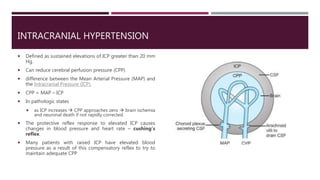

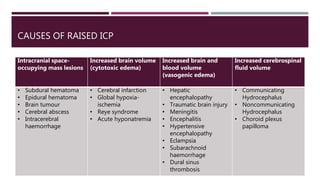

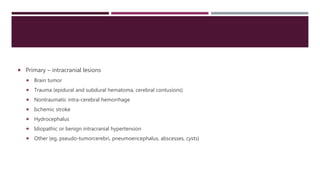

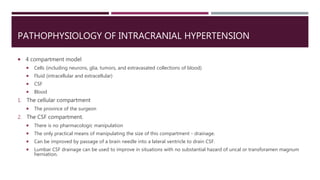

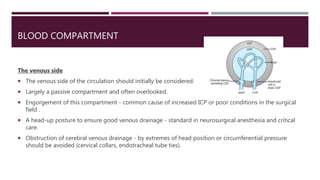

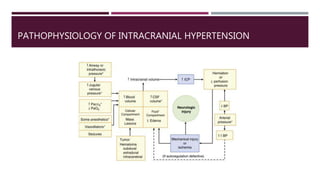

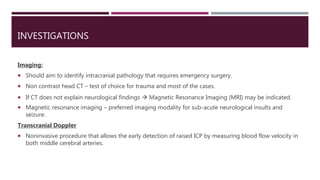

This document discusses intracranial pressure (ICP), including its normal values, causes of elevated ICP, clinical signs and symptoms, investigation methods, and monitoring techniques. ICP is the pressure within the skull, which contains brain tissue, blood vessels, and cerebrospinal fluid. Elevated ICP above 20 mmHg is considered intracranial hypertension and can reduce blood flow to the brain. Causes include brain tumors, hemorrhages, edema, and hydrocephalus. Signs may include headache, nausea, blurred vision, and altered mental status. Imaging like CT and MRI can identify underlying pathology. Monitoring ICP directly via an intraparenchymal probe is important for managing critically elevated pressures.

![IV AGENTS

Thiopentone

protect brain from incomplete ischemia.

suppresses CMR.

Helps in free radical scavenging effects and decrease ATP consumption.

Cerebral autoregulation maintained and CO2 responsiveness intact.

Methohexital:

It has myoclonic activity and patients with seizures of temporal lobe origin [psychomotor variety] are specifically

at risk](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intracranialpressure-200611141423/85/Intracranial-pressure-75-320.jpg)

![NITROUS OXIDE

Can cause significant increase in CBF, CMR & ICP by its sympatho-adrenal stimulating effect.

This effect is most extensive when used alone.

Nitrous with IV agents: CBF effect considerably reduced [thiopentone, propofol, benzodiazepines,

narcotics].

Nitrous with volatile agents: CBF increase is exaggerated.

Vasodilator effect clinically significant in those with abnormal intracranial compliance.

It should be avoided in cases, where a closed intracranial gas space may exist, since it can its cause

expansion.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intracranialpressure-200611141423/85/Intracranial-pressure-82-320.jpg)