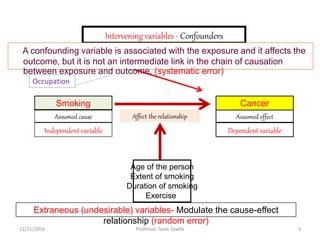

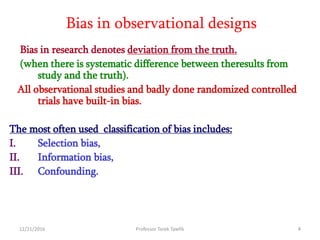

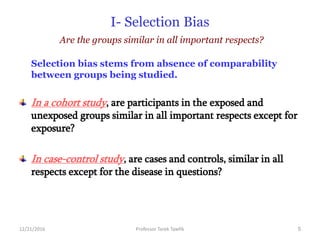

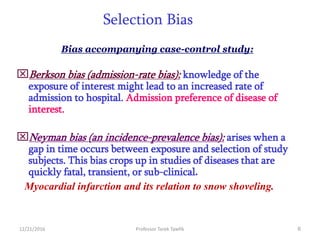

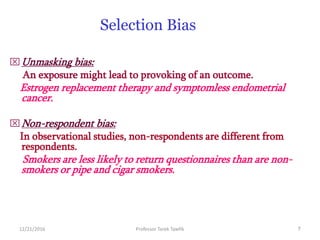

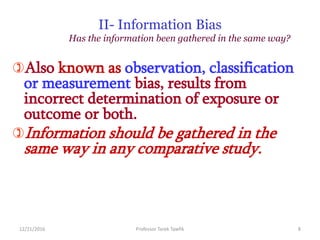

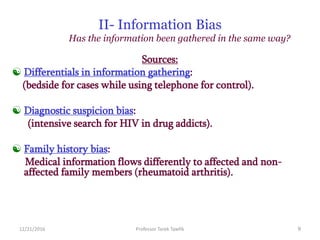

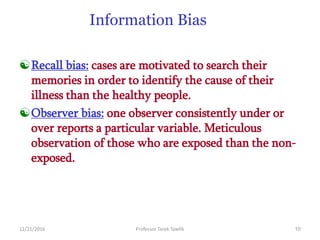

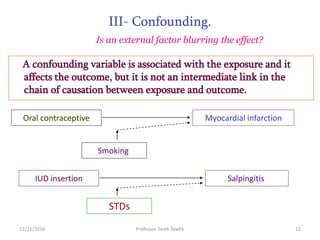

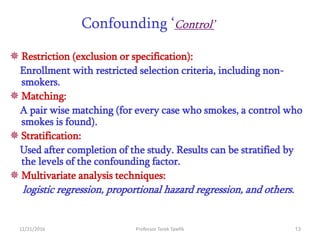

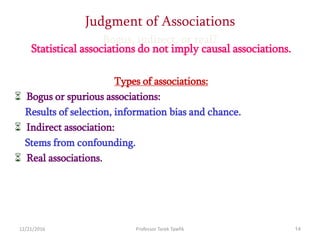

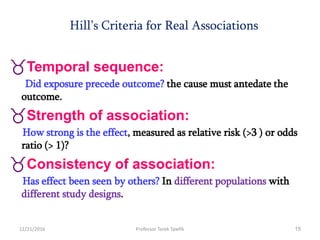

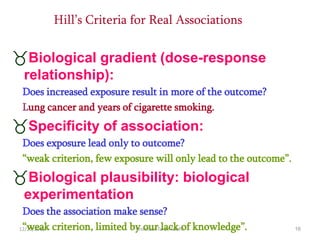

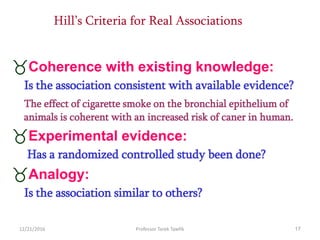

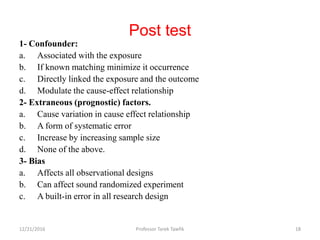

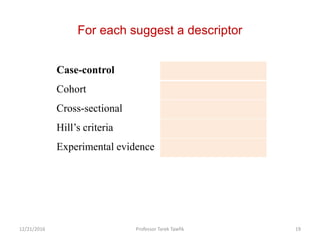

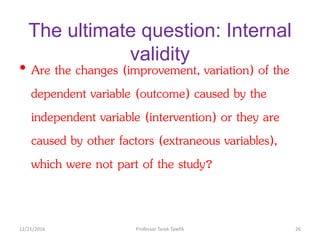

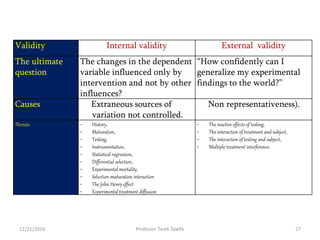

This document discusses various types of bias, confounding, and causation that can occur in epidemiological studies. It defines a confounder as a variable that is associated with the exposure and affects the outcome but is not in the causal pathway. Three main types of bias are described: selection bias, information bias, and confounding. Specific biases like recall bias, observer bias, and non-respondent bias are explained. Methods for controlling confounding like matching, stratification, and multivariate analysis are also outlined. The document concludes by discussing Hill's criteria for determining a causal association and threats to the internal and external validity of experimental studies.

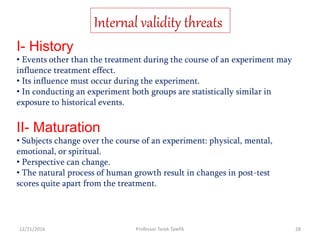

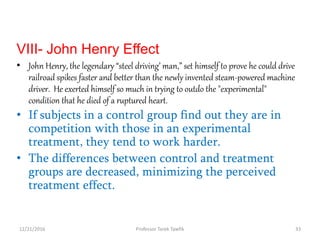

![V- Statistical regression [regression towards the

mean]

• Statistical regression refers to the tendency of extreme scores,

whether low or high, to move toward the average on a second

testing.

• Subjects who score very high or very low on one test will

probably score less high or low when they take the test again.

That is, they regress toward the mean.

• Do not study groups formed from extreme scores. Study the full

range of scores.

12/21/2016 30Professor Tarek Tawfik](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biasconfounding-161221060803/85/Bias-and-confounding-30-320.jpg)

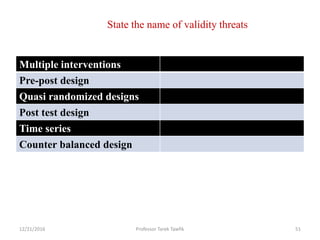

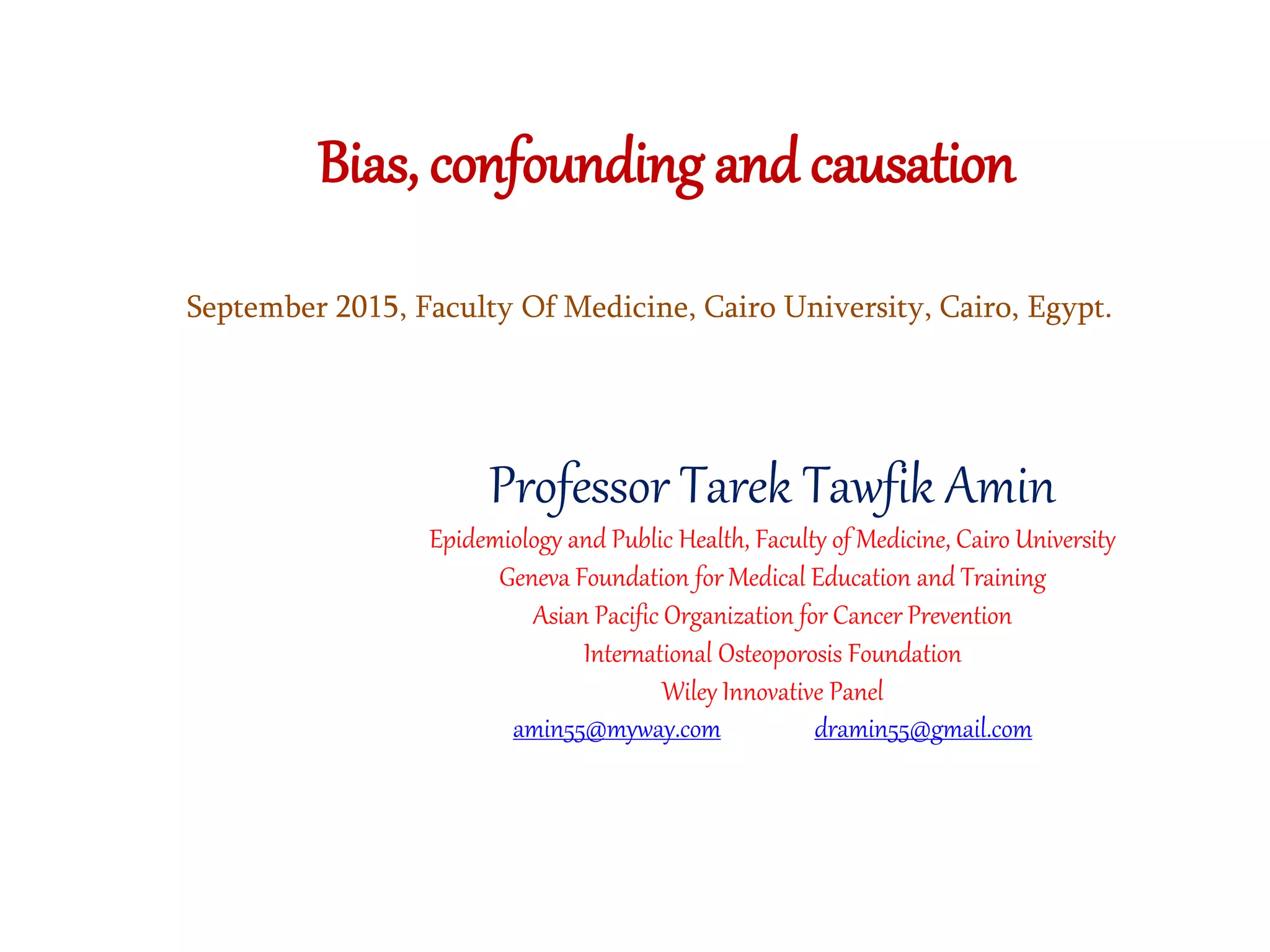

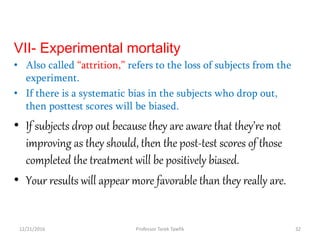

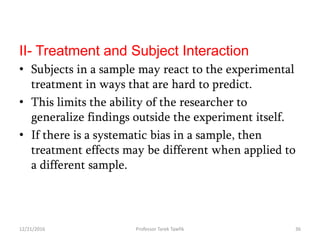

![Counter balanced design

Group 2

Group 1

Treatment 1

Assessment 1

Treatment 1

Assessment 1

Treatment 2

Assessment 2

Treatment 2

Assessment 2

Group 2

Group 1

Time

Latin Square Analysis

Selection Maturation Interaction

Multiple treatments (interventions) effect [external validity]

12/21/2016 45Professor Tarek Tawfik](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biasconfounding-161221060803/85/Bias-and-confounding-45-320.jpg)