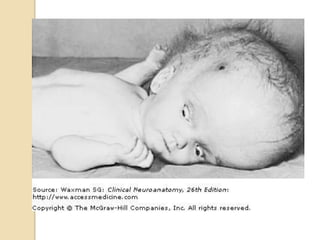

Hydrocephalus, commonly known as "water on the brain", is an abnormal buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain's ventricles. Congenital/infantile hydrocephalus develops before age 3 and causes the skull to enlarge rapidly. Common causes include brain hemorrhages, infections, or malformations. Symptoms include a tense, enlarged head and developmental delays. As pressure increases, vision loss, seizures, and cognitive impairments occur. Untreated, hydrocephalus can be fatal due to brain herniation through openings in the skull.

![ even of mild degree, it molds the

shape of the skull in early life

in radiographs the inner table is

unevenly thinned, an appearance

referred to as "beaten silver" or as

convolutional or digital markings.

The frontal regions are unusually

prominent [bossing]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydrocephalus-120416141248-phpapp02/85/Hydrocephalus-by-DR-ARSHAD-10-320.jpg)

![ an increase in volume of any one of

these three components must be at

the expense of the other two [Monro-

Kellie doctrine]

Compensatory measures

Small increments in brain volume do

not immediately raise the ICP due to

displacement of CSF from the cranial

cavity into the spinal canal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydrocephalus-120416141248-phpapp02/85/Hydrocephalus-by-DR-ARSHAD-23-320.jpg)