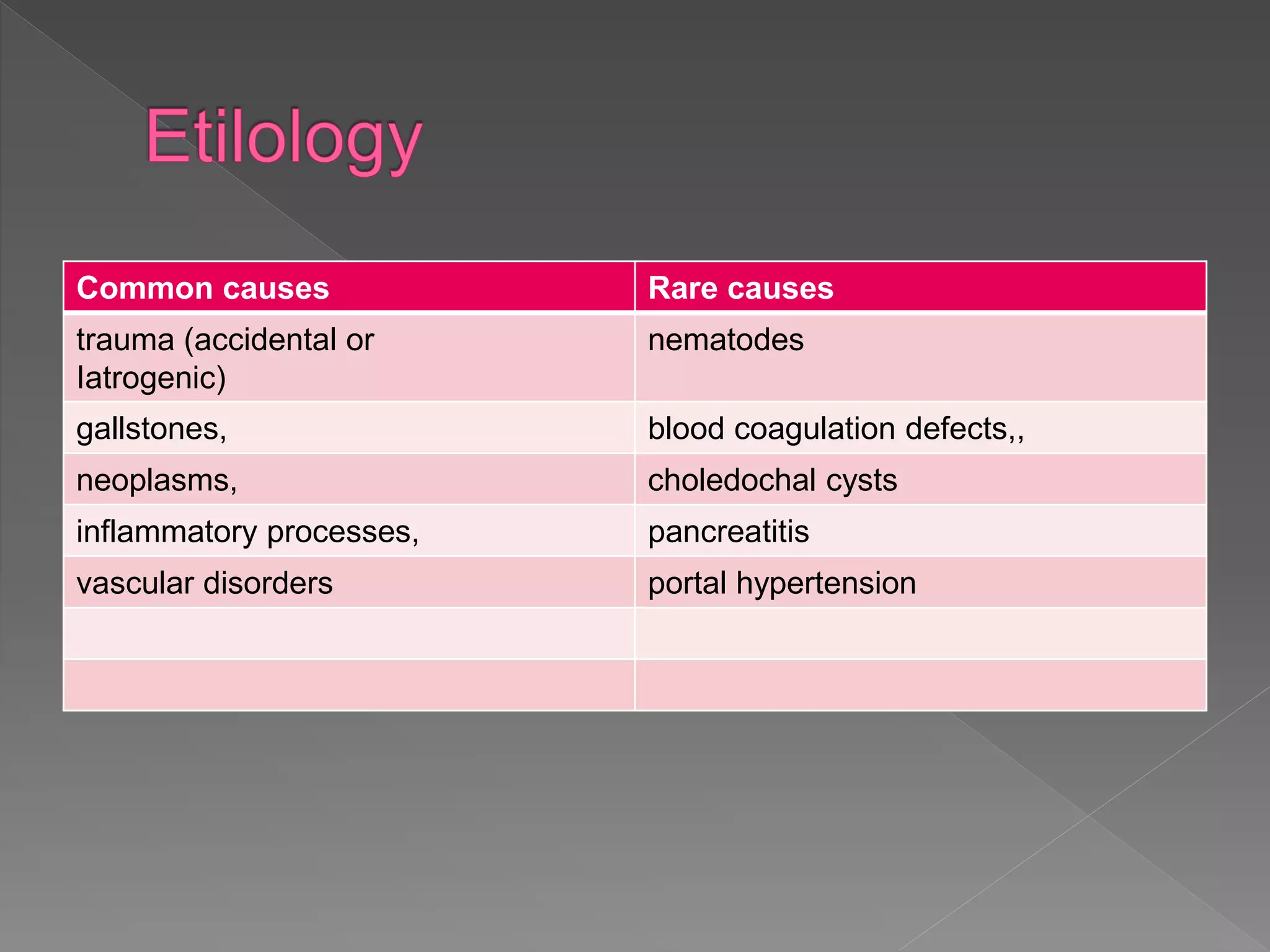

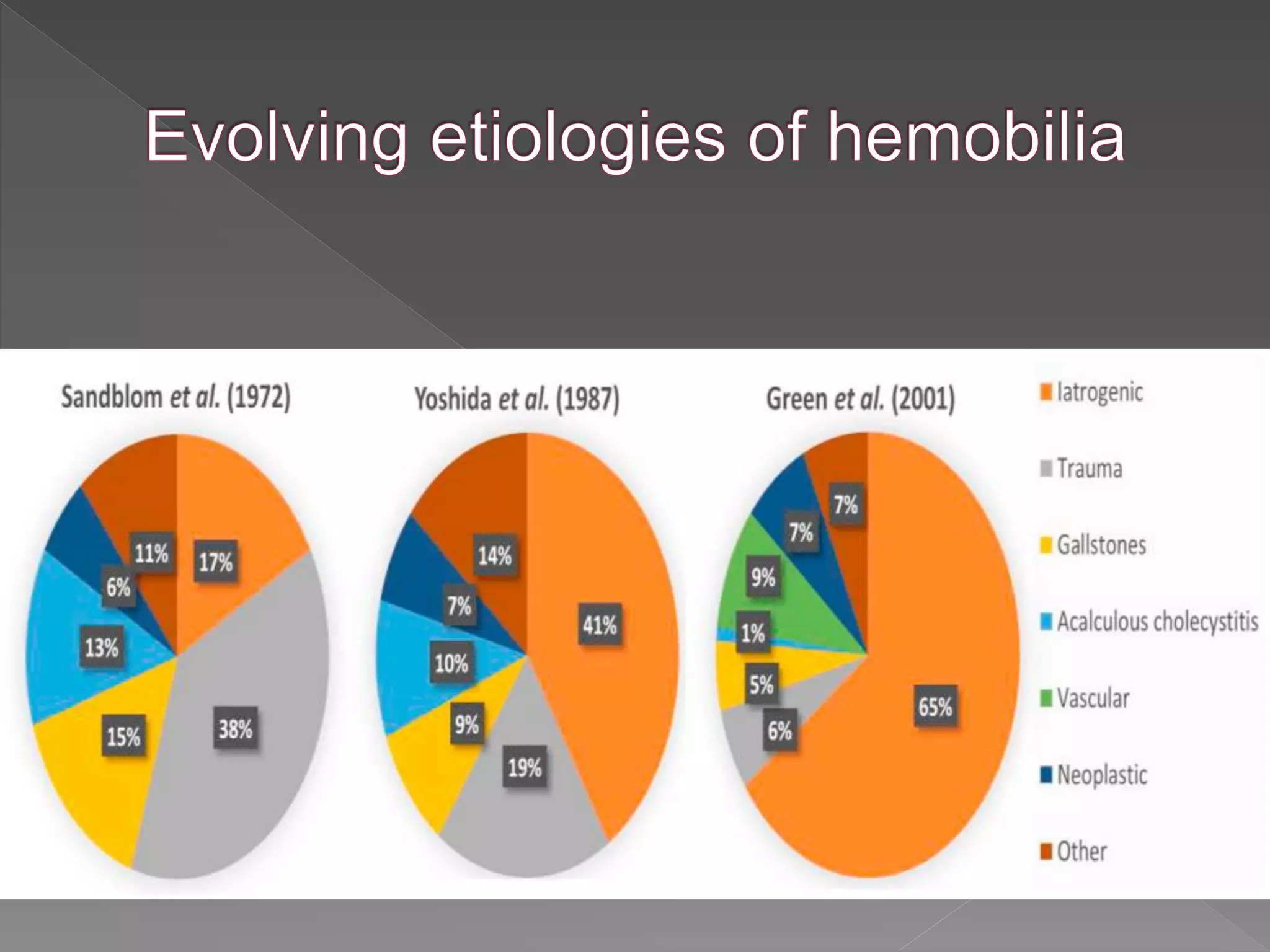

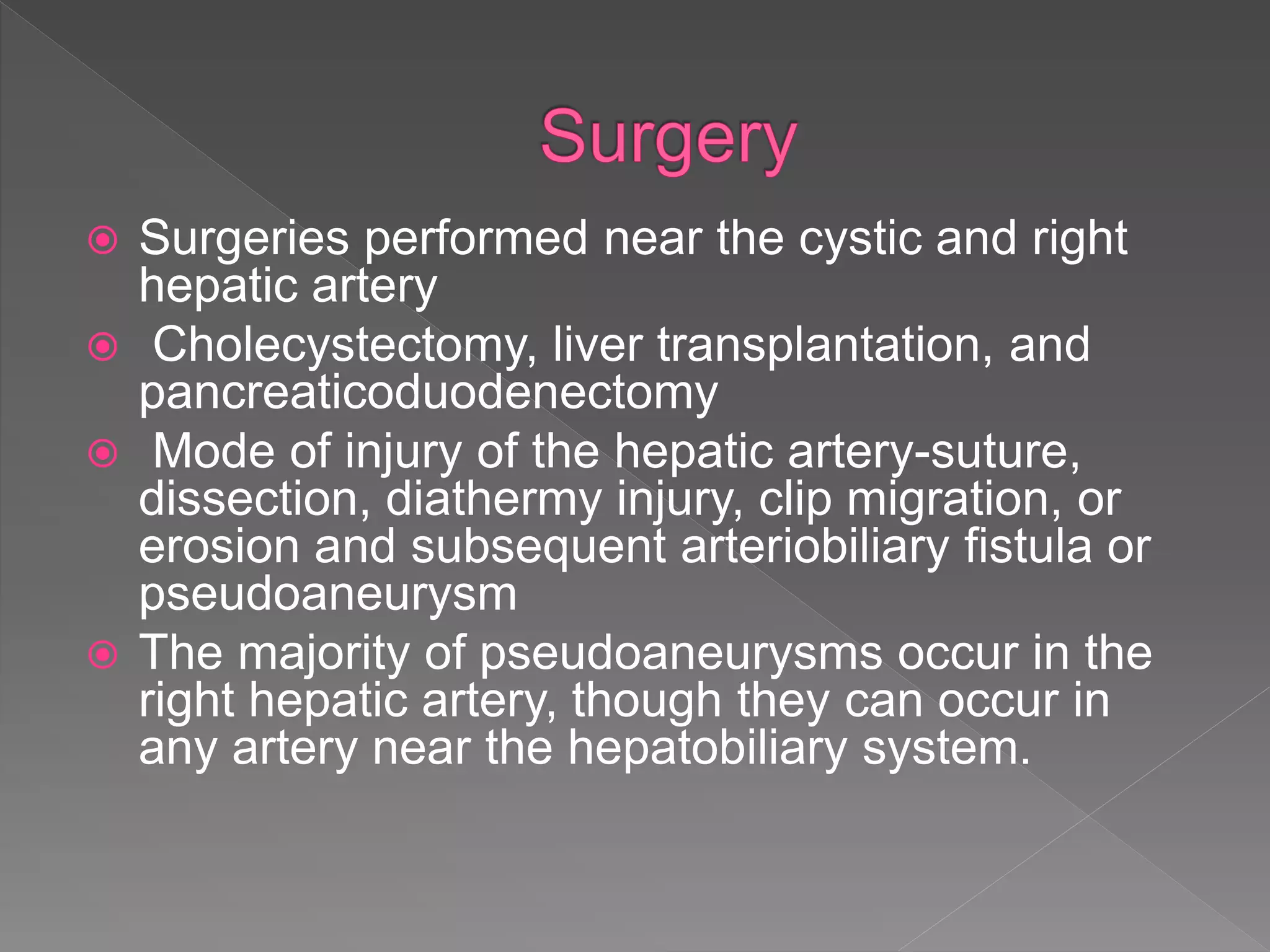

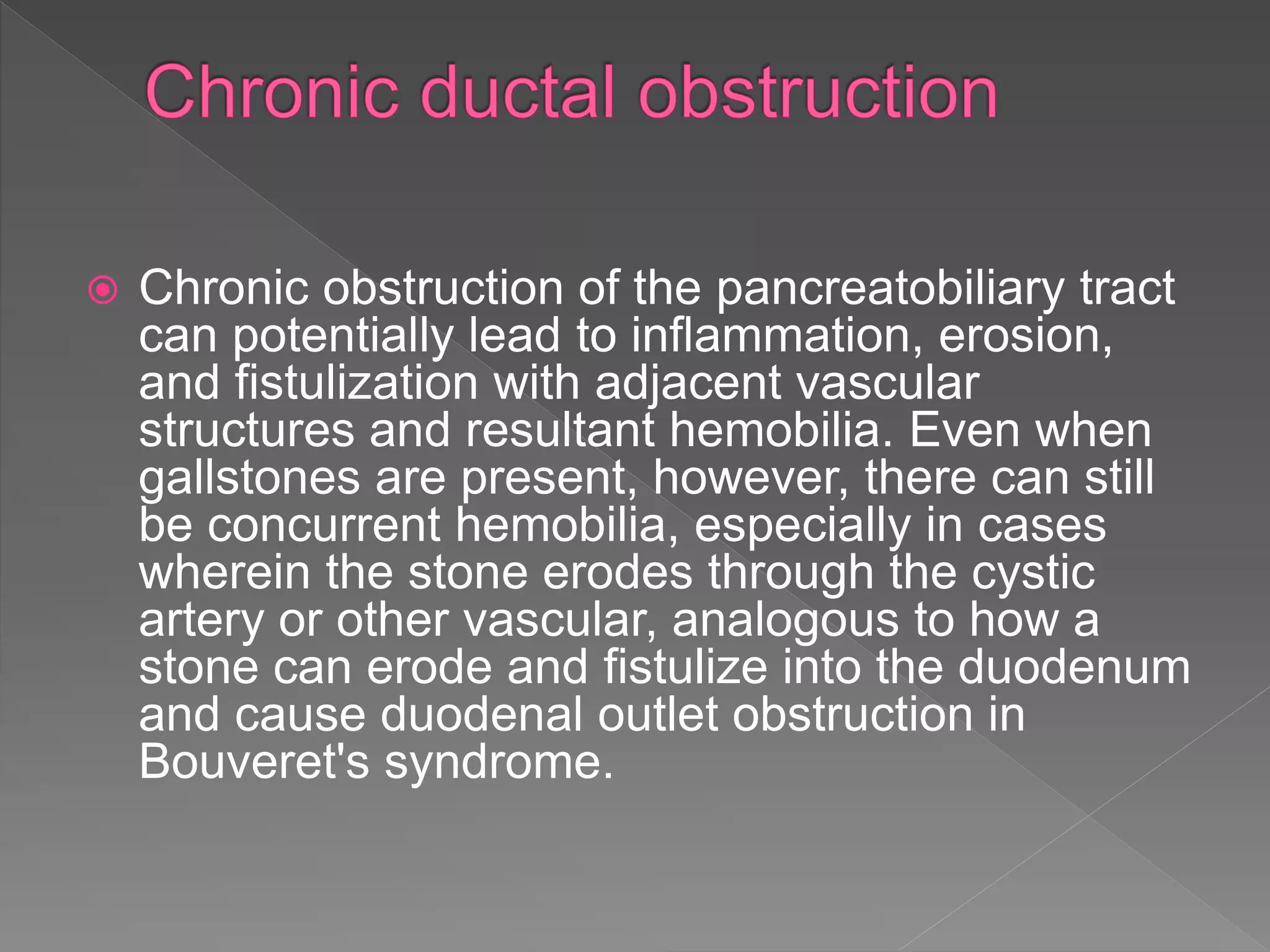

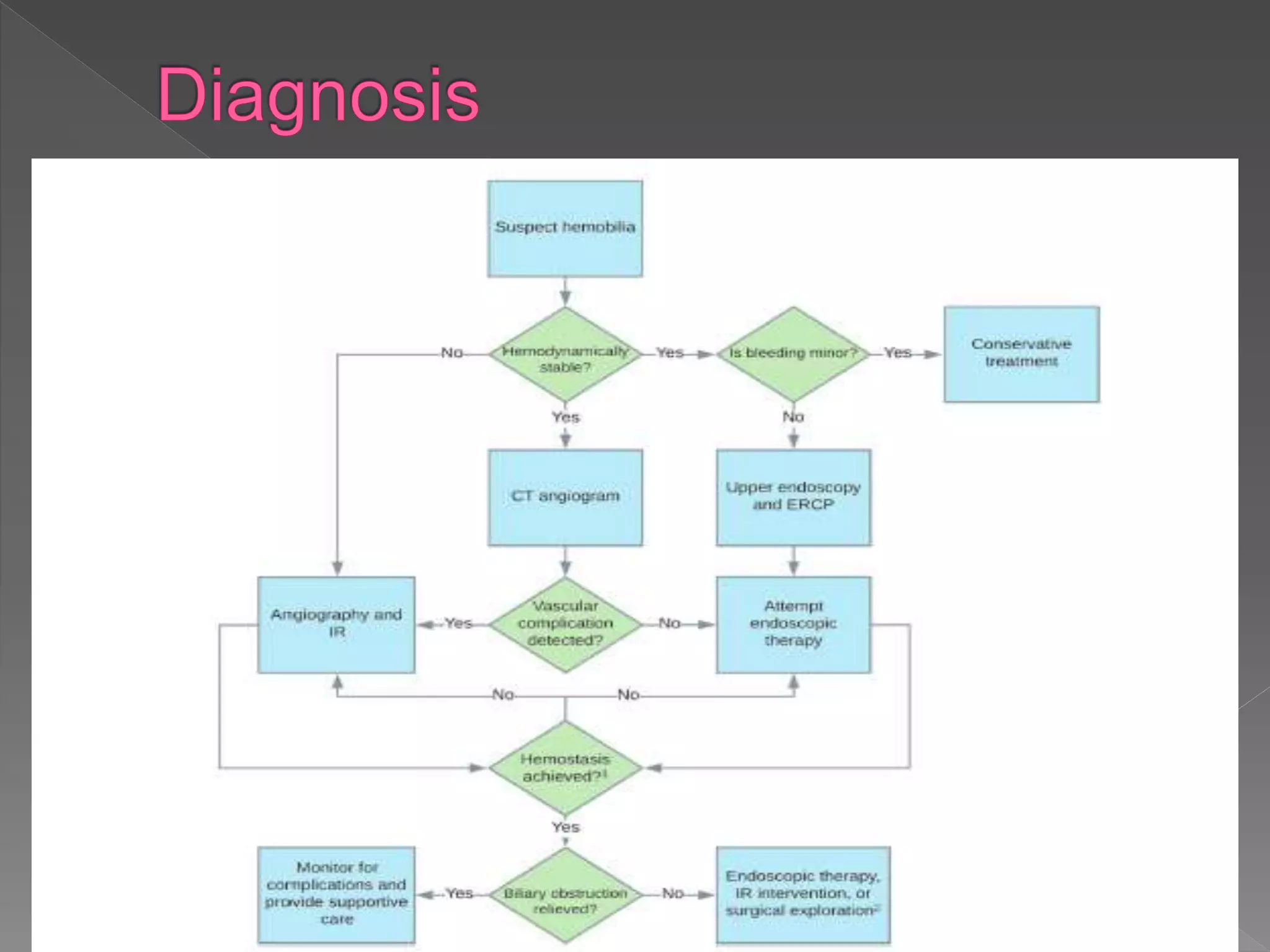

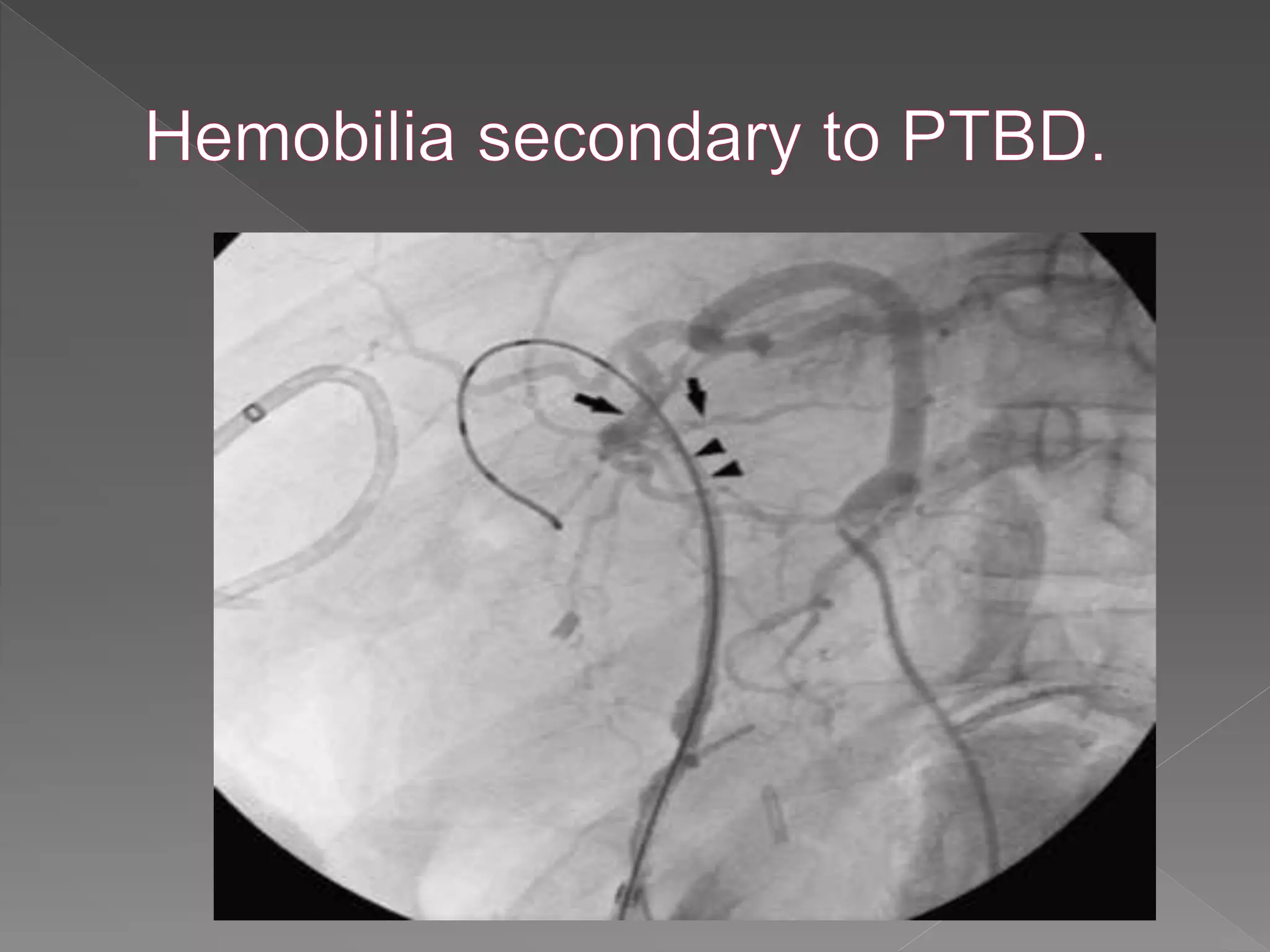

This document defines hemobilia and provides information on its history, causes, clinical presentation, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Hemobilia refers to bleeding into the biliary tract from abnormal connections between blood vessels and bile ducts. It can result from traumatic or iatrogenic injuries, gallstones, tumors, or vascular abnormalities. Clinical features include gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, and jaundice. Angiography and endoscopy are important diagnostic tools. Treatment depends on the bleeding source but may involve endoscopic methods, transarterial embolization, covered stents, or surgery. The goal is to achieve hemostasis while maintaining bile flow.