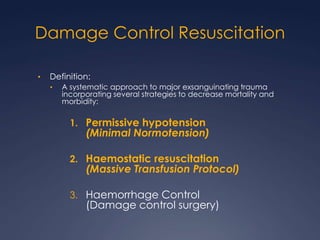

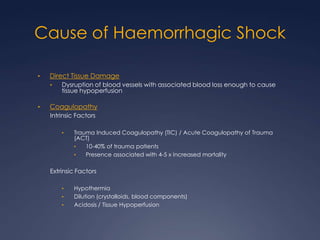

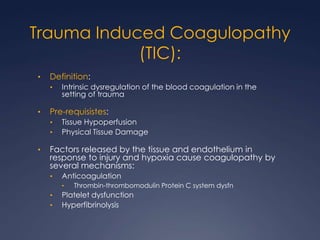

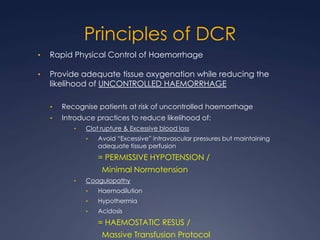

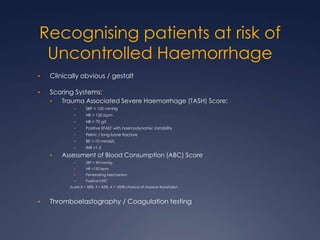

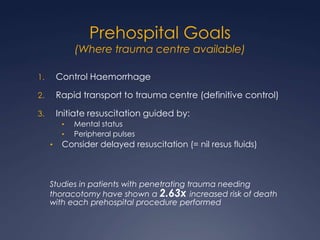

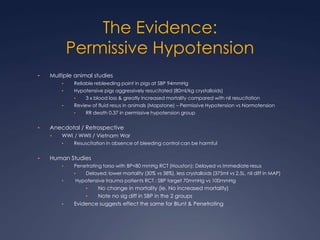

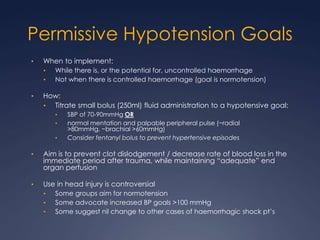

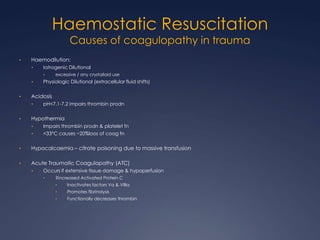

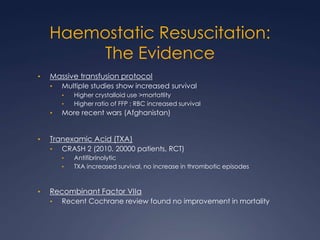

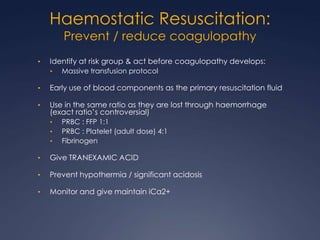

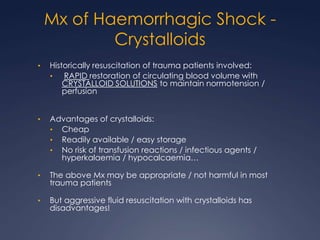

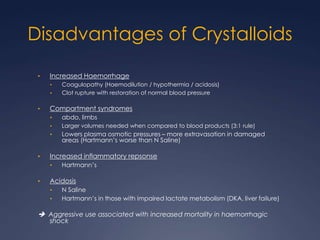

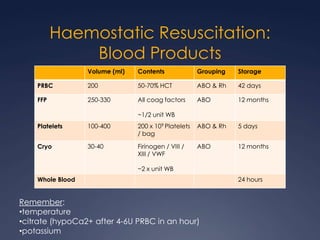

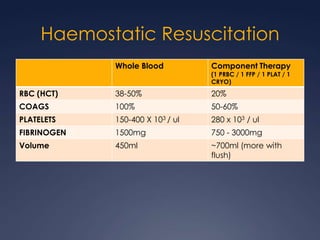

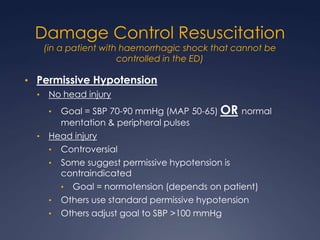

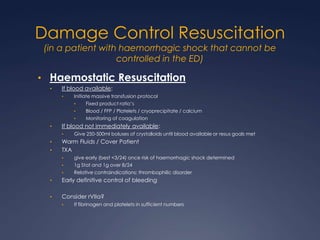

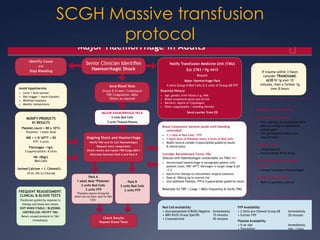

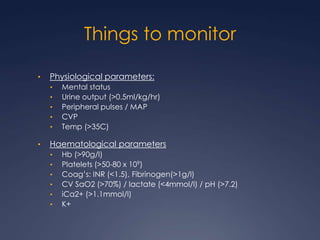

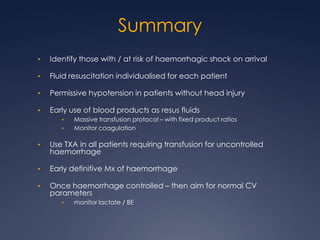

Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) is a systematic approach for managing major trauma patients at risk of exsanguinating hemorrhage. It incorporates permissive hypotension to minimize blood loss while hemorrhage is uncontrolled, haemostatic resuscitation using blood products instead of crystalloids to prevent coagulopathy, and early hemorrhage control through surgery. DCR aims to decrease mortality and morbidity by recognizing patients at risk of hemorrhagic shock, providing adequate tissue oxygenation through hypotensive resuscitation while limiting further blood loss and clot disruption, and preventing the triad of hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy through haemostatic resuscitation and blood product administration according to a