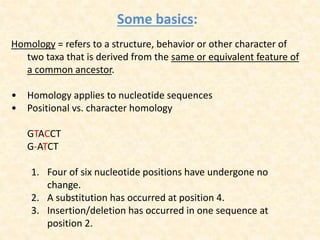

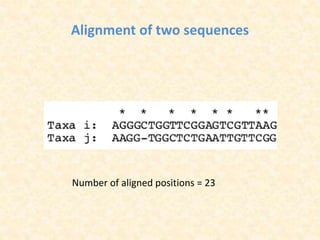

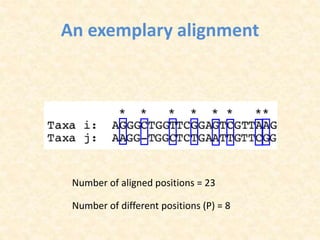

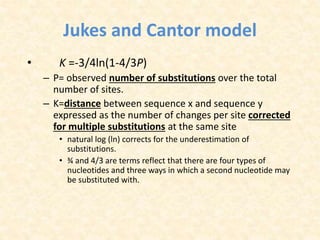

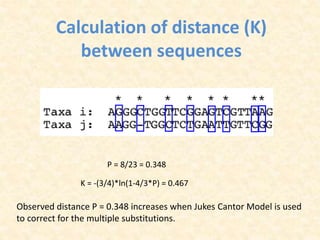

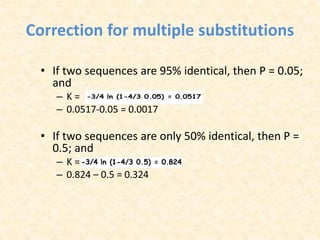

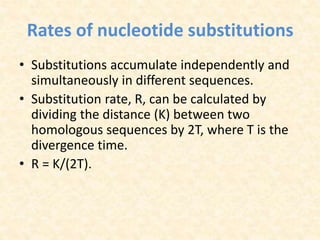

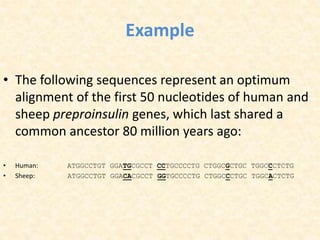

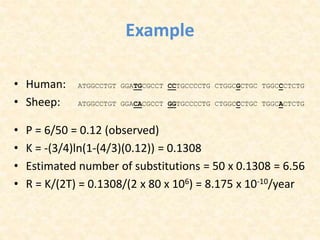

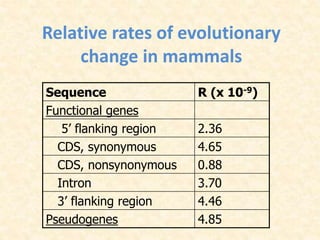

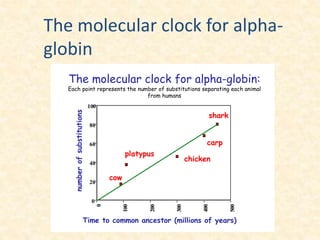

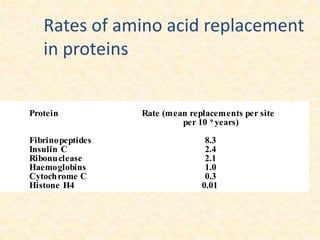

This document provides an overview of molecular evolution. It defines molecular evolution as the process of change in DNA, RNA, and protein sequences across generations, as examined using principles of evolutionary biology and population genetics. The history and key developments in the field are discussed, including the neutral theory of molecular evolution. Applications like revealing evolutionary dynamics, indicating chronological change, and identifying phylogenetic relationships are covered. Details are provided about sequence alignments, substitutions, molecular clocks, and variation in evolutionary rates within genes.