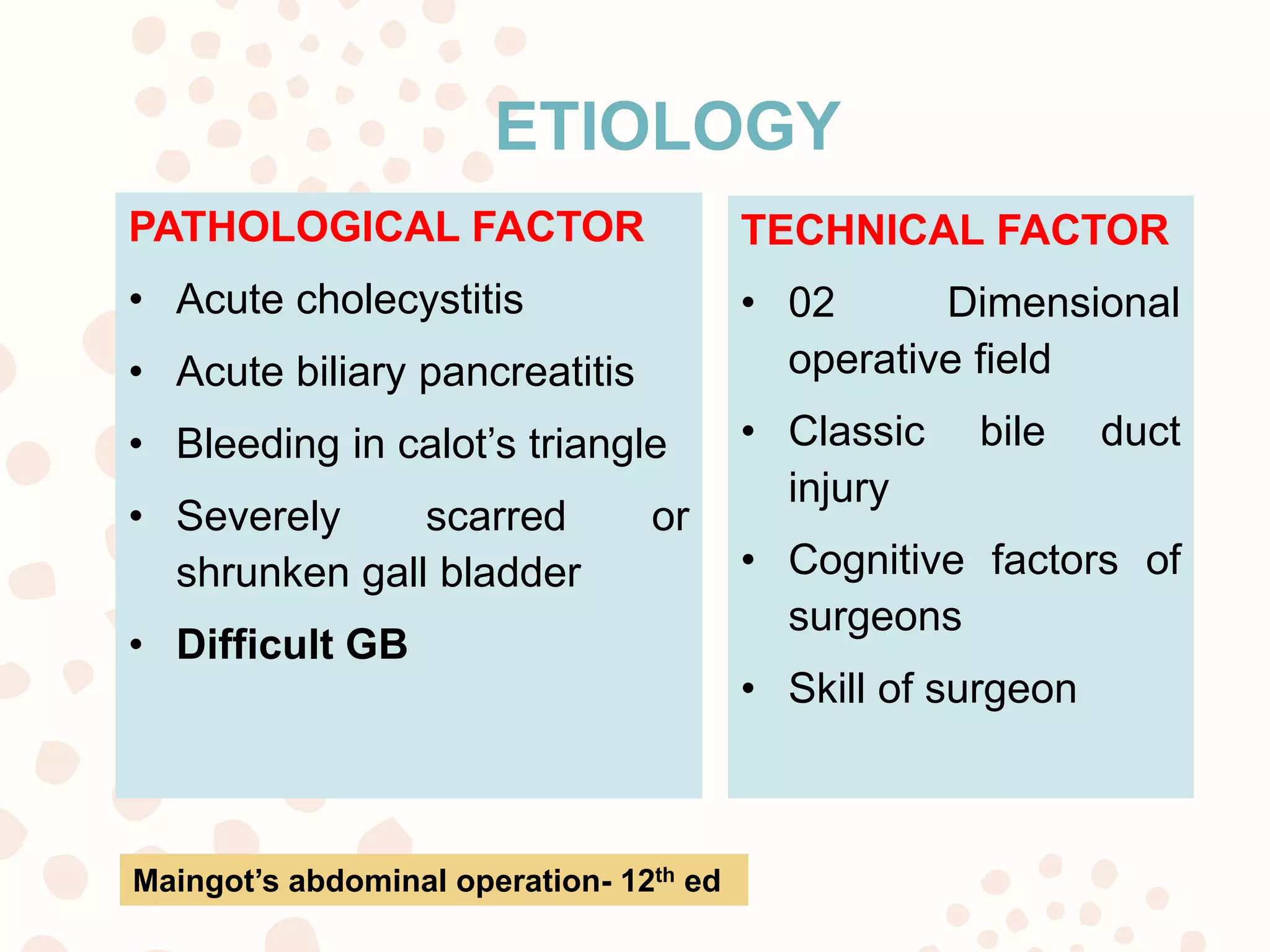

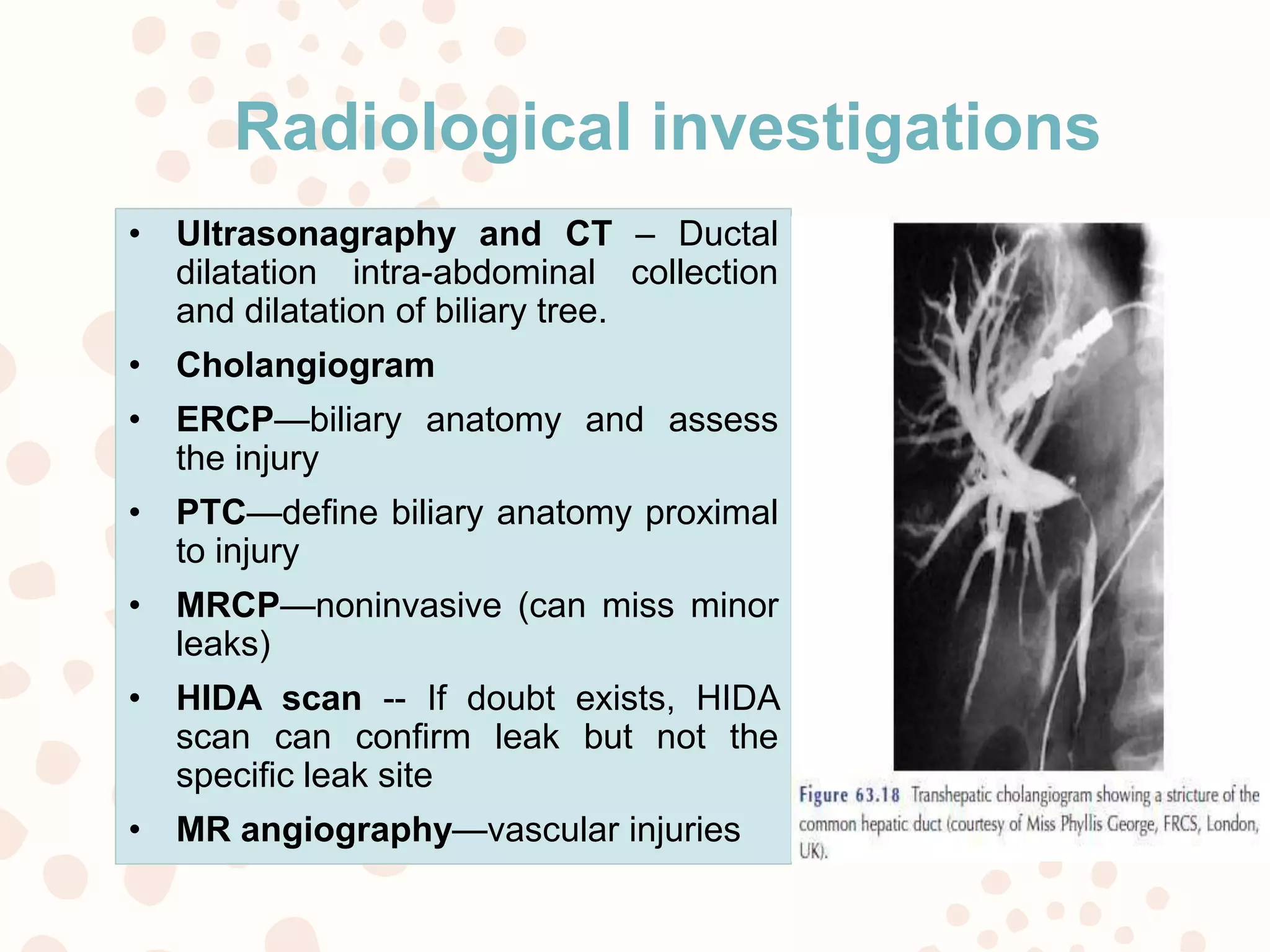

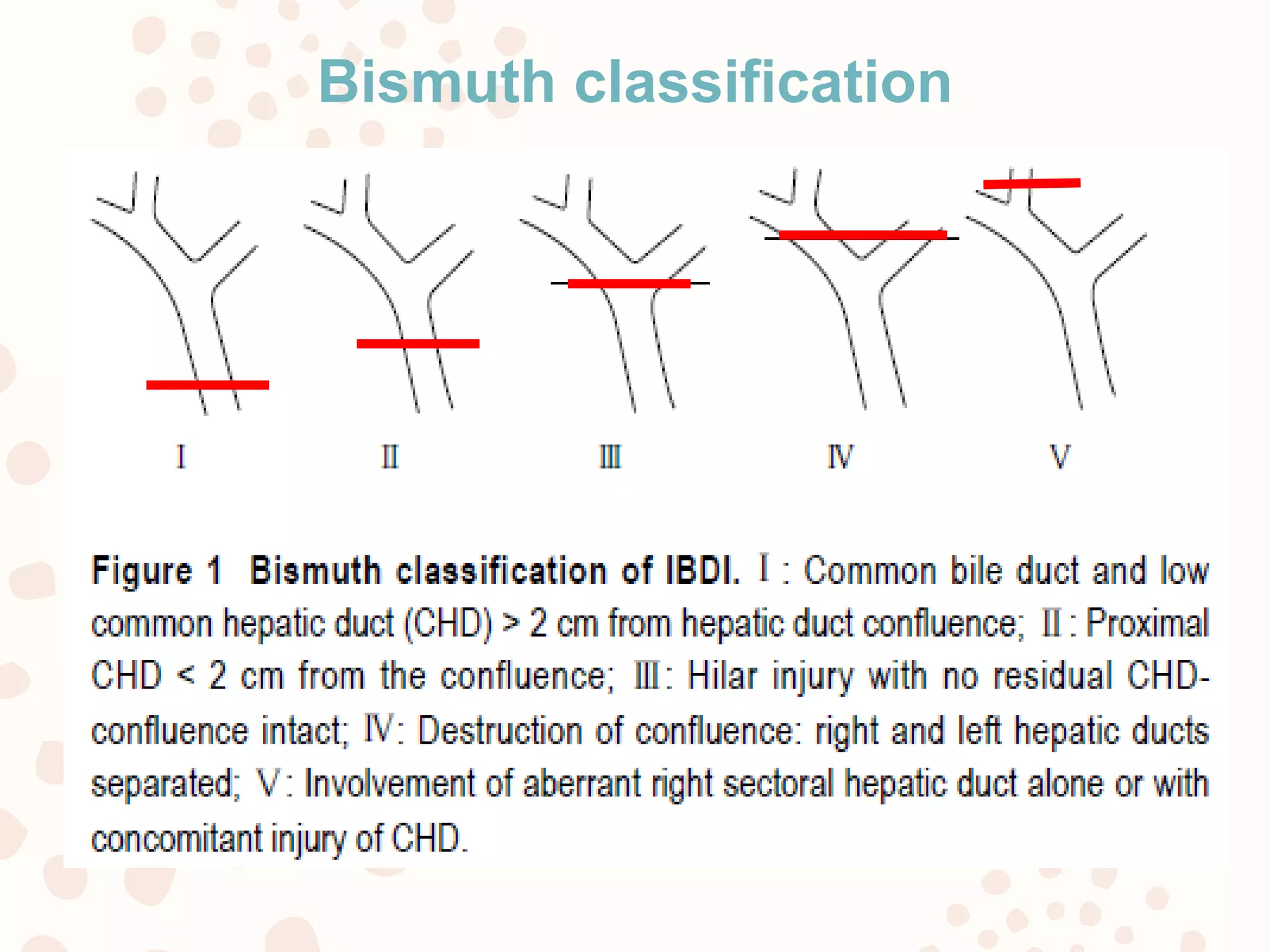

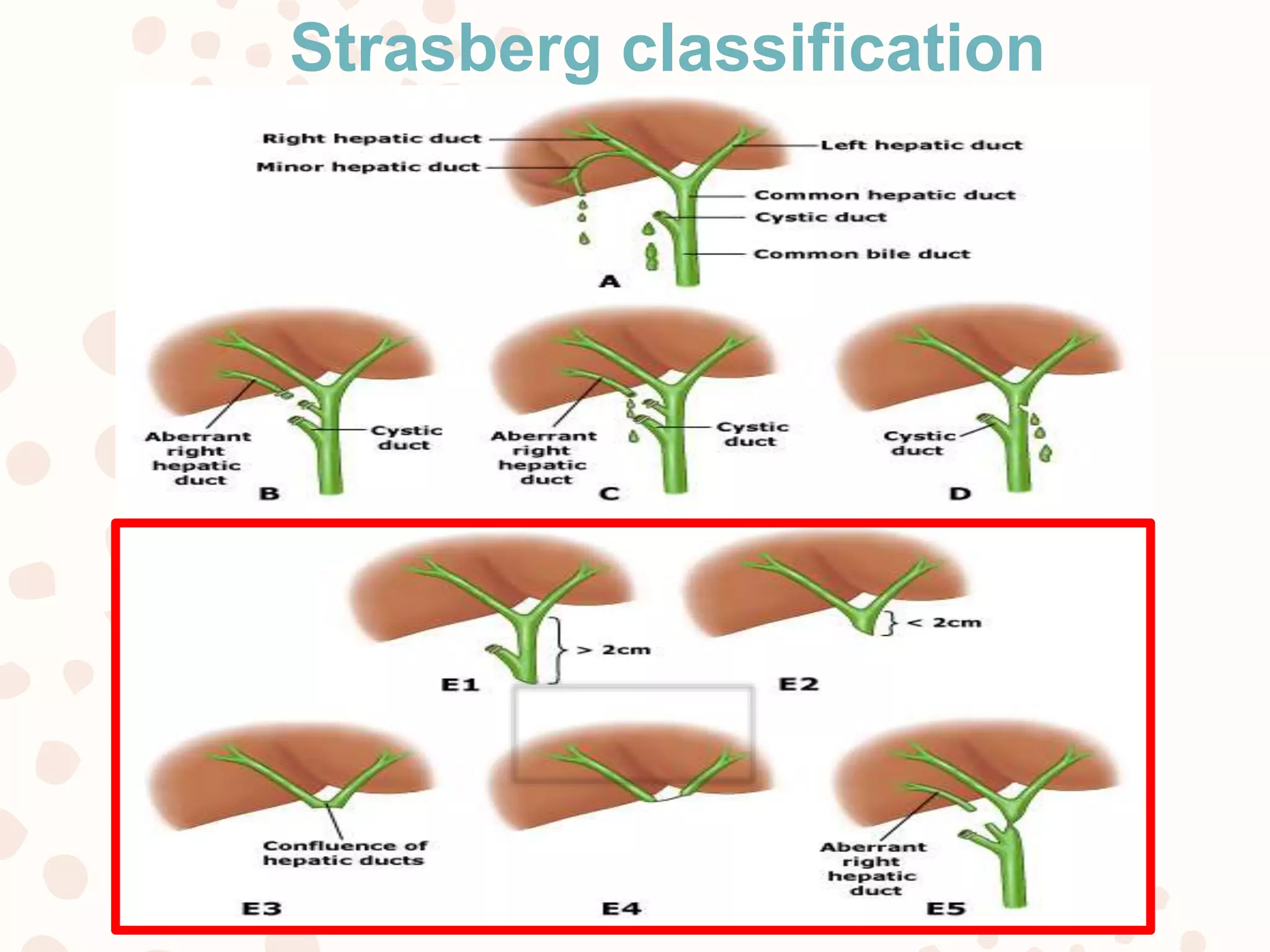

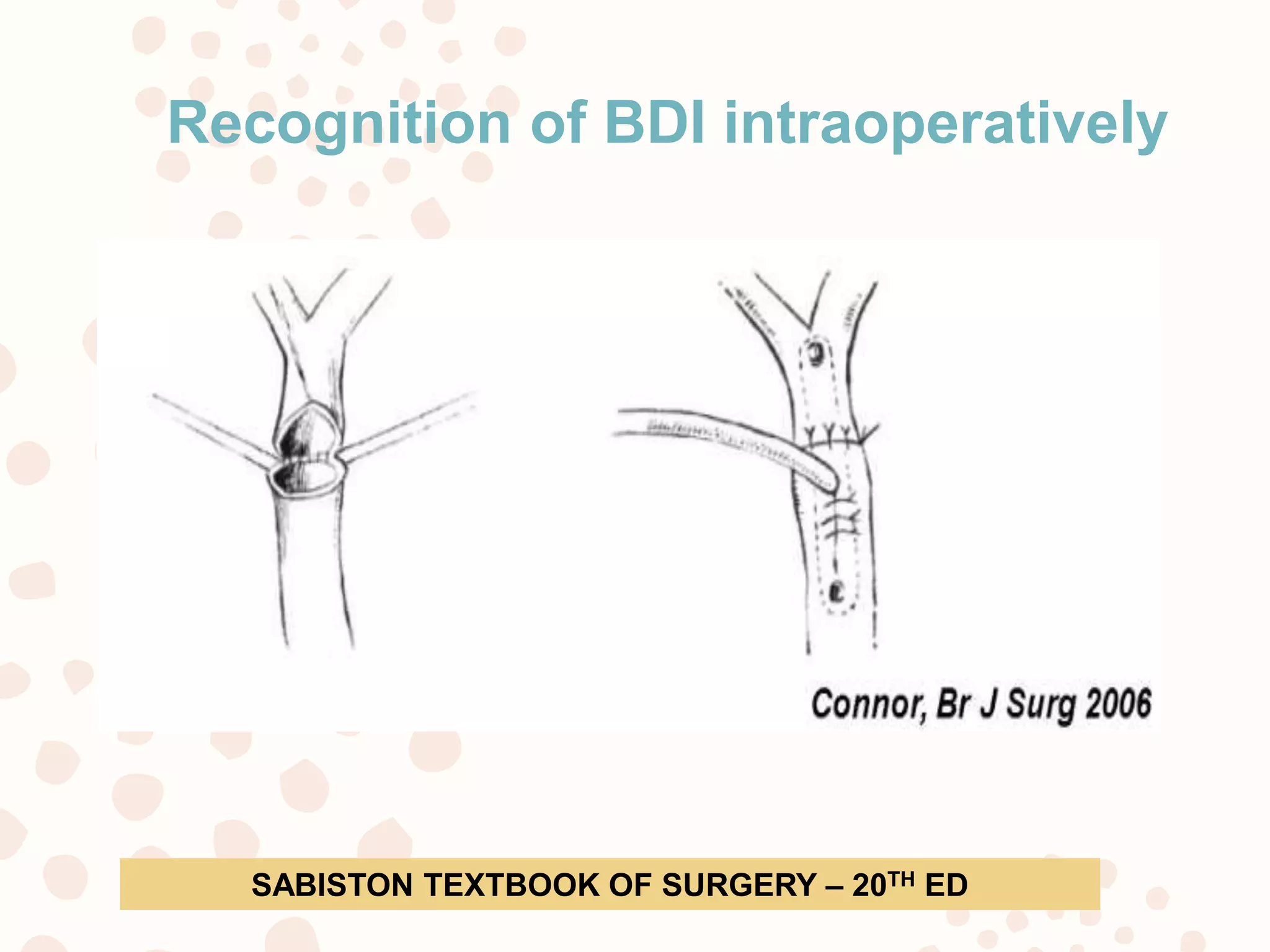

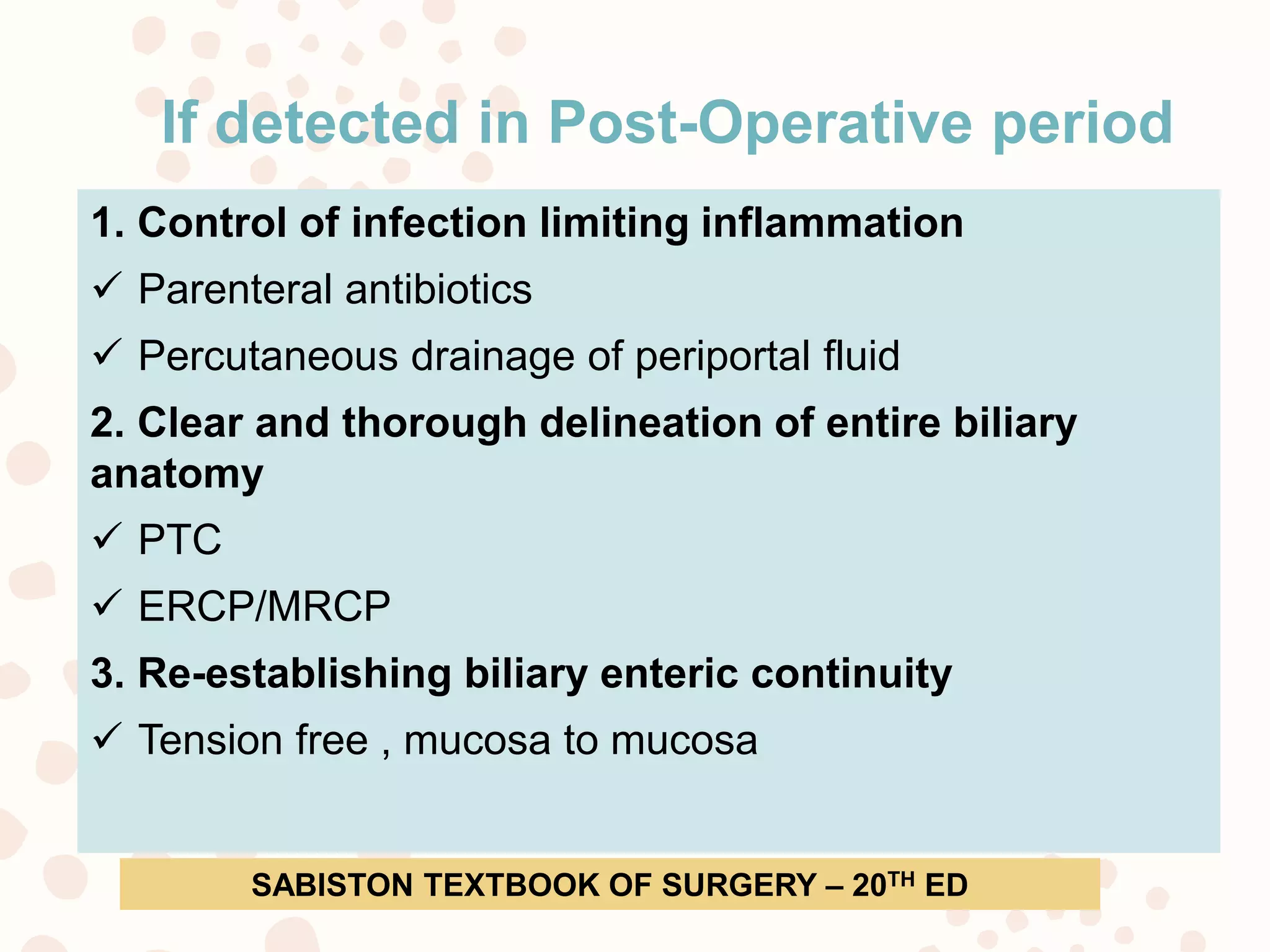

This document discusses safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy and management of bile duct injuries. It begins with an overview of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the increased risk of bile duct injury compared to open procedures. It then covers bile duct injury mechanisms, classifications, prevention techniques such as obtaining the critical view of safety, and management strategies whether the injury is recognized intraoperatively or postoperatively. The key messages are that obtaining the correct anatomical views and following established safety procedures can help prevent bile duct injuries, and injuries need to be promptly addressed either by repair or biliary reconstruction to reestablish bile flow.