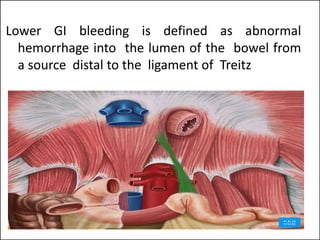

This document discusses lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, including:

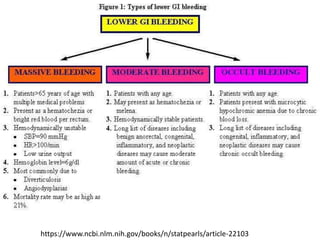

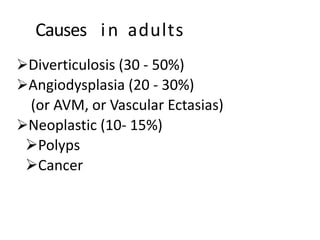

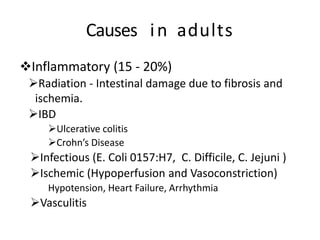

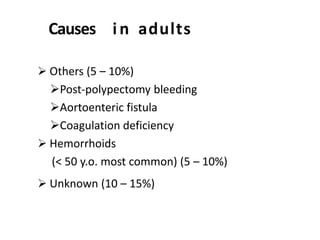

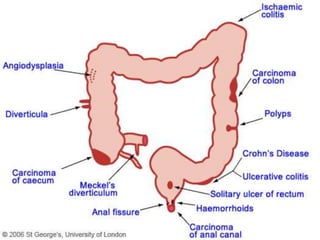

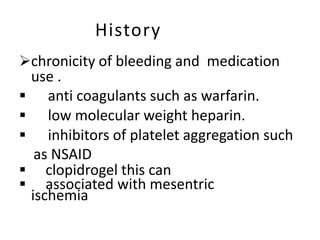

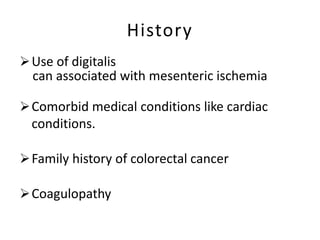

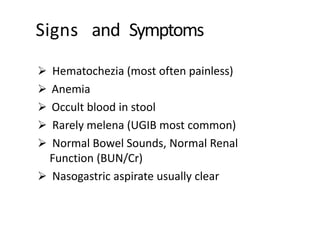

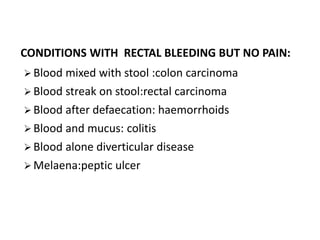

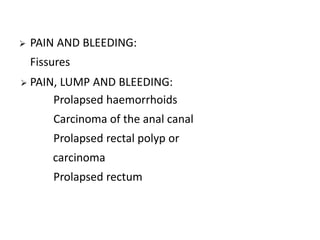

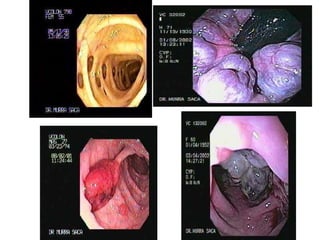

- Causes of lower GI bleeding in adults include diverticulosis, angiodysplasia, and colorectal cancers and polyps. Risk factors include low fiber diet and medications like NSAIDs.

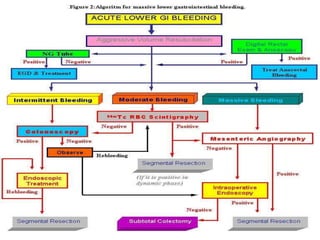

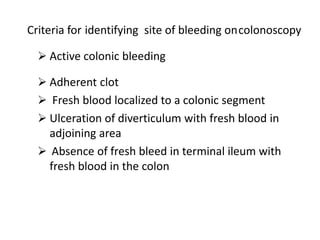

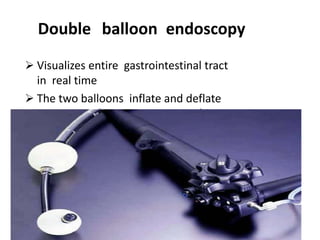

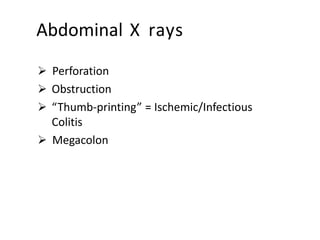

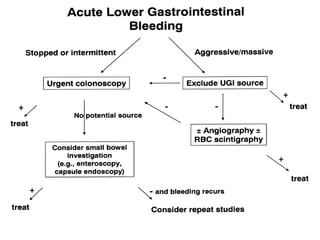

- Evaluation involves history, physical exam, labs, and endoscopic procedures like colonoscopy to identify the bleeding source and provide treatment.

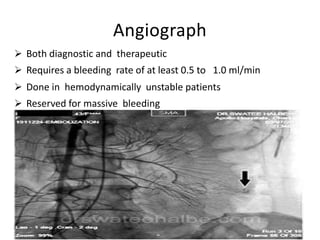

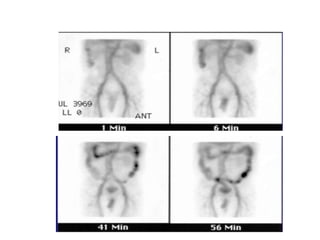

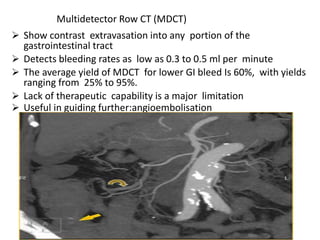

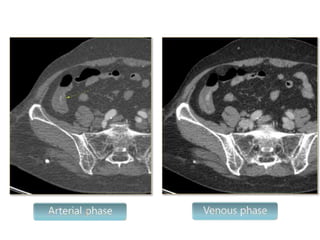

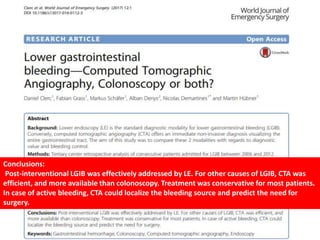

- Colonoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment but must be performed carefully in unstable patients. Angiography and nuclear scans can help localize bleeding in severe cases.

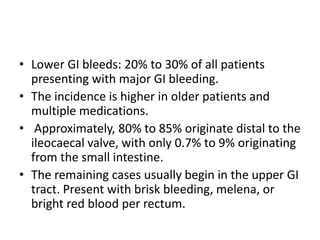

![Epidemiology

Overall mortality <5%.

[Frequency and severity of UGIB >LGIB]

LGIB is more common in women > men.

Incidence and prevalence related to specific etiologies

More than 80% of lower GI bleeds will stop

spontaneously, and overall mortality has been noted to

be 2% to 4%.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lowergibleed-201013054845/85/Lower-Gastrointestinal-Bleed-3-320.jpg)