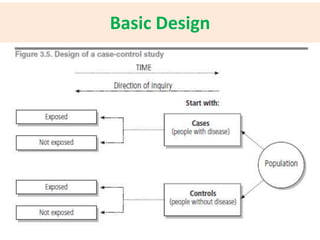

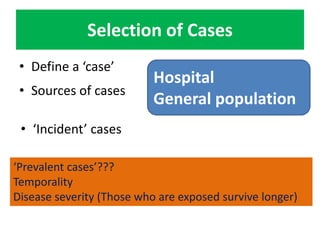

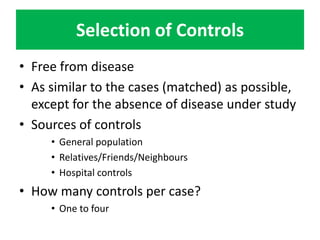

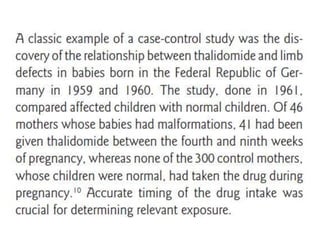

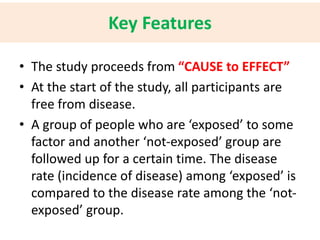

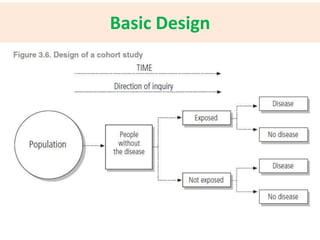

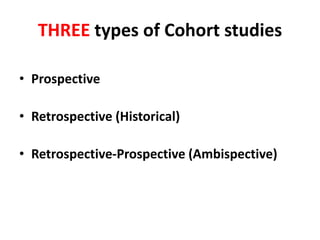

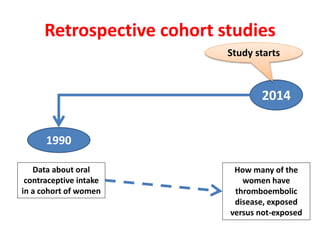

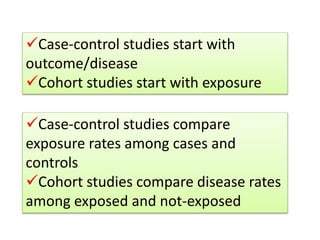

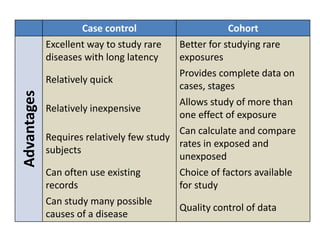

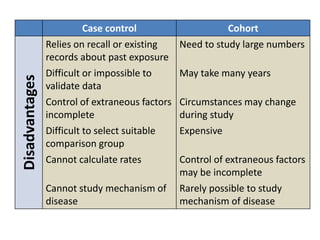

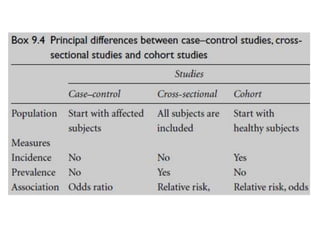

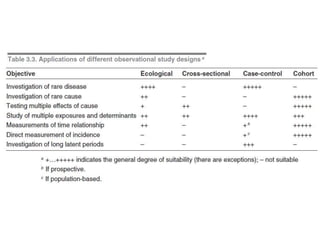

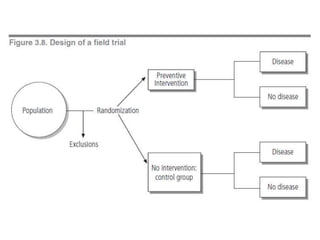

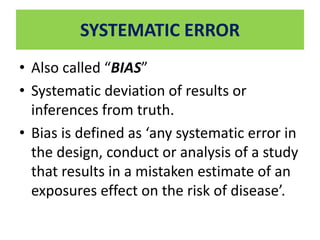

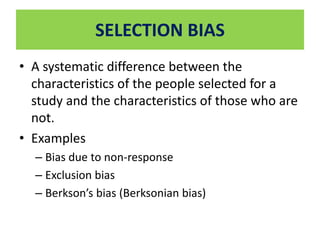

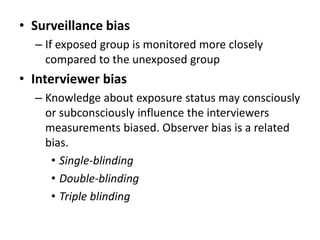

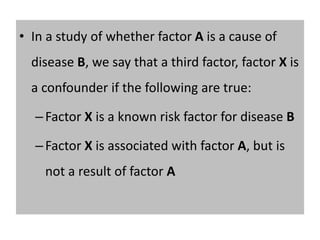

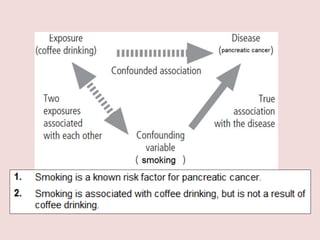

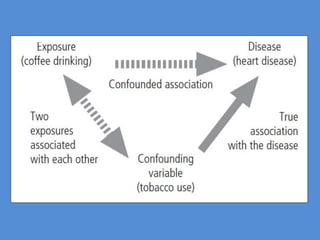

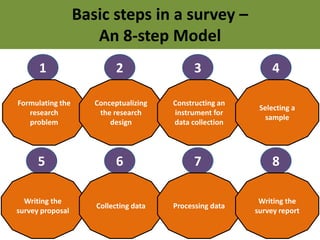

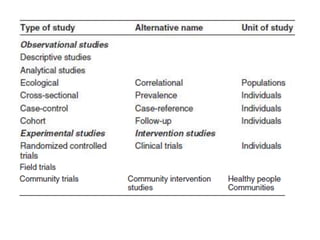

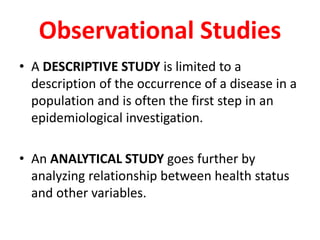

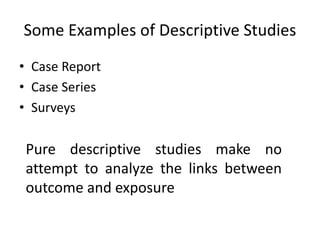

This document outlines different types of epidemiological study designs including observational studies like descriptive studies, analytical studies, ecological studies, cross-sectional studies and case-control studies. It also discusses experimental study designs like randomized controlled trials, field trials and community trials. Key features and steps are provided for case-control studies and cohort studies. Sources of bias and errors in epidemiological studies are also summarized.

![Key Features

• The exposure experience of a group of people

who have the disease [CASES] is compared to

the exposure experience of a similar

(matched) group who do not have the disease

[CONTROLS]

• Suitable for rare diseases or diseases with long

latency periods

• The study proceeds backwards from “EFFECT

to CAUSE’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/basicstepsinasurvey-141215031326-conversion-gate02/85/Epidemiological-Studies-15-320.jpg)