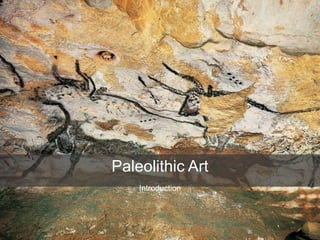

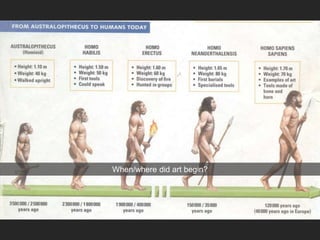

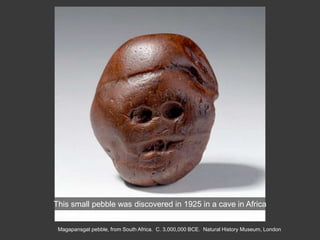

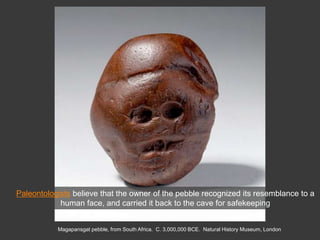

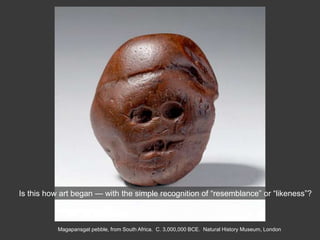

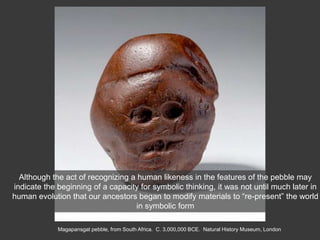

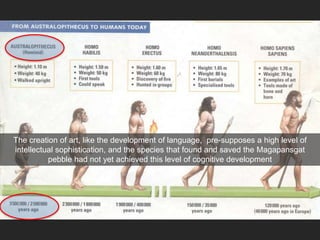

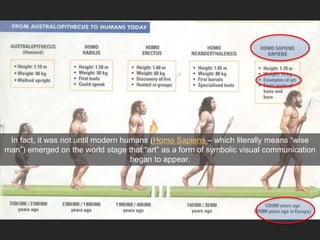

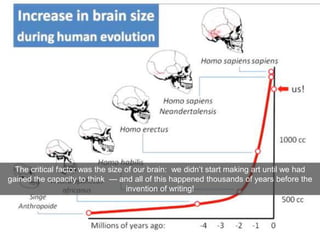

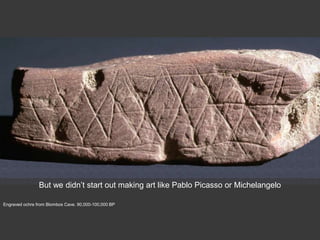

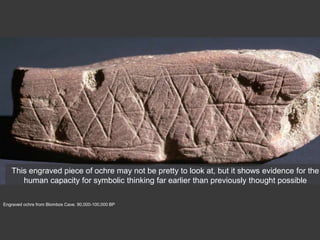

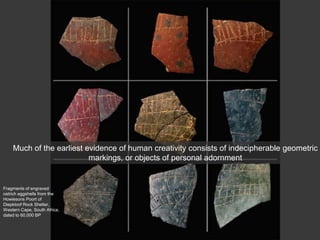

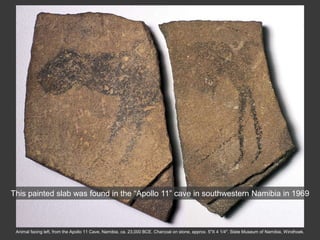

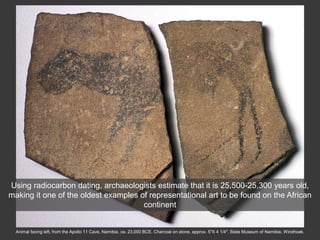

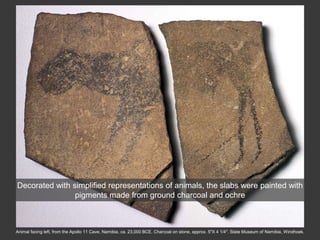

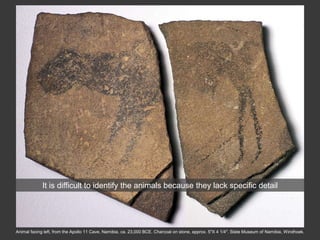

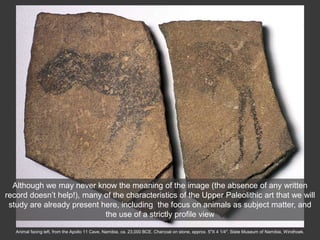

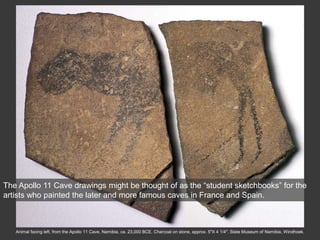

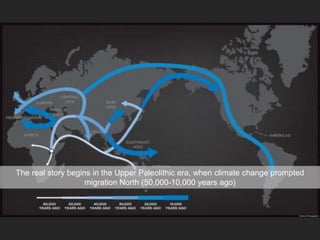

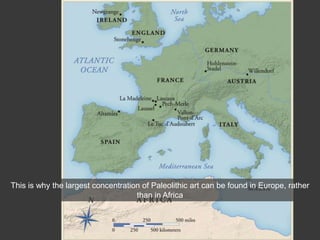

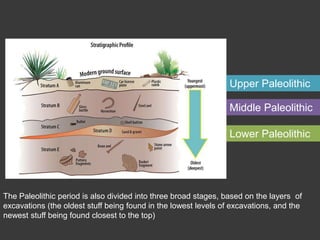

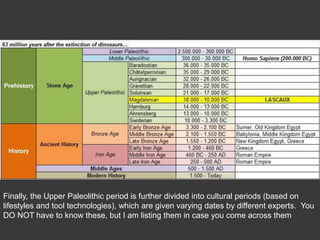

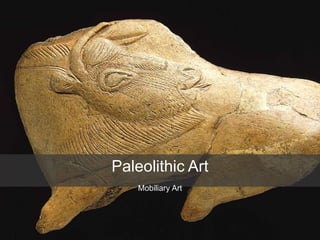

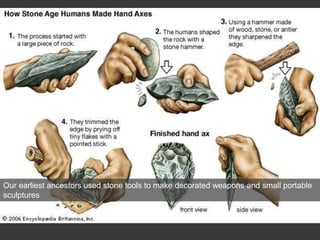

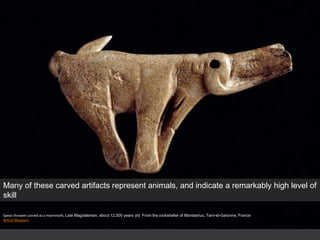

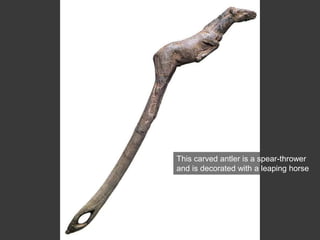

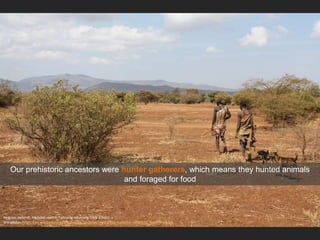

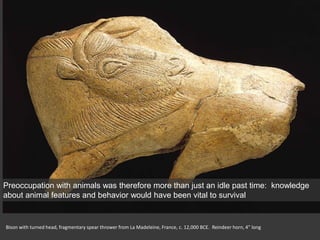

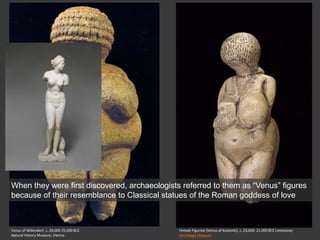

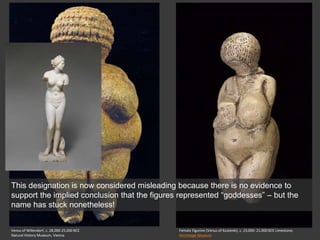

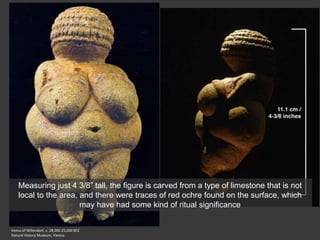

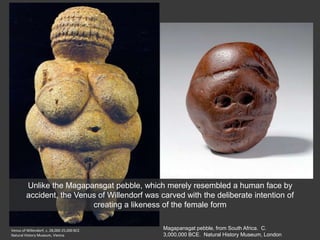

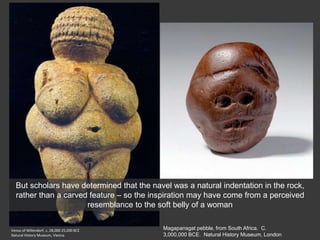

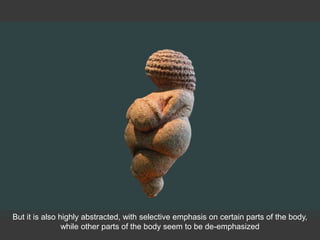

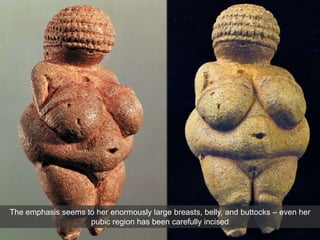

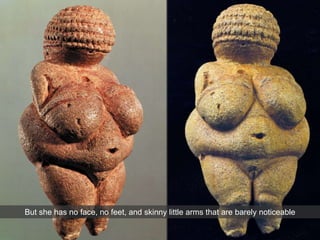

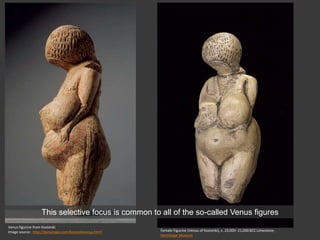

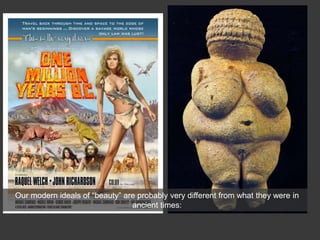

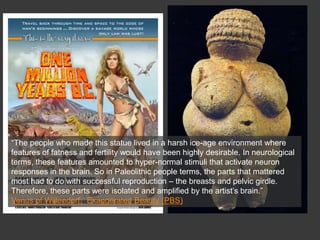

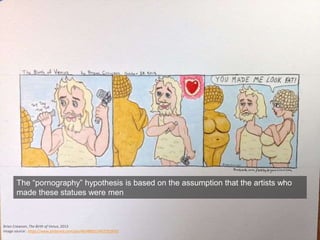

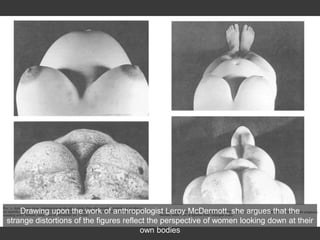

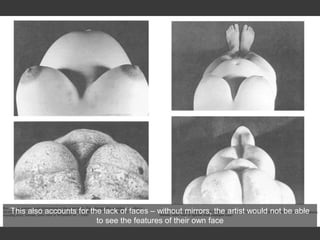

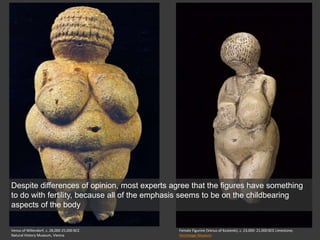

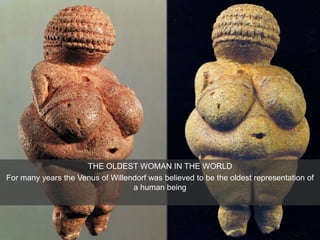

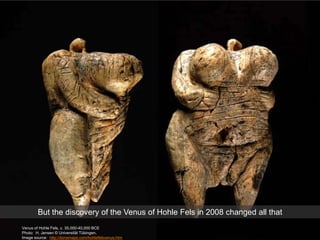

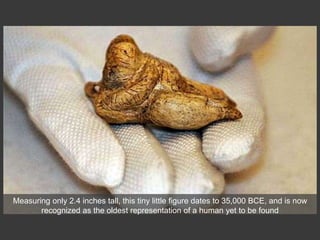

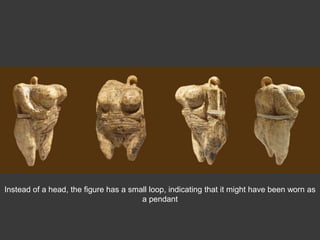

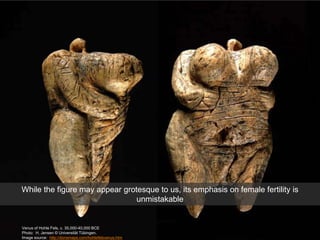

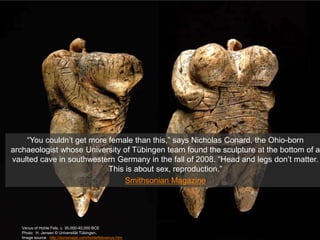

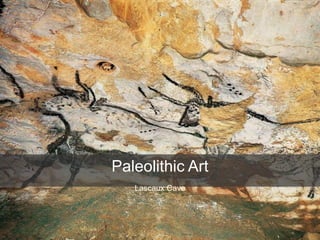

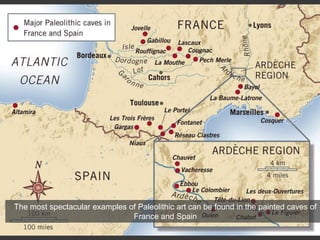

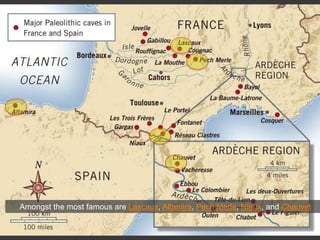

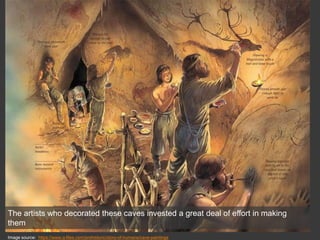

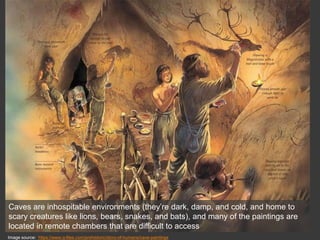

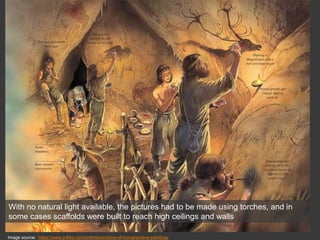

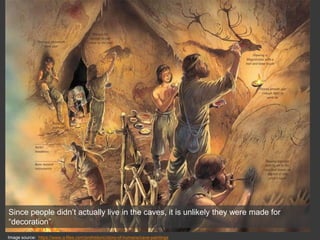

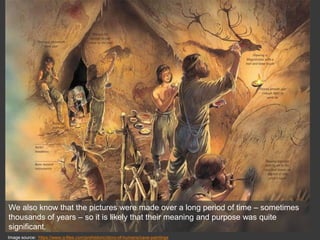

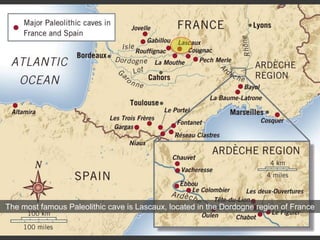

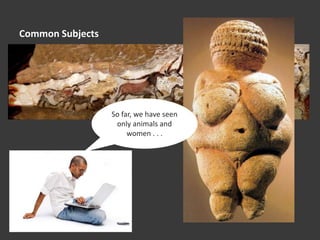

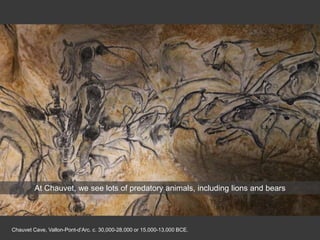

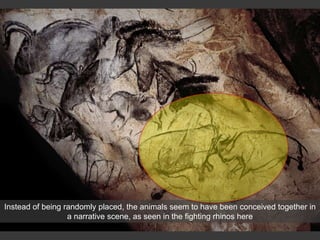

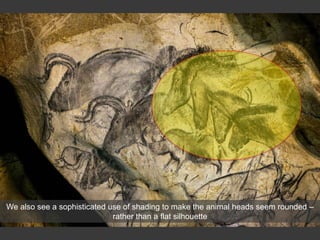

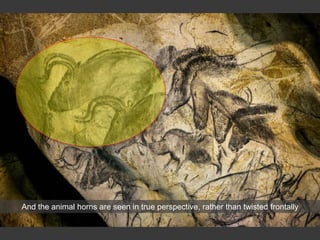

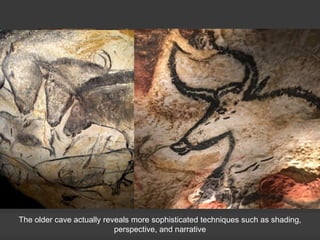

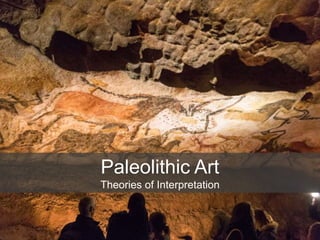

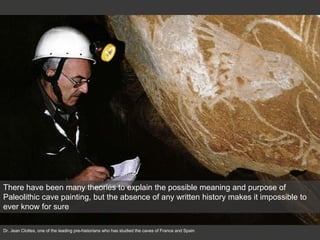

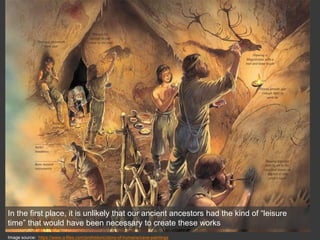

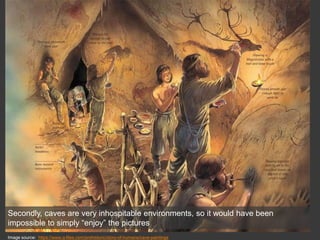

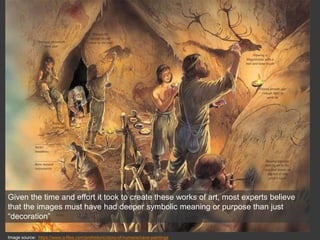

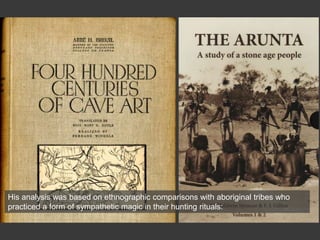

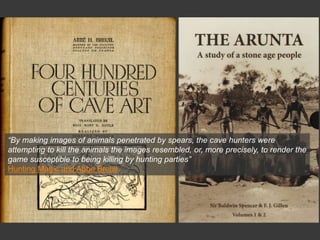

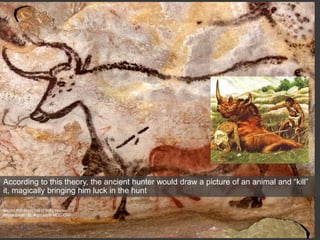

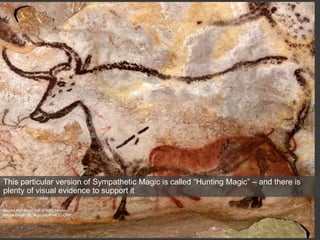

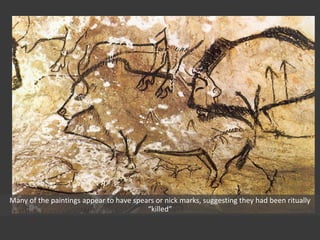

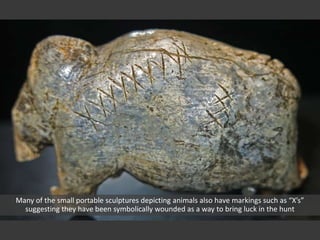

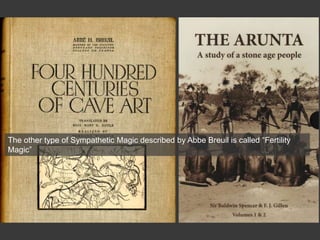

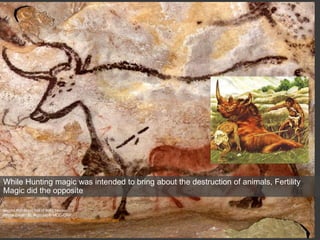

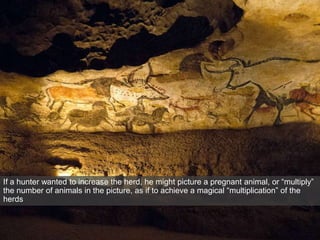

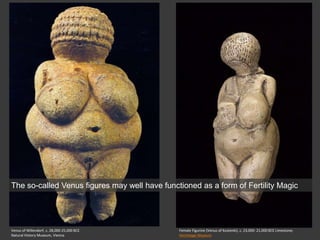

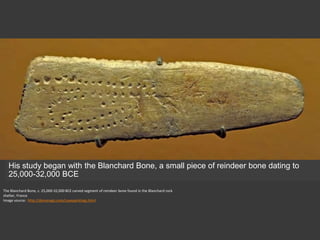

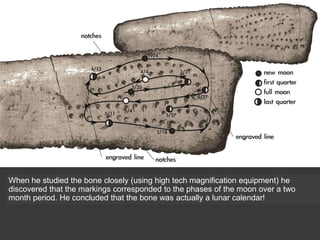

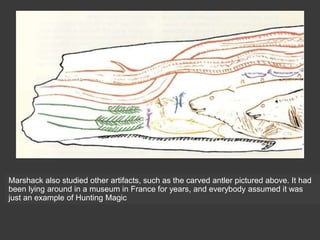

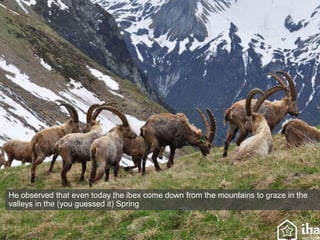

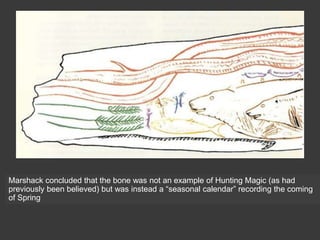

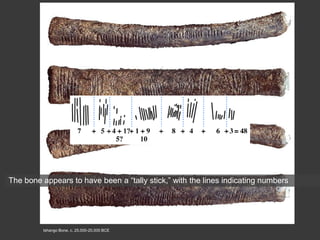

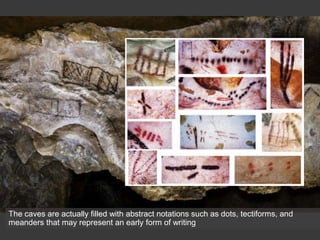

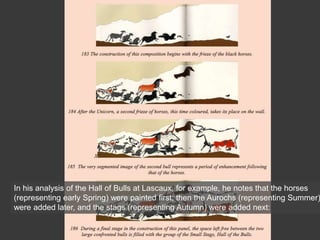

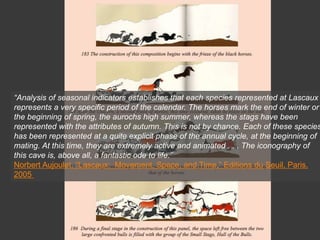

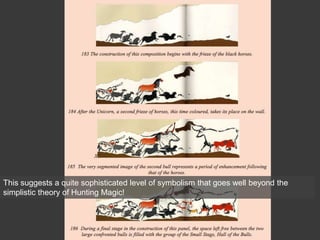

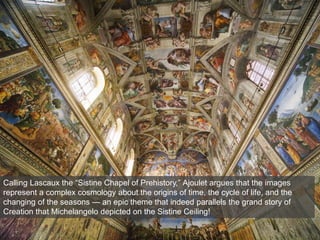

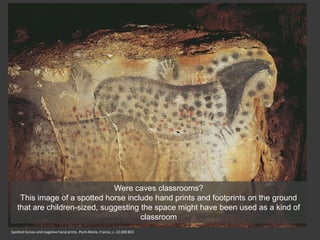

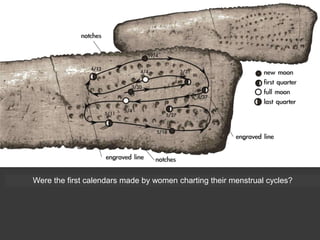

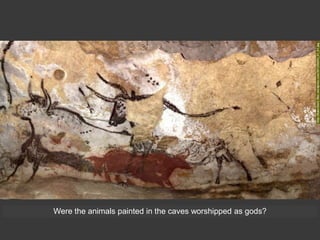

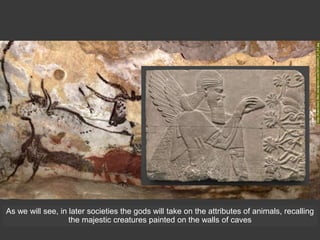

This document provides an overview of early paleolithic art beginning in Africa. It discusses the Magapansgat pebble from South Africa dated to 3 million years ago, which some believe represents early symbolic thinking. Mobiliary art, or small portable sculptures, emerged later, often depicting animals which were important for survival. Female figurines also appeared, like the Venus of Willendorf dated to 28,000 BCE, which focused heavily on fertility features. Scholars debate the meaning and purpose of these figurines. The document outlines the evolution of increasingly sophisticated art in Europe during the Upper Paleolithic period beginning around 50,000 years ago, reflecting the cognitive developments of modern humans.