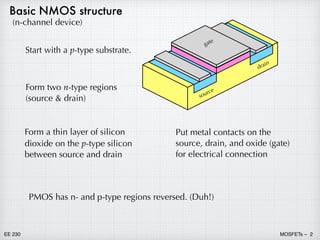

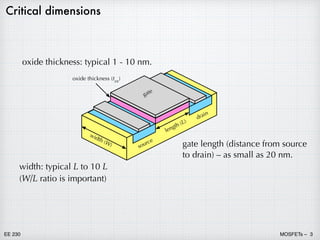

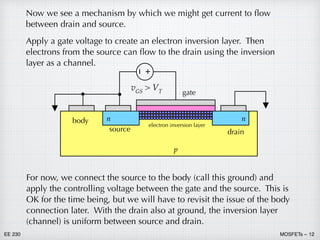

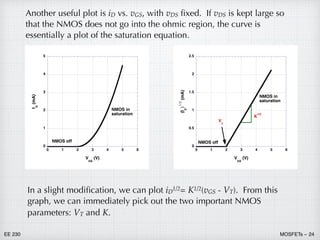

1) Metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors (MOSFETs) have replaced bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) for most digital and some analog applications. MOSFETs use a metal oxide semiconductor structure to control current flow through an inversion layer between the source and drain using a gate voltage.

2) A p-channel MOSFET (PMOS) uses holes for current flow, while an n-channel MOSFET (NMOS) uses electrons. Combining NMOS and PMOS in complementary MOS (CMOS) circuits provides significant advantages in design.

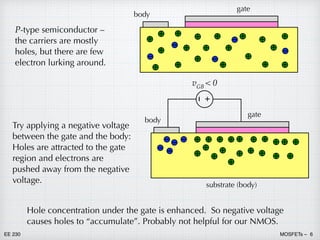

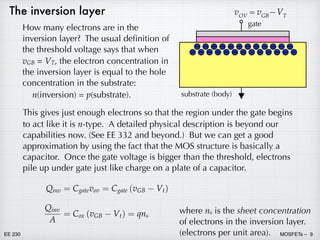

3) Applying different gate voltages results in either hole or electron accumulation at the semiconductor surface, depletion of carriers, or formation of an

![EE 230 MOSFETs – 22

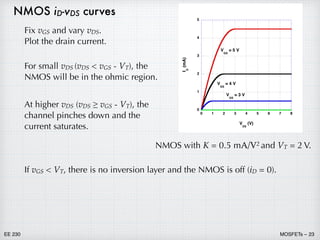

The mathematical analysis of what happens in a FET at pinch-off is a

fairly complicated problem in electromagnetics – definitely beyond

our current capabilities. (Again, see EE 332.)

However, the end result on the device behavior is easy to grasp – the

current saturates at the pinch down value. For higher values of vDS, the

current stays constant at a constant value.

The condition for the NMOS going reaching the “pinch-down”

condition is vGD ≤ VT. This can be re-expressed in terms of vDS and vGS.

To determine the saturation current, we can insert the pinch-down

condition given above into the iD-vDS equation from the ohmic region

of operation. Then the saturated current is

Y'6 Y*6 97

L' (VDW) =

ܟQR[

:

/

[Y*6 97]

= . [Y*6 97]

(Work out these details for yourself.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nmos1-240206014513-1d6a6e1f/85/nmos-pdf-22-320.jpg)

![EE 230 MOSFETs – 25

iD = 0

Summary of NMOS equations

The equations are exact (within the limits of the simplest MOSFET

model). The quadratic dependence of current on voltage means that

the circuit analysis will be non-linear and we will have frequent need

for the quadratic equation.

off

vGS VT

vGS ≥ VT on vDS vGS – VT ohmic or linear

vDS ≥ vGS – VT saturation

L' =

ܟQR[

:

/

(Y*6 97) Y'6 Y

'6

. =

ܟQR[

:

/

VT,

L' = . [Y*6 97]

iG = 0 !! (at least at DC)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nmos1-240206014513-1d6a6e1f/85/nmos-pdf-25-320.jpg)