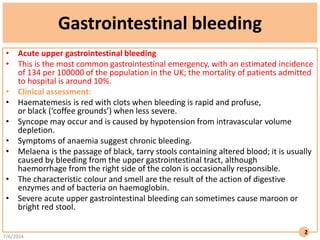

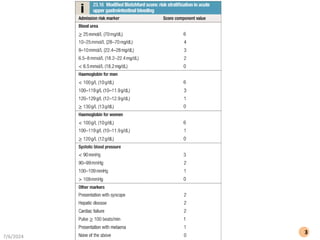

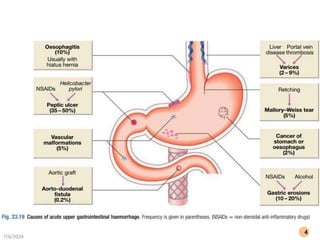

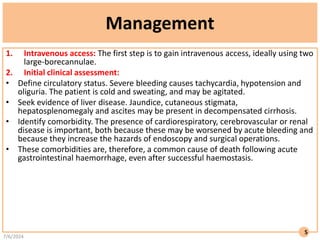

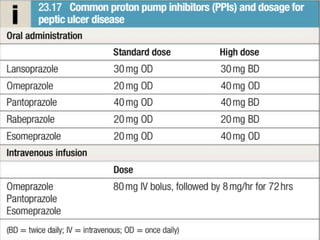

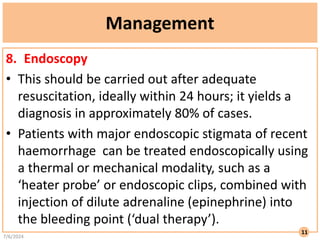

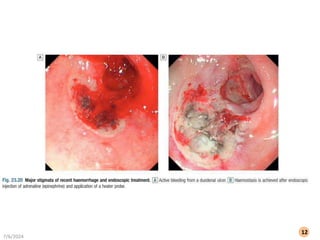

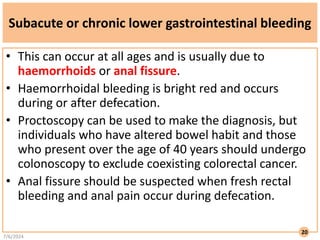

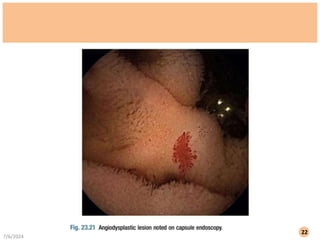

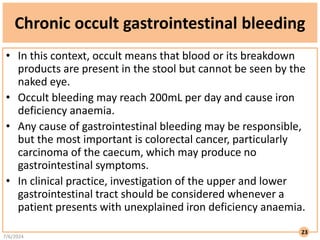

The document discusses gastrointestinal bleeding, focusing on its prevalence, symptoms, clinical assessment, and management strategies for both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeds. It outlines various diagnostic methods, treatment options such as endoscopy, angiography, and surgery, and emphasizes monitoring and management of co-morbidities. Specific recommendations include intravenous fluid resuscitation, transfusion protocols, and use of proton pump inhibitors, while also addressing lower gastrointestinal sources and chronic occult bleeding.