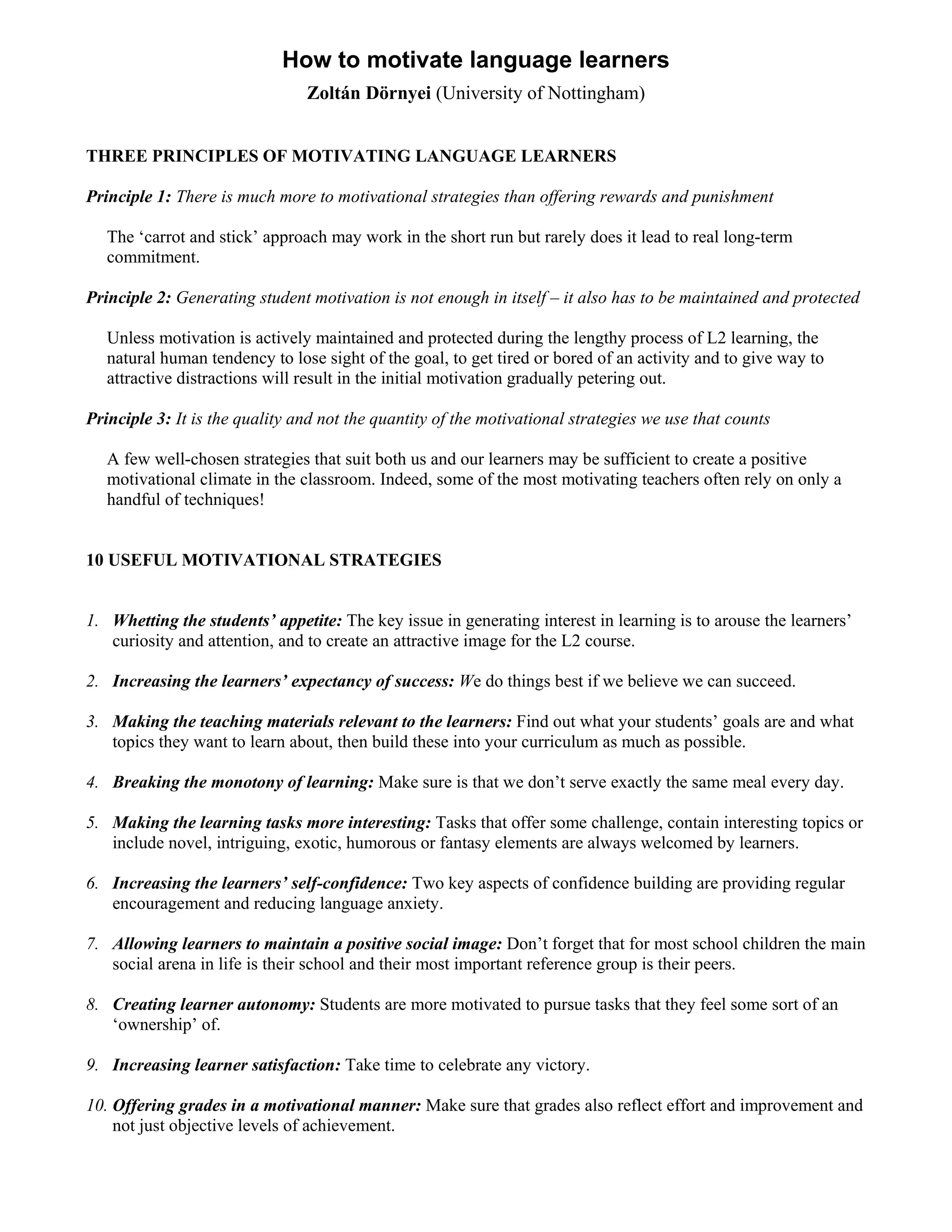

The document discusses three principles of motivating language learners: 1) rewards and punishment do not lead to long-term commitment, 2) motivation must be maintained over time to prevent losing interest, and 3) quality rather than quantity of motivational strategies is important. It also outlines 10 useful motivational strategies such as increasing relevance, interest, and confidence. Additionally, it proposes a visionary motivational program involving constructing an ideal language self, strengthening this vision, making it realistic, and keeping it alive to motivate long-term learning.