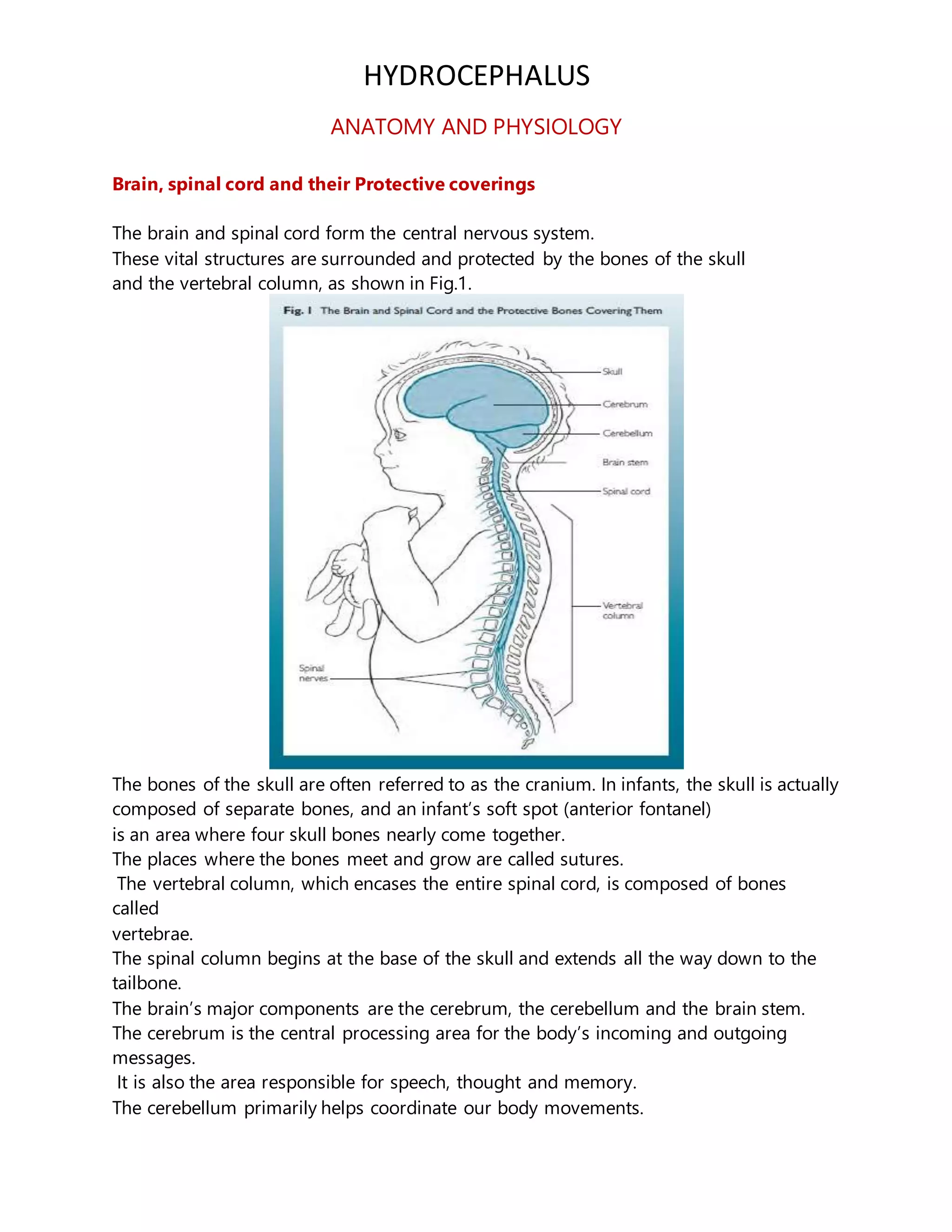

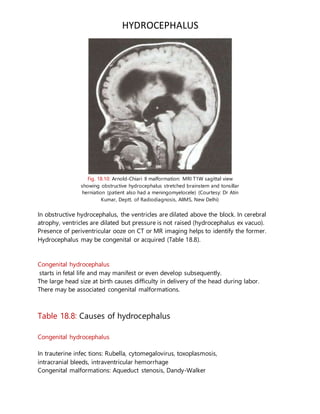

The document discusses hydrocephalus, beginning with the anatomy and physiology of the brain, spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It defines hydrocephalus as an abnormal accumulation of CSF within brain ventricles. Hydrocephalus results from an imbalance between CSF production and absorption and can be communicating or noncommunicating. The clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of hydrocephalus are described.