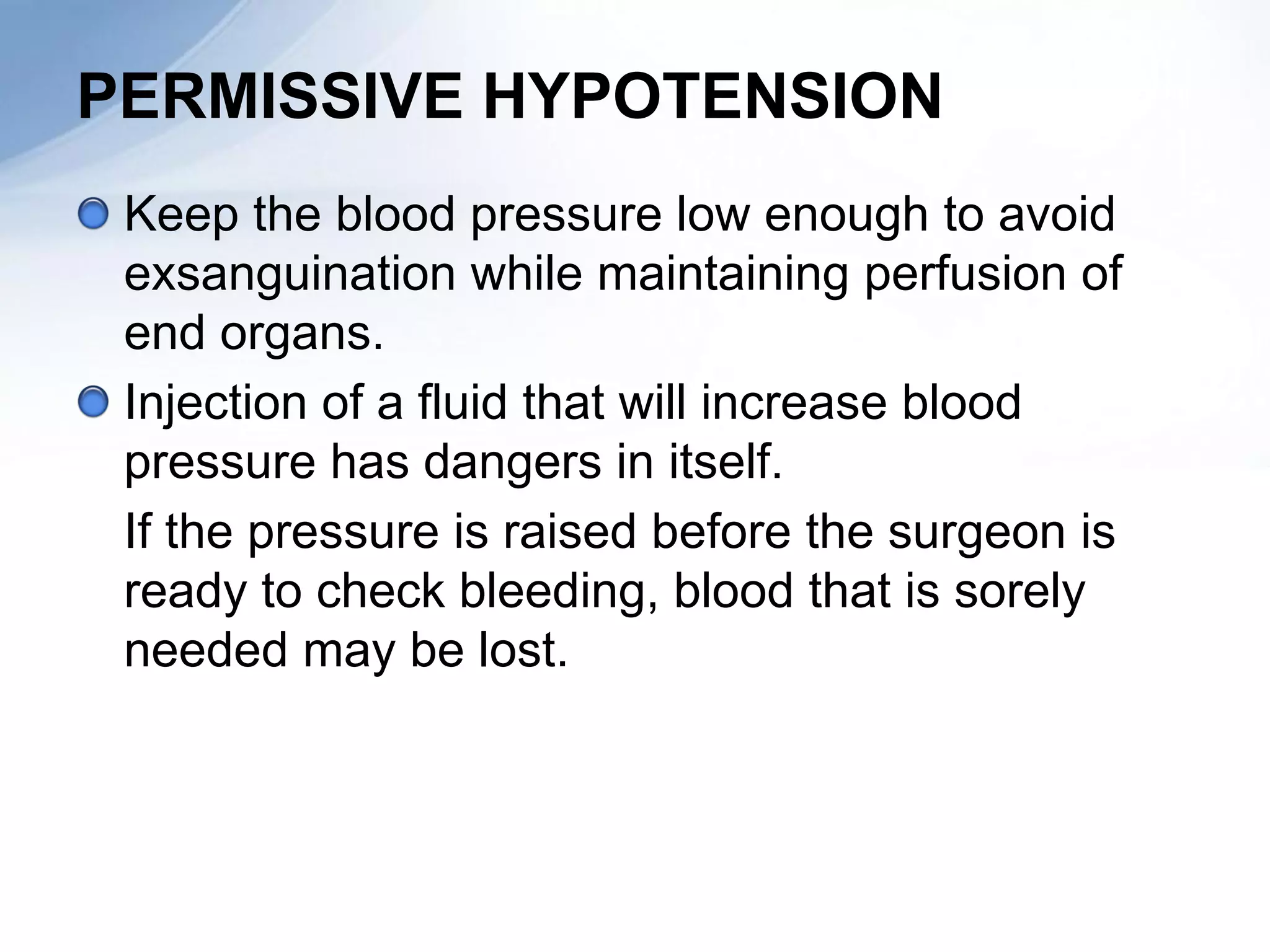

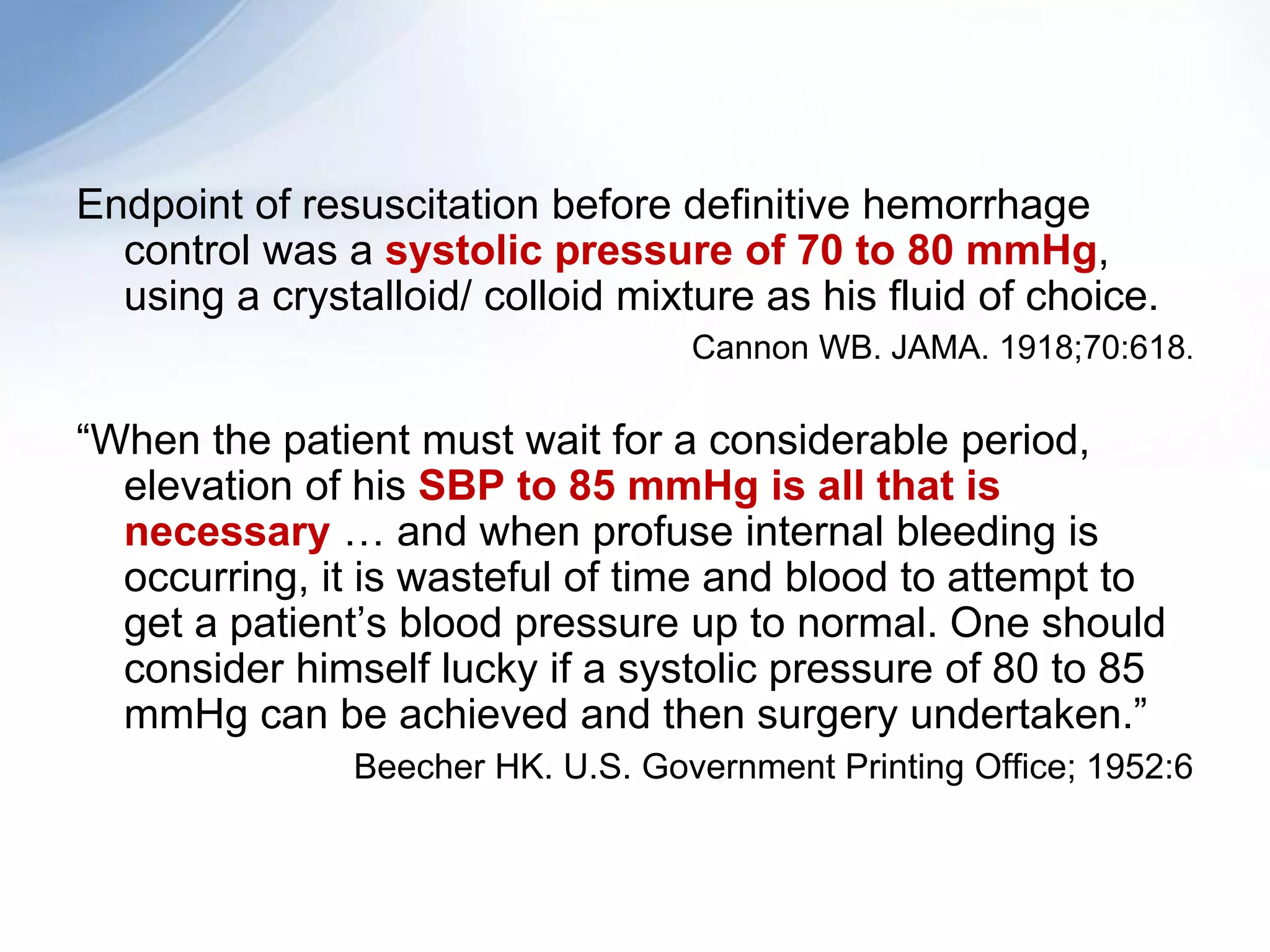

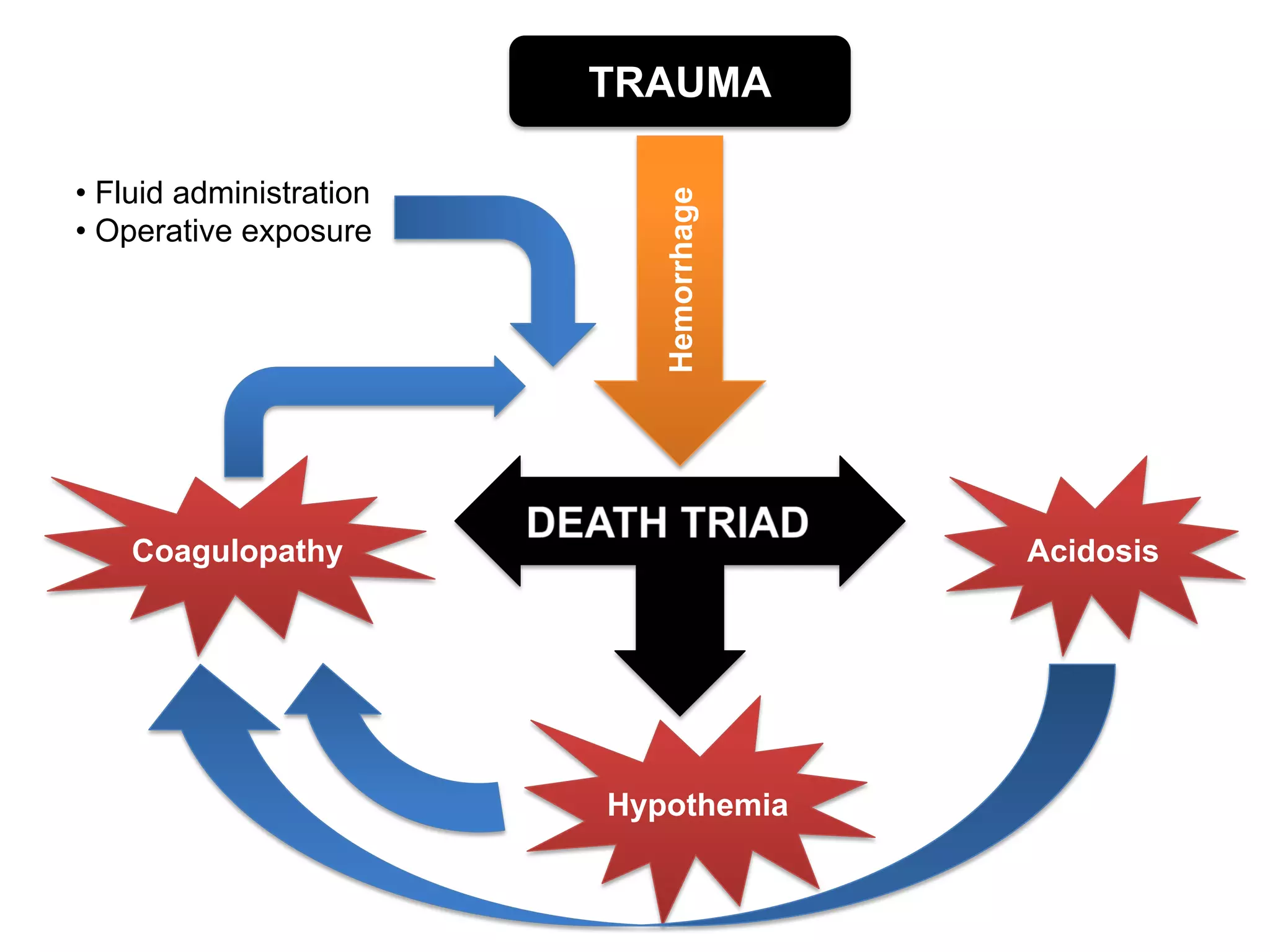

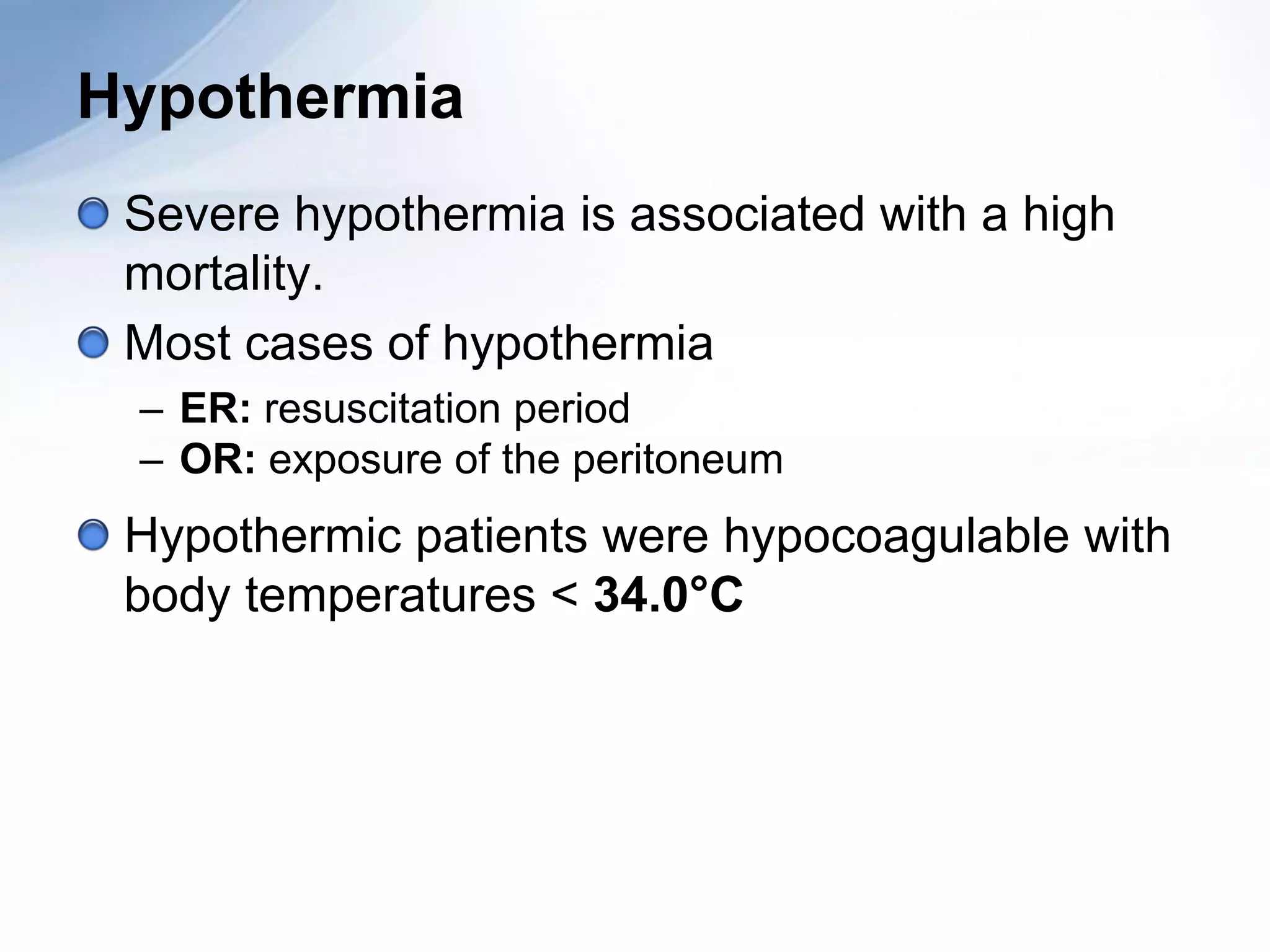

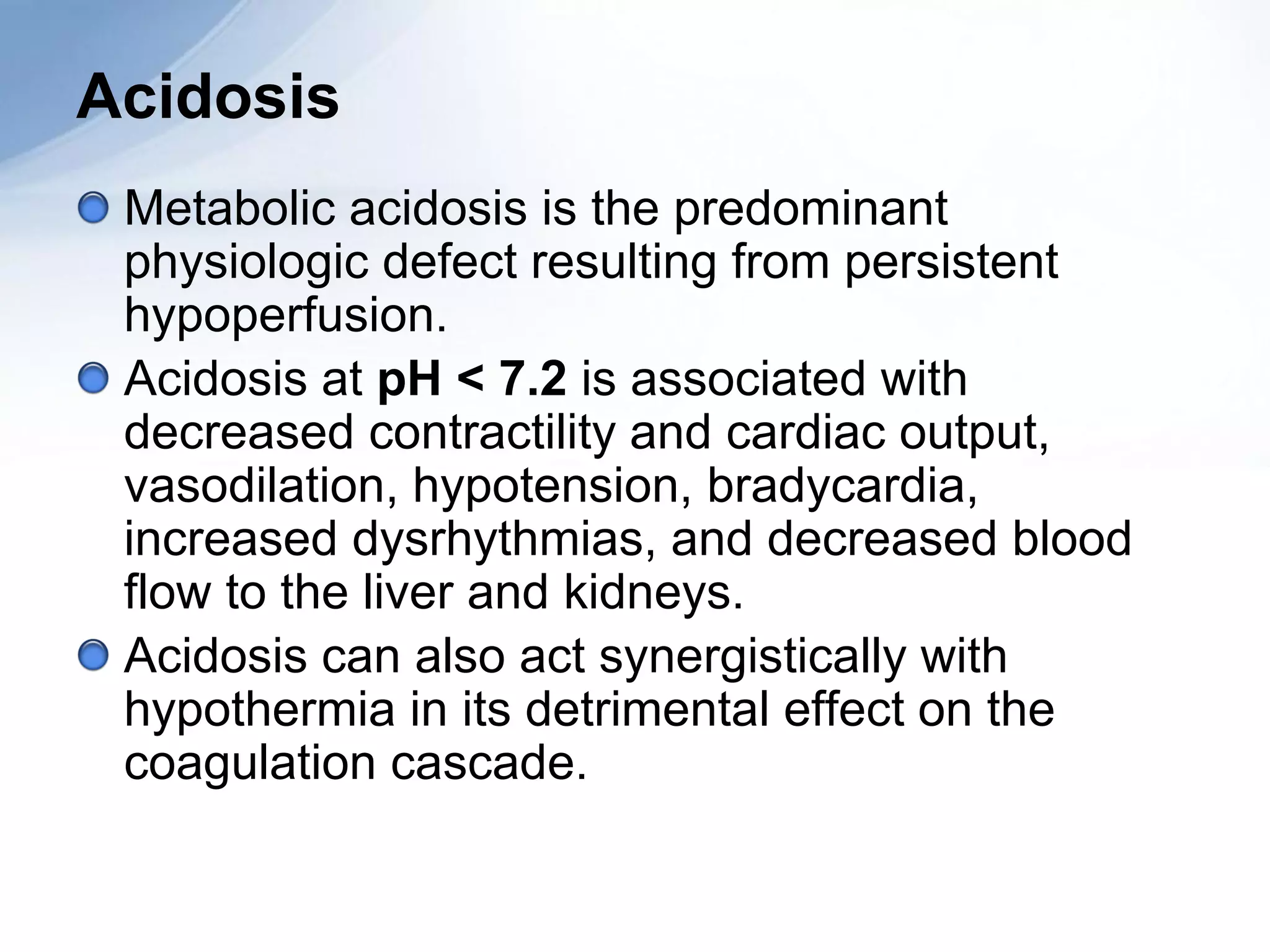

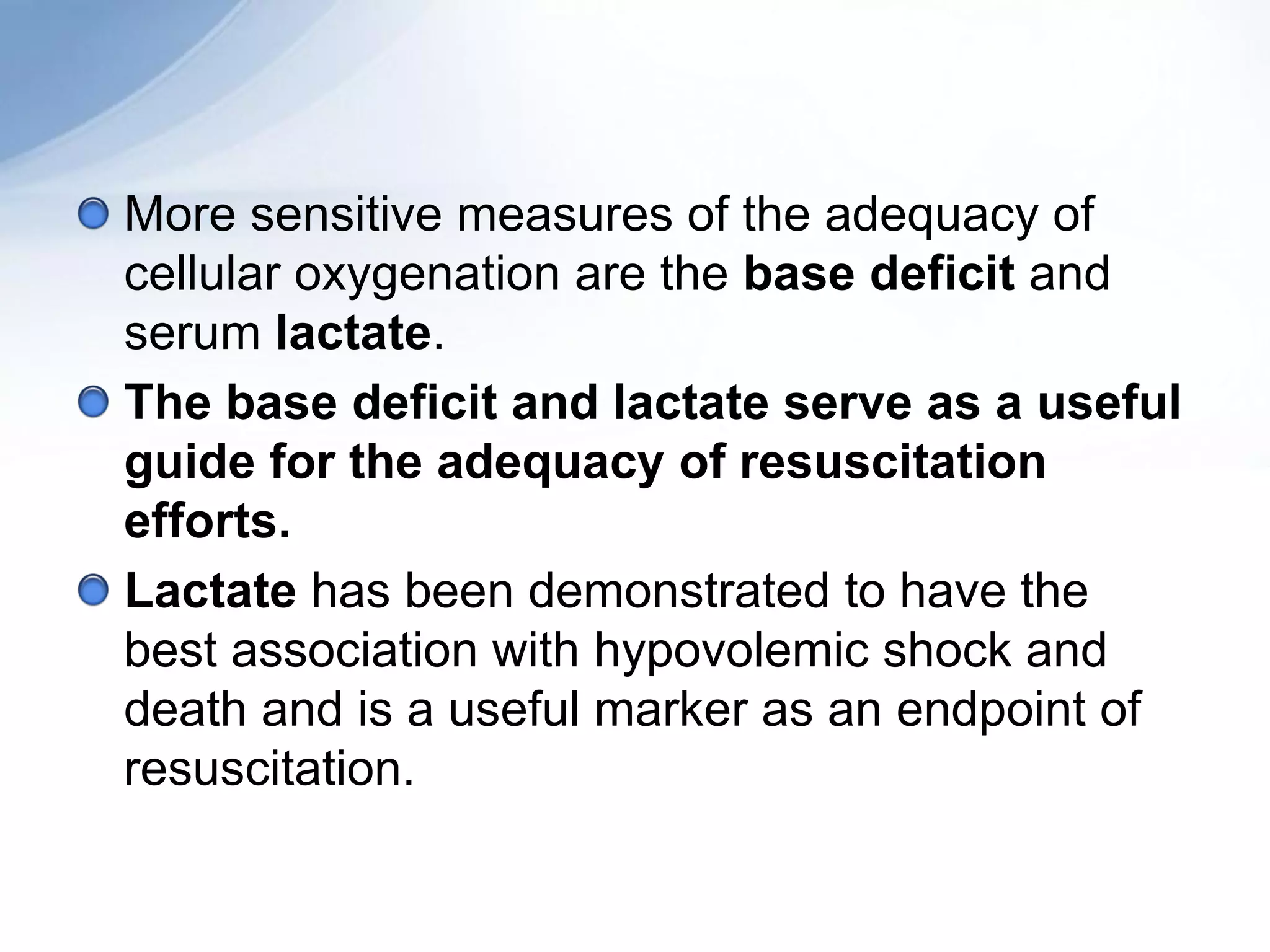

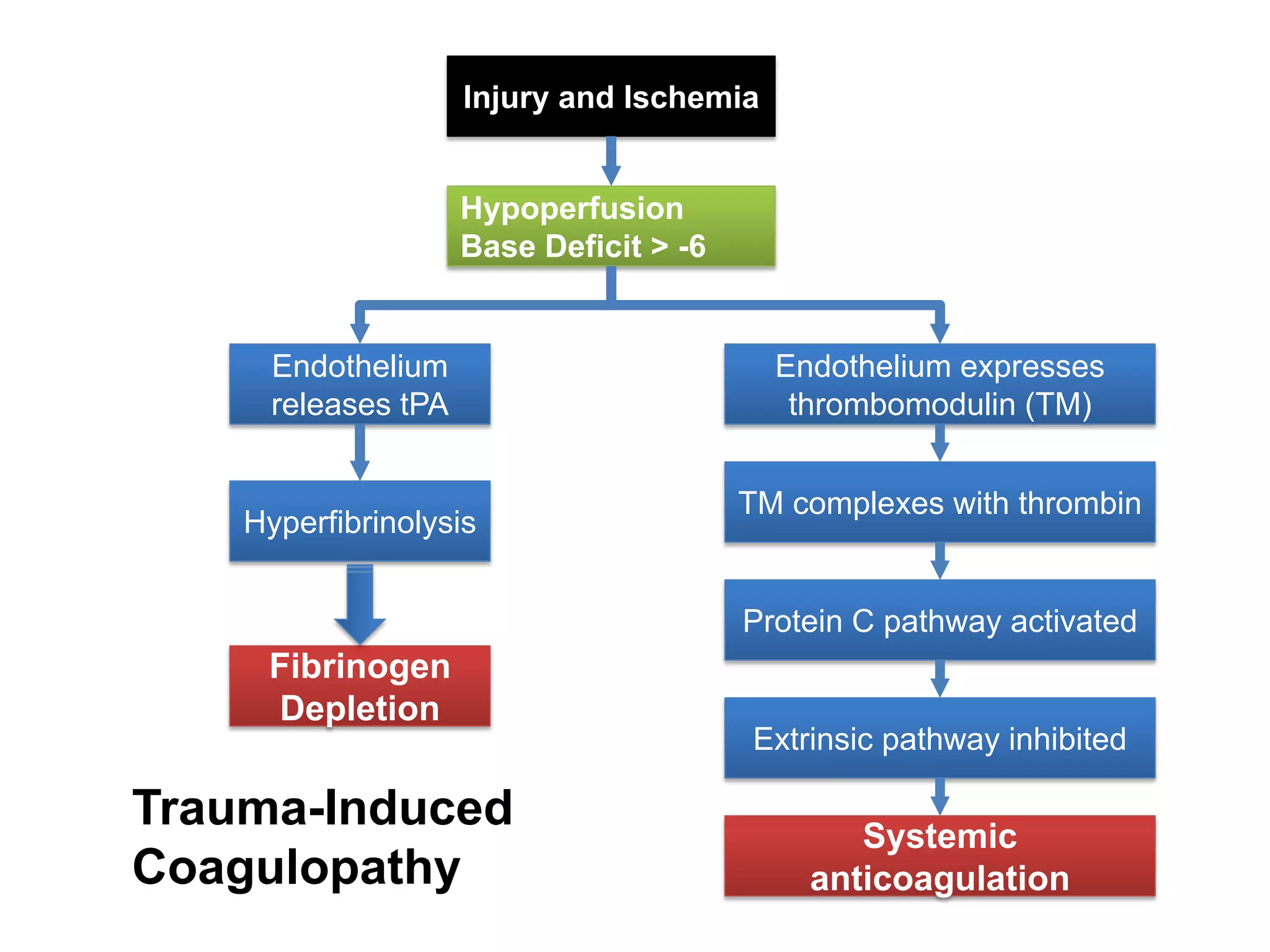

Damage control resuscitation (DCR) is a strategy aimed at addressing hemorrhage and its exacerbating factors in trauma patients, focusing on aggressive correction of coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis. It involves key concepts like permissive hypotension, the use of blood products for volume replacement, and a specific protocol for surgical interventions. DCR emphasizes early intervention both in the emergency room and during later surgical procedures to improve survival outcomes for severely injured patients.