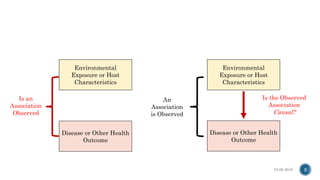

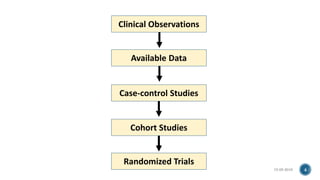

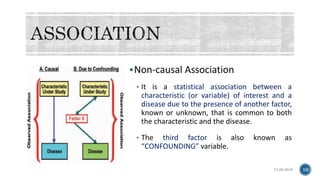

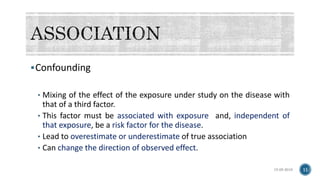

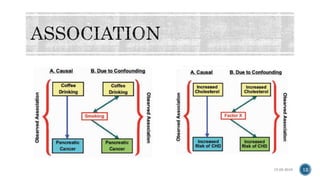

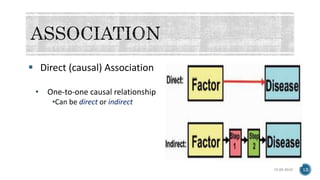

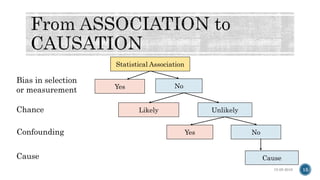

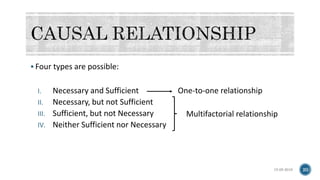

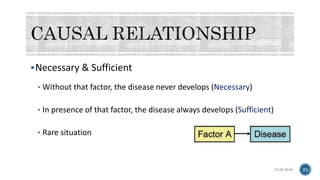

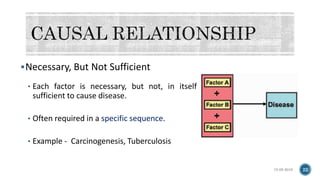

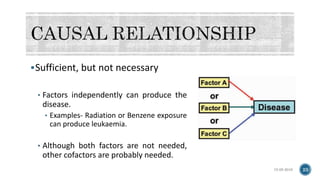

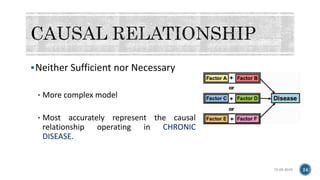

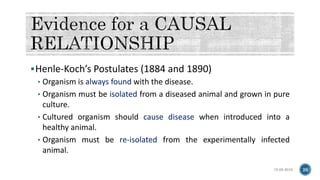

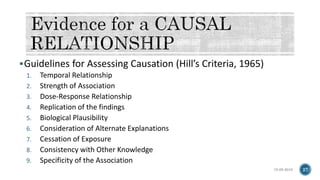

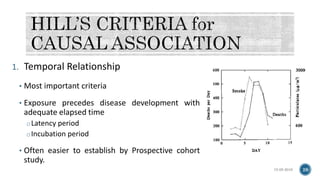

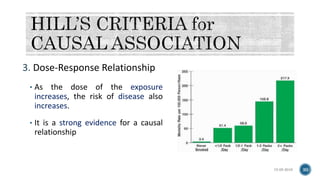

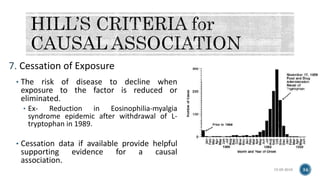

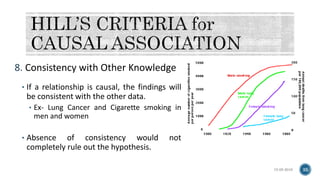

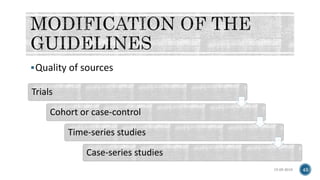

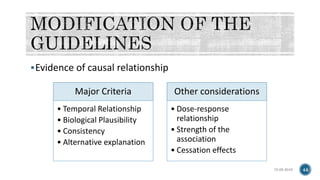

The document discusses the complex nature of causal relationships in epidemiology, differentiating between associations, correlations, and various types of causal associations. It outlines key concepts such as confounding factors and establishes guidelines for assessing causation based on criteria from Henle-Koch and Hill. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of evidence evaluation in determining causality, including considerations like temporal relationships, strength, and biological plausibility.