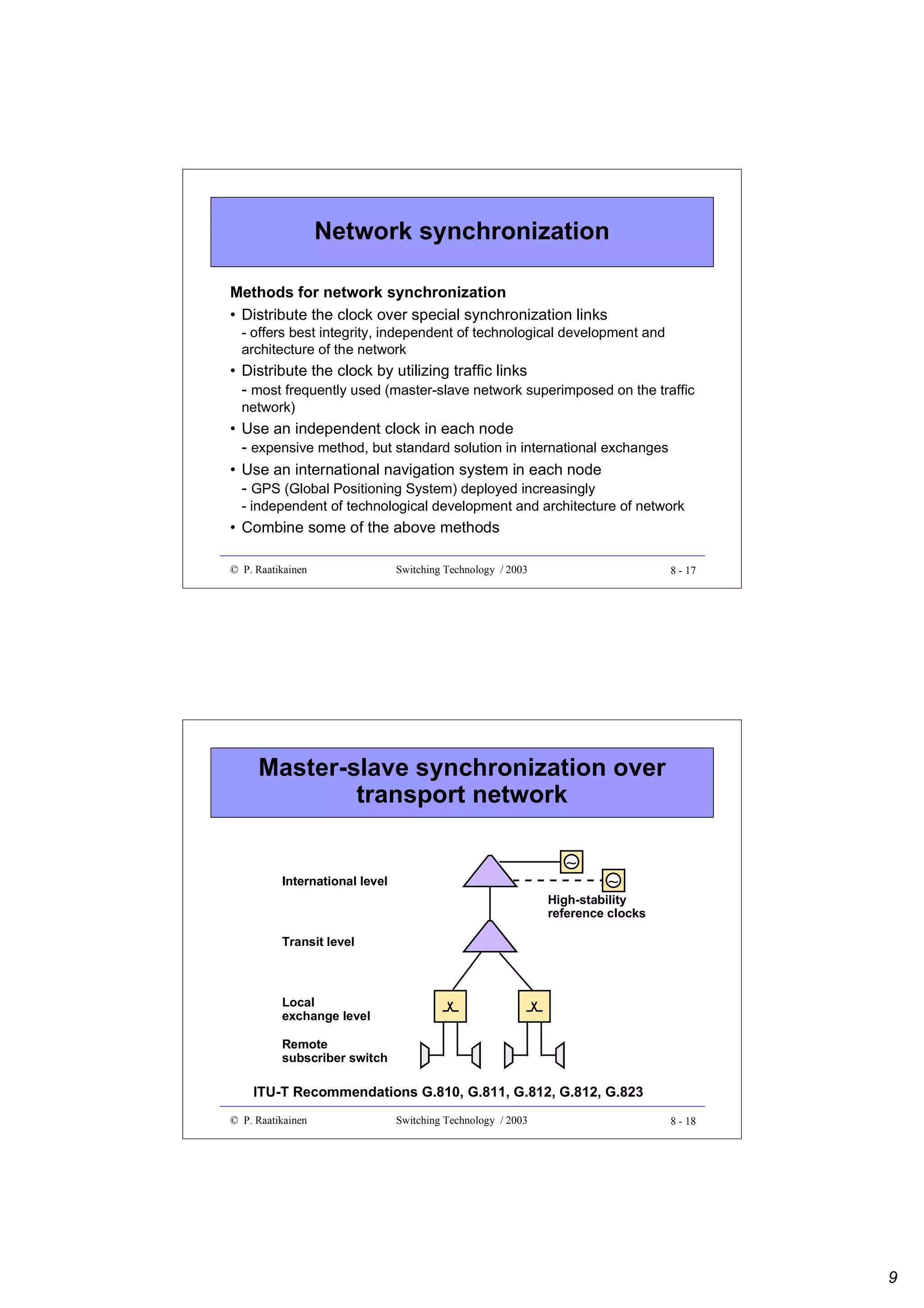

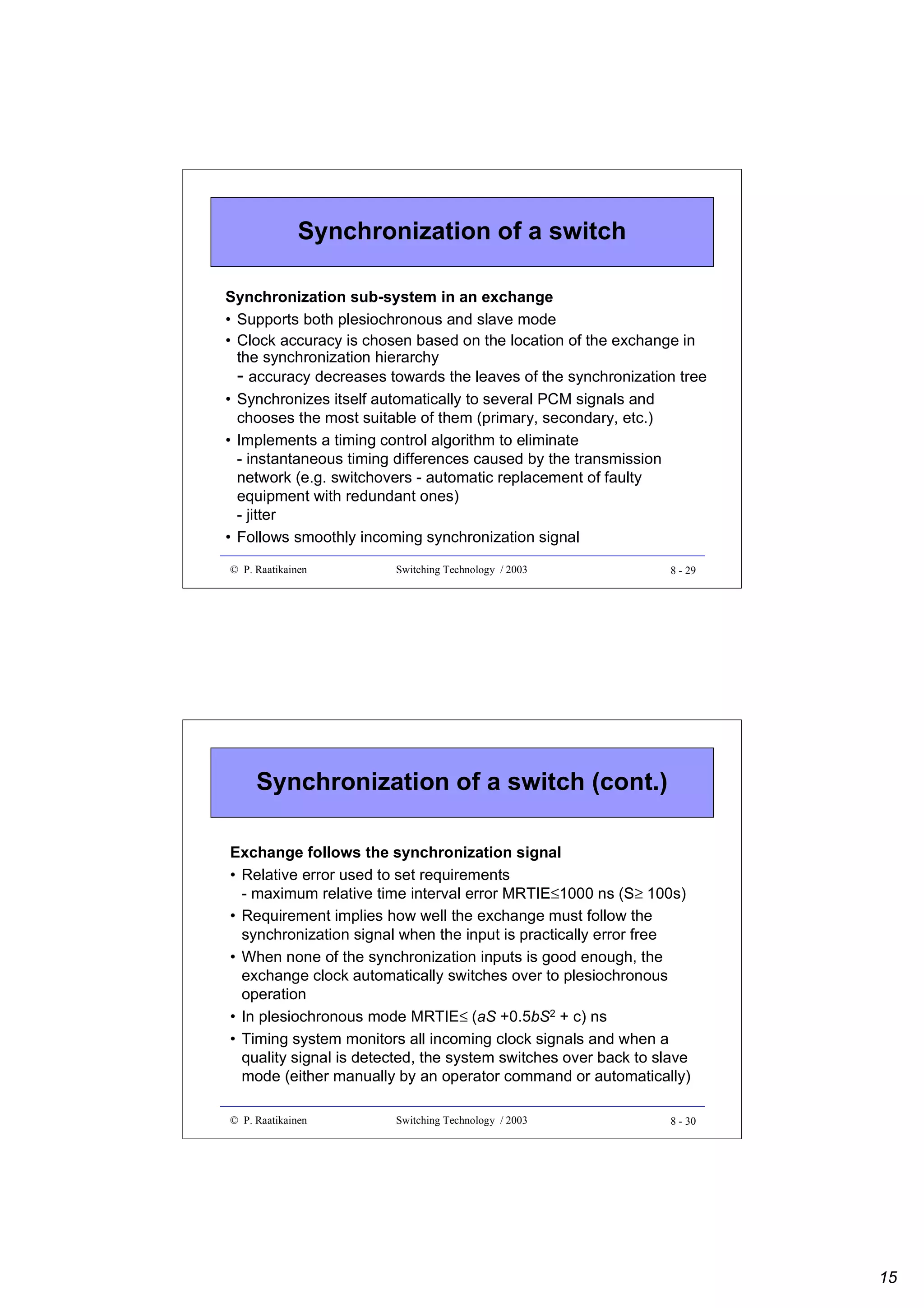

![MTIE limits for PRC, SSU and SEC

Clock

source

Time-slot

interval [ns]

Time-slot

interval [ns]

PRC

25 ns

0.3t ns

300 ns

0.01t ns

0.1 < t < 83 s

83 < t < 1000 s

1000 < t < 30 000 s

t > 30 000 s

SSU

25 ns

10t ns

2000 ns

433t0.2 + 0.01t ns

0.1 < t < 2.5 s

2.5 < t < 200 s

200 < t < 2 000 s

t > 2 000 s

SEC

250 ns

100t ns

2000 ns

433t0.2 + 0.01t ns

0.1 < t < 2.5 s

2.5 < t < 20 s

20 < t < 2 000 s

t > 2 000 s

ETS 300 462-3

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

8 - 25

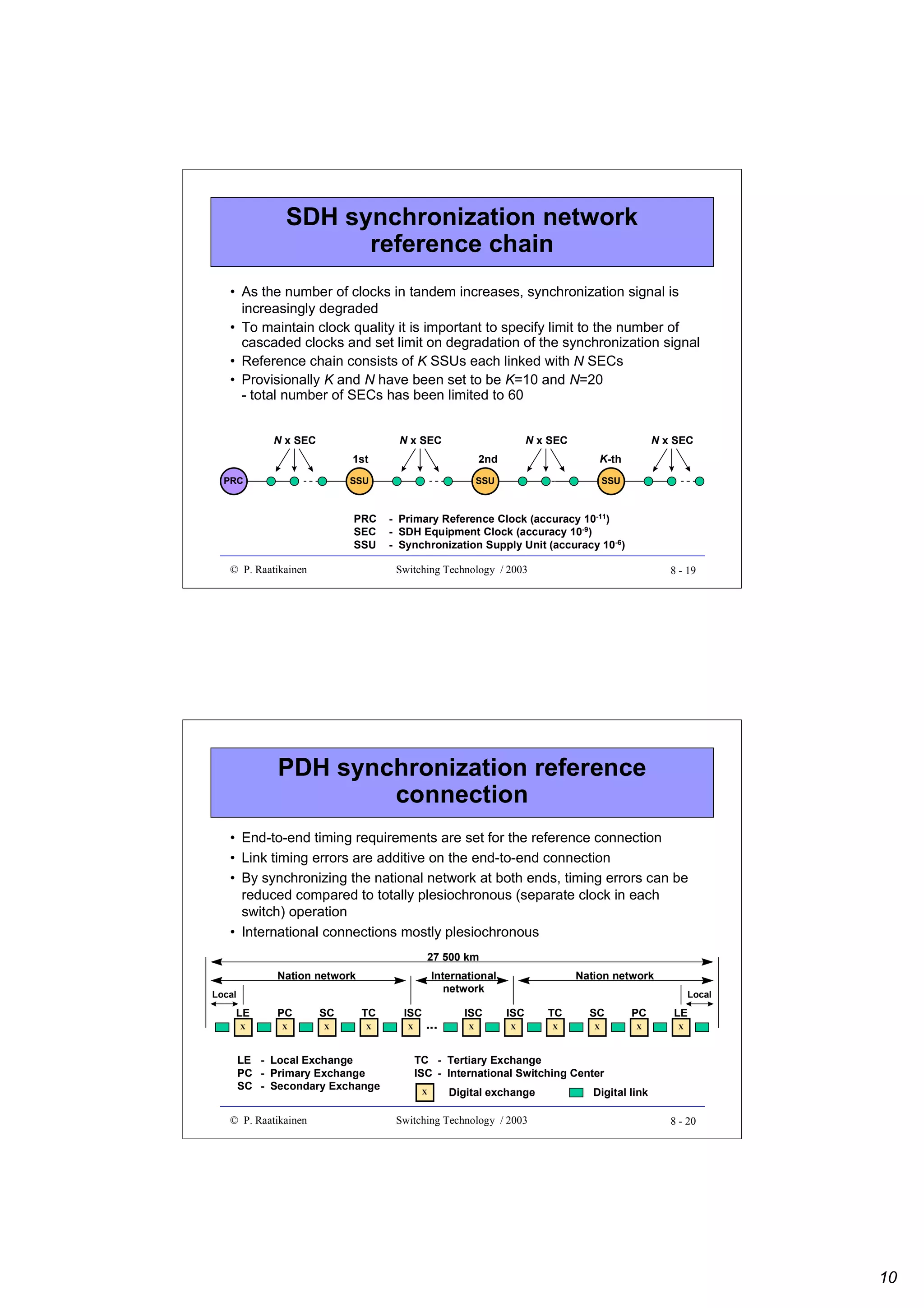

Occurrence of slips

• Slips occur on connections whose timing differs from the timing signal used by

the exchange

• If both ends of a connection are internally synchronized to a PRC signal,

theoretically slips occur no more frequently than once in 72 days

• In a reference connection a slip occurs theoretically once in 72/12 = 6 days

or if national segments are synchronized once in 720/4 = 18 days

• Slip requirement on an end-to-end connection is looser:

Average frequency of slips

Share of time during one year

≤ 5 slips / 24h

98.90 %

5 slips/ 24 h …. 30 slips/ 1h

<1%

≤ 10 slips / 1h

< 0.1 %

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

8 - 26

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-196-2048.jpg)

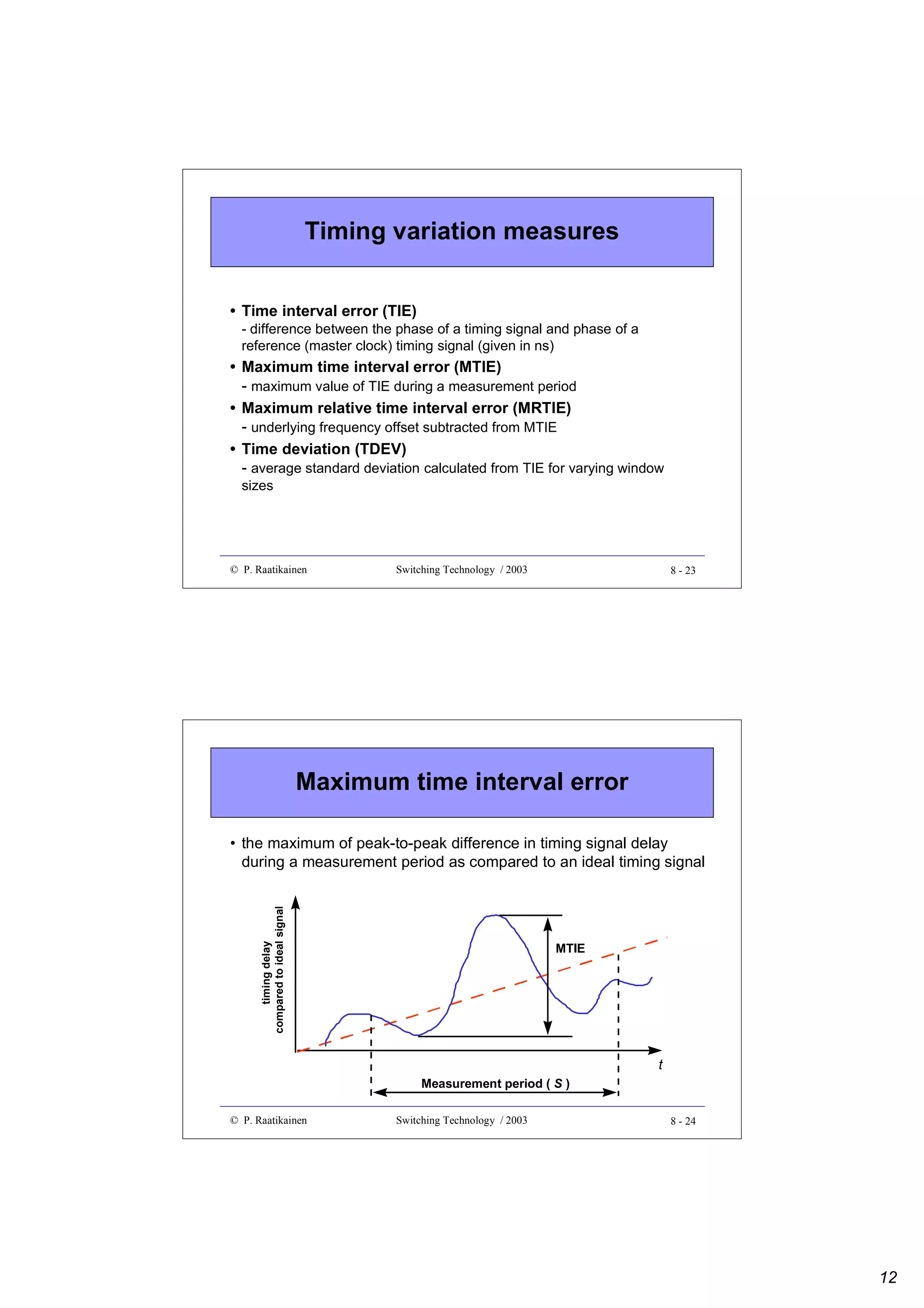

![Slip calculation example

Show that two networks with single frame buffers and timed from

separate PRCs would see a maximum slip rate of one slip every

72 days

Solution:

• Timing accuracy of a PRC clock is 10-11

• Let the frequencies of the two ends be f1 and f2

• In the worst case, these frequencies deviate from the reference

clock fo by 10-11x fo and those deviations are to different directions

• Let the frequencies be f1 = (1+ 10-11) fo and f2 = (1- 10-11) fo

• Duration of bits in these networks are T1= 1/ f1 and T2= 1/ f2

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

8 - 27

Slip calculation example (cont.)

Solution (cont.):

• During one bit interval, the timing difference is T1- T2 and after

some N bits the difference exceeds a frame length of 125 µs and a

slip occurs => NT1- T2 = 125x10-9

-9 /[(1/ f -1/ f ) ]

=> N = 125x10

1

2

• Inserting f1 = (1+ 10-11) fo and f2 = (1- 10-11) fo into the above equation,

we get => N = 125x10-9 fo (1- 10-22)/(2x 10-11)

• Multiplying N by the duration (Tb) of one bit , we get the time (Tslip)

between slips

• In case of E1 links, fo= 2.048x106/s and Tb = 488 ns. Dividing the

obtained Tslip by 60 (s), then by 60 (min) and finally by 24 (h) we get

the average time interval between successive slips to be 72.3 days

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

8 - 28

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-197-2048.jpg)

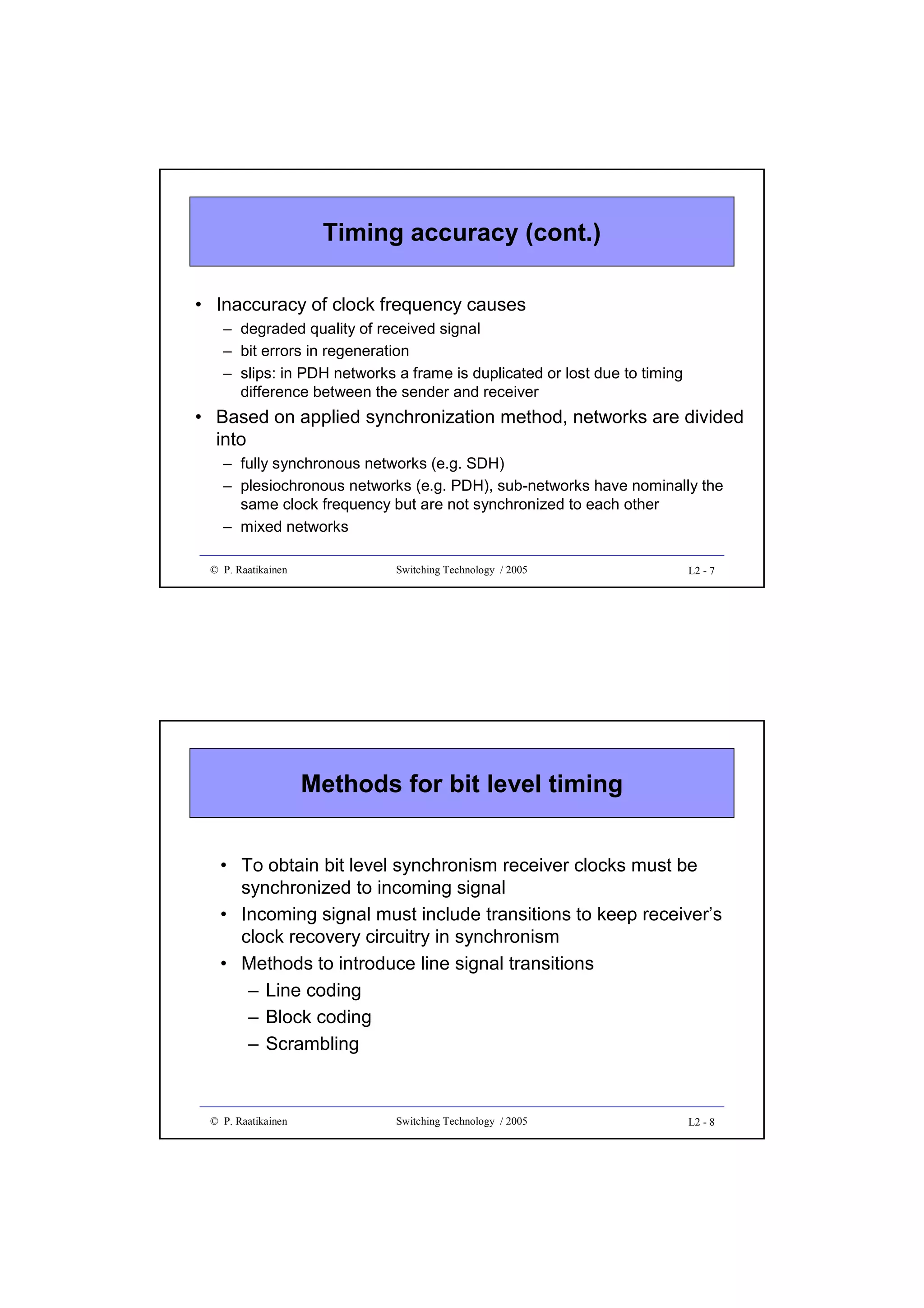

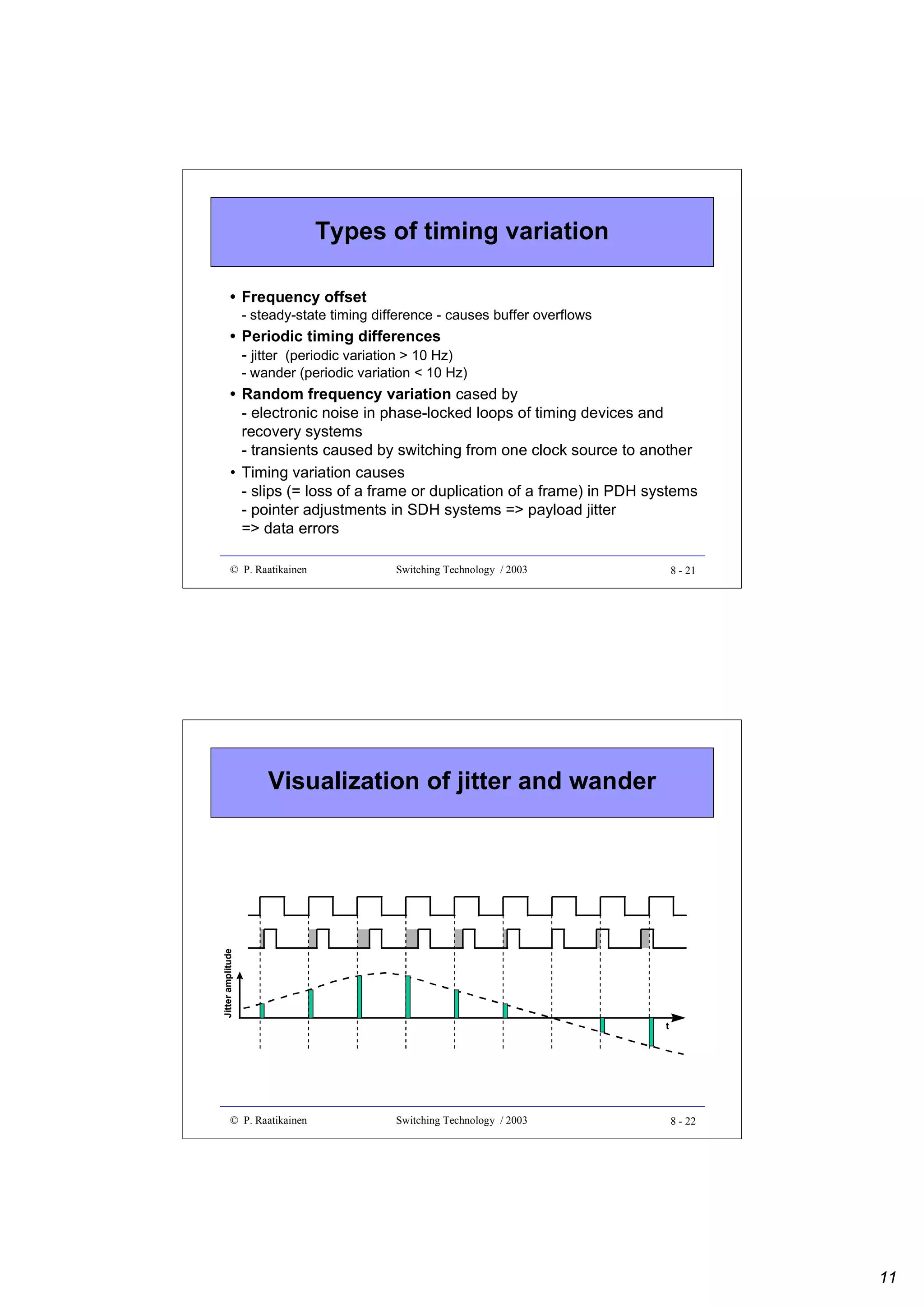

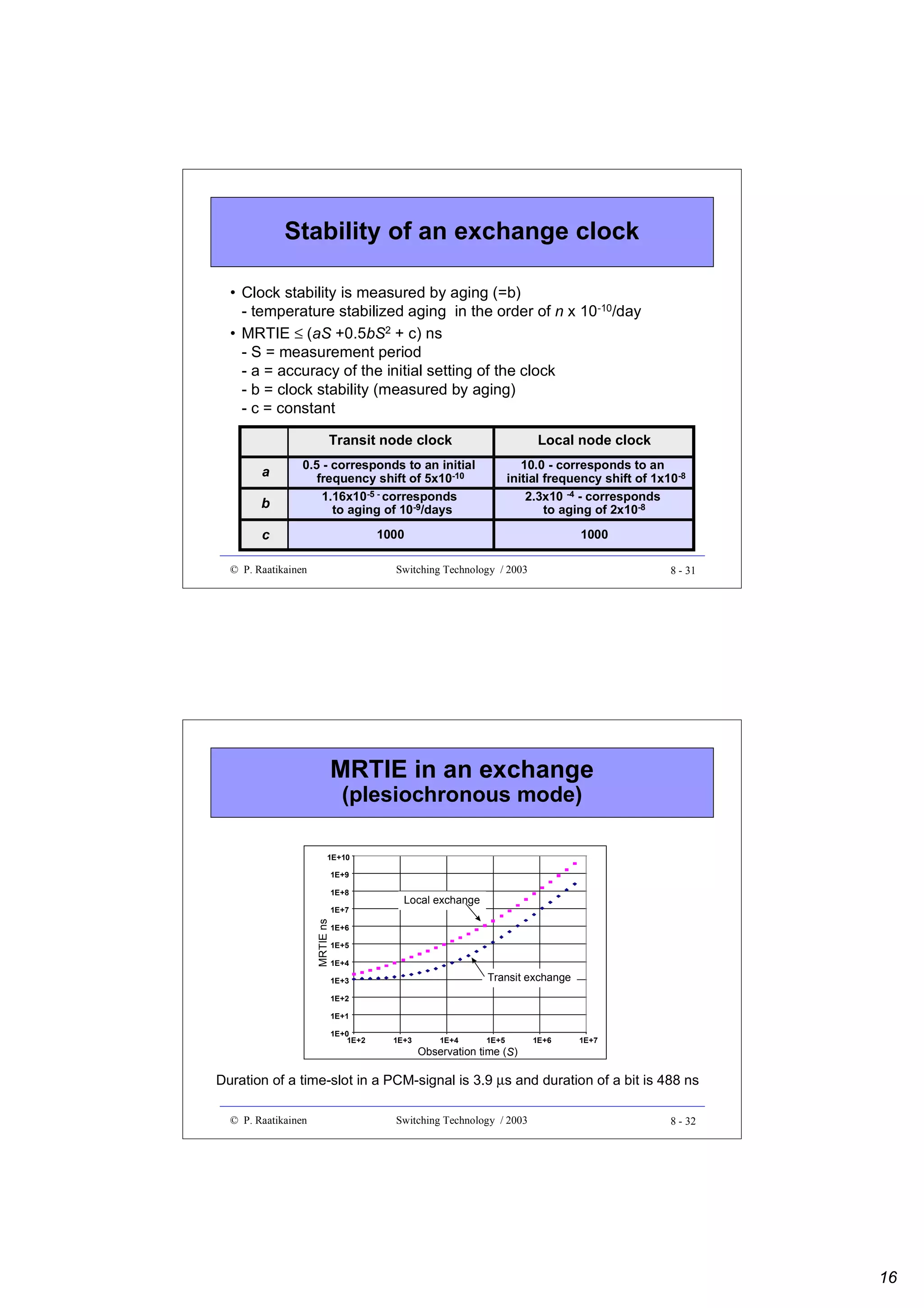

![PDH bit rates and related bit/octet times

Hierarchy

level

Time-slot

Bit interval

interval [ns]

[ns]

E1/2M

3906

488

E2/8M

947

118

E3/34M

233

29

E4/140M

57.4

7.2

• When time-slots turn into parallel form (8 bits in parallel) memory

speed requirement decreased by a factor of 8

• Present day memory technology enables up to 256 PDH E1 signals

to be written to and read from a SRAM memory on wire speed

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

8 - 35

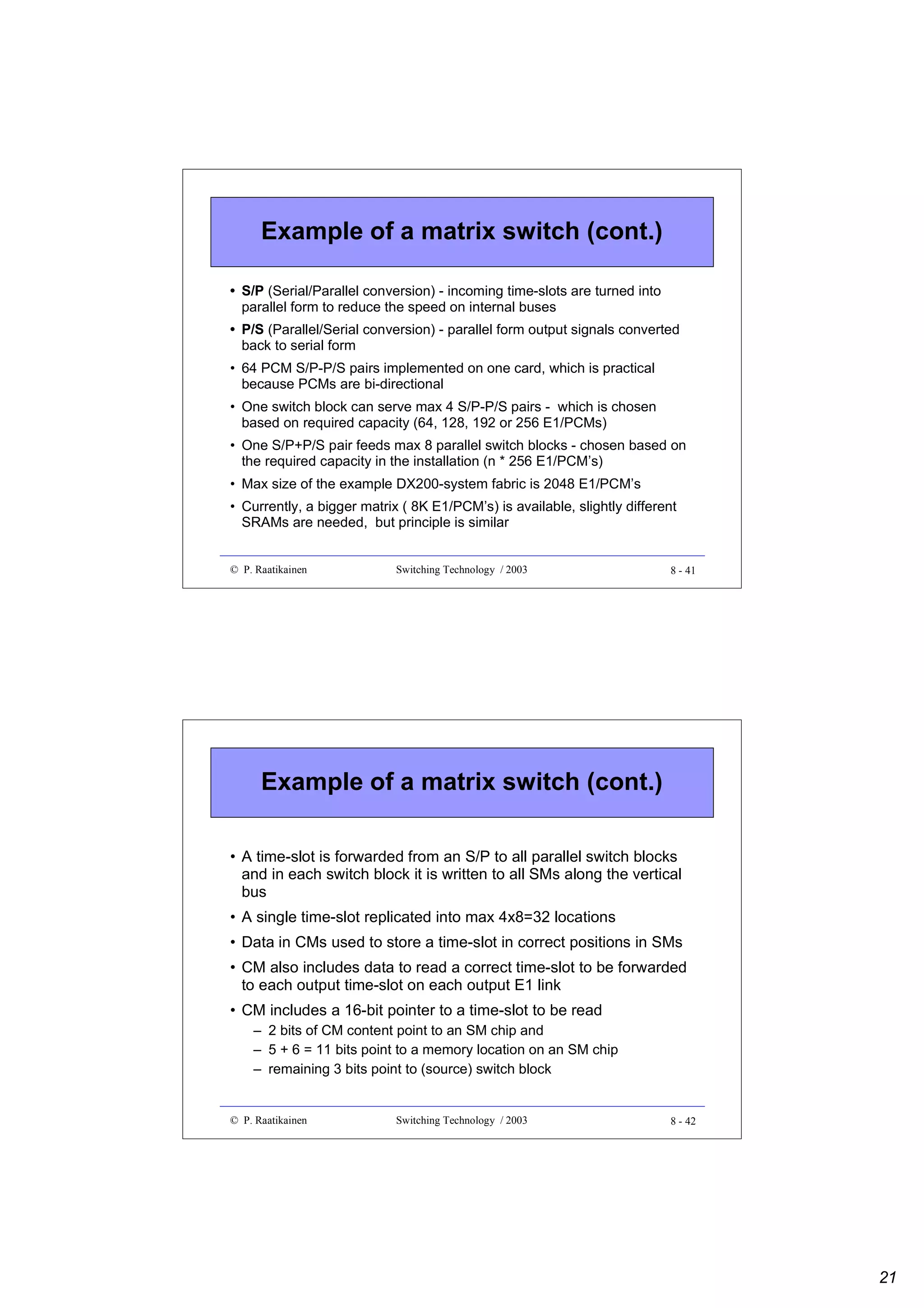

Properties of full matrix switches

Pros

• strict-sense non-blocking

• no path search - a connection can always be written into the

control memory if requested output is idle

• multi-cast capability

• constant delay

• multi-slot connections possible

Cons

• switch and control memory both increase in square of the number

of input/outputs

• broadband - required memory speed may not be available

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

8 - 36

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-201-2048.jpg)

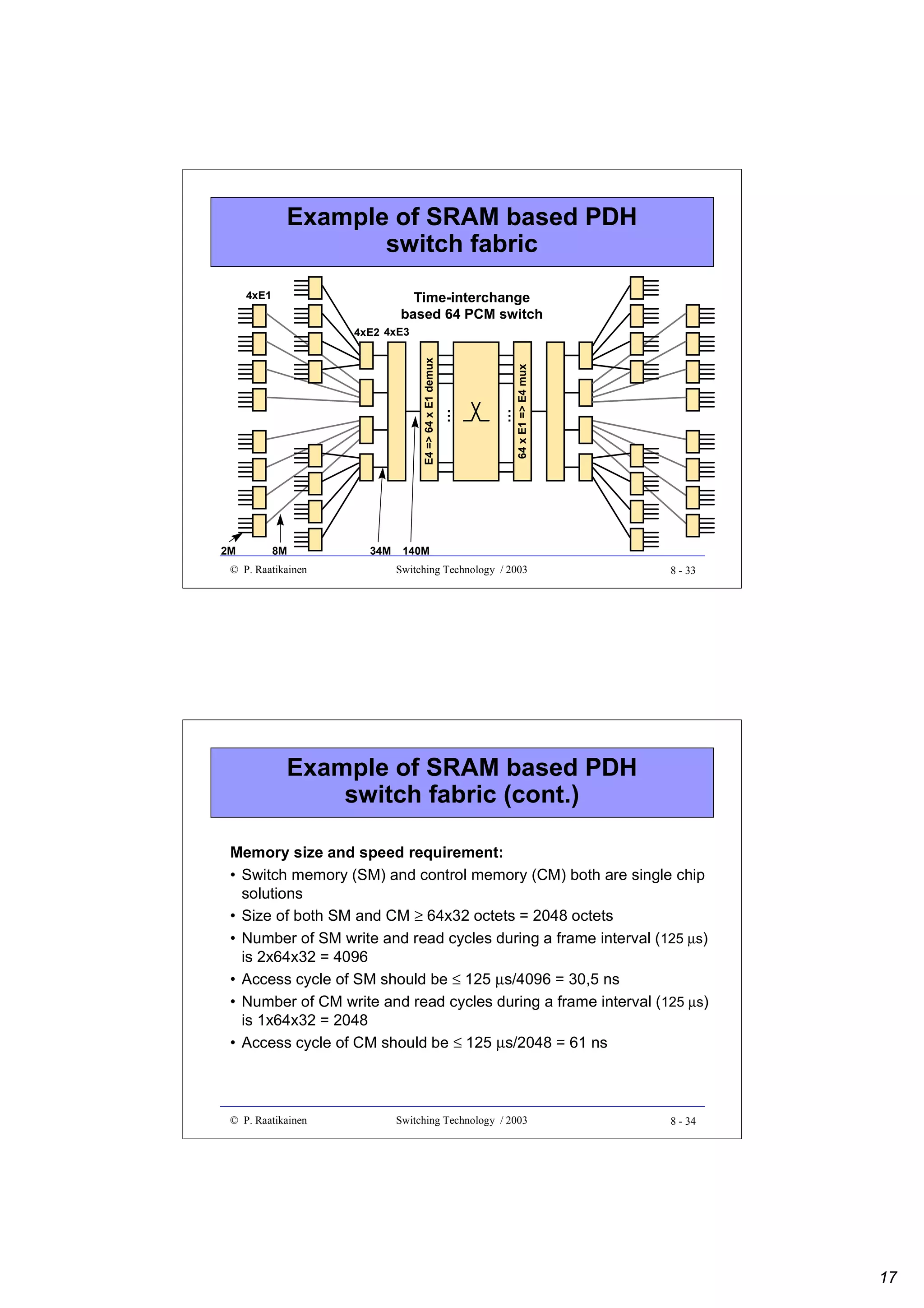

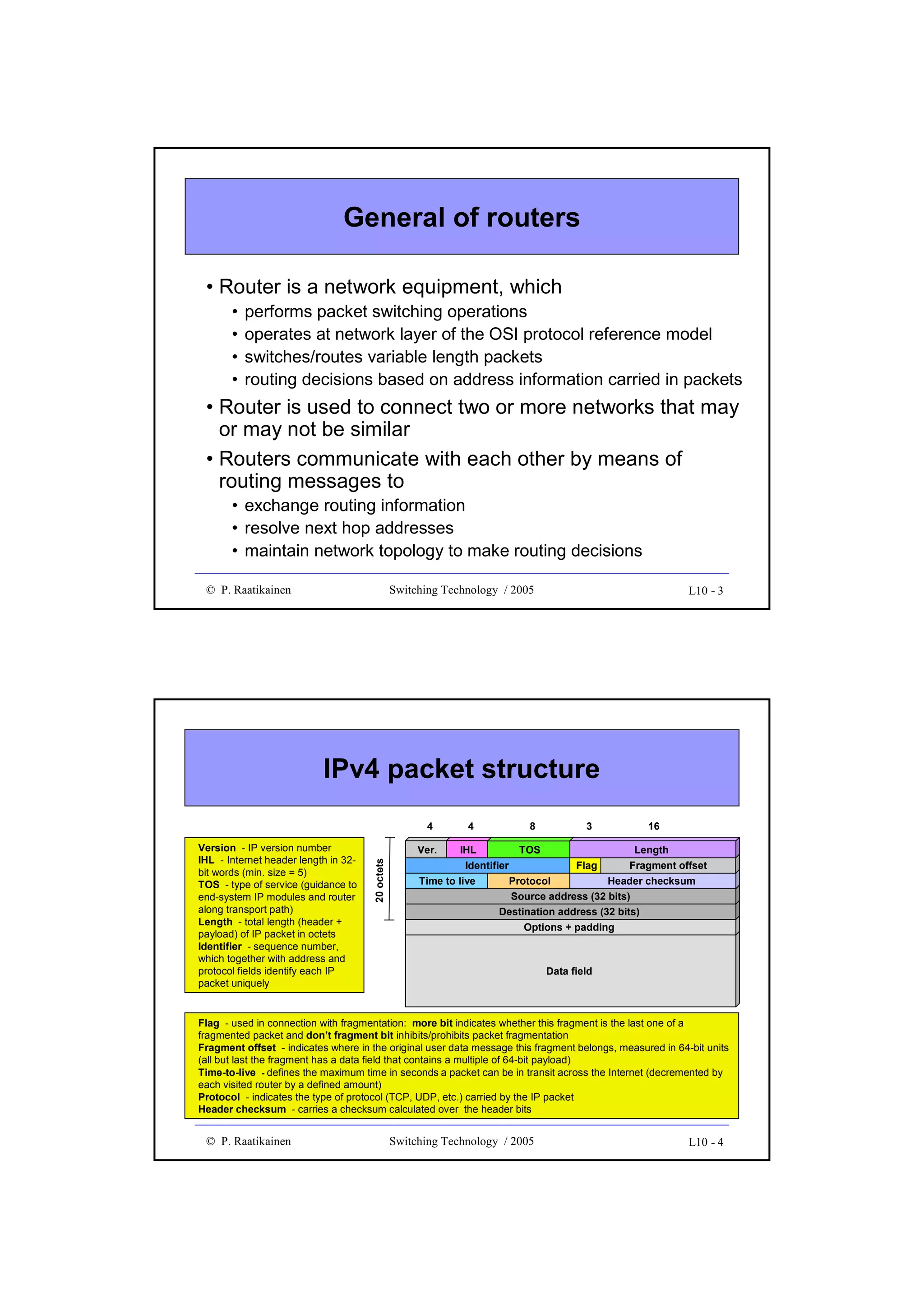

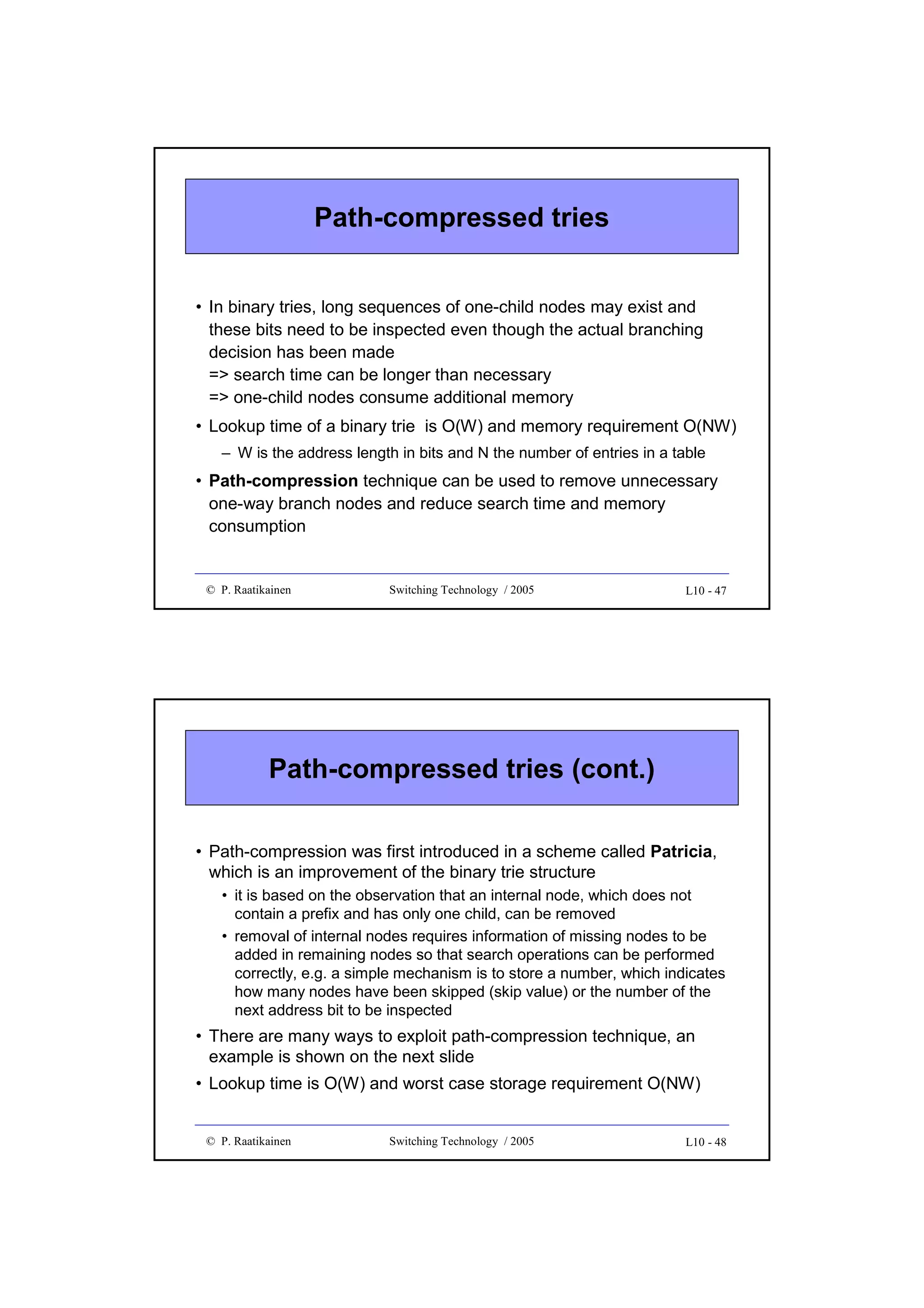

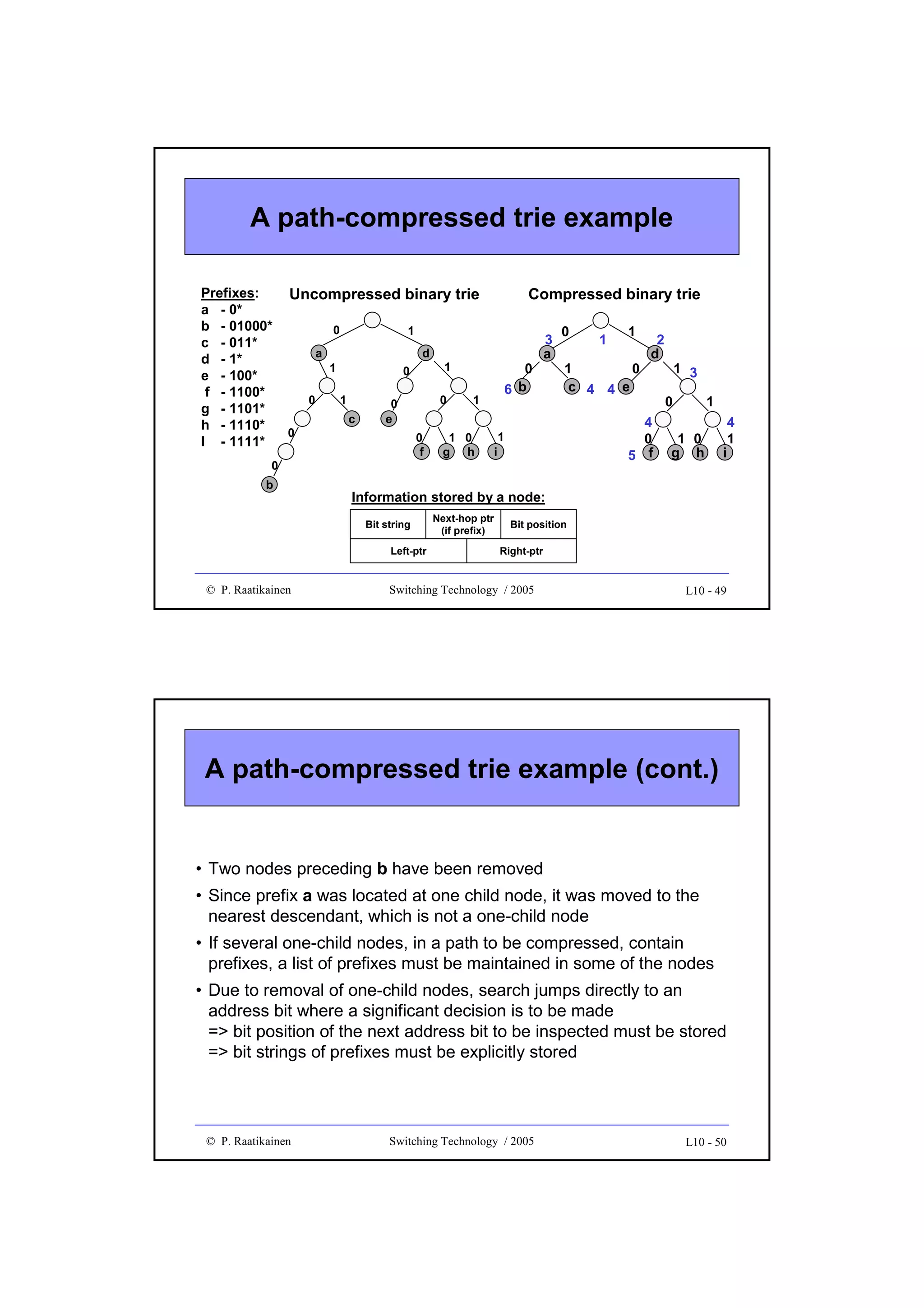

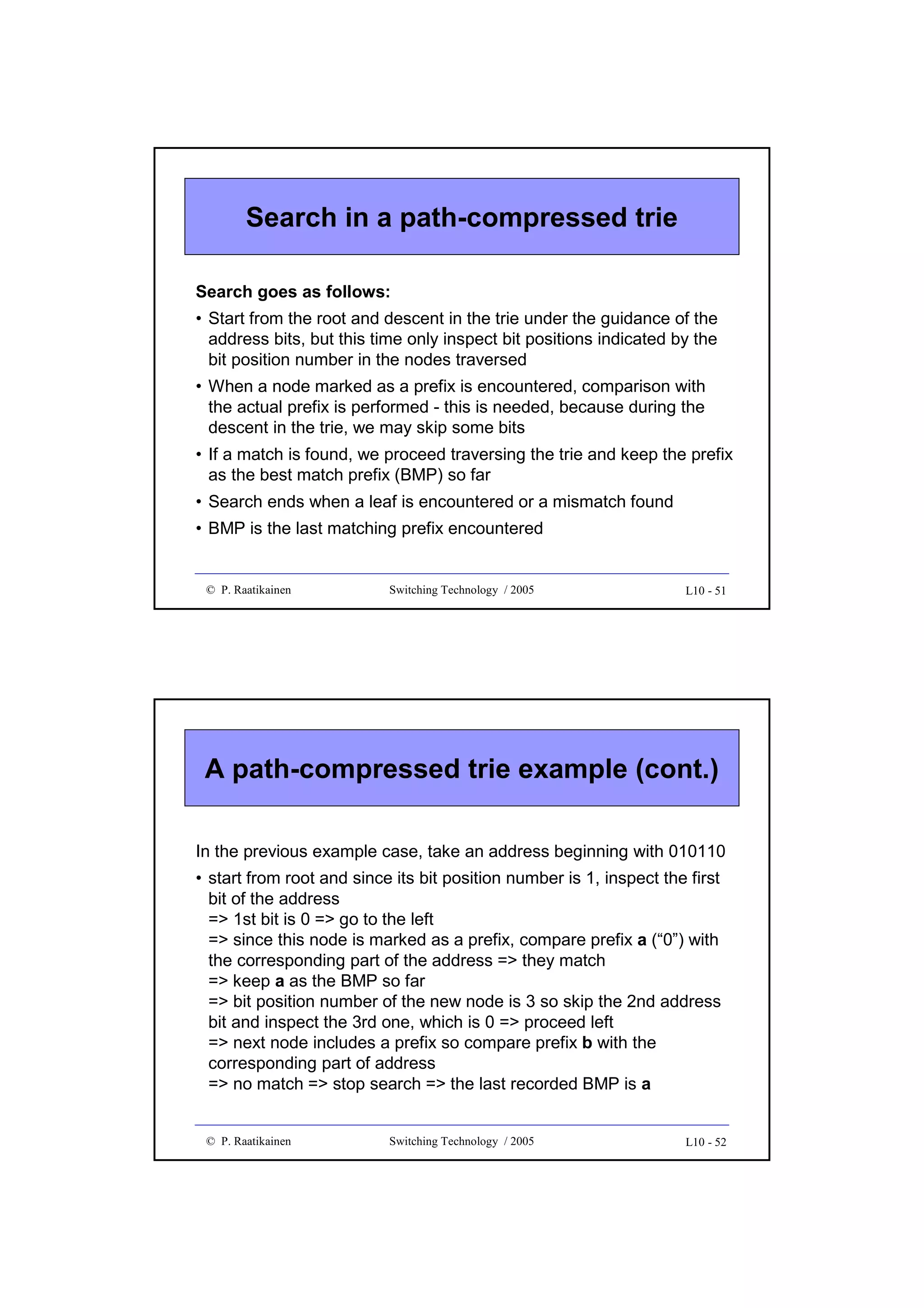

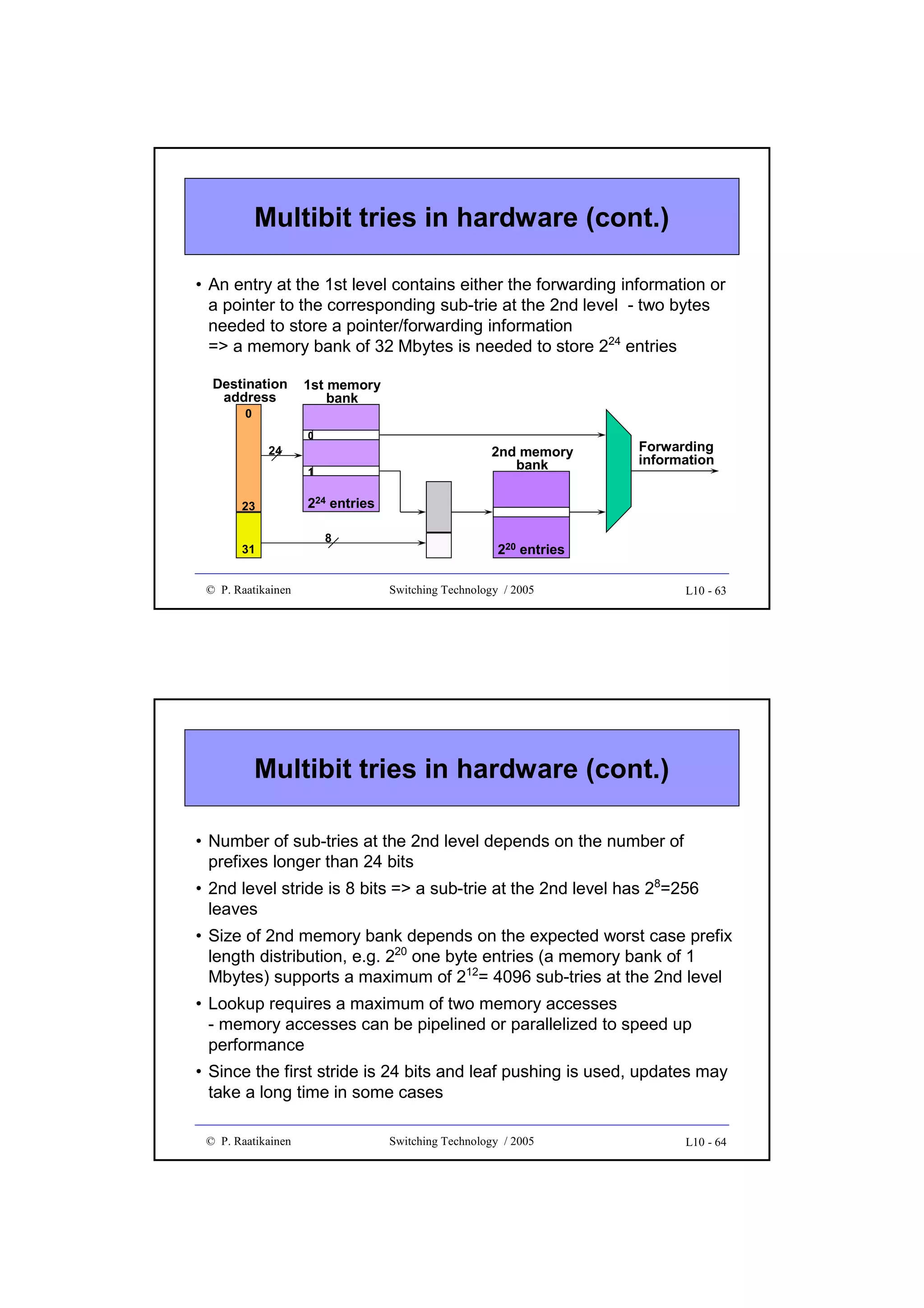

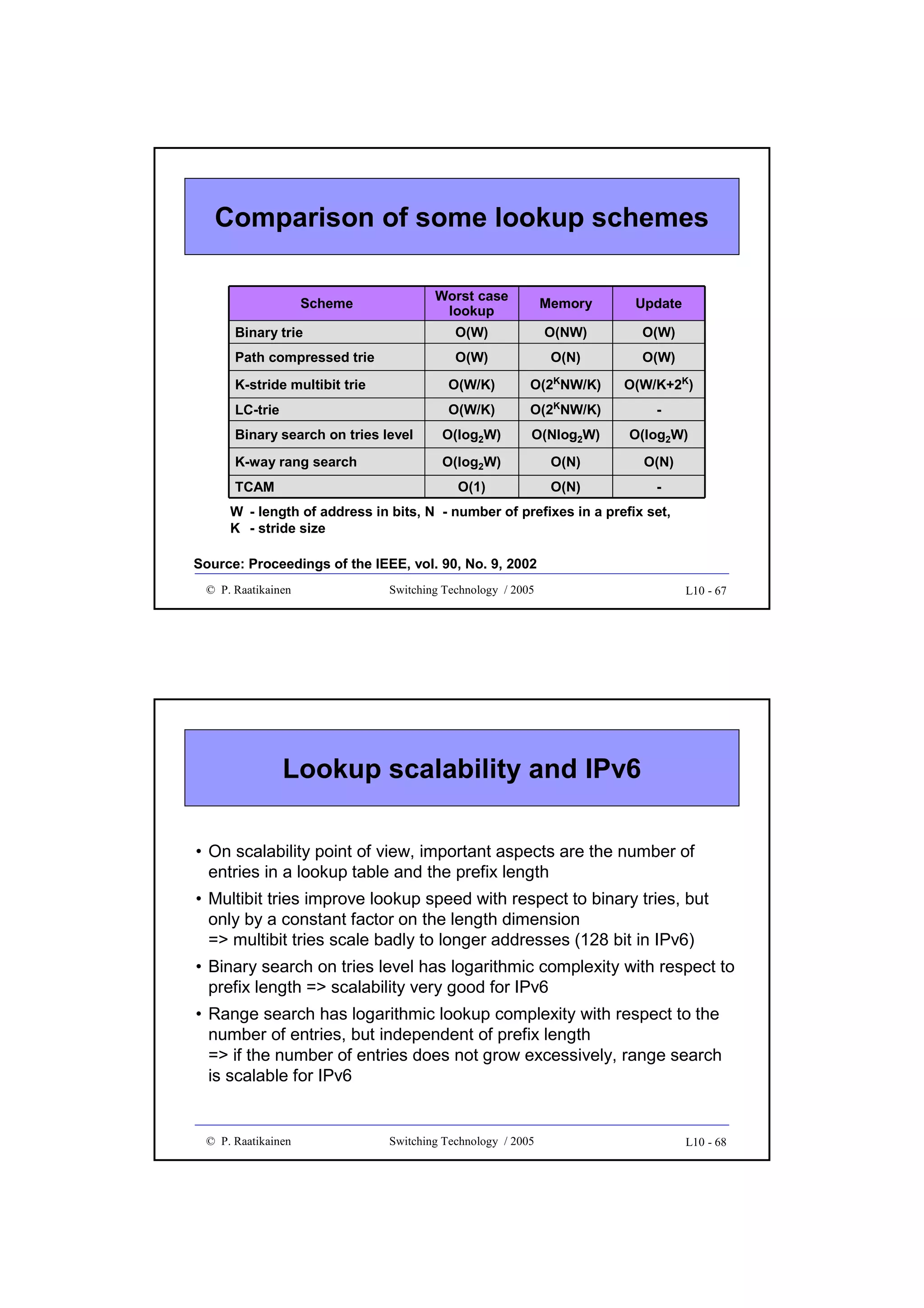

![New directions in IP lookup

• More efficient lookup schemes have been developed to improve the

average lookup performance and storage complexity

• Examples of new methods are

• Binary search on trie levels, which decomposes the longest prefix

operation into W exact matching operations, each performed on prefixes

of equal length

• Multiway or K-way range search, which applies a binary search to best

matching prefixes by using two routing entries per prefix and with some

precomputation

• Ternary CAM uses a special CAM (Content Addressable Memory),

which performs parallel comparisons internally. TCAM stores each W-bit

field as a [val, mask] pair and when a bit string is presented to the input,

TCAM outputs the location (or address) where a match is found.

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2005

L10 - 65

New directions in IP lookup (cont.)

• Conventional routers offer the best-effort service by processing each

incoming packet in the same way. New applications require different

QoS levels and to meet these requirements new mechanisms, such

as admission control, resource reservation and per-flow queuing,

need to be implemented in routers.

• Routers are required to distinguish and classify incoming traffic into

different flows

• Flows are specified by rules and each rule consists of operations for

comparing packet fields with certain values

• Packet fields to be inspected are collected from different protocols

=> packet classification

© P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2005

L10 - 66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-272-2048.jpg)

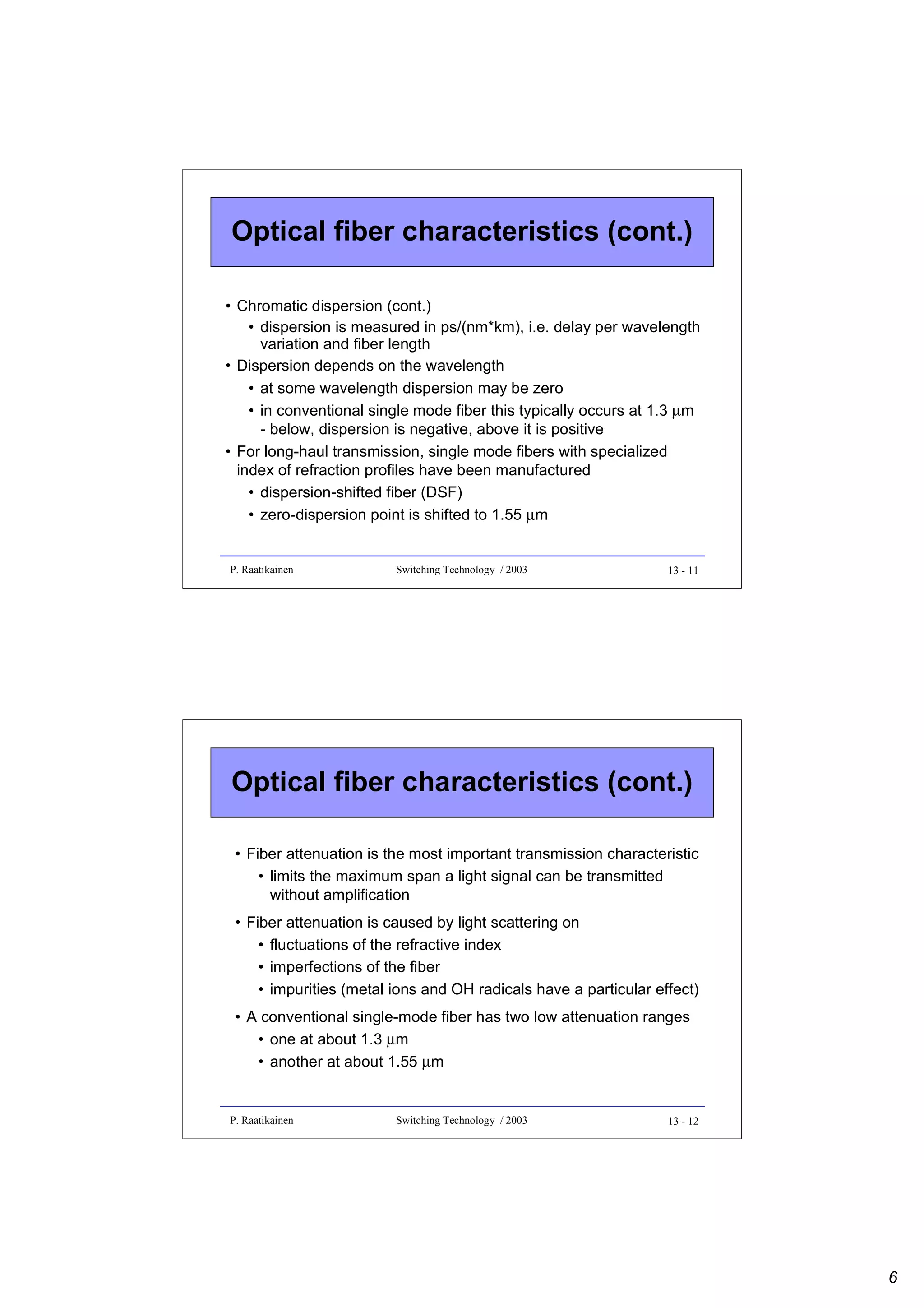

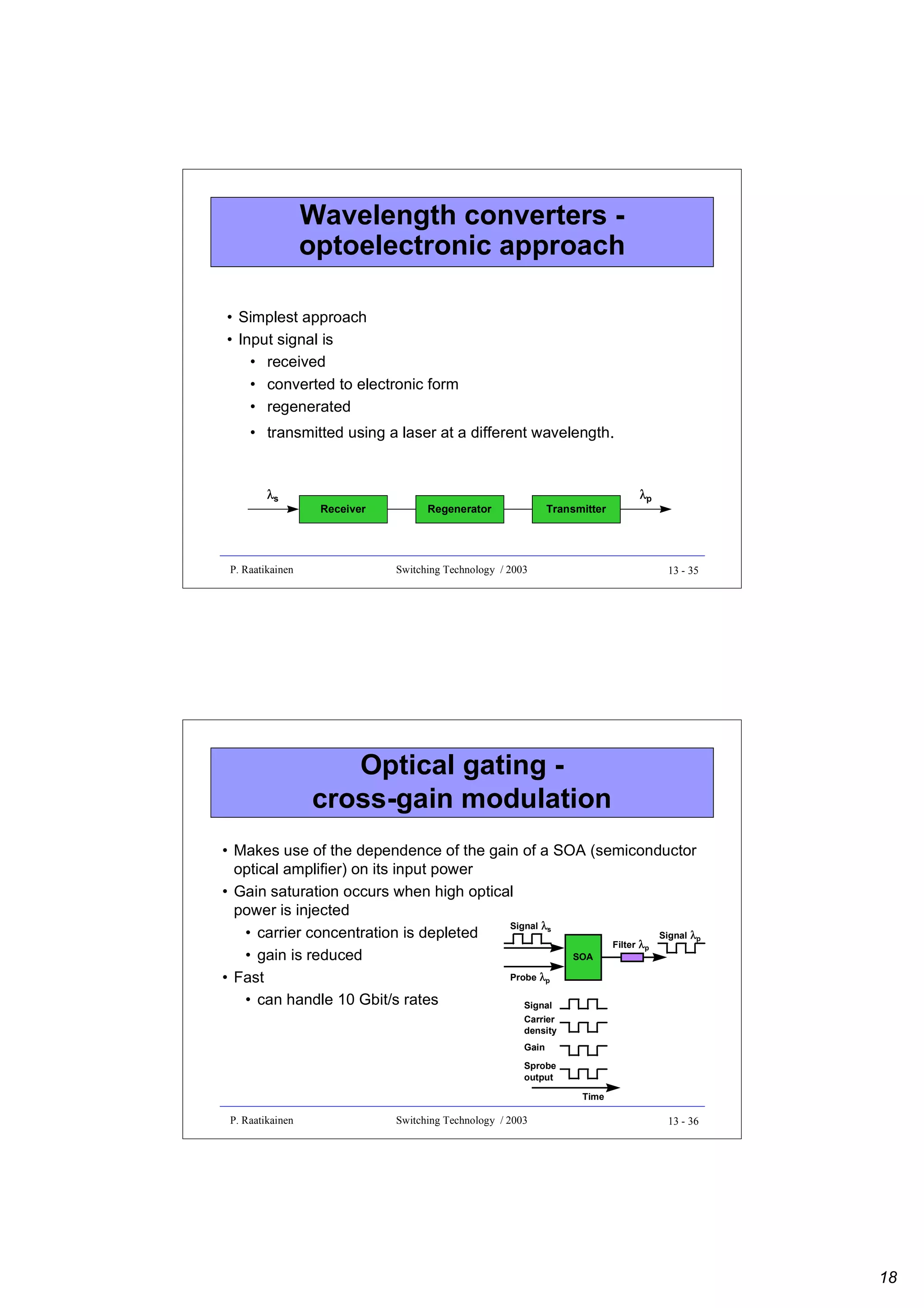

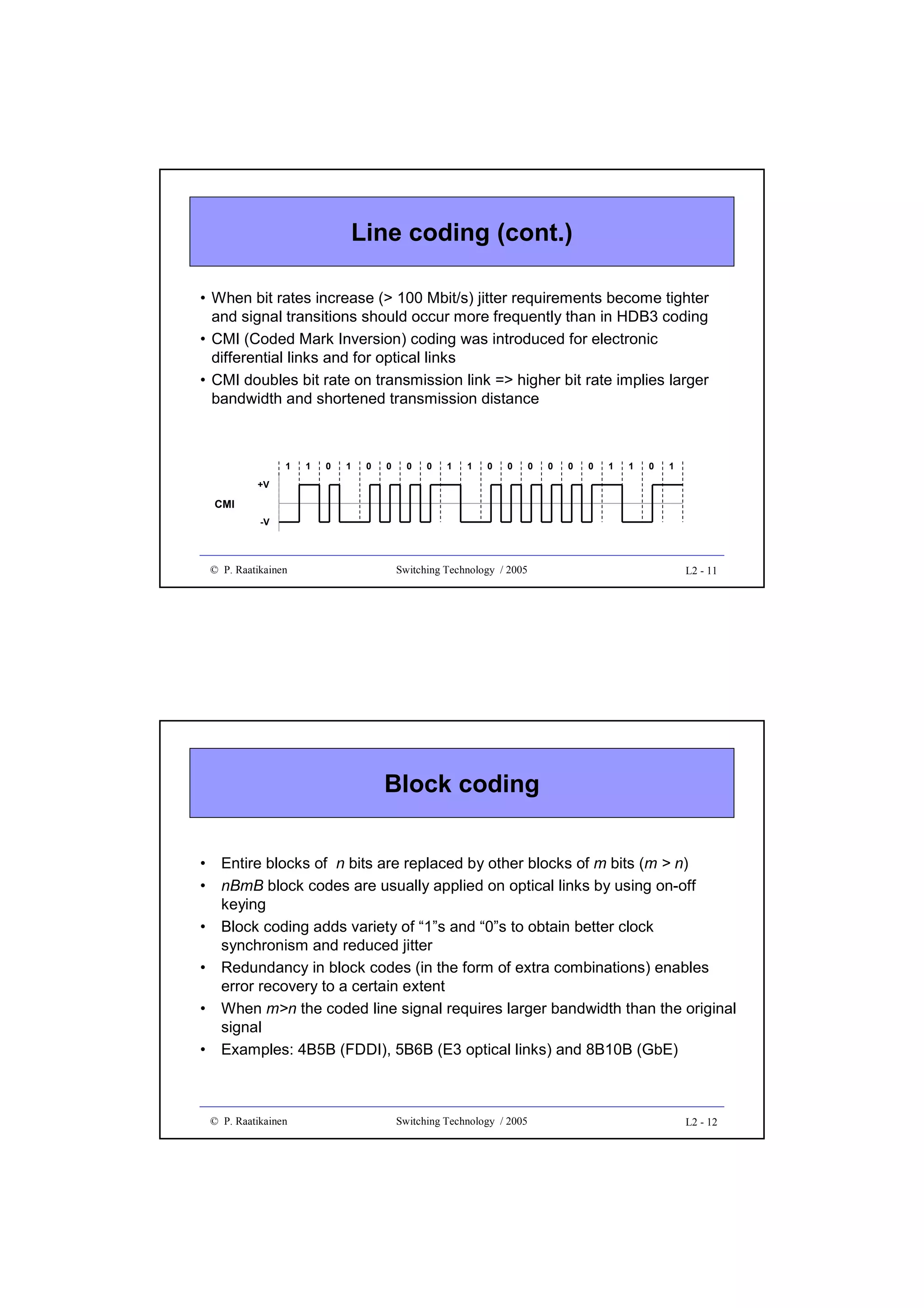

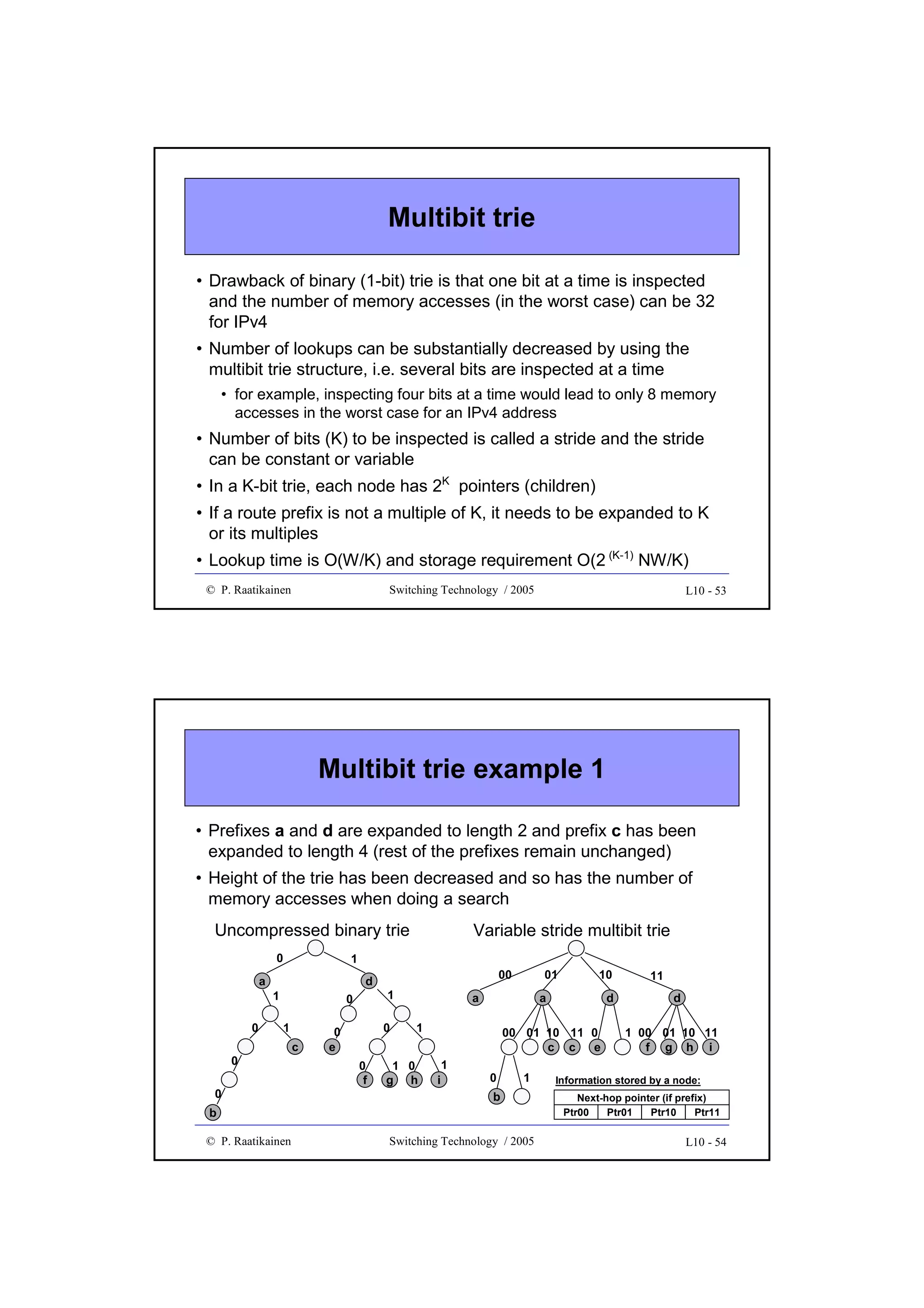

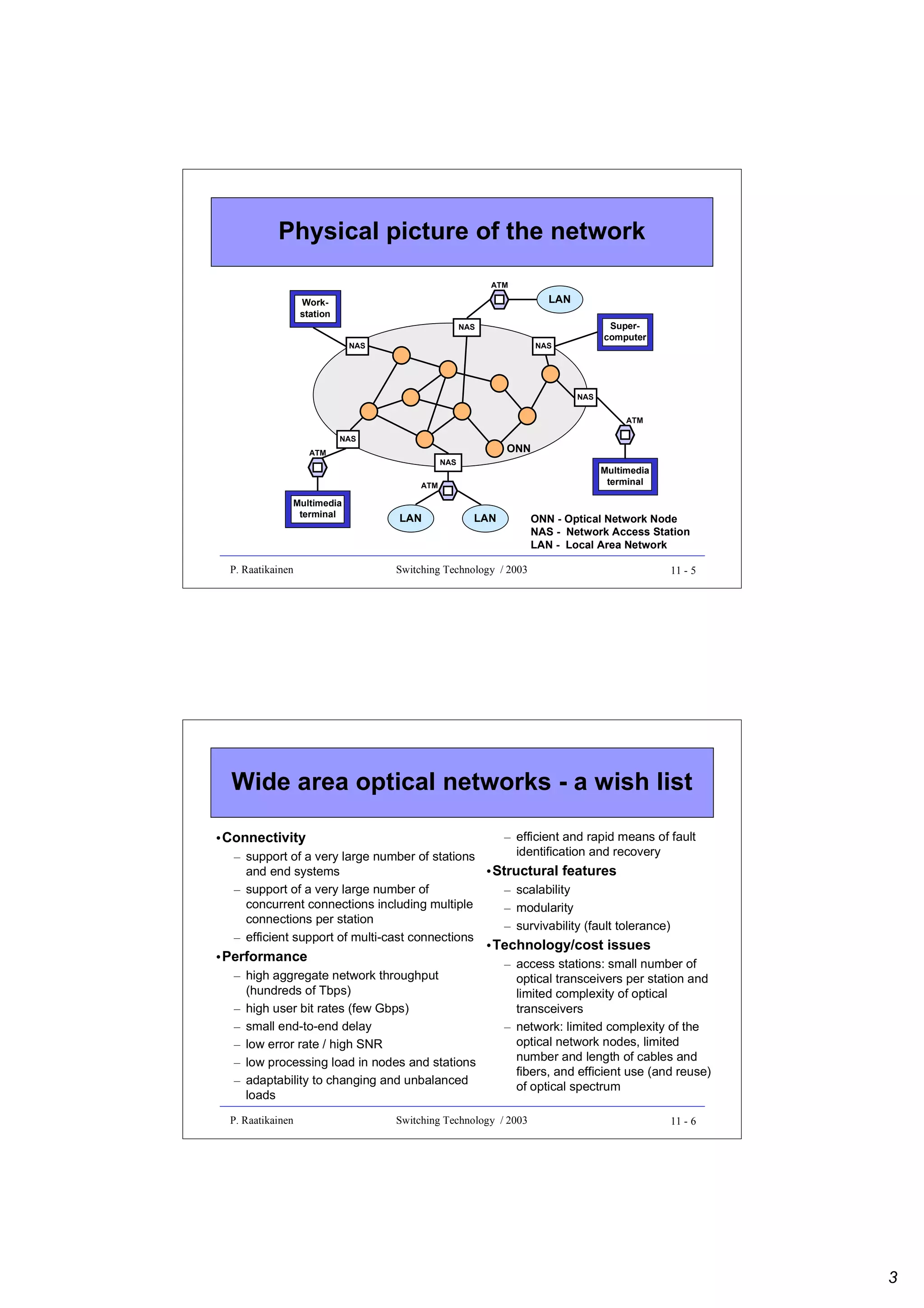

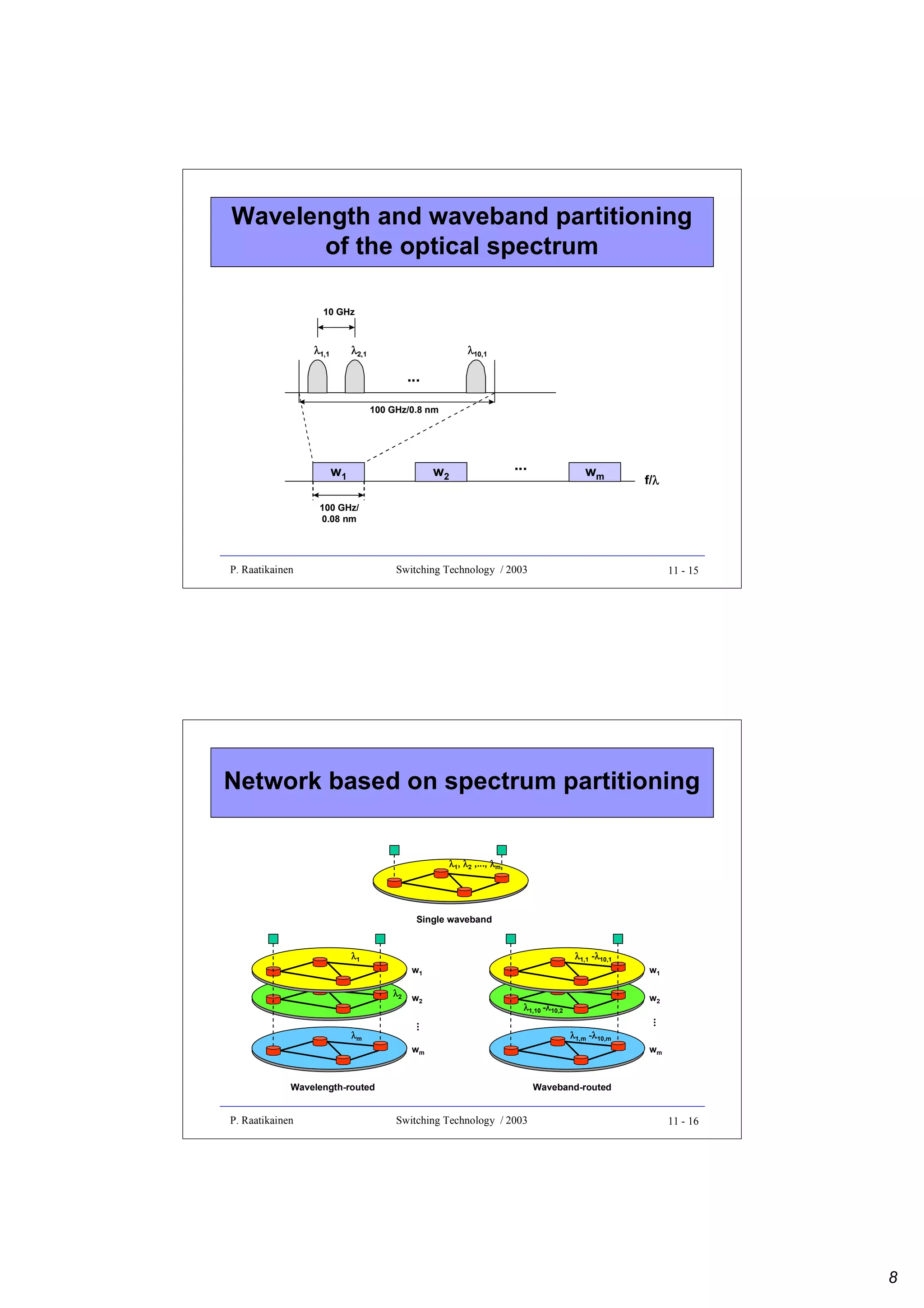

![Optical spectrum

• Since wavelength λ and frequency f are related by f λ = c, where c is the

velocity of light in the medium, we have the relation

∆ f ≈ − c ∆λ

2

λ

• Thus, 10 GHz ≈ 0.08 nm and 100 GHz ≈ 0.8 nm in the range of 1,550 nm,

where most modern lightwave networks operate

• The 10-GHz channel spacing is sufficient to accommodate λ-channels

carrying aggregate digital bit rates on the order of 1 Gbps

- modulation efficiency of 0.1 bps/Hz typical for optical systems

• The 10-GHz channel spacing is suitable for optical receivers, but much too

dense to permit independent wavelength routing at the network nodes

- for this, 100-GHz channel spacing is needed.

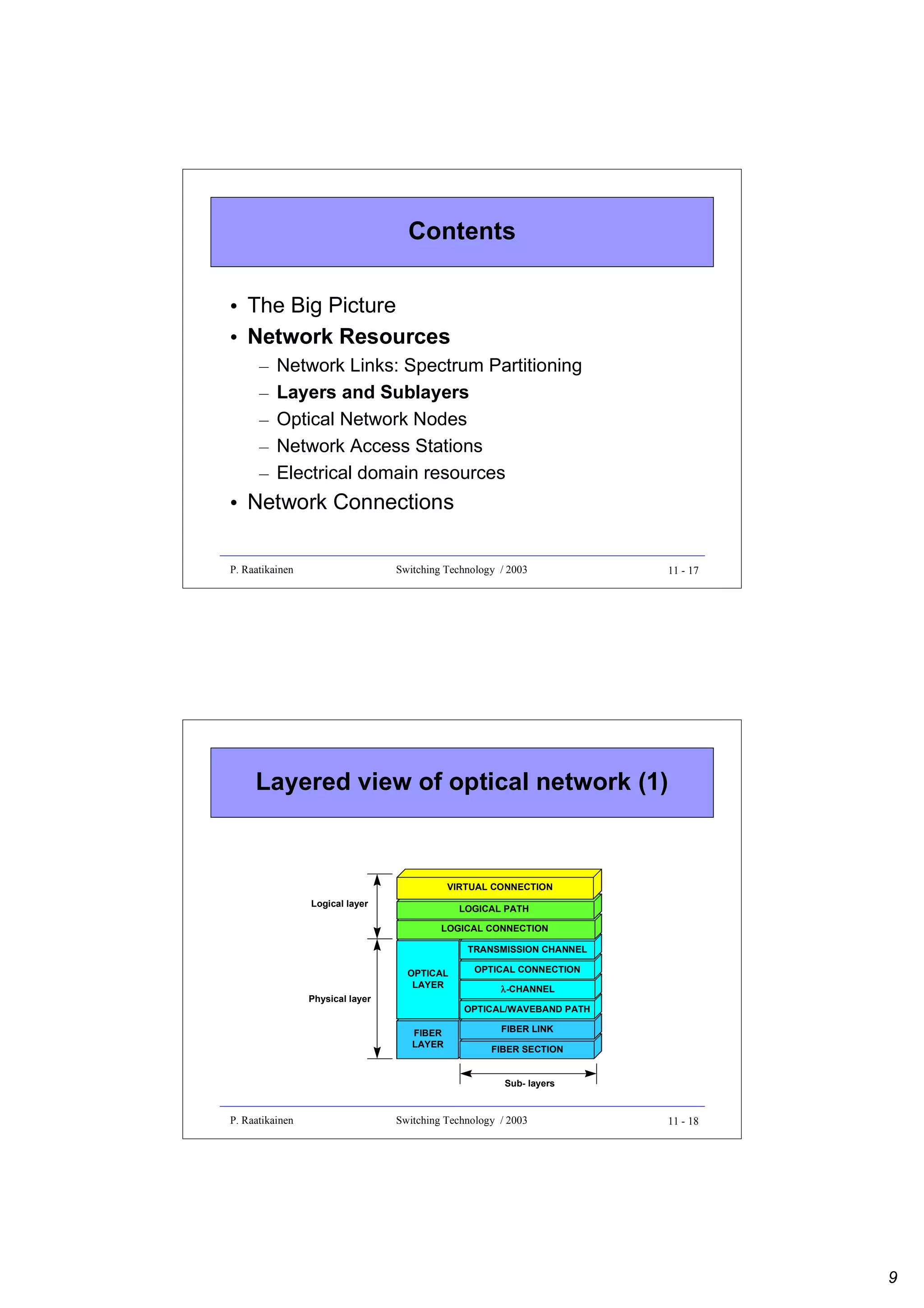

• In a waveband routing network, several λ-channels (with 10-GHz channel

spacing) comprise an independently routed waveband (with 100-GHz

spacing between wavebands).

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 13

Wavelength partitioning of the optical

spectrum

Unusable spectrum

λ1

λ2

λm

...

λ

f/λ [GHz/nm]

10 GHz

0.08 nm

λ-channel spacing for separability at receivers

λ1

λ2

λm

...

f/λ

λ

100 GHz/0.8 nm

λ-channel spacing for separability at network nodes

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 14

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-280-2048.jpg)

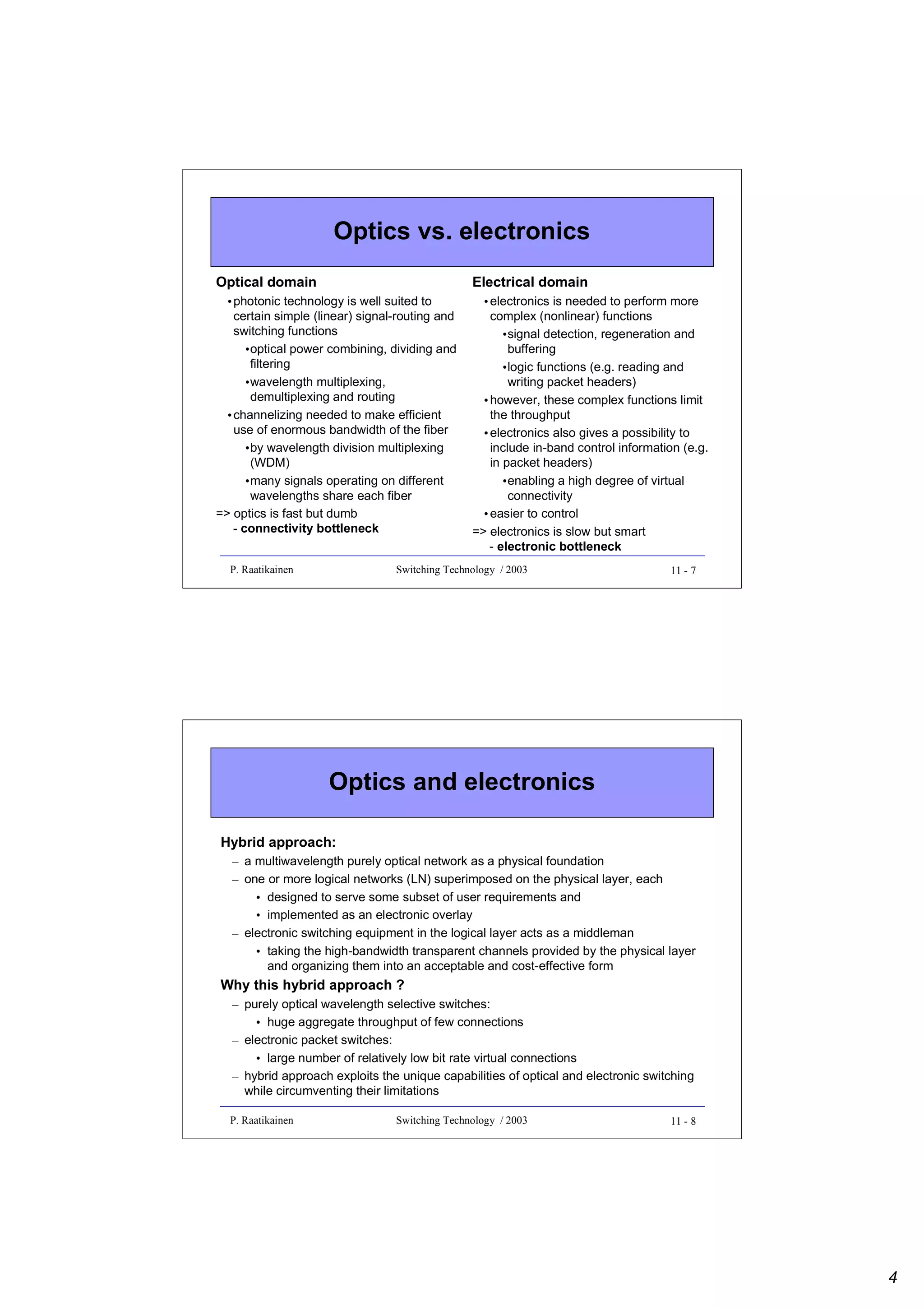

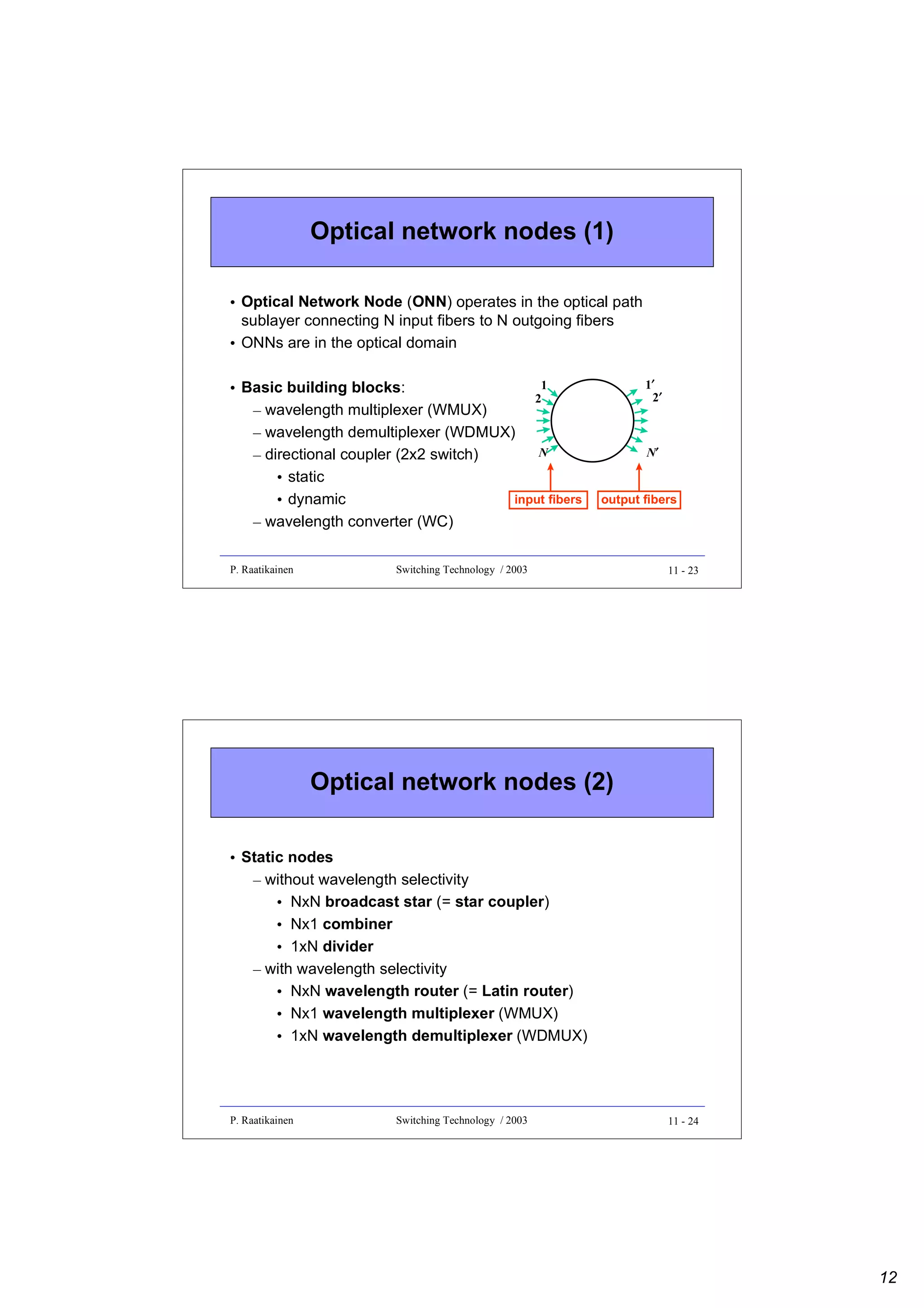

![Directional Coupler (1)

• Directional coupler (= 2x2 switch) is an optical four-port

– ports 1 and 2 designated as input ports

– ports 1’ and 2’ designated as output ports

• Optical power

– enters a coupler through fibers attached to input ports,

– divided and combined linearly

– leaves via fibers attached to output ports

• Power relations for input signal powers

powers P1′ and P2′ are given by

P1 and P2 and output

P ′ = a11 P + a12 P2

1

1

P2′ = a21 P + a22 P2

1

1

• Denote the power transfer matrix by A

P. Raatikainen

= [aij]

2

a11

a21

a12

1′

2′

a22

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 27

Directional Coupler (2)

• Ideally, the power transfer matrix A is of the form

1 − α

A=

α

α

,

1−α

0 ≤α ≤1

• If parameter α is fixed, the device is static, e.g. with α = 1/2 and

signals present at both inputs, the device acts as a 2x2 star coupler

• If α can be varied through some external control, the device is

dynamic or controllable, e.g. add-drop switch

• If only input port 1 is used (i.e., P2 = 0),

1

the device acts as a 1x2 divider

• If only output port 1’ is used (and port 2’ is

2

terminated), the device acts as a 2x1 combiner

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

1−α

α

α

1−α

1′

2′

11 - 28

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-287-2048.jpg)

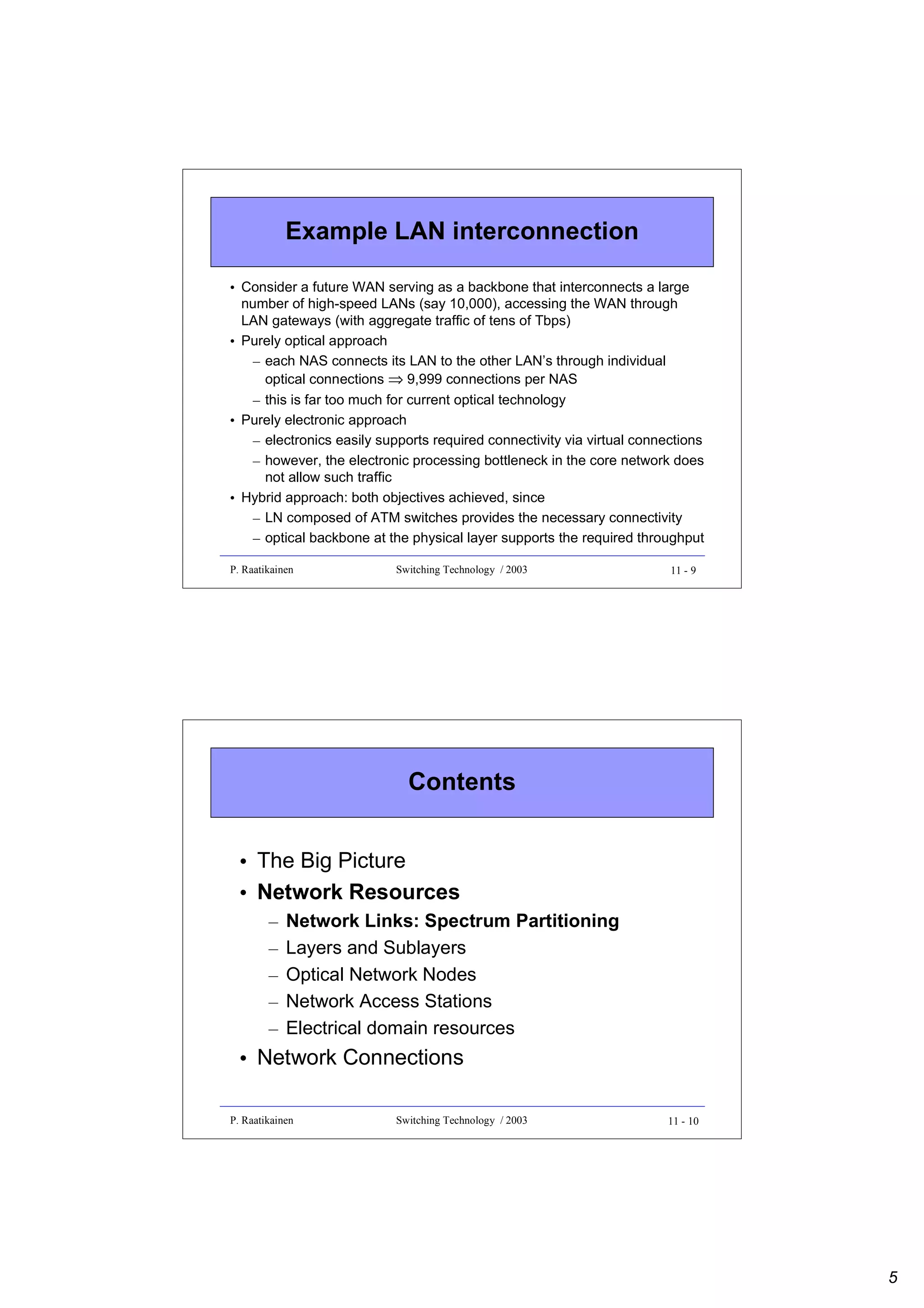

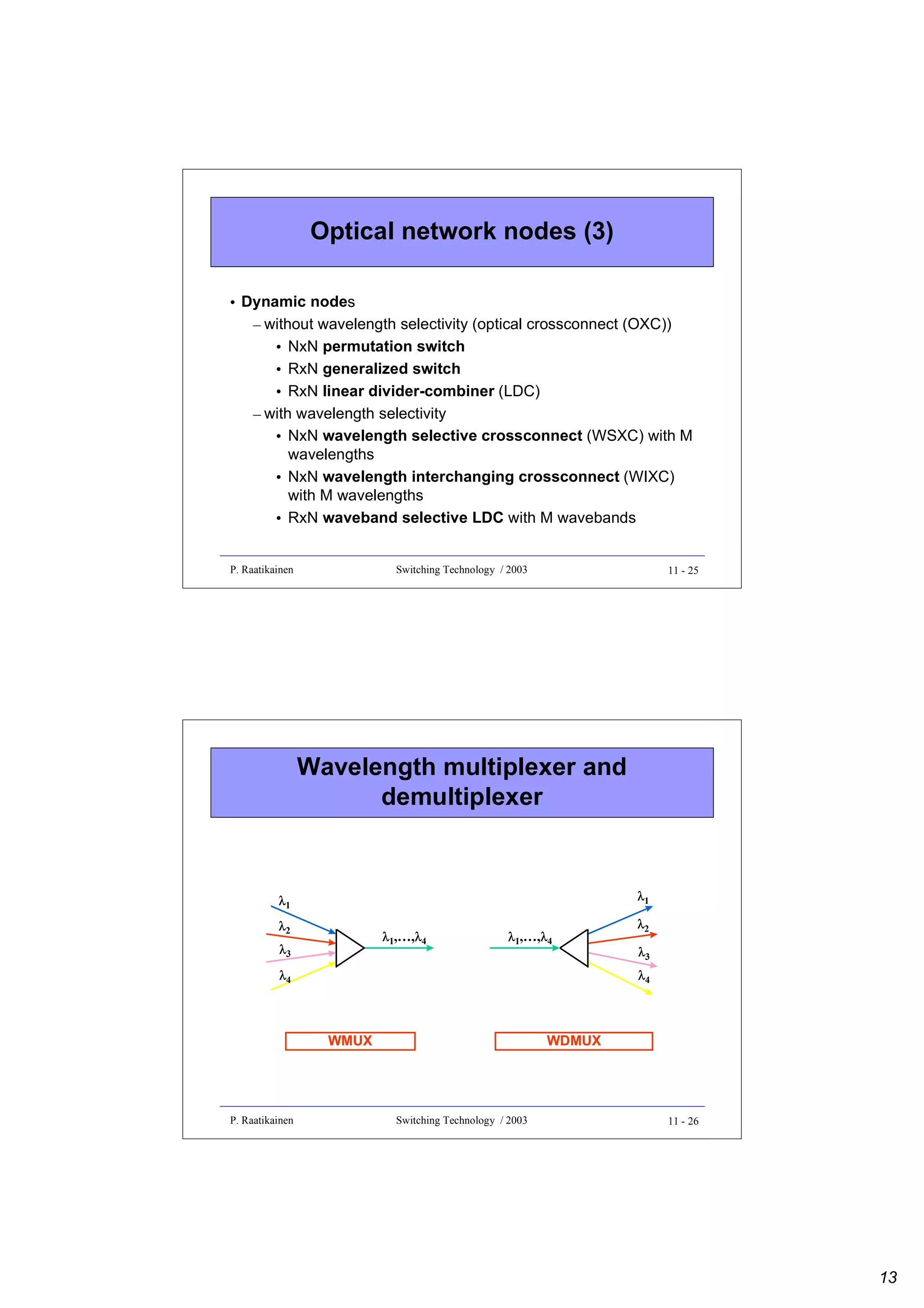

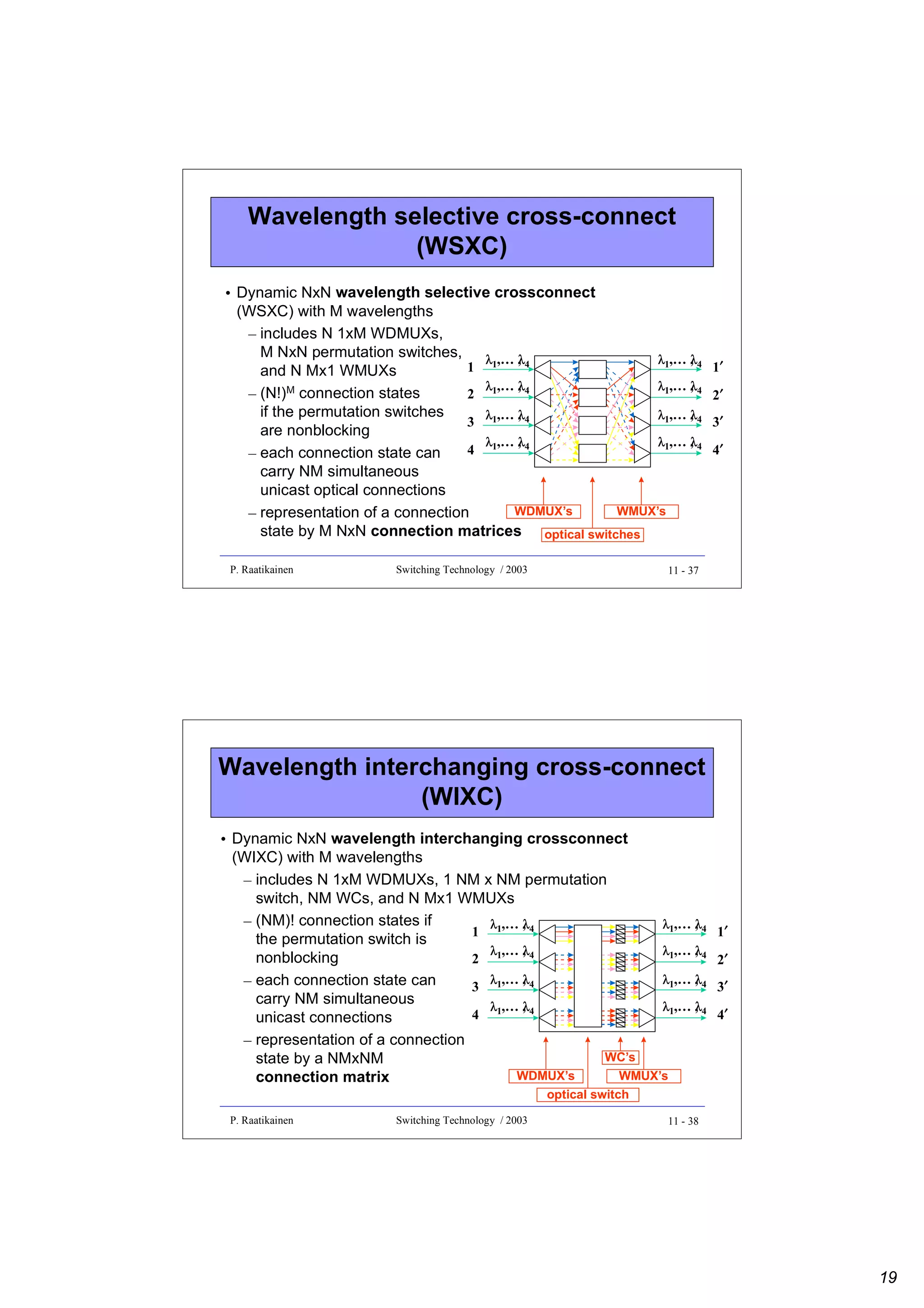

![Permutation switch

P. Raatikainen

1′

2′

3′

4′

output ports

1′ 2′ 3′ 4′

input ports

1

• Dynamic NxN permutation switch

(e.g. crossbar switch)

2

– unicast optical connections

3

between input and output ports

4

– N! connection states (if

nonblocking)

– each connection state can carry N

simultaneous unicast optical

connections

– representation of a connection state

by a NxN connection matrix

1

1

2 1

3

1

4

1

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 33

Generalized switch

• Dynamic RxN generalized switch (e.g.

crossbar switch)

1/N

1/N

1/N

1/N

1

– any input/output pattern possible

2

– 2NR connection states

3

– each connection state can carry (at most)

R simultaneous multicast optical

4

connections

– a connection state represented by a RxN

connection matrix

1 ,

aij = NR

0,

P. Raatikainen

if switch (i,j ) is on

otherwise

Switching Technology / 2003

2′

3′

4′

output ports

1′ 2′ 3′ 4′

input ports

• Input/output power relation P’ = AP with

NxR power transfer matrix A = [aij], where

1/R1/R

1/R

1/R

1′

1

1 1

2 1

1

3

1

4 1 1 1

11 - 34

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-290-2048.jpg)

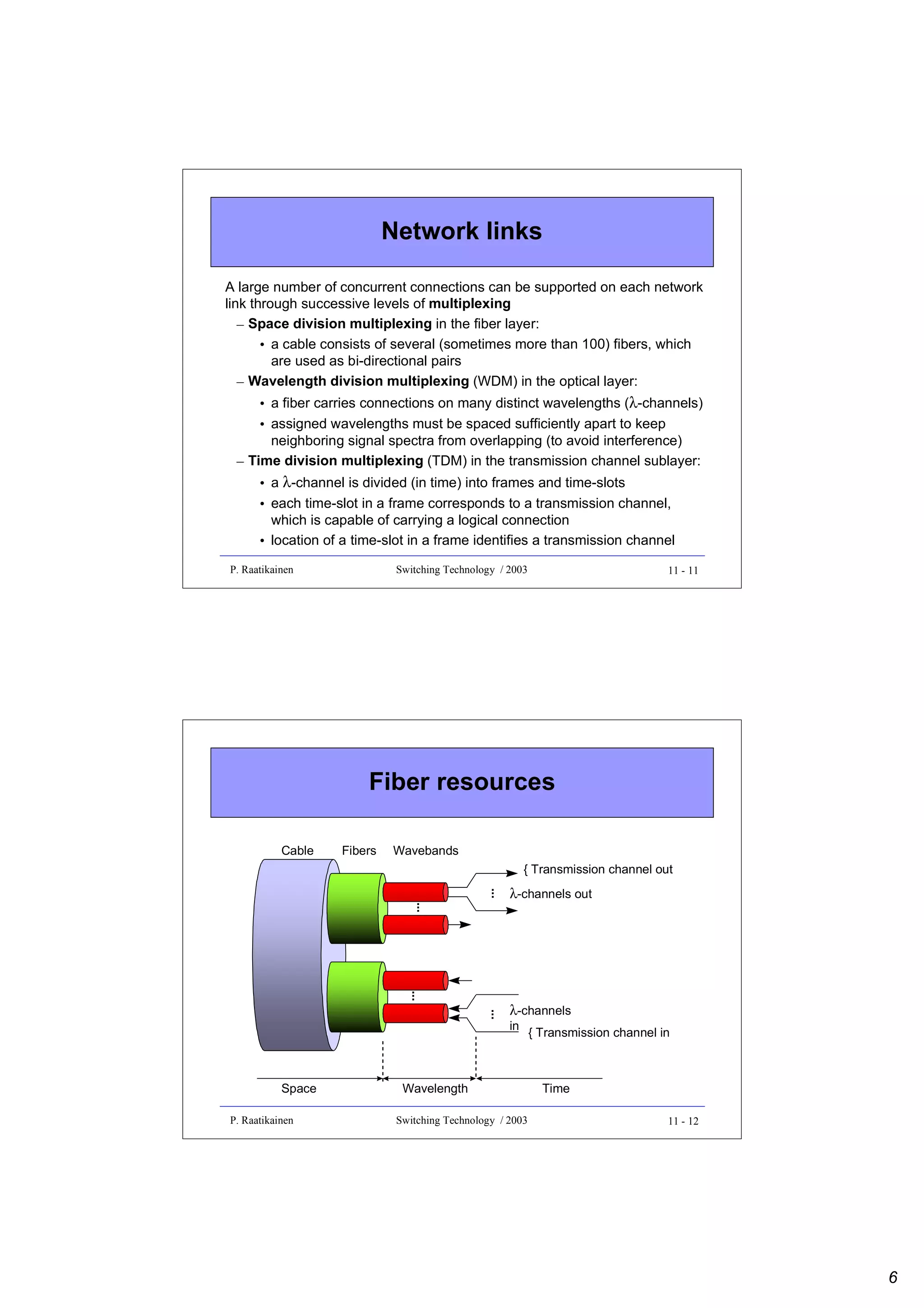

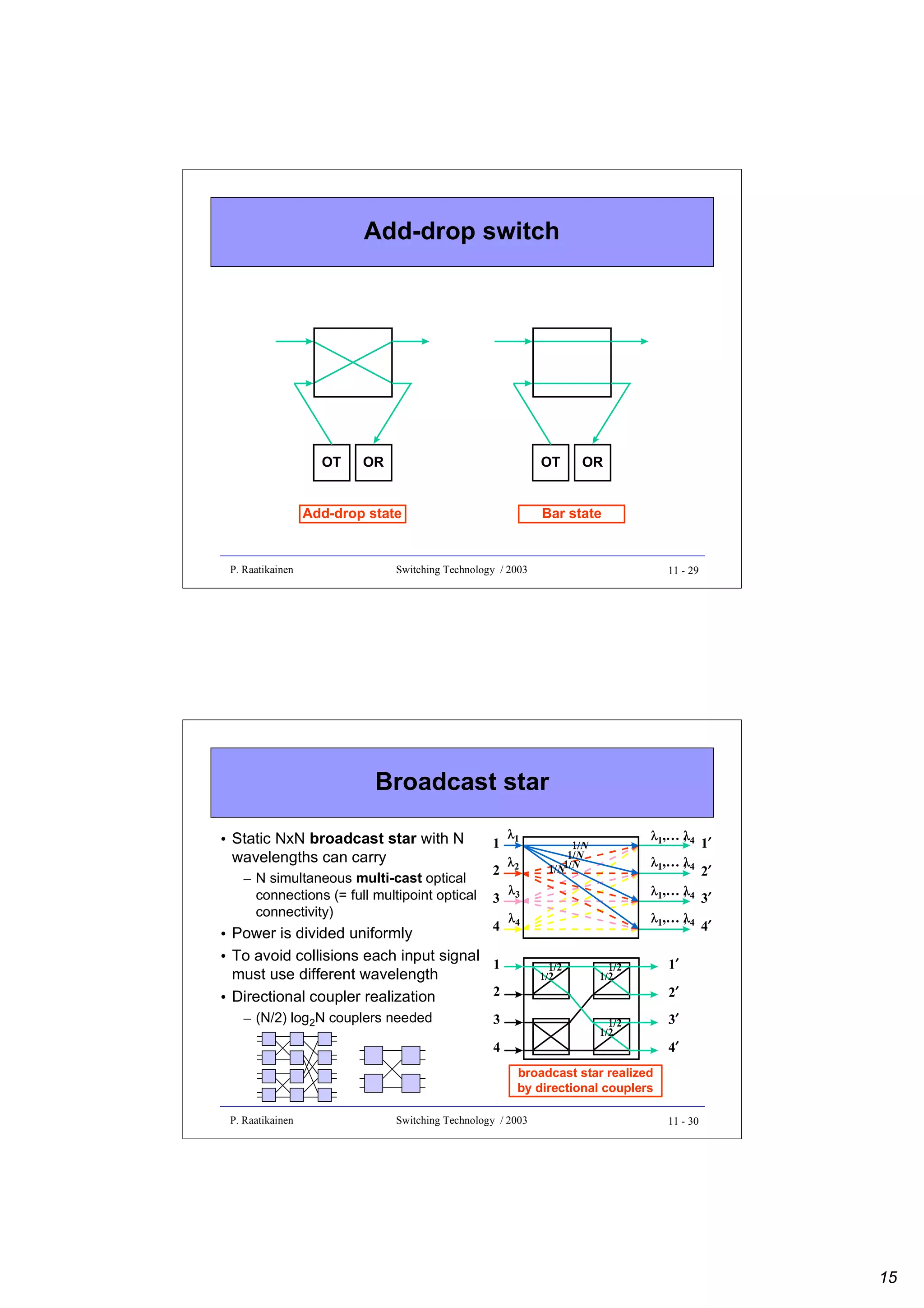

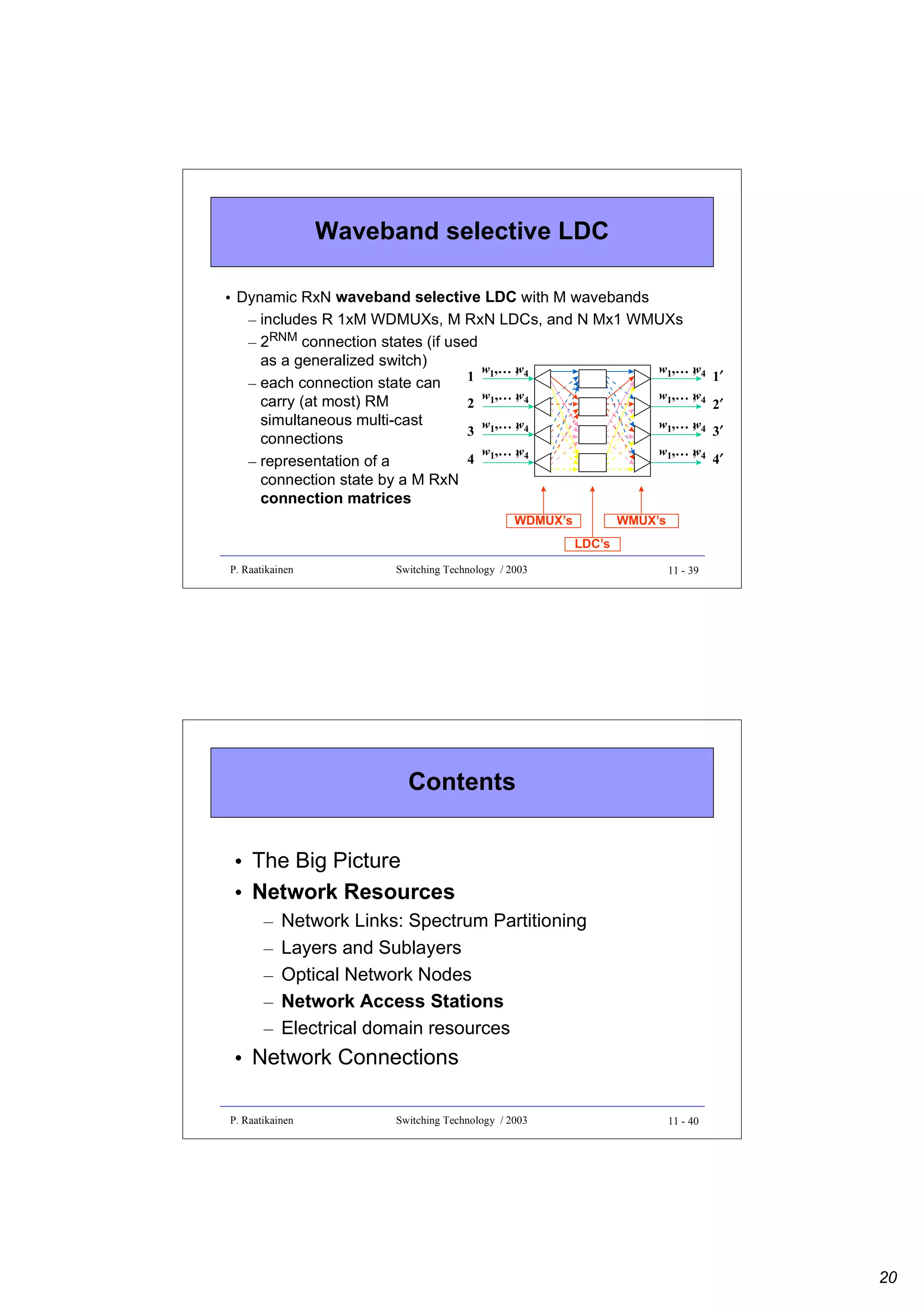

![Linear Divider-Combiner (LDC)

1′

1

δ11

• Linear Divider-Combiner (LDC) is

δ δ21

δ41 31

a generalized switch that

2

– controls power-dividing and

power-combining ratios

3

σ41

– less inherent loss than in crossbar

σ σ42

σ4443

4

• Power-dividing and power-combining ratios

– δij = fraction of power from input port j directed to output port i’

– σij = fraction of power from input port j combined onto output port i

• In an ideal case of lossless couplers, we have constraints

2′

3′

4′

∑ δ ij = 1 and ∑ σ ij = 1

i

j

• The resulting power transfer matrix A = [aij] is such that

aij = δ ijσ ij

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 35

LDC and generalized switch realizations

1

rx1

combiner

directional couplers

11

12

1r

...

22

2r

...

21

2

1xn

splitter

n

...

δ - σ linear divider-combiner

1

2

n1

r

n2

nr

Generalized optical switch

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 36

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-291-2048.jpg)

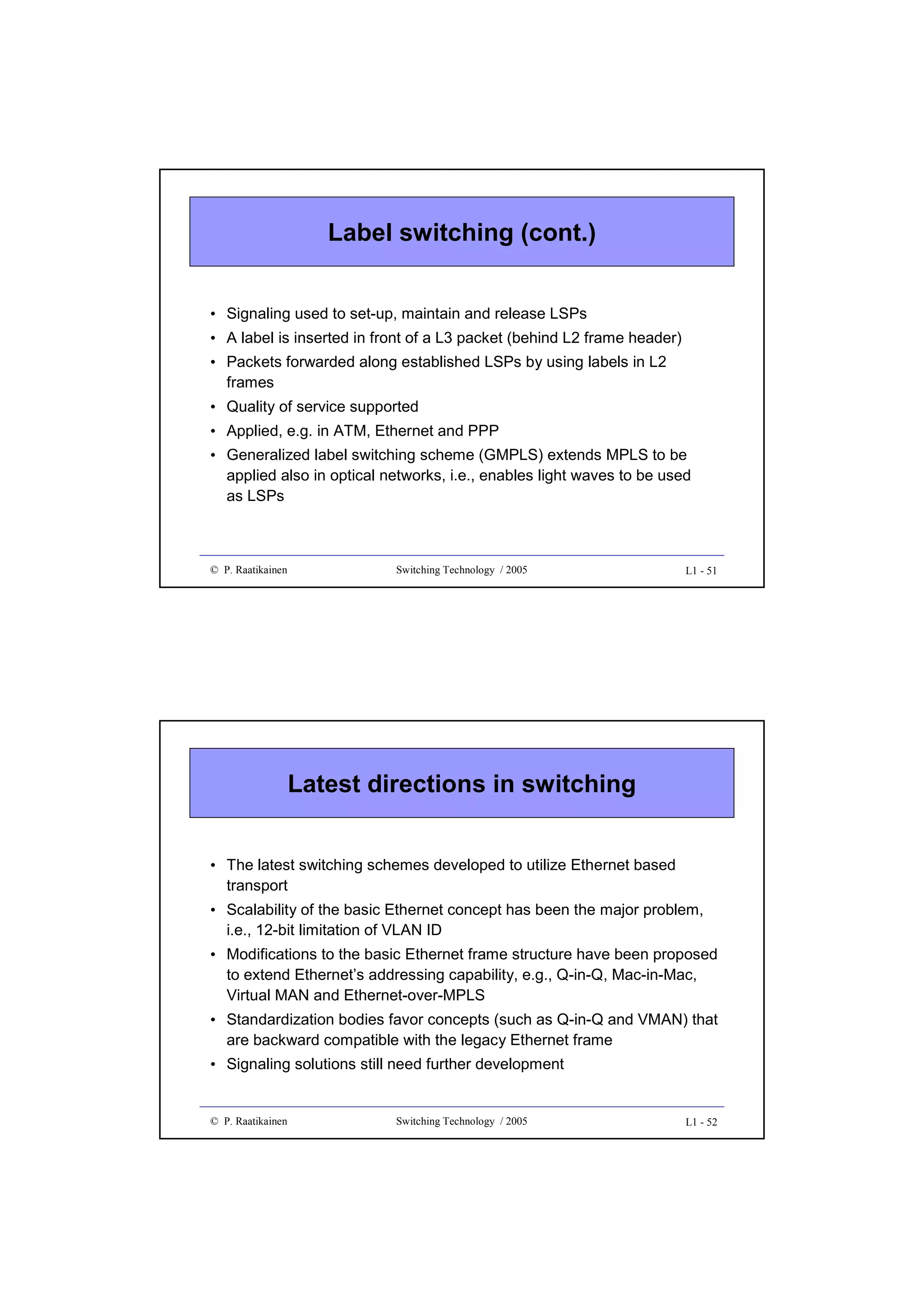

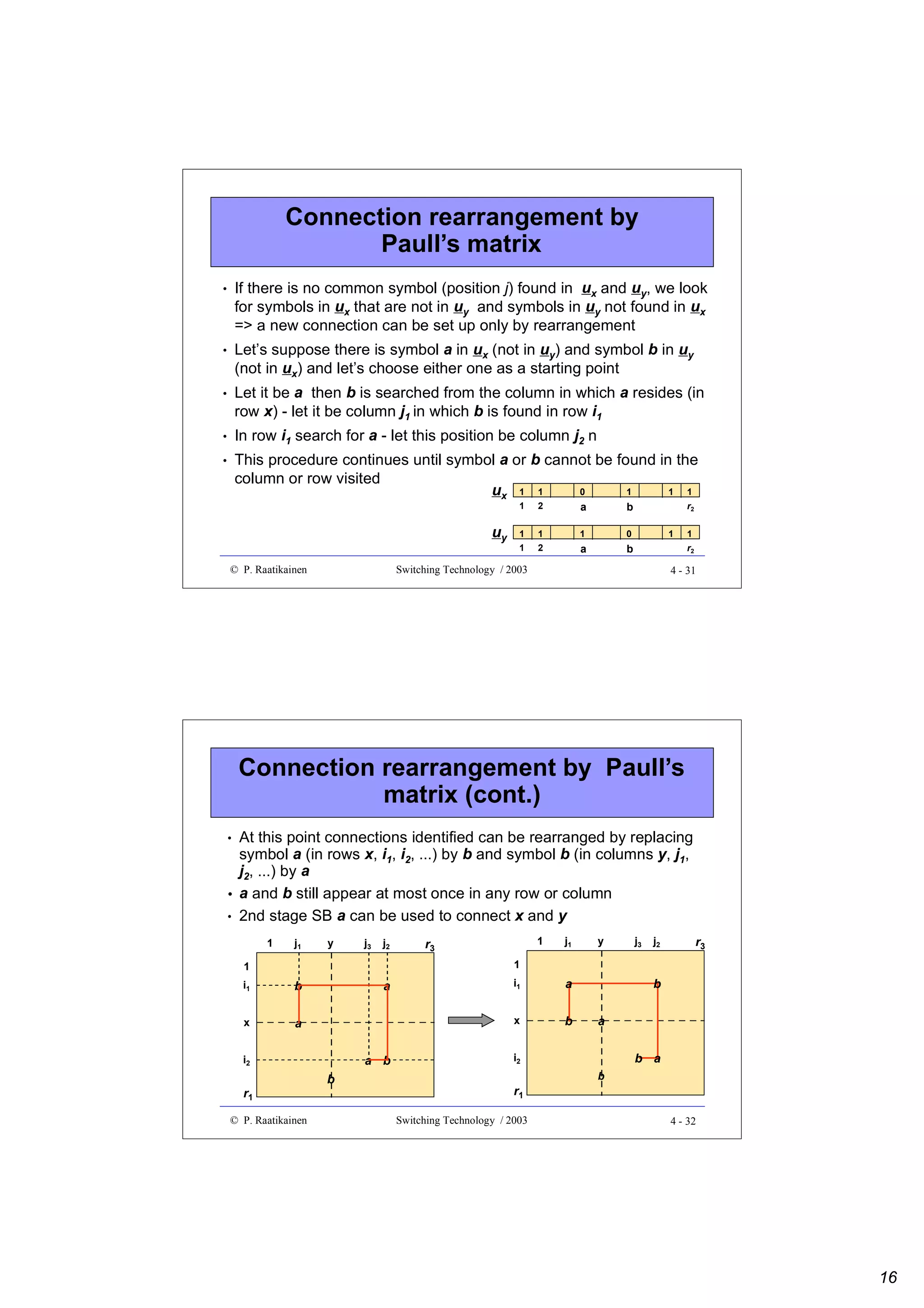

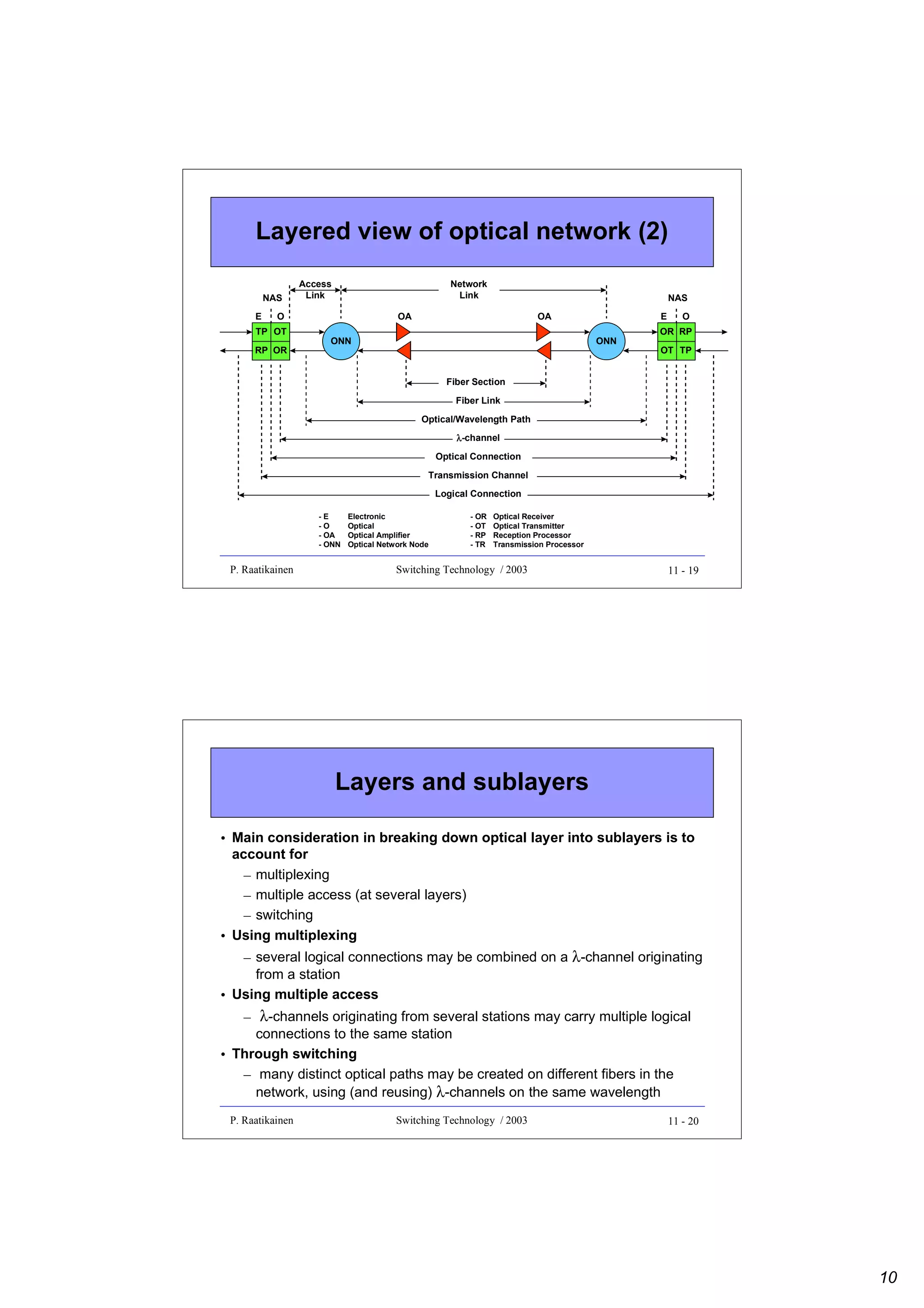

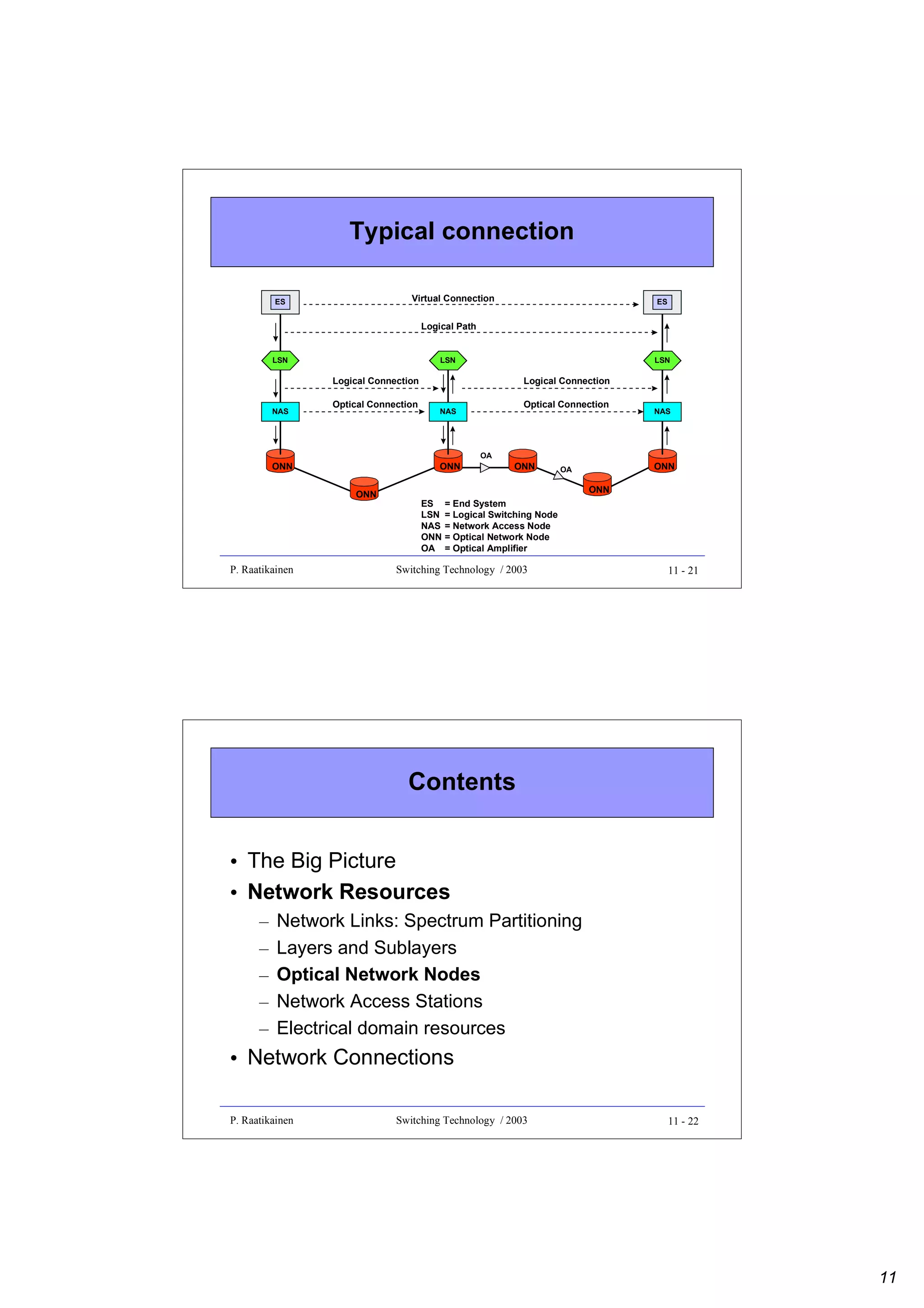

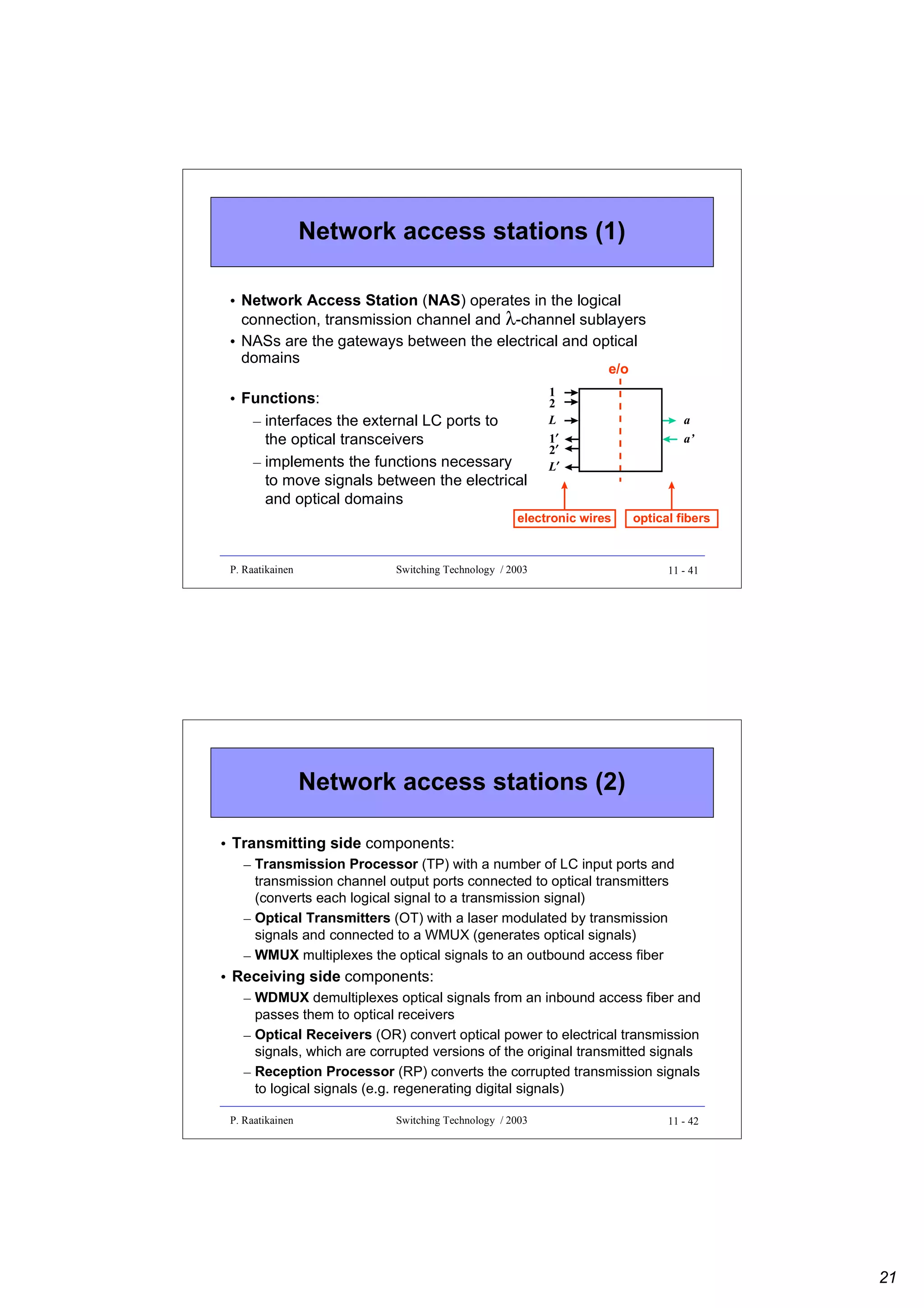

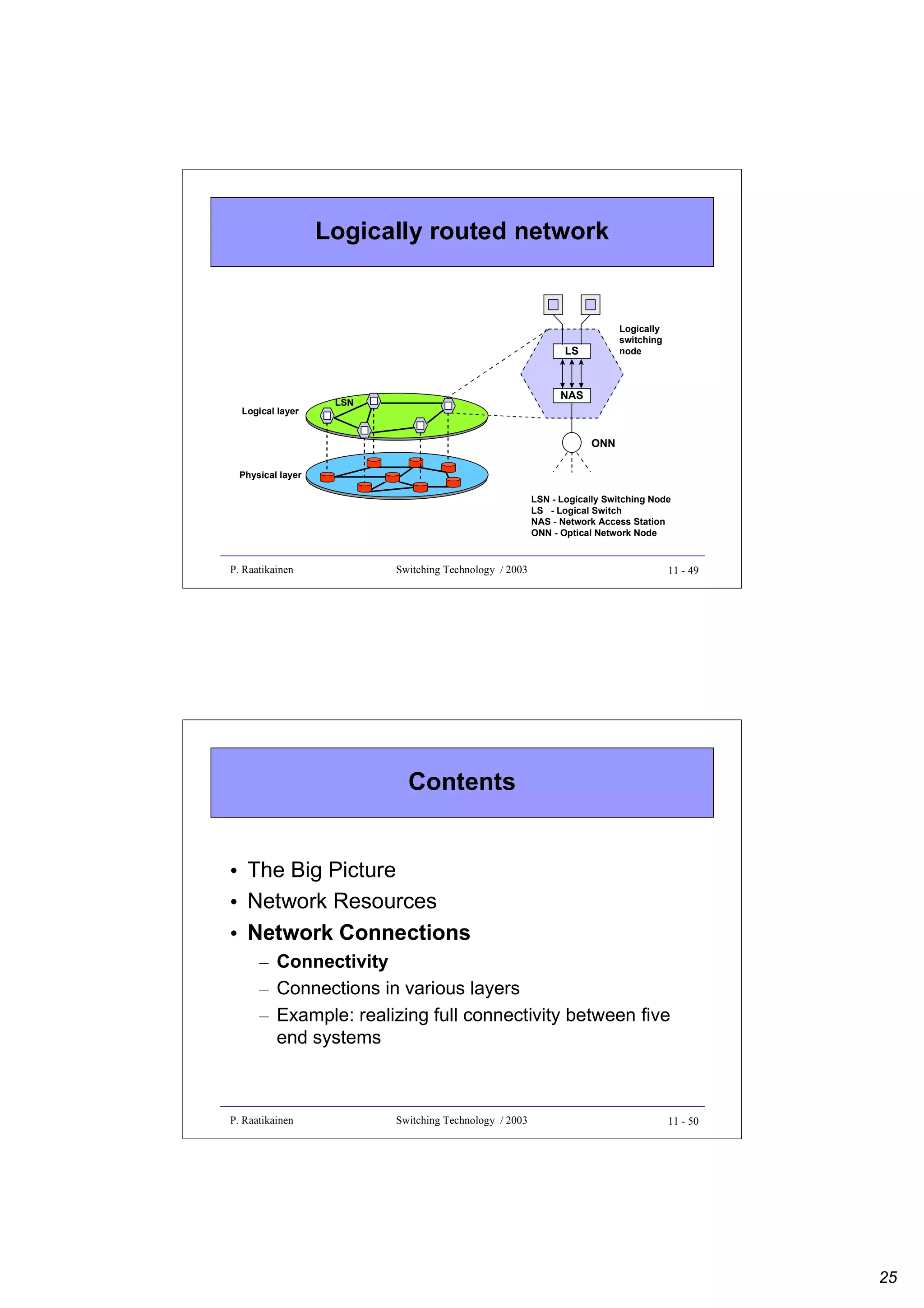

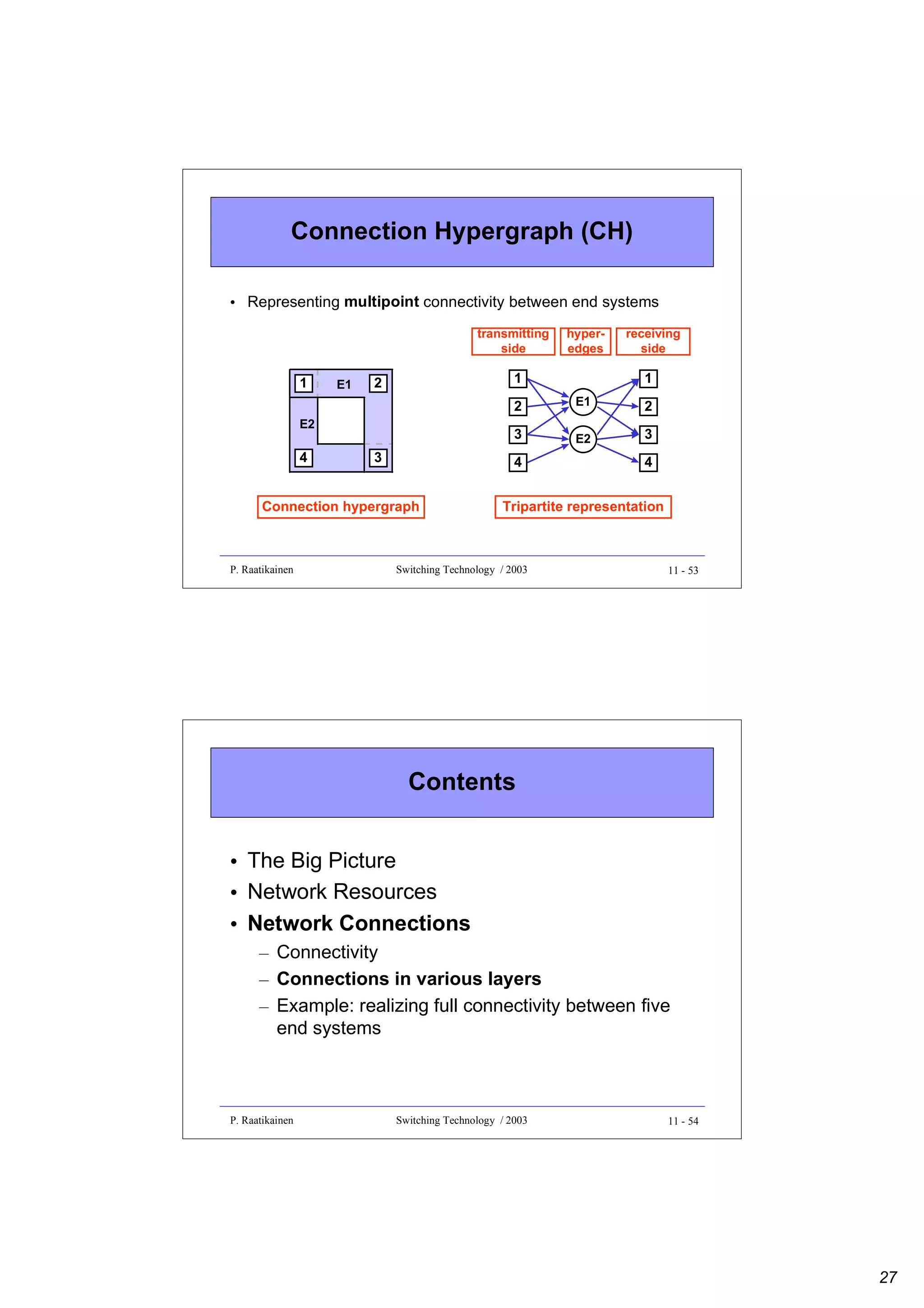

![Connections in various layers

• Logical connection sublayer

– Logical connection (LC) is a unidirectional connection between

external ports on a pair of source and destination network

access stations (NAS)

• Optical connection sublayer

– Optical connection (OC) defines a relation between one

transmitter and one or more receivers, all operating in the same

wavelength

• Optical path sublayer

– Optical path (OP) routes the aggregate power on one waveband

on a fiber, which could originate from several transmitters within

the waveband

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 55

Notation for connections in various

layers

• Logical connection sublayer

– [a, b] = point-to-point logical connection from an external port on station a

to one on station b

– [a, {b, c, …}] = multi-cast logical connection from a to set {b, c, …}

• station a sends the same information to all receiving stations

• Optical connection sublayer

– (a, b) = point-to-point optical connection from station a to station b

– (a, b)k = point-to-point optical connection from a to b using wavelength λk

– (a,{b,c,…}) = multi-cast optical connection from a to set {b,c,…}

• Optical path sublayer

– 〈a, b〉 = point-to-point optical path from station a to station b

– 〈a, b〉k = point-to-point optical path from a to b using waveband wk

– 〈a, {b, c, …}〉 = multi-cast optical path from a to set {b,c,…}

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 56

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-301-2048.jpg)

![Example of a logical connection between

two NASs

Logical connection [A,B]

NAS

NAS

TP

RP

Transmission channel

Electrical

Optical connection (A,B)λ1

OT

Optical

λ-channel

λ1 ... λm

WMUX

Electrical

OR

λm ... λ1

Optical

WDMUX

Optical path <A,B>w1

w1

ONN

w2

P. Raatikainen

ONN

ONN

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 57

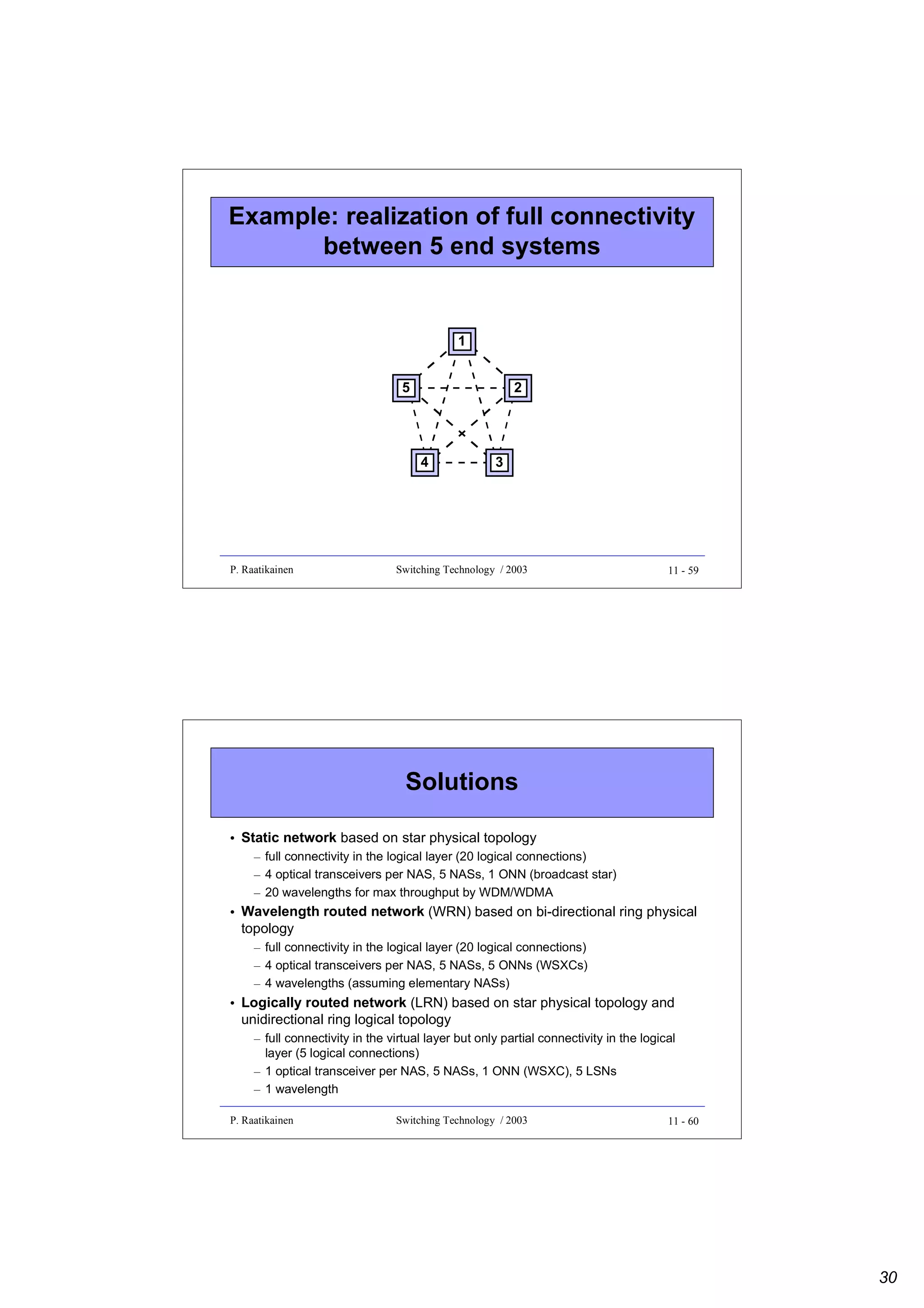

Contents

• The Big Picture

• Network Resources

• Network Connections

– Connectivity

– Connections in various layers

– Example: realizing full connectivity between

five end systems

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

11 - 58

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-302-2048.jpg)

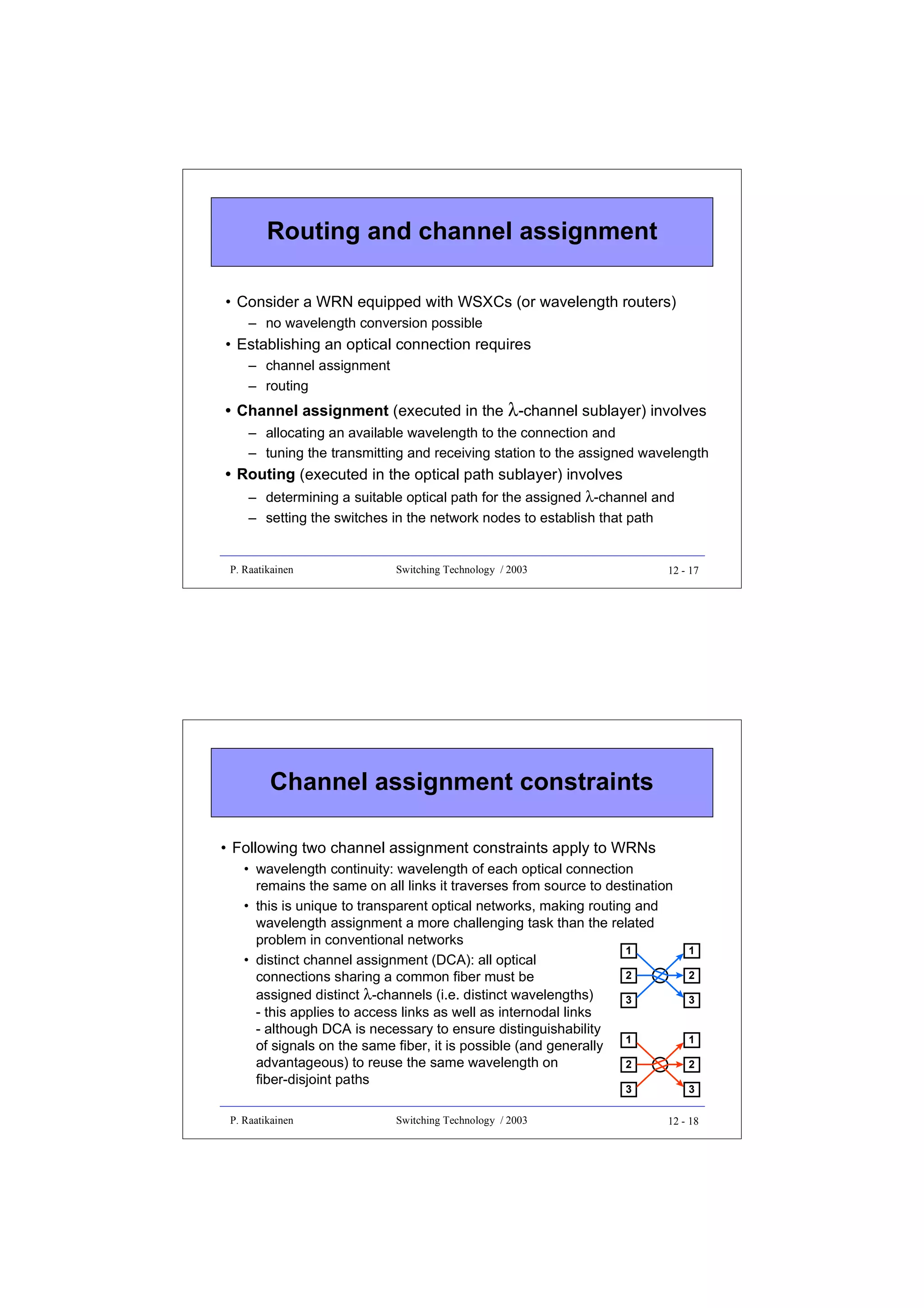

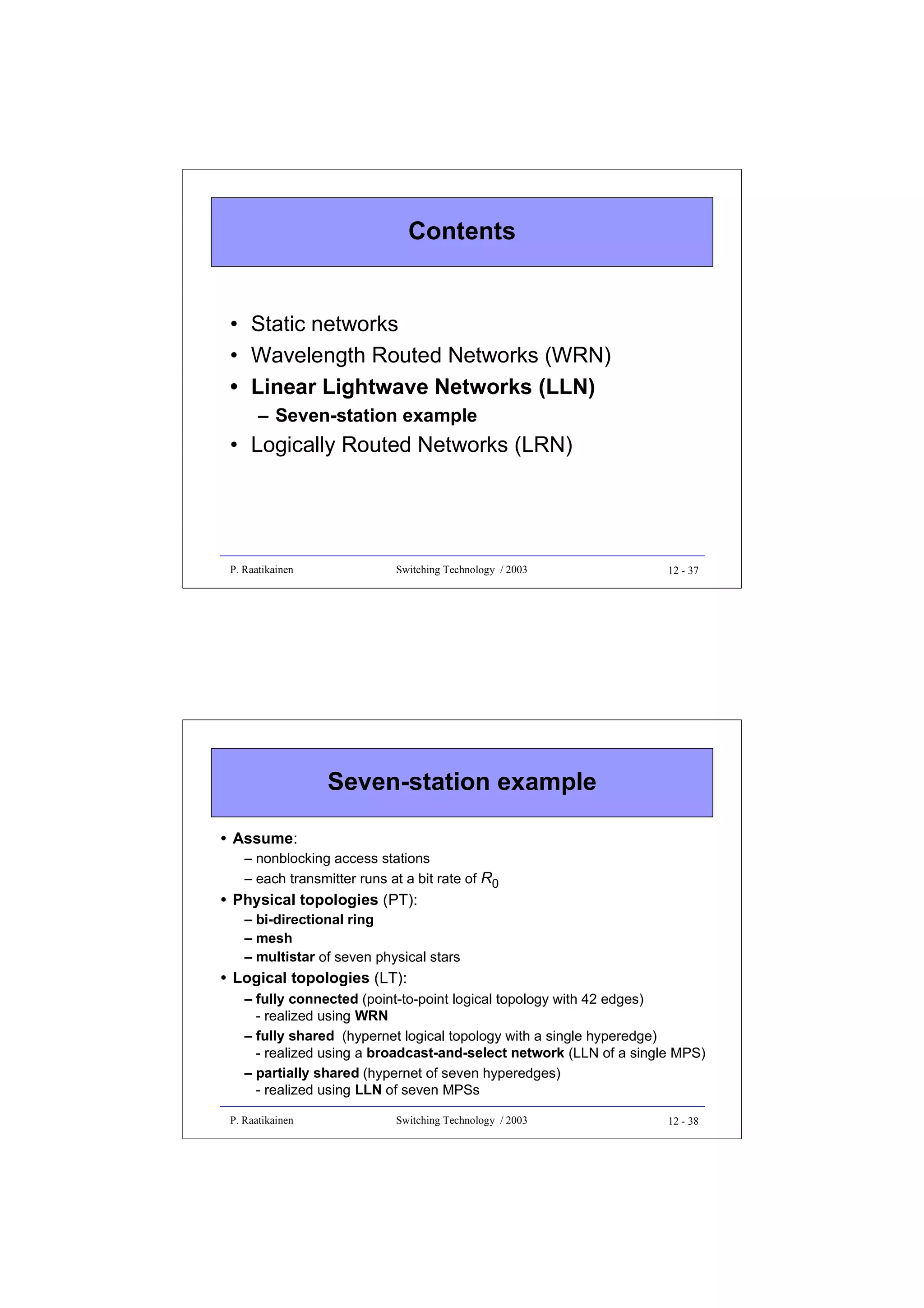

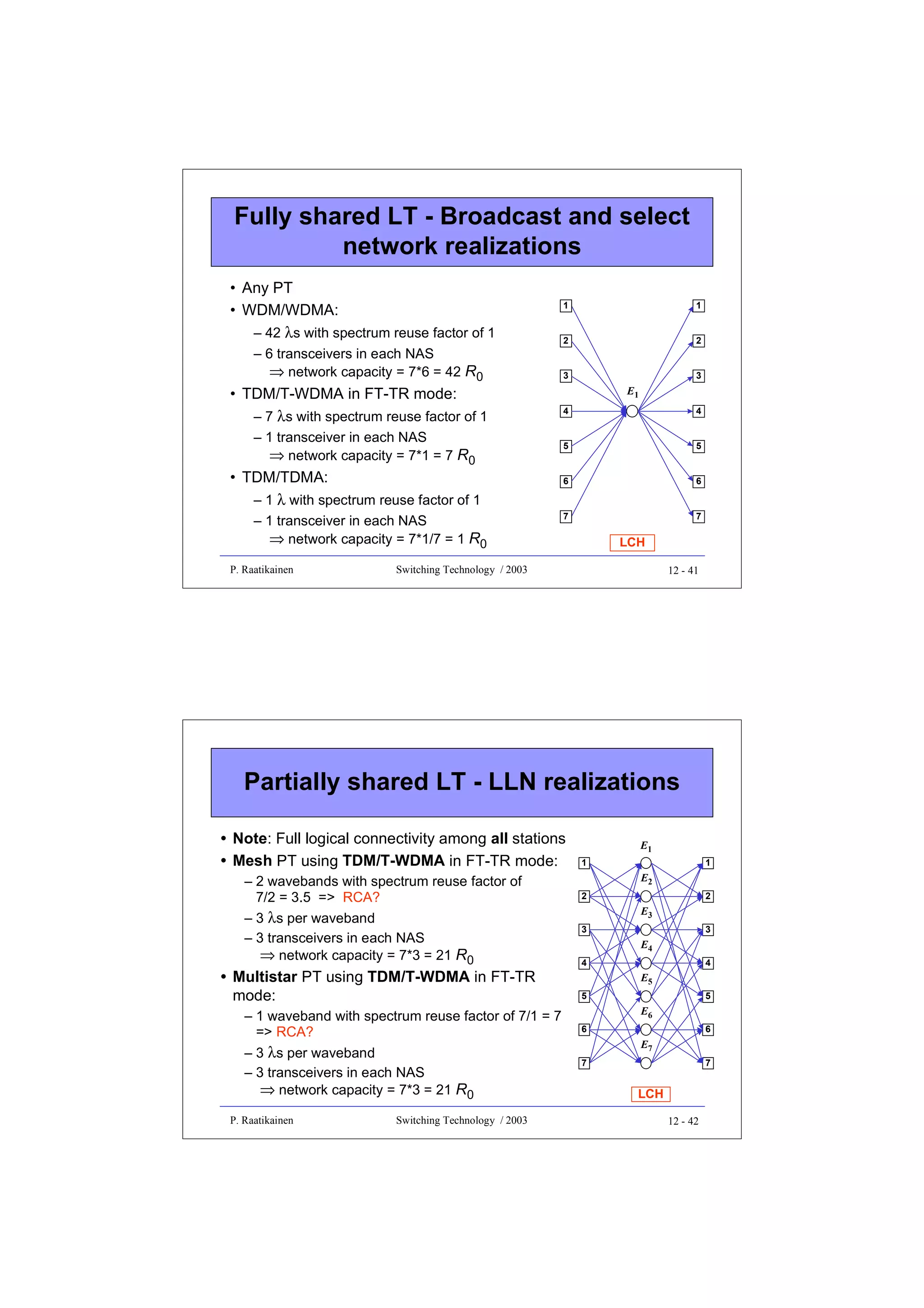

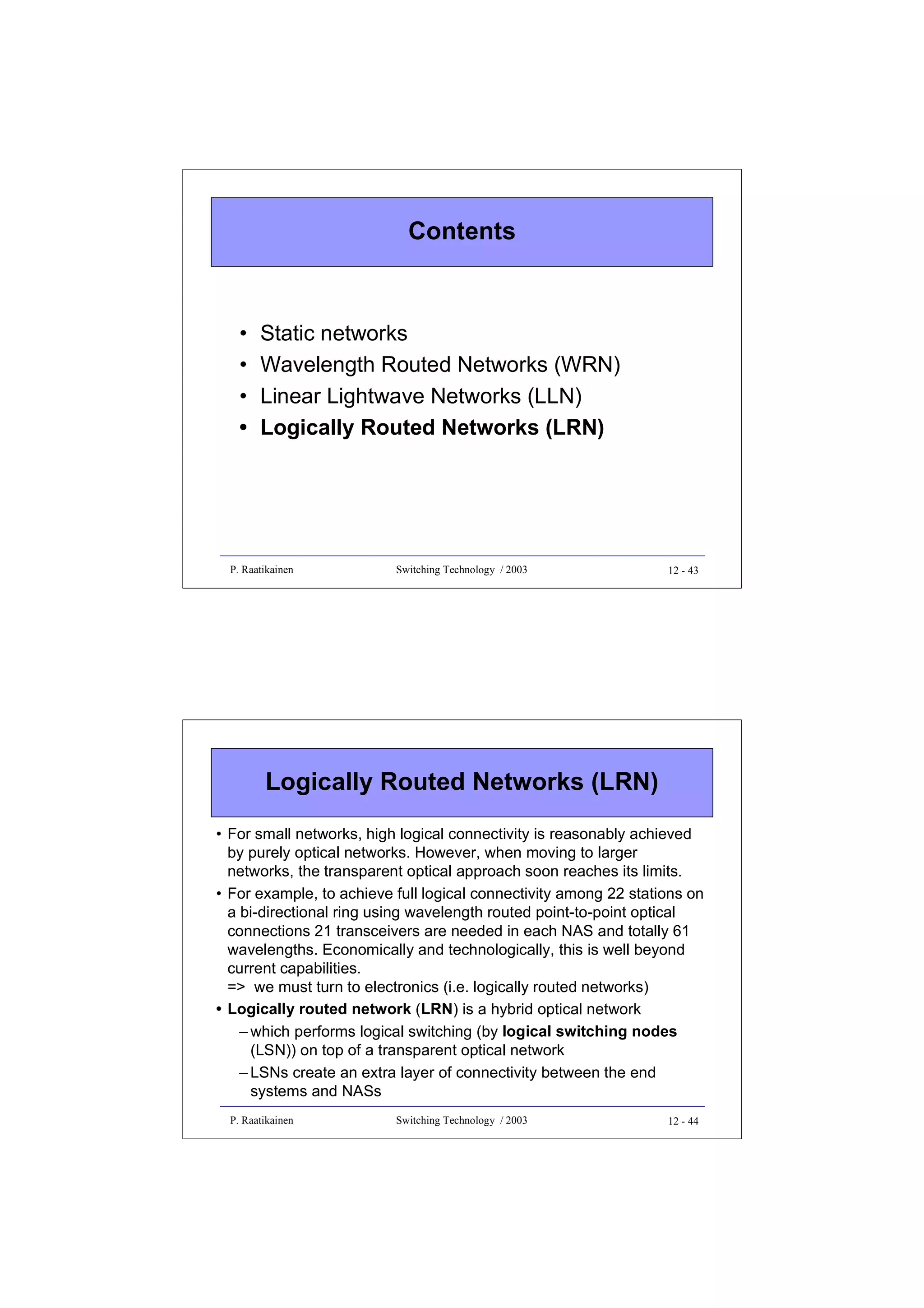

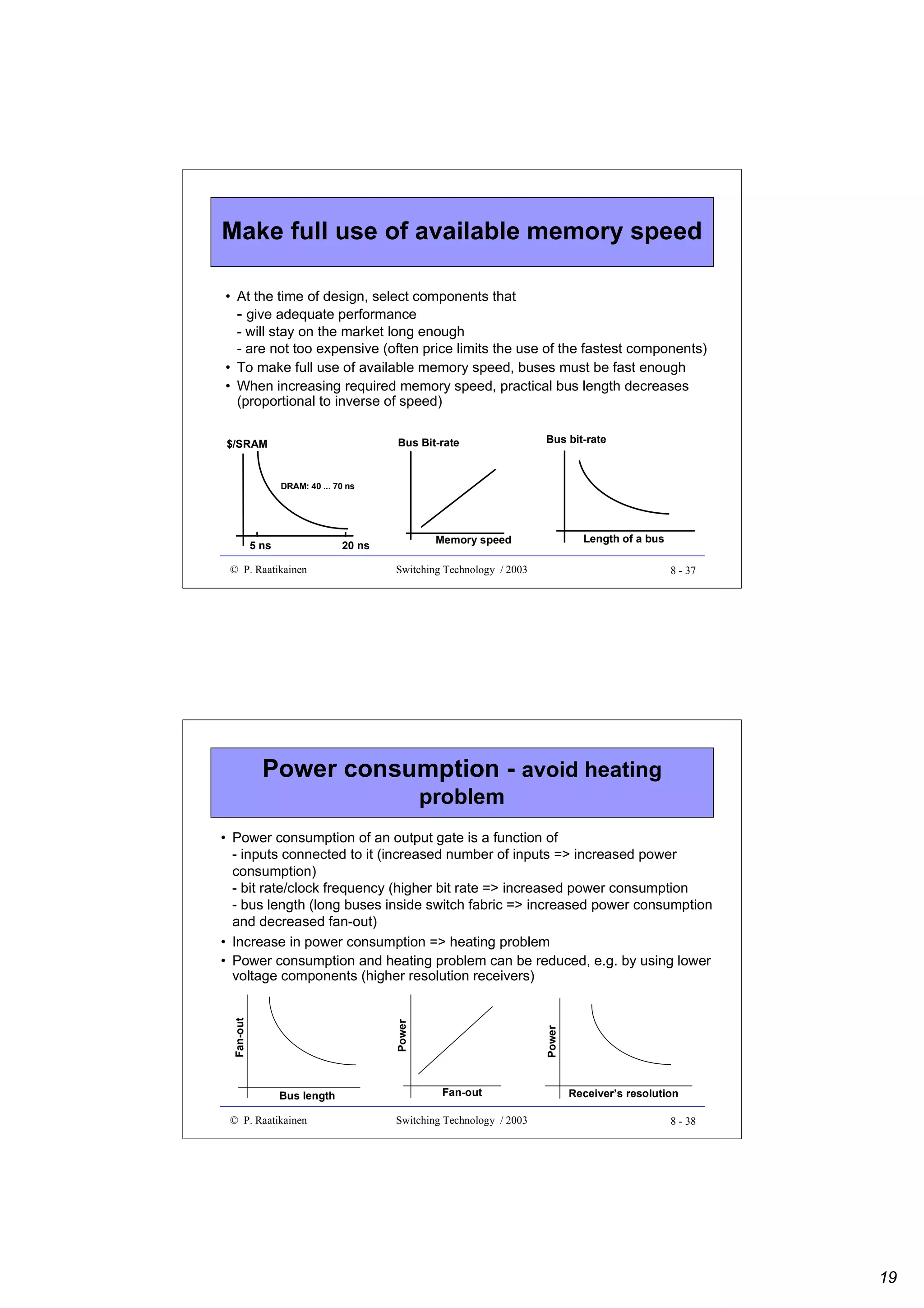

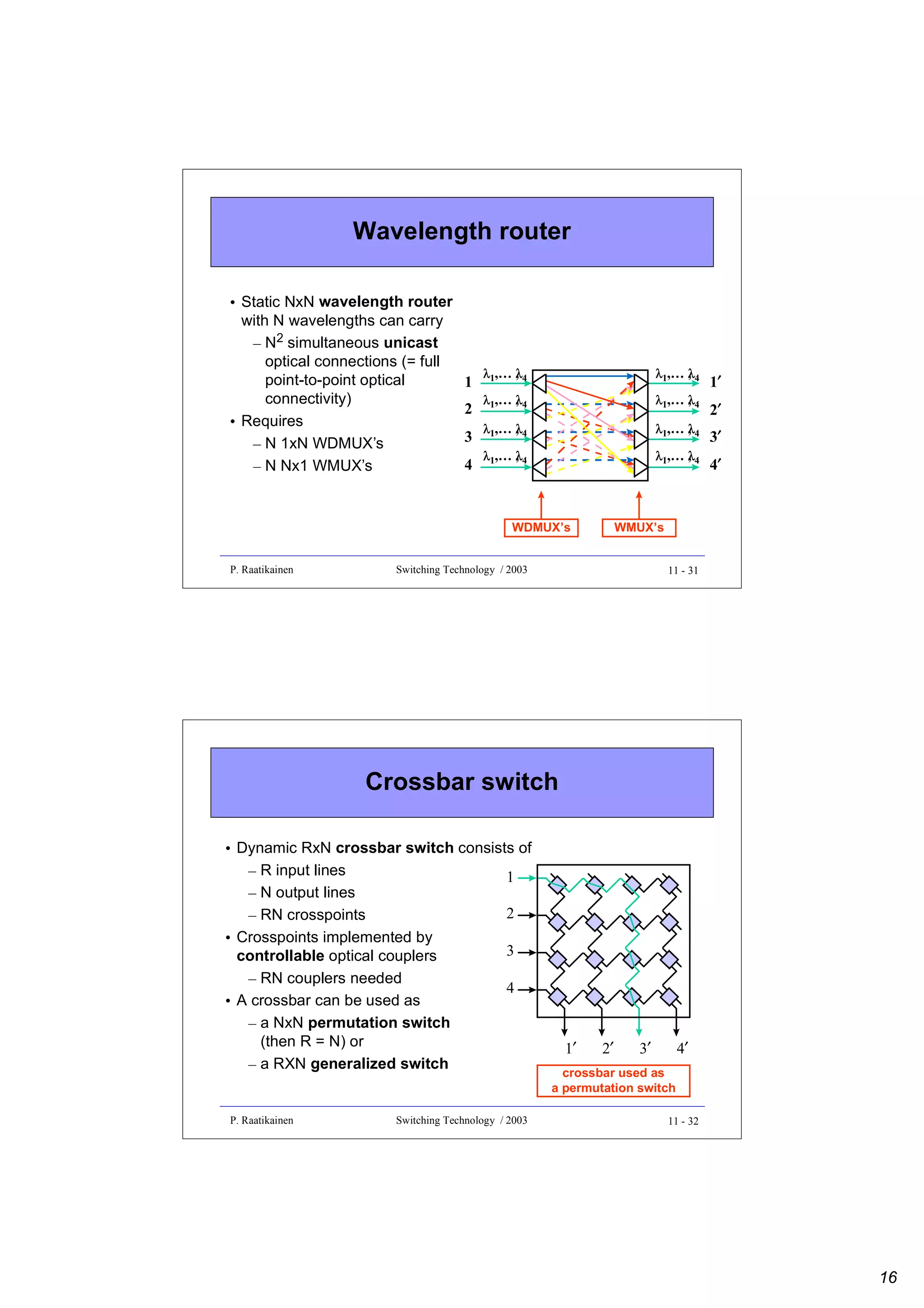

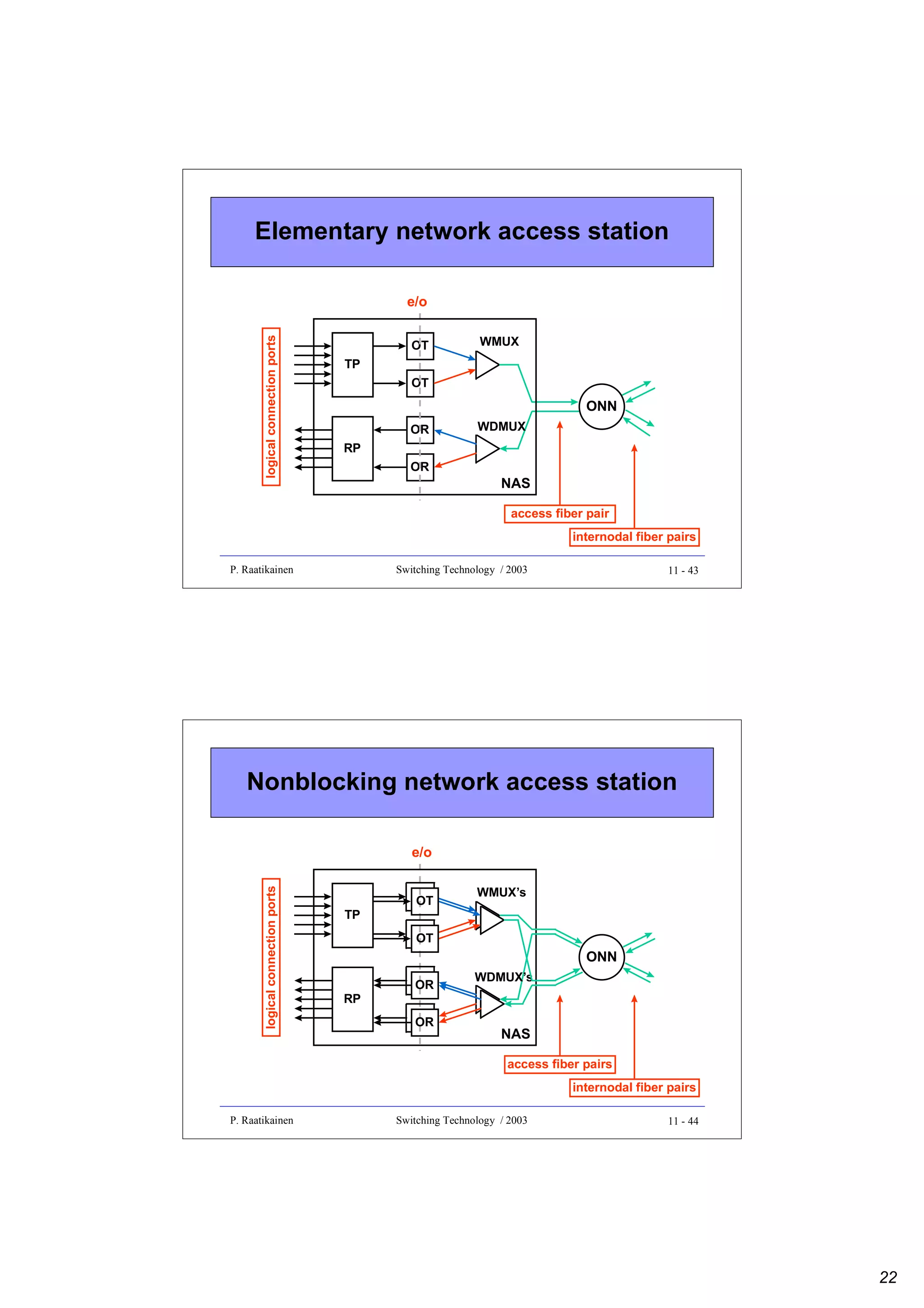

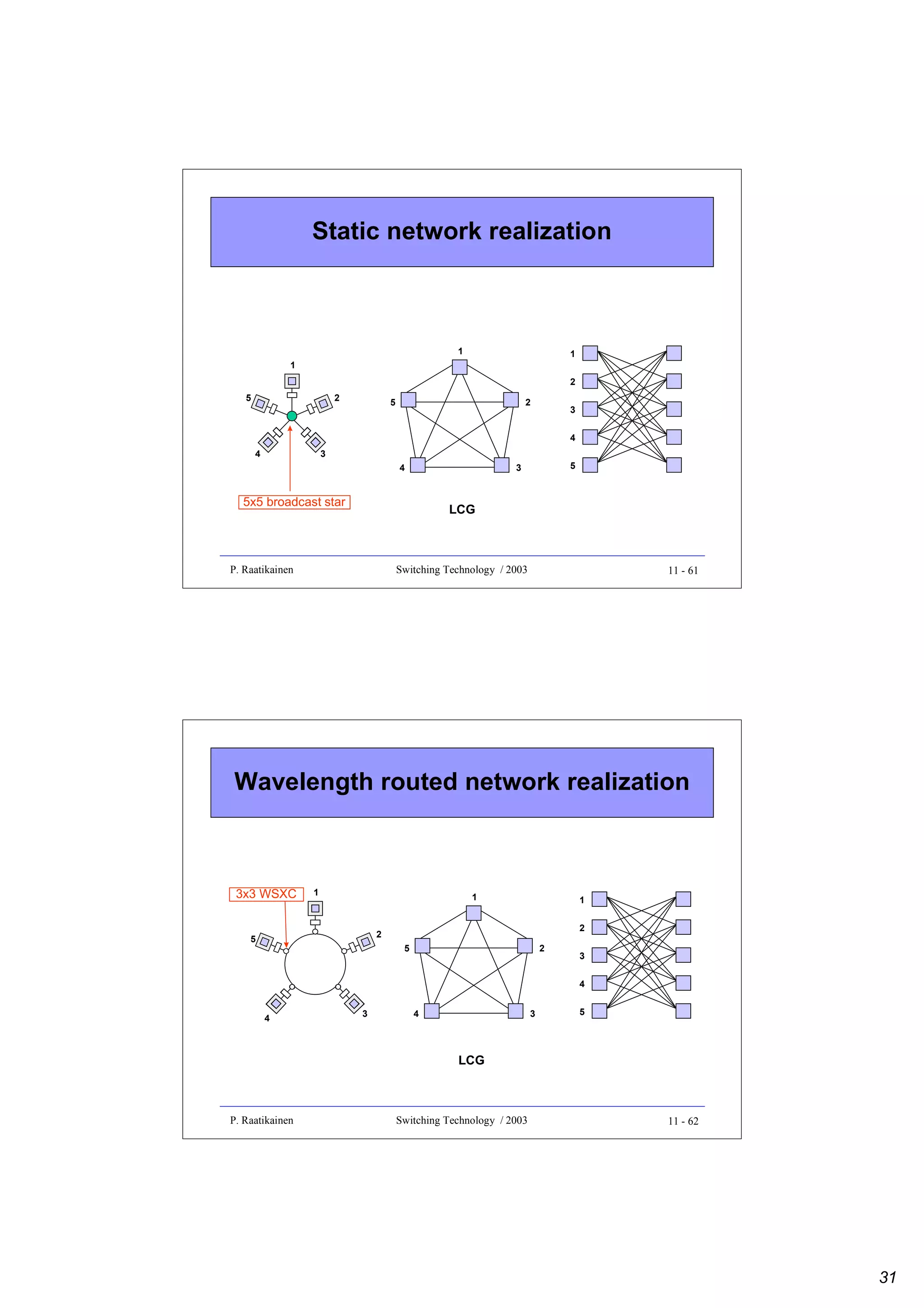

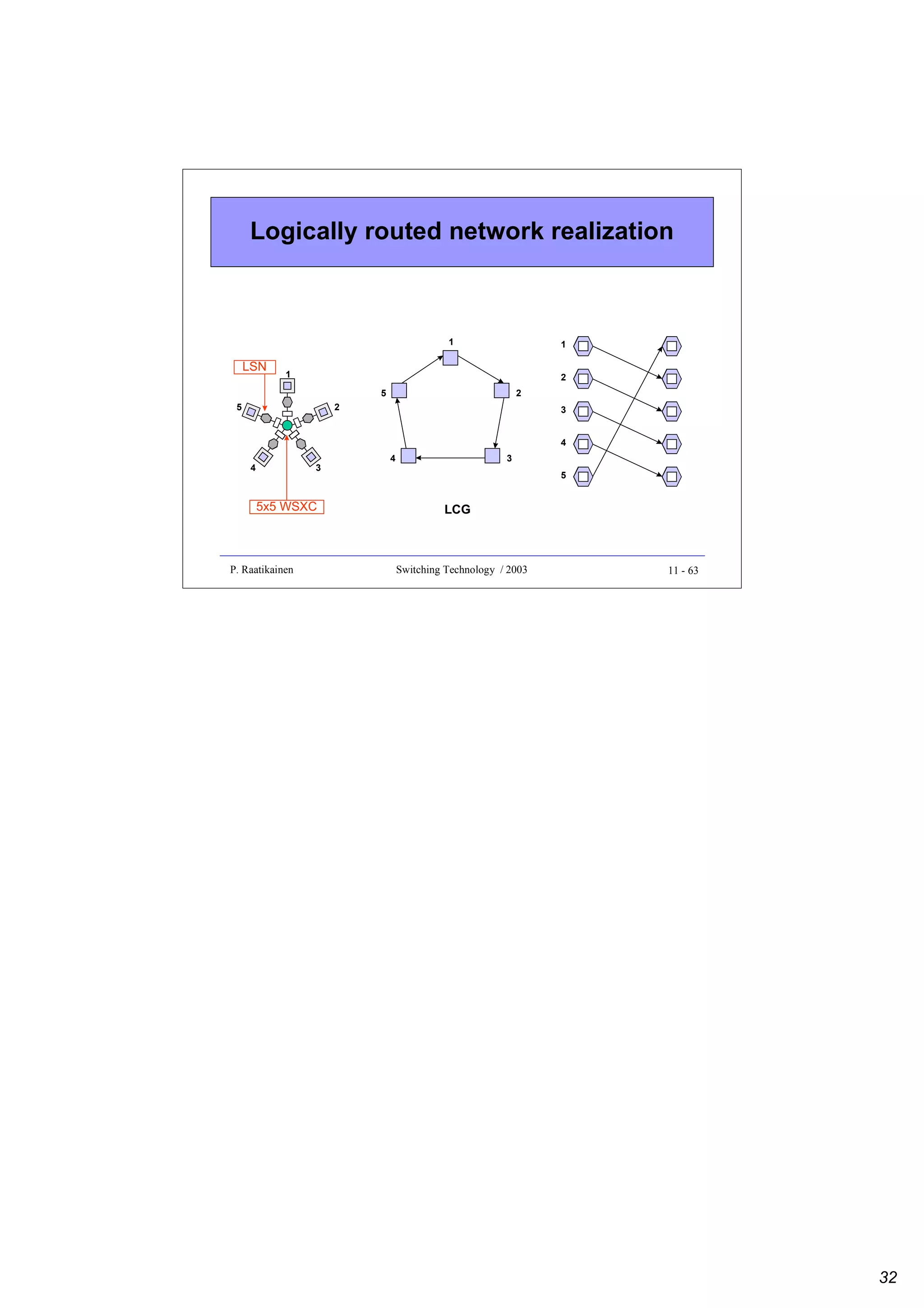

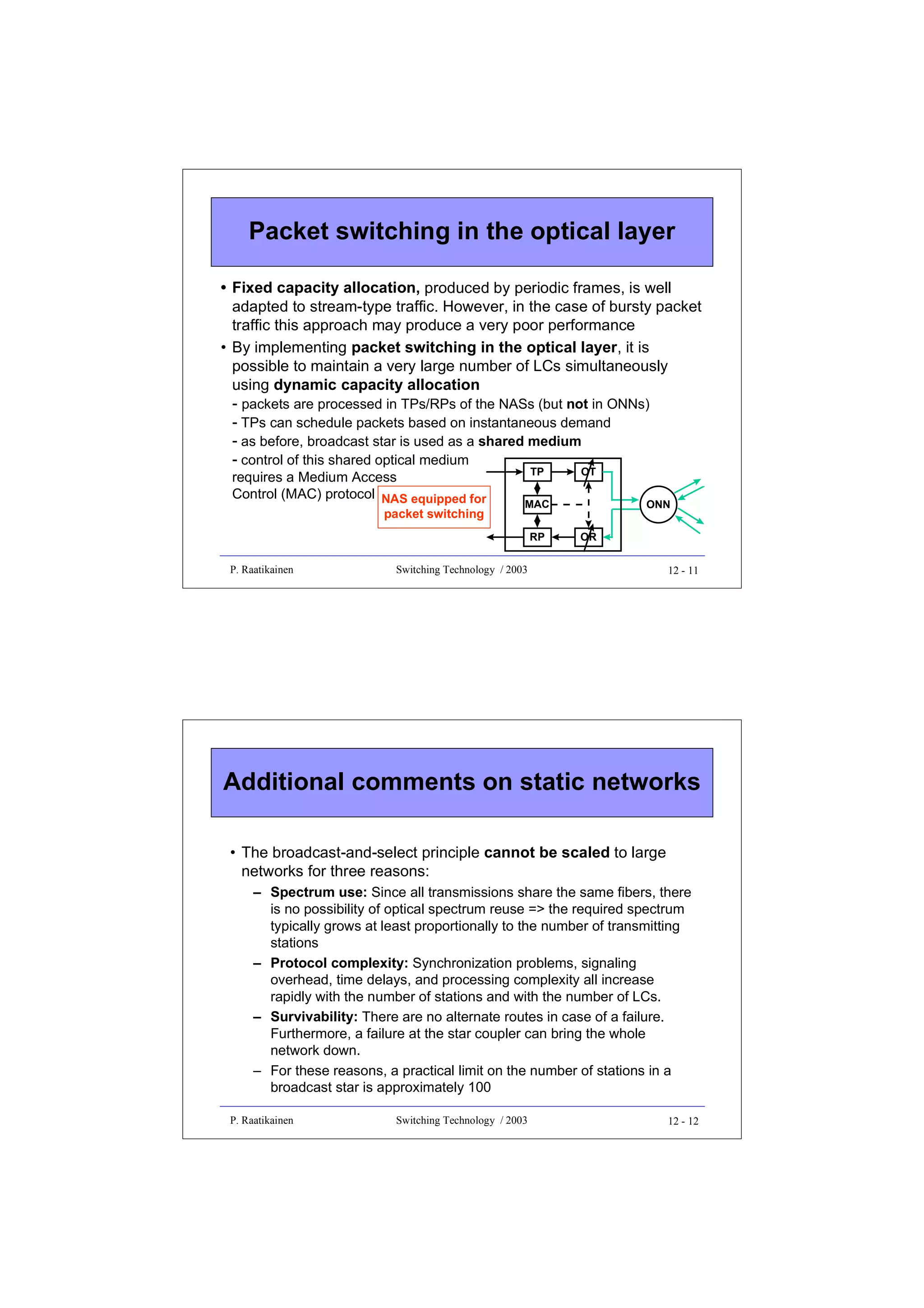

![Static networks

• Static network, also called broadcast-and-select network, is a

purely optical shared medium network

• passive splitting and combining nodes are interconnected by fibers to

provide static connectivity among some or all OTs and ORs

• OTs broadcast and ORs select

• Broadcast star network is an example of such a static network

• star coupler combines all signals and broadcasts them to all ORs

- static optical multi-cast paths from any station to the set of all stations

- no wavelength selectivity at the network node

• optical connection is created by tuning the source OT and/or destination

OR to the same wavelength

• two OTs must operate at different wavelengths (to avoid interference)

- this is called the distinct channel assignment (DCA) constraint

• however, two ORs can be tuned to the same wavelength

- by this way, optical multi-cast connections are created

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 3

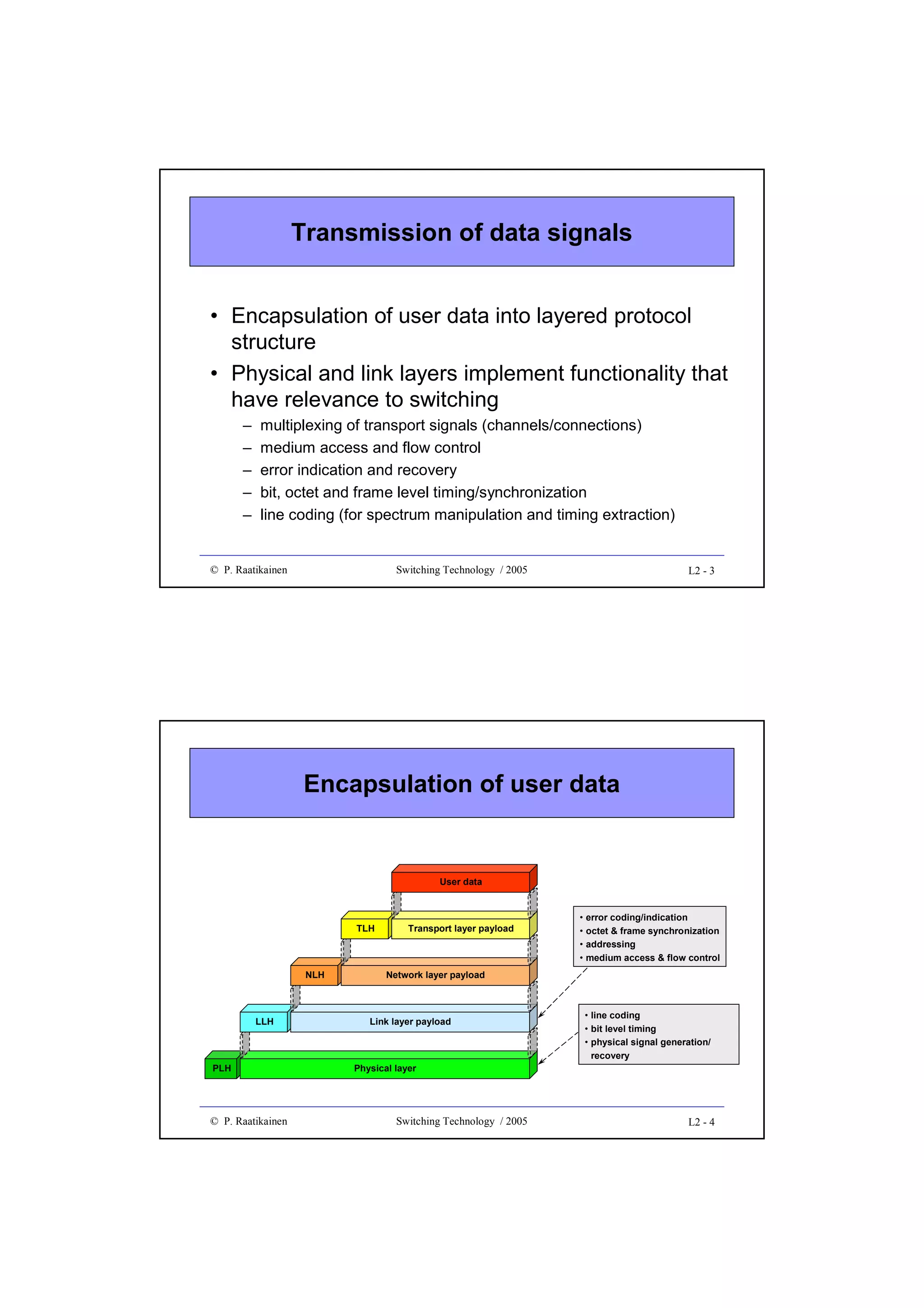

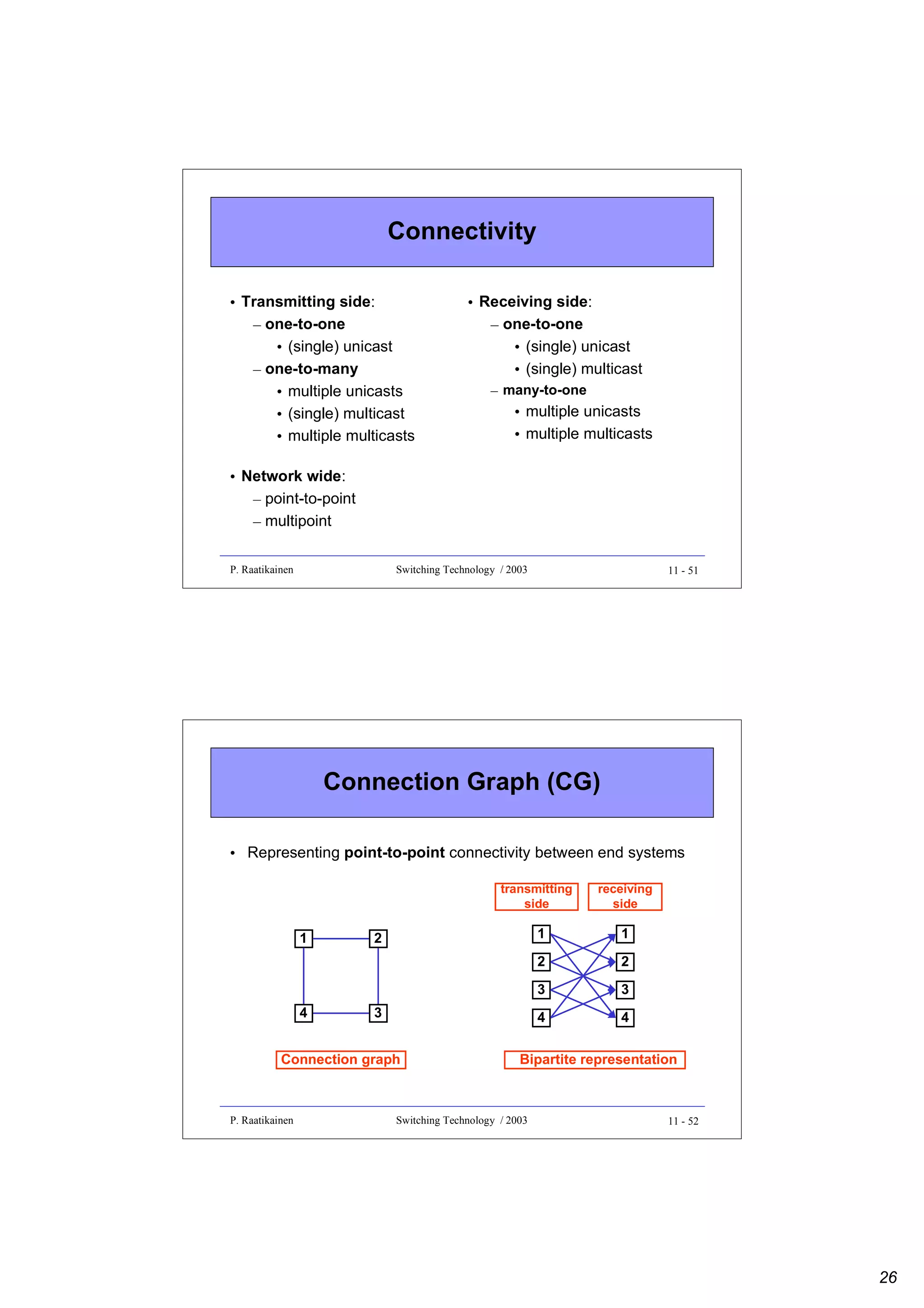

Realization of logical connectivity

• Methods to realize full point-to-point logical connectivity in a

broadcast star with N nodes:

• WDM/WDMA

- a whole λ-channel allocated for each LC

- N(N-1) wavelengths needed (one for each LC)

- N-1 transceivers needed in each NAS

• TDM/TDMA

- 1/[N(N-1)] of a λ-channel allocated for each LC

- 1 wavelength needed

- 1 transceiver needed in each NAS

• TDM/T-WDMA

- 1/(N-1) of a λ-channel allocated for each LC

- N wavelengths needed (one for each OT)

- 1 transceiver needed in each NAS, e.g. fixed OT and tunable OR

(FT-TR), or tunable OT and fixed OR (TT-FR)

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-307-2048.jpg)

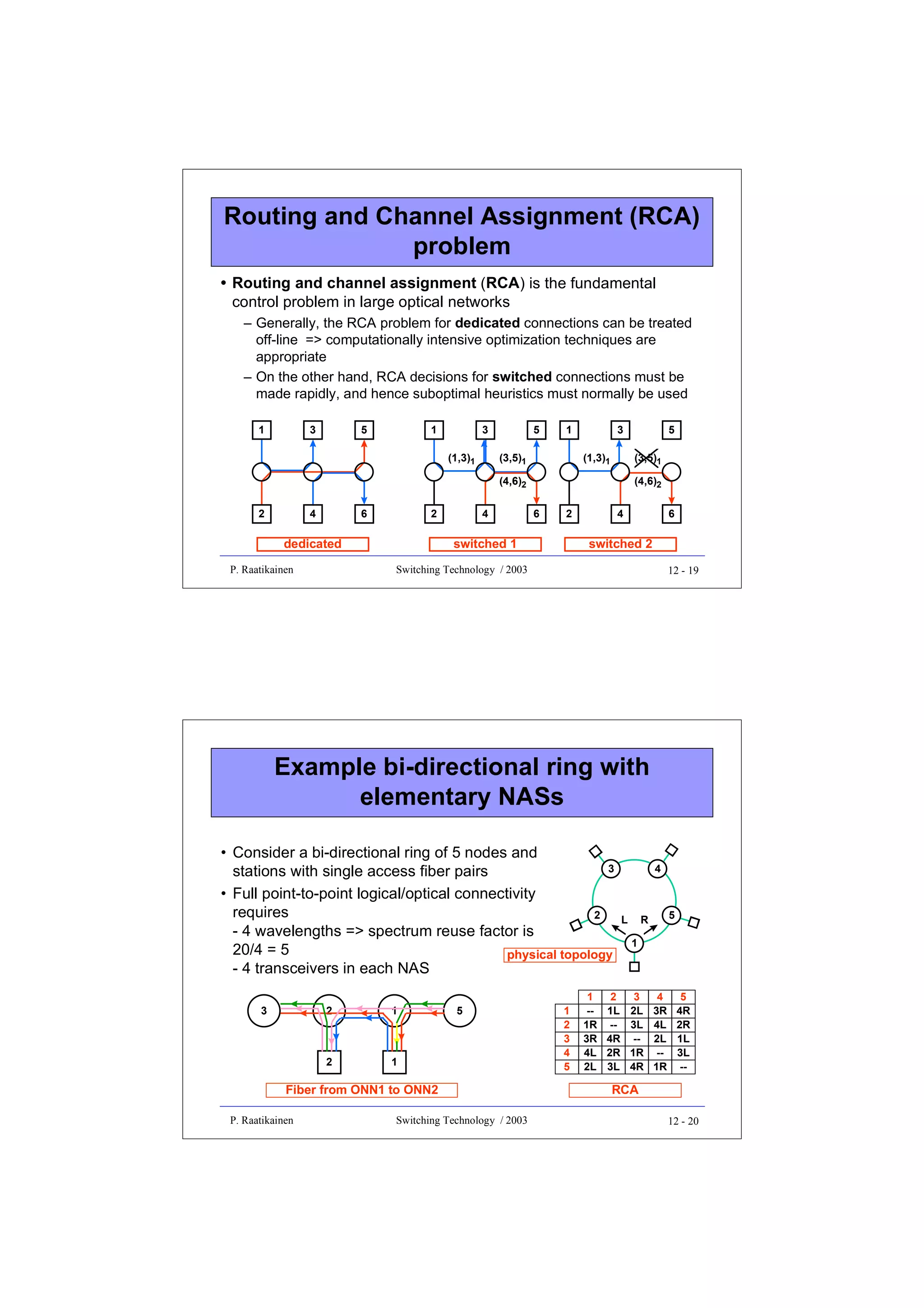

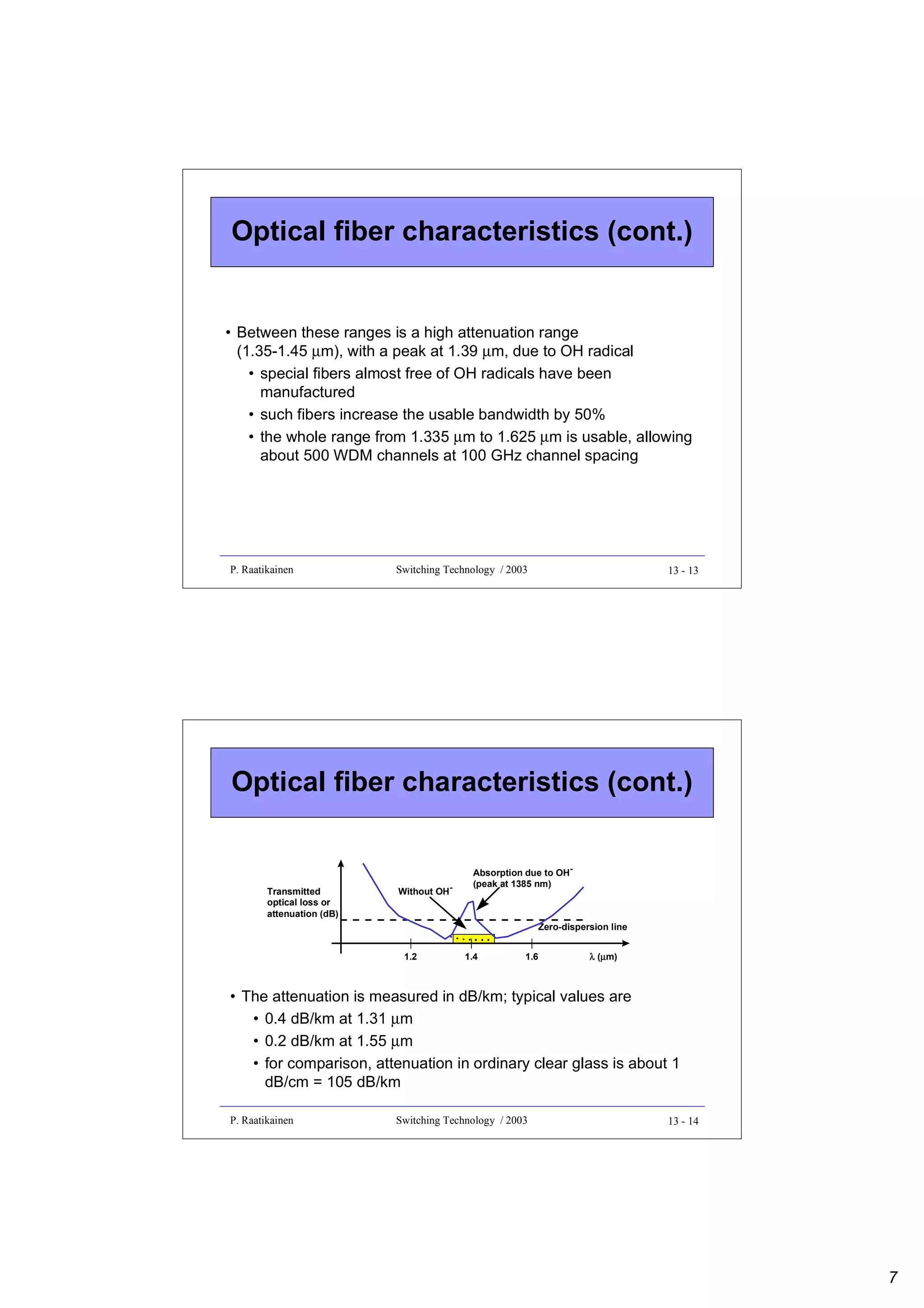

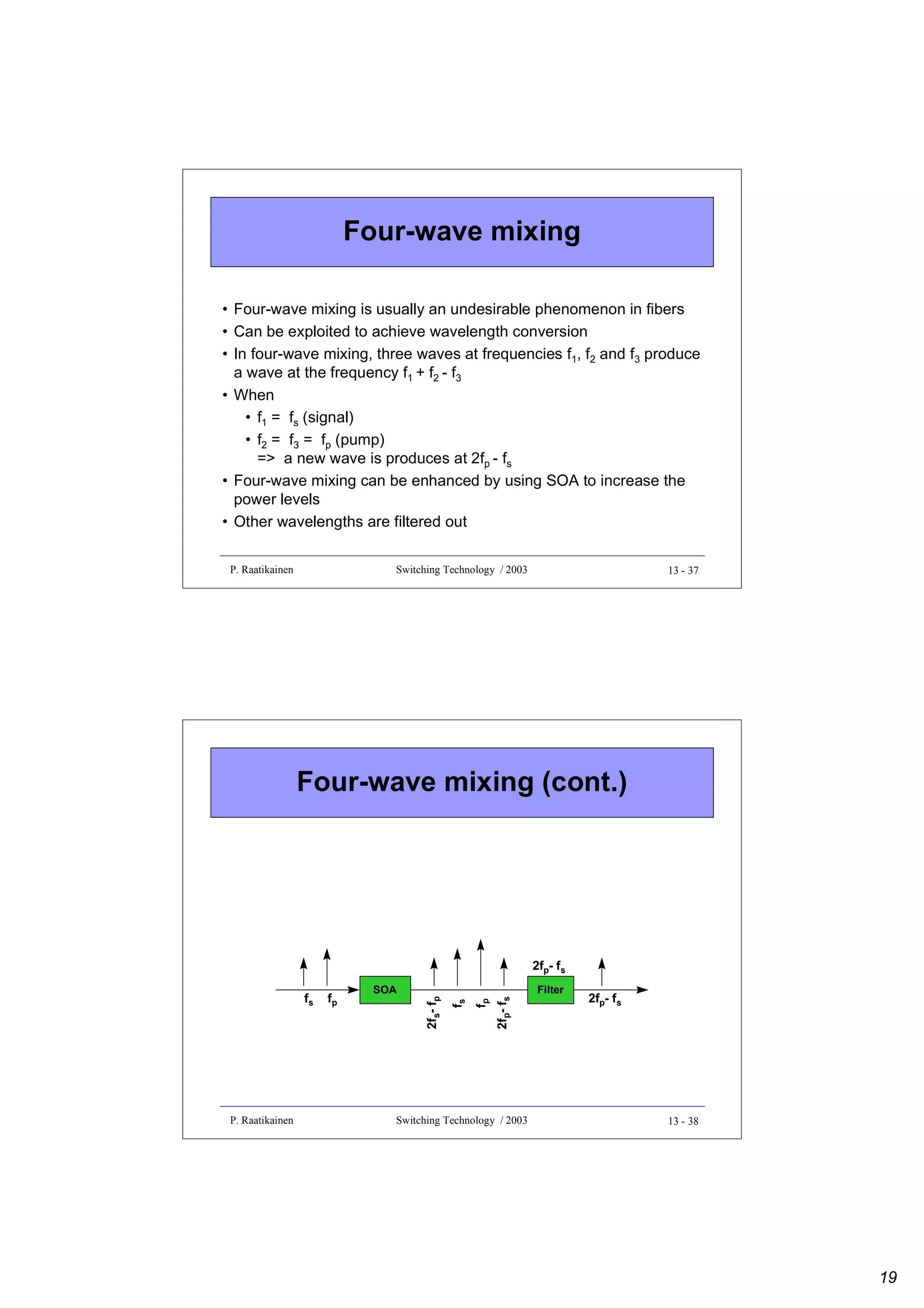

![Broadcast star using WDM/WDMA

LCs

[1,2]

[1,3]

[2,1]

[2,3]

[3,1]

[3,2]

LCs

NAS 1

TP

TP

TP

λ1

OT λ

2

OT

λ3

OT λ

4

OT

λ5

OT λ

6

OT

λ1,2

λ1-6

λ3,4

λ1-6

λ1-6

λ5,6

λ3

λ5 OR

OR

λ1

λ6 OR

OR

λ2

λ4 OR

OR

RP

[2,1]

[3,1]

RP

[1,2]

[3,2]

RP

[1,3]

[2,3]

star coupler

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 5

Broadcast star using TDM/TDMA

LCs

NAS 1

[1,2]

[1,3]

TP

OT

[2,1]

[2,3]

TP

OT

[3,1]

[3,2]

TP

OT

λ1

λ1

λ1

LCs

λ1

λ1

OR

RP

[2,1]

[3,1]

OR

RP

[1,2]

[3,2]

OR

RP

[1,3]

[2,3]

λ1

star coupler

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-308-2048.jpg)

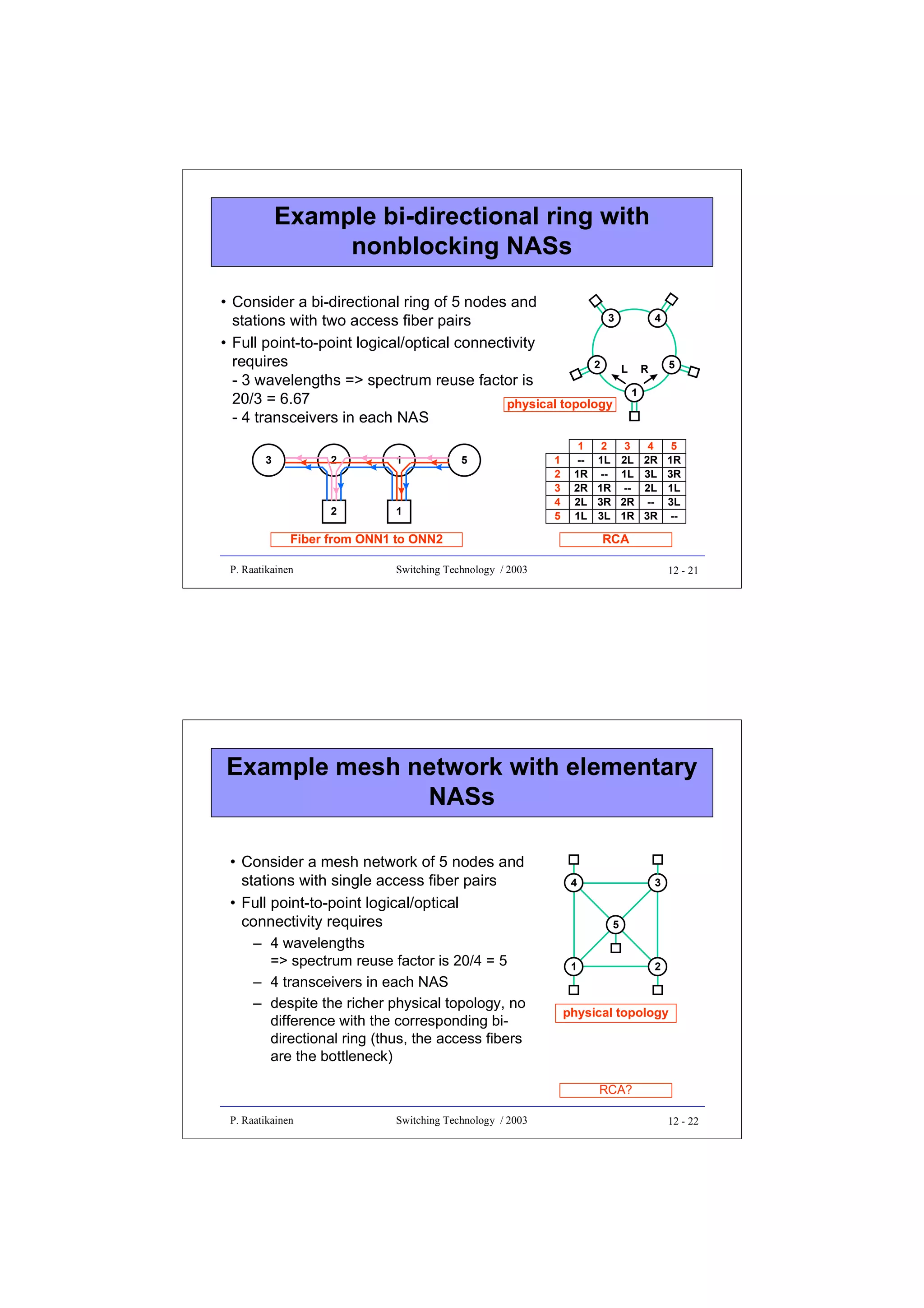

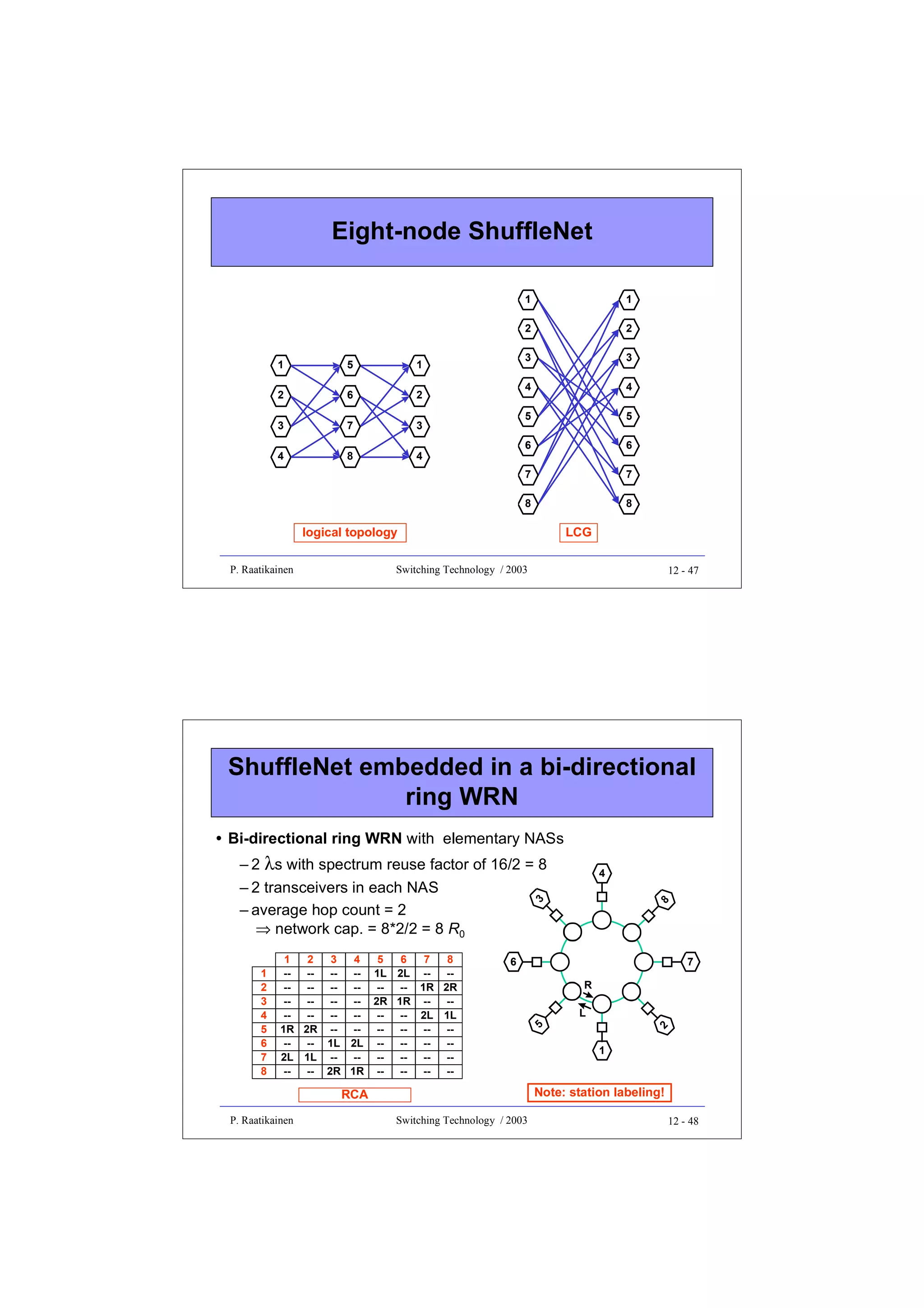

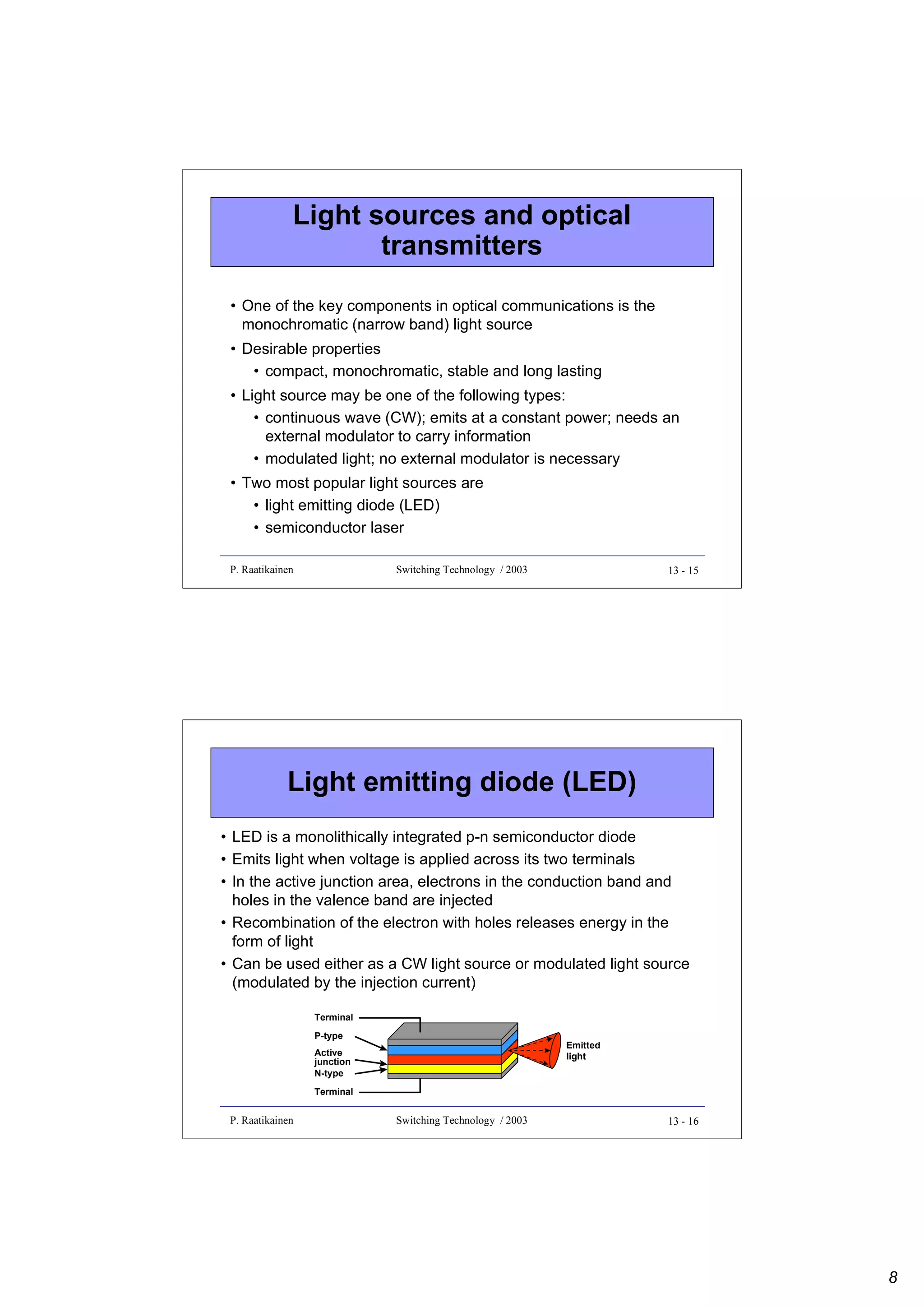

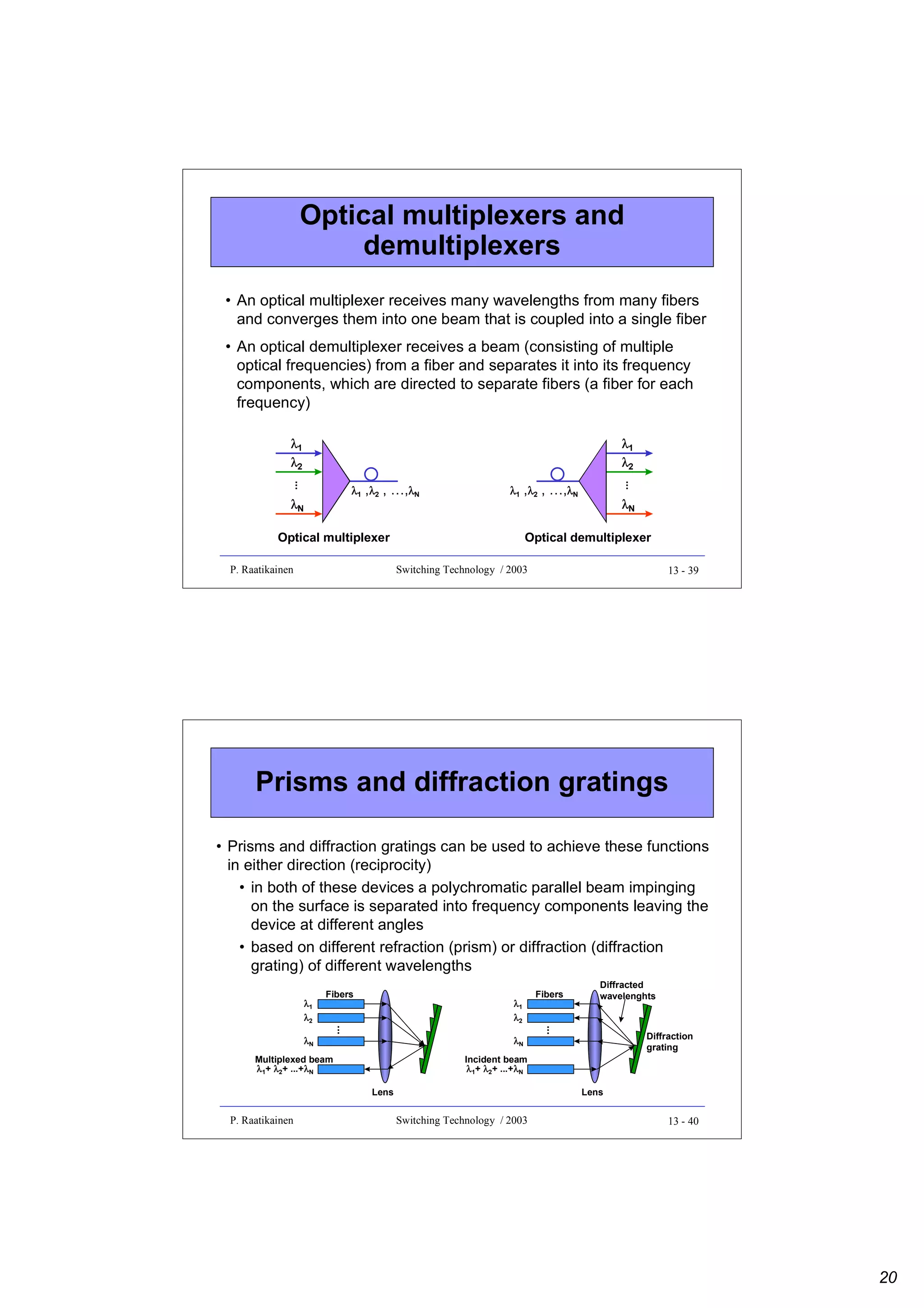

![Effect of propagation delay on

TDM/TDMA

OT1

[1,2]1

[1,2]2

[1,3]1

[1,2]2

From 1

[2,3]2

From 2

From 1

F1

From 2

From 1

F1

From 2

F1

From 2

F2

From 1

P. Raatikainen

From 2

F2

From 1

OR2

OR3

[1,3]1

[2,3]1

OT2

Coupler

[1,2]1

From 1

A TDM/TDMA schedule

From 2

F2

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 7

Broadcast star using TDM/T-WDMA in

FT-TR mode

LCs

fixed

[1,2]

[1,3]

TP

OT

[2,1]

[2,3]

TP

OT

[3,1]

[3,2]

TP

OT

NAS 1

λ1

λ2

λ3

tunable

λ1-3

λ1-3

λ1-3

LCs

λ2

λ3 OR

RP

[2,1]

[3,1]

λ1

λ3 OR

RP

[1,2]

[3,2]

λ1

λ2 OR

RP

[1,3]

[2,3]

star coupler

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-309-2048.jpg)

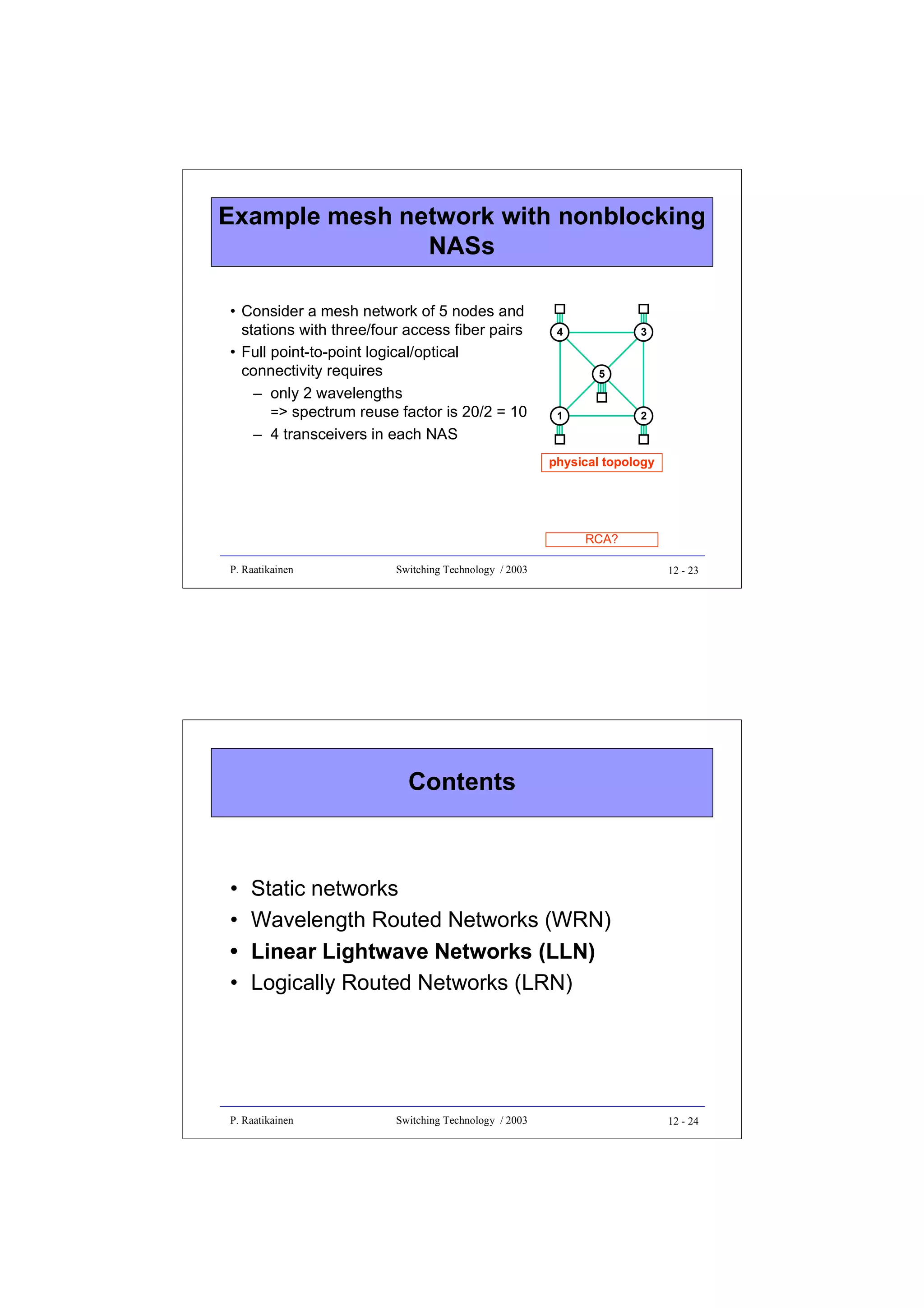

![Broadcast star using TDM/T-WDMA in

TT-FR mode

LCs

[1,2]

[1,3]

[2,1]

[2,3]

[3,1]

[3,2]

tunable

TP

λ2

OT λ3

TP

λ1

OT λ3

TP

λ1

OT λ2

NAS 1

fixed

λ1

λ2,3

λ1,3

λ1,2

λ1-3

λ1-3

λ1-3

λ2

λ3

LCs

OR

RP

[2,1]

[3,1]

OR

RP

[1,2]

[3,2]

OR

RP

[1,3]

[2,3]

star coupler

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 9

Channel allocation schedules for circuit

switching

WDM/WDMA

λ1

λ2

λ3

λ4

[1,2] [1,2] [1,2] [1,2]

[1,3] [1,3] [1,3] [1,3]

[2,1] [2,1] [2,1] [2,1]

TDM/T-WDMA with FT-TR

λ1 [1,2] [1,3] [1,2] [1,3]

λ2 [2,3] [2,1] [2,3] [2,1]

λ3 [3,1] [3,2] [3,1] [3,2]

TDM/T-WDMA with TT-FR

λ1 [2,1] [3,1] [2,1] [3,1]

λ2 [3,2] [1,2] [3,2] [1,2]

λ3 [1,3] [2,3] [1,3] [2,3]

[2,3] [2,3] [2,3] [2,3]

λ5 [3,1] [3,1] [3,1] [3,1]

λ6 [3,2] [3,2] [3,2] [3,2]

frame

TDM/TDMA

frame

frame

Channel allocation schedule (CAS) should be

- realizable = only one LC per each OT and time-slot

- collision-free = only one LC per each λ and time-slot

- conflict-free = only one LC per each OR and time-slot

λ1 [1,2] [1,3] [2,1] [2,3] [3,1] [3,2] [1,2] [1,3] [2,1] [2,3] [3,1] [3,2]

frame

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-310-2048.jpg)

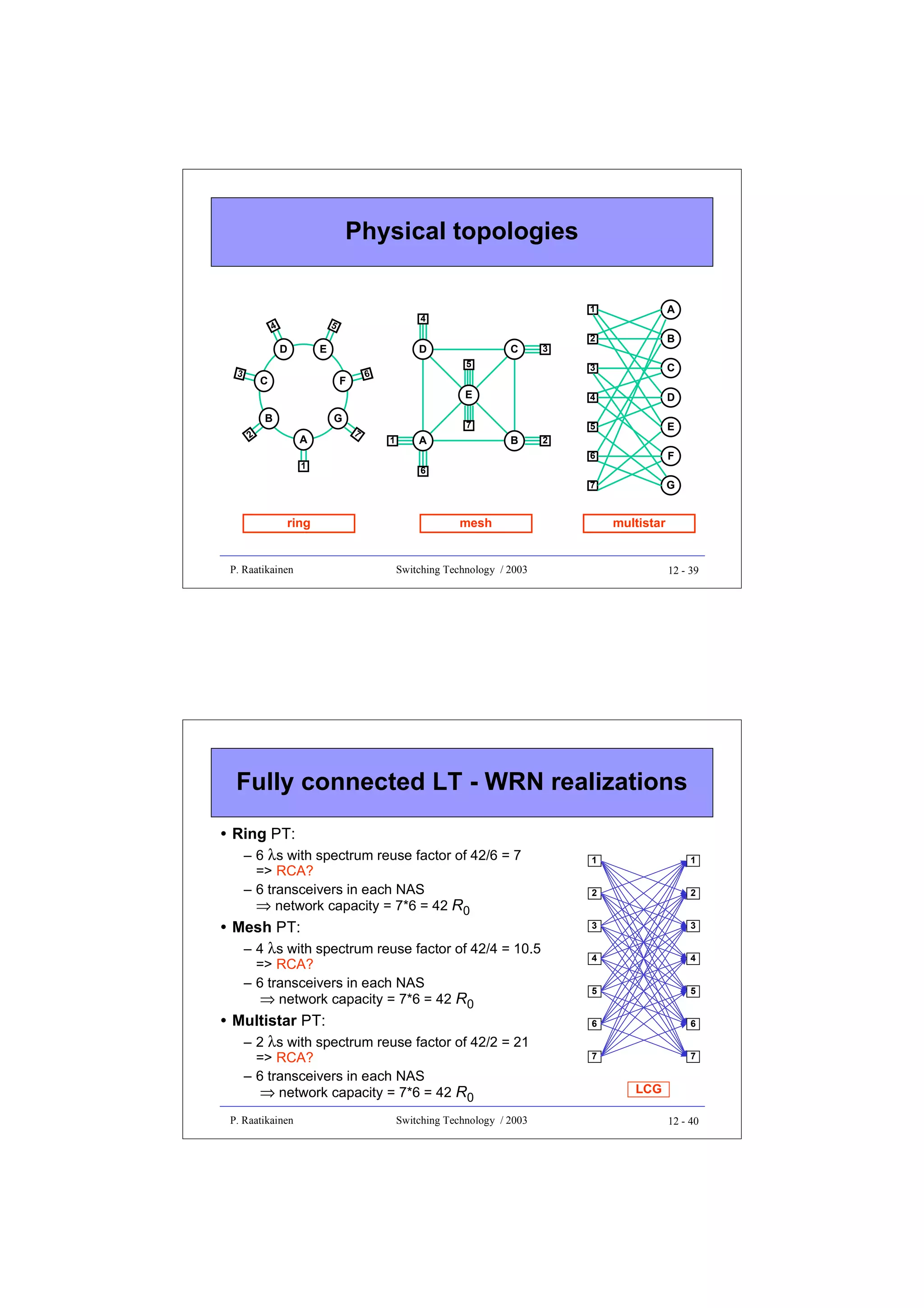

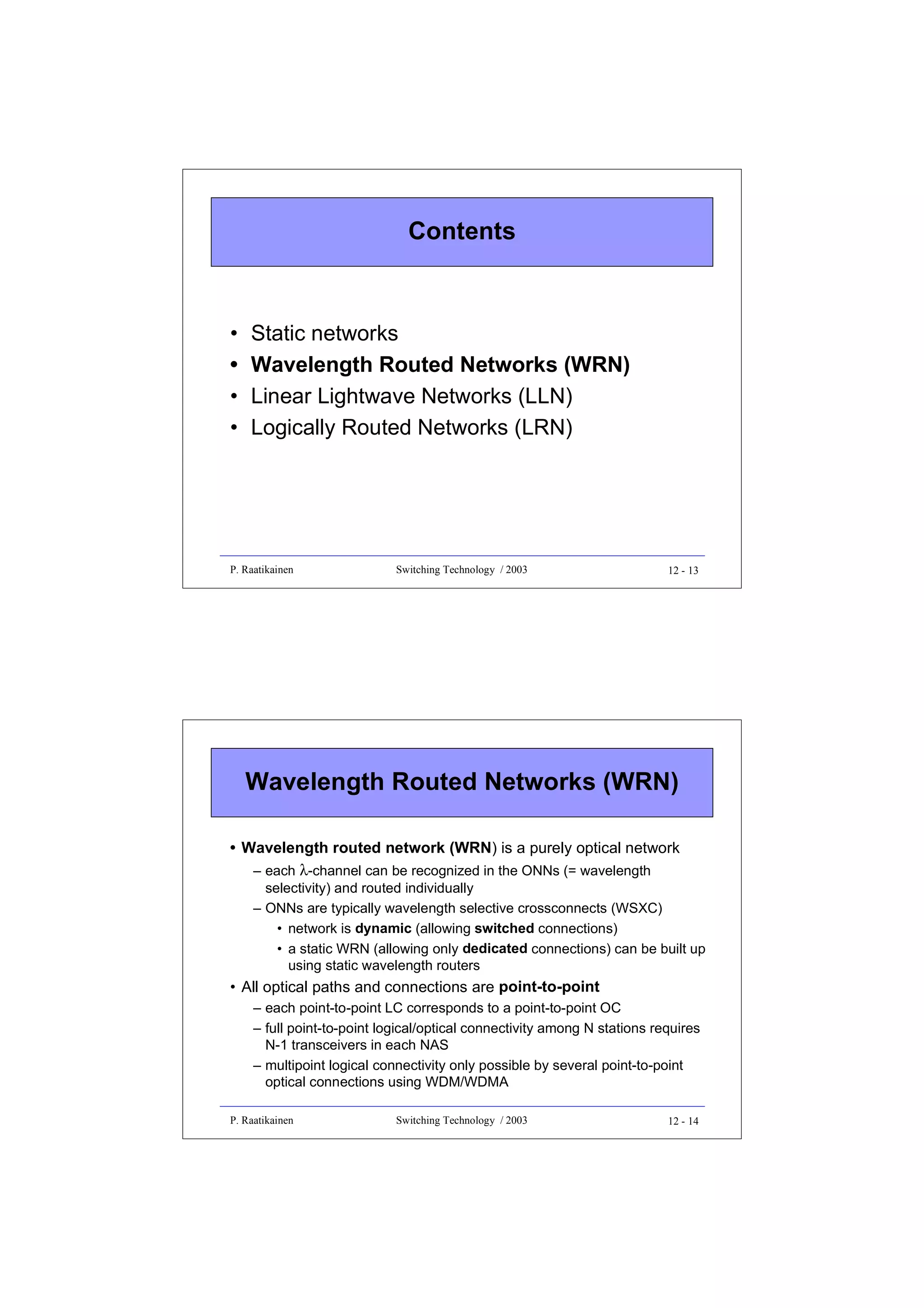

![Static wavelength routed star

• Full point-to-point logical/optical connectivity in a static

wavelength routed star with N nodes can be realized by

– WDM/WDMA

• a whole λ-channel allocated for each LC

• N-1 wavelengths needed

- spectrum reuse factor is N

(= N(N-1) optical connections / N-1 wavelengths)

• N-1 transceivers needed in each NAS

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 15

Static wavelength routed star using

WDM/WDMA

LCs

NAS 1

[1,2]

[1,3]

TP

[2,1]

[2,3]

TP

[3,1]

[3,2]

TP

λ1

OT λ

2

OT

λ2

OT λ

1

OT

λ1

OT λ

2

OT

λ1,2

λ1,2

λ1,2

LC’

λ1,2

λ1,2

λ1,2

λ2

λ1 OR

OR

λ1

λ2 OR

OR

λ2

λ1 OR

OR

RP

[2,1]

[3,1]

RP

[1,2]

[3,2]

RP

[1,3]

[2,3]

wavelength router

P. Raatikainen

Switching Technology / 2003

12 - 16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optix-core-good-140111131404-phpapp02/75/Optical-Switching-Comprehensive-Article-313-2048.jpg)