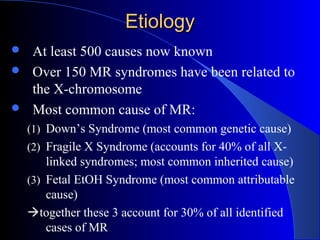

This document provides information on intellectual disability (ID), including definitions, levels of severity, comorbid disorders, risk factors, causes, and treatment with psychotropic medications. Key points include:

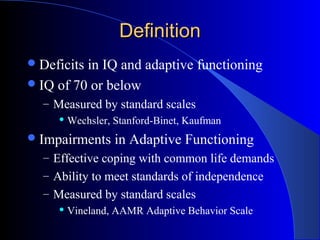

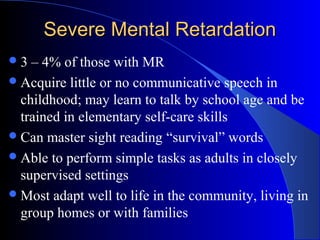

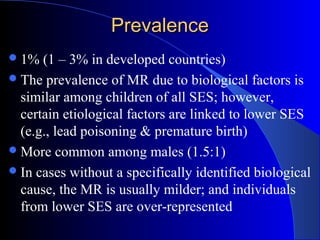

- ID is defined by deficits in both IQ (70 or below) and adaptive functioning. It ranges from mild to profound depending on IQ scores.

- The most common causes are Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome, together accounting for 30% of cases.

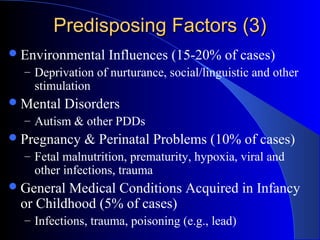

- Risk factors include heredity, early embryonic alterations, environmental influences, and pregnancy/birth complications.

- Common comorbid disorders are ADHD, mood disorders, and autism spectrum disorders. Stimulants and

![Fetal EtOH SyndromeFetal EtOH Syndrome

Incidence > 1:1000

Irritable as infants, hyperactive as children (ADHD)

Teratogen amount: 2 drinks/day (smaller birth size), 4-6

drinks/day (subtle clinical features), 8-10 drinks/day (full

syndrome)

General problems: prenatal onset of growth deficiency,

microcephaly, short palpebral fissures

Syndrome can include:

– Facial deformities (ptosis of eyelid, microphthalmia, cleft lip [+/- palate],

micrognathia, flattened nasal bridge and filtrum, & protruding ears)

– CNS deformities (meningomyelocele, hydrocephalus)

– Neck deformities (mild webbing, cervical vertebral & rib abmormalities)

– Cardiac deformities (tetralogy of Fallot, coarctation of aorta)

– Other abnormalities (hypoplastic labia majora, strawberry hemangiomata)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intellectualdisability-150415051941-conversion-gate01/85/Intellectual-disability-25-320.jpg)