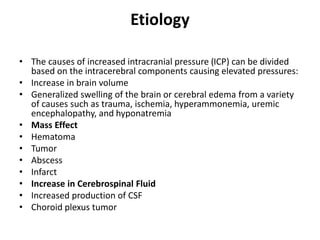

The document discusses intracranial hypertension (increased intracranial pressure). It defines intracranial pressure as the pressure within the cranial vault, which contains brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood. Any increase in the volume of these components will increase intracranial pressure due to the rigid skull. The document outlines the causes, signs/symptoms, evaluation, and treatment of increased intracranial pressure, including lowering intracranial pressure through measures such as head elevation, hyperventilation, and administration of osmotic agents/steroids. Care coordination among healthcare professionals is important for optimizing treatment and outcomes for patients with this condition.

![• The cranium is a rigid structure that contains three

main components: brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and

blood. Any increase in the volume of its contents will

increase the pressure within the cranial vault. The

Monroe-Kellie Doctrine states that the contents of the

cranium are in a state of constant volume.[1] That is,

the total volumes of the brain tissues, cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF), and intracranial blood are fixed. An increase

in the volume of one component will result in a

decrease in volume in one or two of the other

components. The clinical implication of the change in

volume of the component is a decrease in cerebral

blood flow or herniation of the brain.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-5-320.jpg)

![Epidemiology

• The true incidence of intracranial hypertension is

unknown. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) estimates that in 2010, 2.5

million people sustained a traumatic brain injury

(TBI). TBI is associated with increased ICP. ICP

monitoring is recommended for all patients with

severe TBI. Studies of American-based

populations have estimated that the incidence of

idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) ranges

from 0.9 to 1.0 per 100,000 in the general

population, increasing in women that are

overweight.[2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-9-320.jpg)

![Pathophysiology

• The harmful effects of intracranial hypertension are primarily due to

brain injury caused by cerebral ischemia. Cerebral ischemia is the

result of decreased brain perfusion secondary to increased ICP.

Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is the pressure gradient between

mean arterial pressure (MAP) and intracranial pressure (CPP = MAP

- ICP).[3] CPP = MAP - CVP if central venous pressure is higher than

intracranial pressure. CPP target for adults following severe

traumatic brain injury is recommended at greater than 60 to 70 mm

Hg, and a minimum CPP greater than 40 mm Hg is recommended

for infants, with very limited data on normal CPP targets for

children in between.

• Cerebral autoregulation is the process by which cerebral blood flow

varies to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion. When the MAP is

elevated, vasoconstriction occurs to limit blood flow and maintain

cerebral perfusion. However, if a patient is hypotensive, cerebral

vasculature can dilate to increase blood flow and maintain CPP.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-10-320.jpg)

![History and Physical

• Clinical suspicion for intracranial hypertension should be raised if a

patient presents with the following signs and symptoms:

headaches, vomiting, and altered mental status varying from

drowsiness to coma. Visual changes can range from blurred vision,

double vision from cranial nerve defects, photophobia to optic disc

edema, and eventually optic atrophy. Infants in whom the anterior

fontanelle is still open may have a bulge overlying the area.

• Cushing triad is a clinical syndrome consisting of hypertension,

bradycardia, and irregular respiration and is a sign of impending

brain herniation. This occurs when the ICP is too high the elevation

of blood pressure is a reflex mechanism to maintain CPP. High blood

pressure causes reflex bradycardia and brain stem compromise

affecting respiration. Ultimately the contents of the cranium are

displaced downwards due to the high ICP, causing a phenomenon

known as herniation which can be potentially fatal.[4]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-11-320.jpg)

![Evaluation

• The evaluation of increased ICP should include detailed history taking, physical examination, and

ancillary studies.

• It is extremely important to identify increased ICP as early as possible to prevent herniation and

death. For example malignant middle cerebral artery stroke presenting with increased ICP.

Malignant middle cerebral artery stroke is seen more commonly in the younger population. Usually,

these patients are admitted to the ICU setting. Following the neurological exam closely is very

important. Usually, there is an altered mental status and development of a fixed and dilated

pupil. Patients presenting with findings suggestive of cerebral insult should undergo computed

tomography (CT) scan of the brain; this can show the edema, which is visible as areas of low density

and loss of gray/white matter differentiation, on an unenhanced image. There can also be an

obliteration of the cisterns and sulcal spaces. A CT scan can also reveal the cause in some cases. If

flattened gyri or narrowed sulci, or compression of the ventricles, is seen, this suggests increased

ICP. Serial CT scans are used to monitor the progression or improvement of the edema.[5]

• A funduscopic exam can reveal papilledema which is a tell-tale sign of raised ICP as the

cerebrospinal fluid is in continuity with the fluid around the optic nerve.

• Imaging- a computed tomography (CT) of the head or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can reveal

signs of raised ICP such as enlarged ventricles, herniation, or mass effect from causes such as

tumors, abscesses, and hematomas, among others.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-12-320.jpg)

![• Measurement of Opening Pressure with a Lumbar Puncture

• In this procedure, a needle is introduced in the subarachnoid space. This can be

connected to a manometer to give the pressure of the CSF prior to drainage. A

measurement greater than 20 mm Hg is suggestive of raised ICP. Brain imaging

should precede an LP because LP can cause a sudden and rapid decrease in ICP

and the sudden change in volume can lead to herniation.

• ICP Monitoring [6]

• Several devices can be used for ICP monitoring.

• The procedure involves the placement of a fiber optic catheter into the brain

parenchyma to measure the pressure transmitted to the brain tissue.

• External Ventricular Drain (EVD)

• A drain placed directly into the lateral ventricles can be connected to a manometer

to give a reading for the pressure in the ventricles.

• Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter (ONSD) [7]

• The use of ultrasound to measure the diameter of the optic nerve sheath has been

recently identified as a method to indicate raised ICP. This is usually measured 3

mm behind the globe with 2–3 measurements taken in each eye. The threshold for

denoting elevated ICP usually ranges from 0.48 cm to 0.63 cm.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-13-320.jpg)

![Treatment / Management

• Assessment and management of the airway, specifically breathing and circulation should always be

the priority.[8]

• Management principles should be targeted toward:

• Maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure by raising MAP

• Treatment of the underlying cause.

• Lowering of ICP.[9]

• Measures to lower ICP include:[10]

• Elevation of the head of the bed to greater than 30 degrees.

• Keep the neck midline to facilitate venous drainage from the head.

• Hypercarbia lowers serum pH and can increase cerebral blood flow contributing to rising ICP, hence

hyperventilation to lower pCO2 to around 30 mm Hg can be transiently used.

• Osmotic agents can be used to create an osmotic gradient across blood thereby drawing fluid

intravascularly and decreasing cerebral edema. Mannitol was the primary agent used at doses of

0.25 to 1 g/kg body weight and is thought to exert its greatest benefit by decreasing blood viscosity

and to a lesser extent by decreasing blood volume. Side effects of mannitol use are eventual

osmotic diuresis and dehydration as well as renal injury if serum osmolality exceeds 320

mOsm.[11] Steroids are indicated to reduce ICP in intracranial neoplastic tumors, but not in

traumatic brain injury.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-14-320.jpg)

![• Three percent hypertonic saline is also commonly used to decrease

cerebral edema and can be administered as a 5 ml/kg bolus or a

continuous infusion, monitoring serum sodium levels closely. It is

considered relatively safe while serum sodium is < than 160mEq/dl

or serum osmolality is less than 340 mOsm.[12]

• Drugs of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor class, such as

acetazolamide, can be used to decrease the production of CSF and

is used to treat idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

• Lumbar punctures, besides being diagnostic, can be used to drain

CSF thus reducing the ICP. The limitation to this is raised ICP

secondary to mass effect with a possible risk of herniation if the CSF

pressure drops too low.

• Similar to a lumbar puncture, an EVD can also be used to not only

monitor ICP but also to drain CSF.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-15-320.jpg)

![• Optic nerve fenestrations can be performed for patients with chronic

idiopathic hypertension at a risk of blindness. Neurosurgical shunts such

as ventriculoperitoneal or lumbar-peritoneal shunts can divert CSF to

another part of the body from where it can be reabsorbed.[13]

• Intravenous (IV) glyburide is being investigated in the prevention of

hemispheric stroke edema. It acts by inhibiting SUR1 receptors.[14]

• Barbiturates can be considered in cases where sedation and usual

methods of treatment are not successful in reducing the ICP.[15]

• Therapeutic hypothermia to 32-35 degrees Celcius can be used in a

refractory rise in ICP not responding to hyperosmolar therapy and

barbiturate coma. But its use has been questioned in recent days.

• A decompressive craniectomy is a neurosurgical procedure wherein a part

of the skull is removed, and dura lifted, allowing the brain to swell without

causing compression.[16] It is usually considered as a last resort when all

other ICP lowering measures have failed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-16-320.jpg)

![• Mokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology. 2001 Jun 26;56(12):1746-8. [PubMed]

• 2.Kilgore KP, Lee MS, Leavitt JA, Mokri B, Hodge DO, Frank RD, Chen JJ. Re-evaluating the Incidence of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension in an Era

of Increasing Obesity. Ophthalmology. 2017 May;124(5):697-700. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• 3.Mount CA, M Das J. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Apr 5, 2022. Cerebral Perfusion Pressure. [PubMed]

• 4.Munakomi S, M Das J. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 9, 2022. Brain Herniation. [PubMed]

• 5.Nehring SM, Tadi P, Tenny S. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 31, 2022. Cerebral Edema. [PubMed]

• 6.Munakomi S, M Das J. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 9, 2022. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring. [PubMed]

• 7.Changa AR, Czeisler BM, Lord AS. Management of Elevated Intracranial Pressure: a Review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019 Nov

26;19(12):99. [PubMed]

• 8.Mtaweh H, Bell MJ. Management of pediatric traumatic brain injury. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2015 May;17(5):348. [PubMed]

• 9.Marehbian J, Muehlschlegel S, Edlow BL, Hinson HE, Hwang DY. Medical Management of the Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Patient. Neurocrit

Care. 2017 Dec;27(3):430-446. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• 10.Geeraerts T, Velly L, Abdennour L, Asehnoune K, Audibert G, Bouzat P, Bruder N, Carrillon R, Cottenceau V, Cotton F, Courtil-Teyssedre S, Dahyot-

Fizelier C, Dailler F, David JS, Engrand N, Fletcher D, Francony G, Gergelé L, Ichai C, Javouhey É, Leblanc PE, Lieutaud T, Meyer P, Mirek S, Orliaguet G,

Proust F, Quintard H, Ract C, Srairi M, Tazarourte K, Vigué B, Payen JF., French Society of Anaesthesia. Intensive Care Medicine. in partnership with

Association de neuro-anesthésie-réanimation de langue française (Anarlf). French Society of Emergency Medicine (Société Française de Médecine

d'urgence (SFMU). Société française de neurochirurgie (SFN). Groupe francophone de réanimation et d’urgences pédiatriques (GFRUP). Association

des anesthésistes-réanimateurs pédiatriques d’expression française (Adarpef). Management of severe traumatic brain injury (first 24hours). Anaesth

Crit Care Pain Med. 2018 Apr;37(2):171-186. [PubMed]

• 11.Knapp JM. Hyperosmolar therapy in the treatment of severe head injury in children: mannitol and hypertonic saline. AACN Clin Issues. 2005 Apr-

Jun;16(2):199-211. [PubMed]

• 12.Upadhyay P, Tripathi VN, Singh RP, Sachan D. Role of hypertonic saline and mannitol in the management of raised intracranial pressure in

children: A randomized comparative study. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2010 Jan;5(1):18-21. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• 13.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004 Jun;24(2):138-45. [PubMed]

• 14.Sheth KN, Elm JJ, Molyneaux BJ, Hinson H, Beslow LA, Sze GK, Ostwaldt AC, Del Zoppo GJ, Simard JM, Jacobson S, Kimberly WT. Safety and efficacy

of intravenous glyburide on brain swelling after large hemispheric infarction (GAMES-RP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2

trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016 Oct;15(11):1160-9. [PubMed]

• 15.Velle F, Lewén A, Howells T, Nilsson P, Enblad P. Temporal effects of barbiturate coma on intracranial pressure and compensatory reserve in

children with traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2021 Feb;163(2):489-498. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

• 16.Smith M. Refractory Intracranial Hypertension: The Role of Decompressive Craniectomy. Anesth Analg. 2017 Dec;125(6):1999-2008. [PubMed]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/increasedintracranialpressure-230503055647-befcbf9c/85/increased-intracranial-pressure-pptx-22-320.jpg)