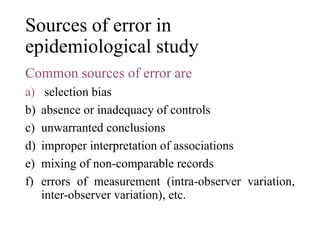

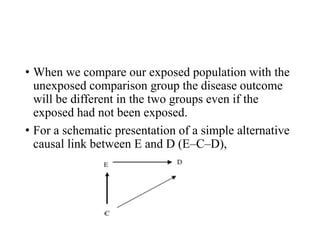

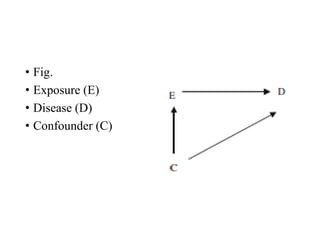

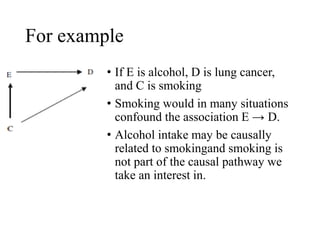

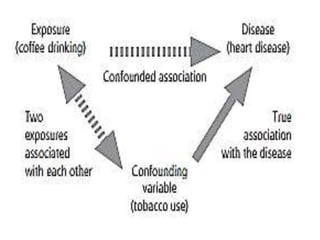

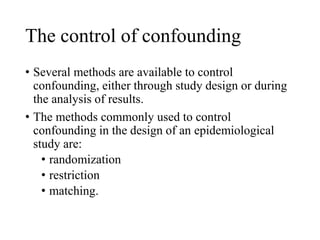

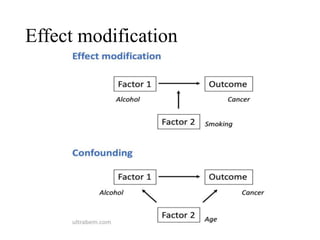

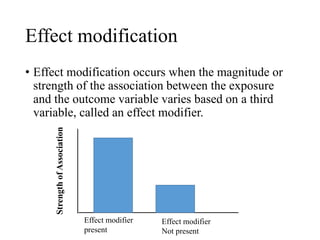

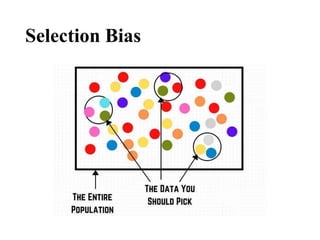

This document discusses bias, error, confounding, and effect modification in epidemiology, outlining various types of bias (recall, selection, measurement, confirmation, and halo effect) and their impact on study outcomes. It defines systematic and random errors, their sources, and offers methods for minimizing these biases through study design and analysis techniques, such as randomization, restriction, matching, stratification, and statistical modeling. Additionally, it describes the importance of confounding variables and effect modification in understanding the true relationship between exposure and disease outcomes.