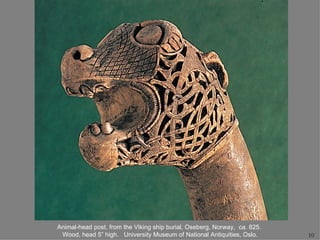

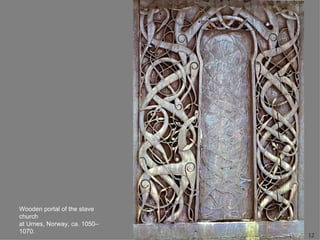

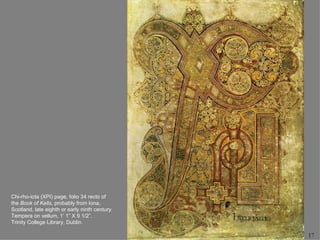

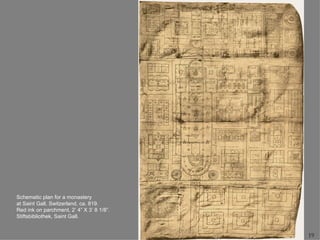

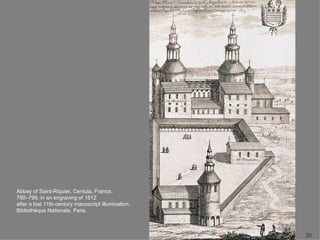

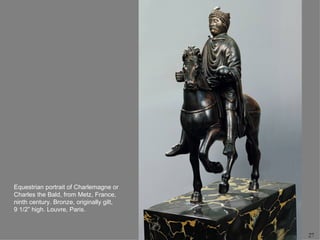

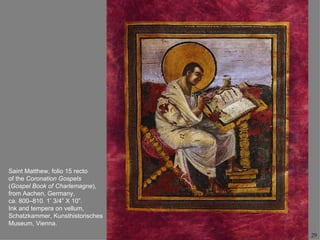

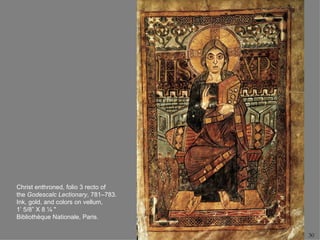

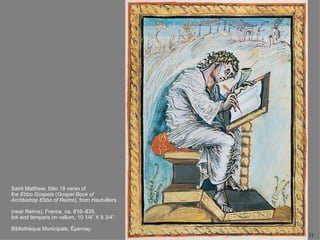

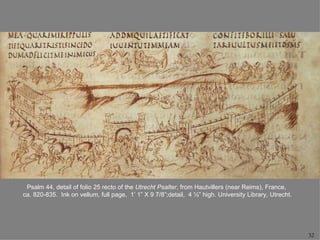

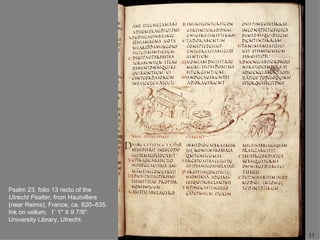

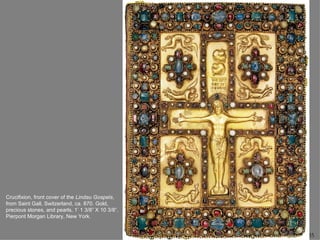

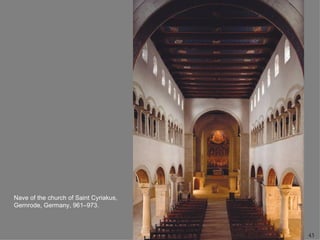

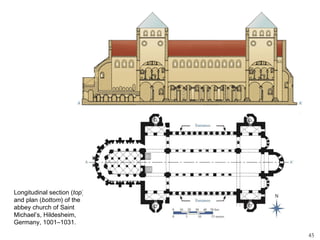

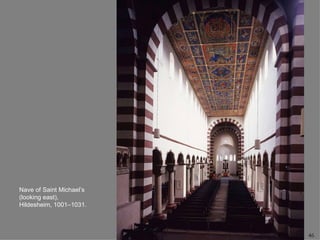

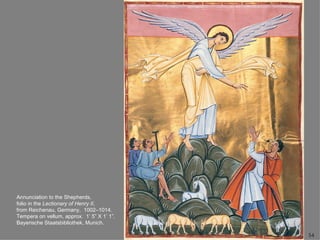

Early Medieval Art developed after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the Romanesque period of the 11th century. Christian monks played a key role in preserving art by creating illuminated manuscripts. Northern European peoples like the Merovingians and Anglo-Saxons developed artistic styles using interlaced designs and abstract animal imagery. Under Charlemagne's empire, Carolingian art revived Roman forms and focused on book illuminations. Ottonian art flourished in Germany with architectural styles influenced by Byzantium and illuminated manuscripts featuring linear figures.