La cinética química estudia la velocidad de las reacciones químicas, centrándose en la tasa de consumo de reactivos y formación de productos, así como la influencia de condiciones de reacción. Se define la tasa de reacción como el cambio en la concentración de reactivos o productos por unidad de tiempo, y se utiliza la ley de la velocidad para relacionar estas tasas con las concentraciones de reactivos. Se determina el orden de reacción a partir de datos experimentales y puede aceptarse un orden fraccional en algunos casos.

![Reaction Rate

• The concentrations of NO2 and

O2 increase with time, whereas

that of N2O5 decreases. The

reaction rate is defined as

−[N2O5]

𝑡

=

NO2

2𝑡

=

[O2]

1

2

𝑡](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-3-2048.jpg)

![Expressing the Reaction Rate

• Reaction rate is measured in terms of the changes in

concentrations of reactants or products per unit time.

• For the general reaction aA +bB → cC + dD, where A,

B, C, and D represent substances in the gas phase (g)

or in aqueous solution (aq), and a, b, c, d are their

coefficients in the balanced equation

• We measure the concentration of A at t1 and at t2:

The negative sign is used because the concentration of A

is decreasing. This gives the rate a positive value.

Rate =

change in concentration of A

change in time

[A2]- [A1]

t2 - t1

= - =

−[𝐴]

𝑎𝑡

=

− B

𝑏𝑡

=

[𝐶]

𝑐𝑡

=

[𝐷]

𝑑𝑡](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-4-2048.jpg)

![Rate Expression and Rate Constant

• For the decomposition of N2O5:

Rate = = k[N2O5],

• This equation is referred to as the rate expression for the

decomposition of N2O5.

• It tells how the rate of the reaction N2O5 (g) → 2NO2(g) +

1

2

O2(g) depends

on the concentration of reactant.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-8-2048.jpg)

![Order of Reaction

• For any general reaction occurring at a fixed temperature

aA + bB → cC + dD

• The rate expression has the general form

Rate = k[A]m[B]n

• The power (exponents m and n ) to which the concentration of

reactant is raised in the rate expression is called the order of

reaction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-11-2048.jpg)

![Order of Reaction

• A reaction has an individual order “with respect to” or “in” each

reactant.

• For the simple reaction A → products:

Rate = k[A]m

• If m is 0, the reaction is said to have zeroth order (Rate independent

of concentration). If m = 1, the reaction is first-order; if m = 2, it is

second-order](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-13-2048.jpg)

![Order of Reaction

• For the reaction aA + bB → cC + dD, Rate = k[A]m[B]n

• If the rate doubles when [A] doubles, the rate depends on [A]1 and

the reaction is first order with respect to A.

• If the rate quadruples when [A] doubles, the rate depends on [A]2

and the reaction is second order with respect to [A].

• If the rate does not change when [A] doubles, the rate does not

depend on [A], and the reaction is zero order with respect to A.

• Reaction order enables us to understand how the reaction depends

on reactant concentrations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-14-2048.jpg)

![Plots of reactant concentration, [A], vs. time for first-, second-,

and zero-order reactions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-16-2048.jpg)

![Plots of rate vs. reactant concentration, [A], for first-, second-,

and zero-order reactions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-17-2048.jpg)

![Individual and Overall Reaction Orders

For the reaction 2NO(g) + 2H2(g) → N2(g) + 2H2O(g):

The rate law is, rate = k[NO]2[H2]

The reaction is second order with respect to NO, first

order with respect to H2 and third order overall.

Note that the reaction is first order with respect to H2

even though the coefficient for H2 in the balanced

equation is 2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-18-2048.jpg)

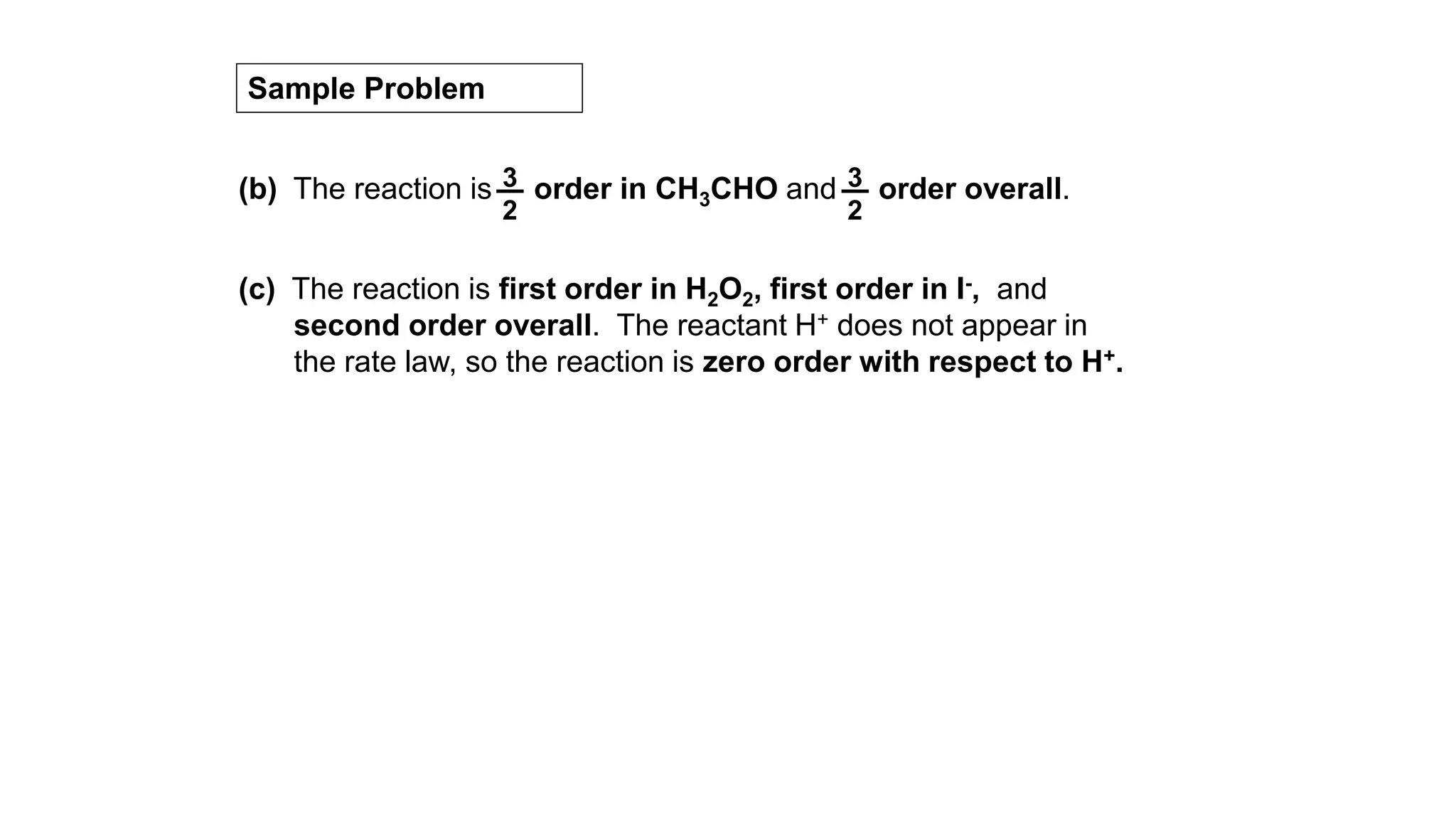

![Sample Problem

SOLUTION:

Determining Reaction Orders from Rate

Laws

PLAN: We inspect the exponents in the rate law, not the coefficients

of the balanced equation, to find the individual orders. We add

the individual orders to get the overall reaction order.

(a) The exponent of [NO] is 2 and the exponent of [O2] is 1, so the

reaction is second order with respect to NO, first order

with respect to O2 and third order overall.

PROBLEM: For each of the following reactions, use the given rate law

to determine the reaction order with respect to each

reactant and the overall order.

(a) 2NO(g) + O2(g) → 2NO2(g); rate = k[NO]2[O2]

(b) CH3CHO(g) → CH4(g) + CO(g); rate = k[CH3CHO]3/2

(c) H2O2(aq) + 3I-(aq) + 2H+(aq) →I3

-(aq) + 2H2O(l); rate = k[H2O2][I-]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-19-2048.jpg)

![Determination of the rate law

• 1. Isolation method

• Isolate each one of the reactants in turn by having all the others in large

excess. i.e if B is in excess and the rate law is = k[A][B]2

• Approximate [B] by [B]o.

• = k[A][B]2 where k = k [B]o.

• Pseudo first order, k = effective rate constant for a given fixed

concentration of B.

• If A is in excess the = k[B]2 with k = k[A]0 pseudosecond order rate

law](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-21-2048.jpg)

![Determining Reaction Orders

• For the general reaction A + 2B → C + D, the rate law will have the form:

Rate = k[A]m[B]n

• To determine the values of m and n, we run a series of experiments in which

one reactant concentration changes while the other is kept constant, and we

measure the effect on the initial rate in each case.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-22-2048.jpg)

![Initial Rates for the Reaction between A and B

Experiment

Initial Rate

(mol/L·s)

Initial [A]

(mol/L)

Initial [B]

(mol/L)

1 1.75x10-3 2.50x10-2 3.00x10-2

2 3.50x10-3 5.00x10-2 3.00x10-2

3 3.50x10-3 2.50x10-2 6.00x10-2

4 7.00x10-3 5.00x10-2 6.00x10-2

[B] is kept constant for experiments 1 and 2, while [A] is doubled.

Then [A] is kept constant while [B] is doubled.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-23-2048.jpg)

![Rate 2

Rate 1

=

k[A] [B]

k[A] [B]

m

2

n

2

m

1

n

1

Finding m, the order with respect to A:

We compare experiments 1 and 2, where [B] is kept

constant but [A] doubles:

=

[A]

[A]

m

2

m

1

=

[A]2

[A]1

m

3.50x10-3 mol/L·s

1.75x10-3mol/L·s

=

5.00x10-2 mol/L

2.50x10-2 mol/L

m

Dividing, we get 2.00 = (2.00)m so m = 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-24-2048.jpg)

![Rate 3

Rate 1

=

k[A] [B]

k[A] [B]

m

3

n

3

m

1

n

1

Finding n, the order with respect to B:

We compare experiments 3 and 1, where [A] is kept

constant but [B] doubles:

=

[B]

[B]

n

3

n

1

=

[B]3

[B]1

n

3.50x10-3 mol/L·s

1.75x10-3mol/L·s

=

6.00x10-2 mol/L

3.00x10-2 mol/L

m

Dividing, we get 2.00 = (2.00)n so n = 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-25-2048.jpg)

![Initial Rates for the Reaction between O2 and NO

Initial Reactant

Concentrations (mol/L)

Experiment

Initial Rate

(mol/L·s) [O2] [NO]

1 3.21x10-3 1.10x10-2 1.30x10-2

2 6.40x10-3 2.20x10-2 1.30x10-2

3 12.48x10-3 1.10x10-2 2.60x10-2

4 9.60x10-3 3.30x10-2 1.30x10-2

5 28.8x10-3 1.10x10-2 3.90x10-2

O2(g) + 2NO(g) → 2NO2(g) Rate = k[O2]m[NO]n](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-26-2048.jpg)

![Rate 2

Rate 1

=

k[O2] [NO]

k[O2] [NO]

m

2

n

2

m

1

n

1

Finding m, the order with respect to O2:

We compare experiments 1 and 2, where [NO] is kept

constant but [O2] doubles:

=

[O2]

[O2]

m

2

m

1

=

[O2]2

[O2]1

m

6.40x10-3 mol/L·s

3.21x10-3mol/L·s

=

2.20x10-2 mol/L

1.10x10-2 mol/L

m

Dividing, we get 1.99 = (2.00)m or 2 = 2m, so m = 1

The reaction is first order with respect to O2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-27-2048.jpg)

![Finding n, the order with respect to NO:

We compare experiments 1 and 3, where [O2] is kept

constant but [NO] doubles:

Rate 3

Rate 1

=

[NO]3

[NO]1

n

12.8x10-3 mol/L·s

3.21x10-3mol/L·s

=

2.60x10-2 mol/L

1.30x10-2 mol/L

n

Dividing, we get 3.99 = (2.00)n or 4 = 2n, so n = 2.

The reaction is second order with respect to NO.

log a

log b

n =

log 3.99

log 2.00

= = 2.00

Alternatively:

The rate law is given by: rate = k[O2][NO]2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-29-2048.jpg)

![Determining Reaction Orders from Rate Data

PROBLEM: Many gaseous reactions occur in a car engine and exhaust

system. One of these is

NO2(g) + CO(g) → NO(g) + CO2(g) rate = k[NO2]m[CO]n

Use the following data to determine the individual and

overall reaction orders:

Experiment

Initial Rate

(mol/L·s)

Initial [NO2]

(mol/L)

Initial [CO]

(mol/L)

1 0.0050 0.10 0.10

2 0.080 0.40 0.10

3 0.0050 0.10 0.20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-30-2048.jpg)

![PLAN: We need to solve the general rate law for m and for n and

then add those orders to get the overall order. We proceed by

taking the ratio of the rate laws for two experiments in which

only the reactant in question changes concentration.

SOLUTION:

rate 2

rate 1

[NO2] 2

[NO2] 1

m

=

k [NO2]m

2[CO]n

2

k [NO2]m

1 [CO]n

1

=

0.080

0.0050

0.40

0.10

=

m

16 = (4.0)m so m = 2

To calculate m, the order with respect to NO2, we compare

experiments 1 and 2:

The reaction is second order in NO2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-31-2048.jpg)

![k [NO2]m

3[CO]n

3

k [NO2]m

1 [CO]n

1

[CO] 3

[CO] 1

n

=

rate 3

rate 1

=

0.0050

0.0050

=

0.20

0.10

n

1.0 = (2.0)n so n = 0

rate = k[NO2]2[CO]0 or rate = k[NO2]2

To calculate n, the order with respect to CO, we compare experiments

1 and 3:

The reaction is zero order in CO.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-32-2048.jpg)

![SOLUTION:

(a) For reactant A (red):

Experiments 1 and 2 have the same number of particles of B, but

the number of particles of A doubles. The rate doubles. Thus the

order with respect to A is 1.

(b) Rate = k[A][B]2

(c) Between experiments 3 and 4, the number of particles of A

doubles while the number of particles of B does not change. The

rate should double, so rate = 2 x 2.0x10-4 = 4.0x10-4mol/L·s

For reactant B (blue):

Experiments 1 and 3 show that when the number of particles of B

doubles (while A remains constant), the rate quadruples. The

order with respect to B is 2.

The overall order is 1 + 2 = 3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-34-2048.jpg)

![Information sequence to determine the kinetic parameters of

a reaction.

Series of plots of

concentration vs.

time

Initial rates

Reaction

orders

Rate constant (k)

and actual rate law

Determine slope of tangent at t0 for

each plot.

Compare initial rates when [A] changes and

[B] is held constant (and vice versa).

Substitute initial rates, orders, and

concentrations into rate = k[A]m[B]n, and

solve for k.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-36-2048.jpg)

![Reactant Concentration and time

• The rate expression Rate = = k[N2O5], shows how the rate of decomposition of

N2O5 changes with concentration.

• However, it is more important to know the relation between

concentration and time rather than between concentration and rate.

• you would want to know how much N2O5 is left after 5 minutes, 1 hour, or

several days

• The above equation does not provide this information.

• Using calculus, it is possible to develop integrated rate equations relating reactant

concentration to time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-37-2048.jpg)

![First-Order Reactions

Integrated rate equations for a general

reaction A→ products

rate = −

[𝐴]

𝑡

From the rate law

rate = k[A]

Combining the two equations

rate = −

[𝐴]

𝑡

= k[A]

In differential form the eqn becomes

−

𝑑[𝐴]

𝑑𝑡

= k[A]

Rearranging

−

𝑑[𝐴]

[A]

= 𝑘𝑑𝑡

Integrating btwn 𝑡 = 0 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑡 = 𝑡

t = 0 can be any time when we choose

to start monitoring the change in the

concentration of A.

න

[𝐴]0

[𝐴]𝑡

𝑑[𝐴]

[A]

= −𝑘 න

0

𝑡

𝑑𝑡

− ln 𝐴 𝑡 − 𝑙𝑛 𝐴 0 = 𝑘𝑡

ln 𝐴 𝑡 = 𝑙𝑛 𝐴 0 − kt … 1

𝐴 𝑡 = [𝐴]0𝑒−𝑘𝑡 … (2)

(1) is of the form y = mx + b, linear eqn

(2) is used for predicting concentration

of A at any time after the reaction has

started](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-38-2048.jpg)

![Relationship between reactant concentration and

time

• As we would expect during the

course of a reaction, the

concentration of the reactant A

decreases with time

• If we plot of In[A]t against t and

get a straight line then the

reaction is first order. Slope is

equal to −𝑘 and a y intercept

equal to 𝑙𝑛 𝐴 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-39-2048.jpg)

![Exercise: The concentration of N2O5 in liquid bromine varied with

time as follows:

t/s 0 200 400 600 1000

[N2O5]/M 0.110 0.073 0.048 0.032 0.014

Determine the order and rate constant

Order = 1 (first order)

Rate constant = 2.1 x 10-3s-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-40-2048.jpg)

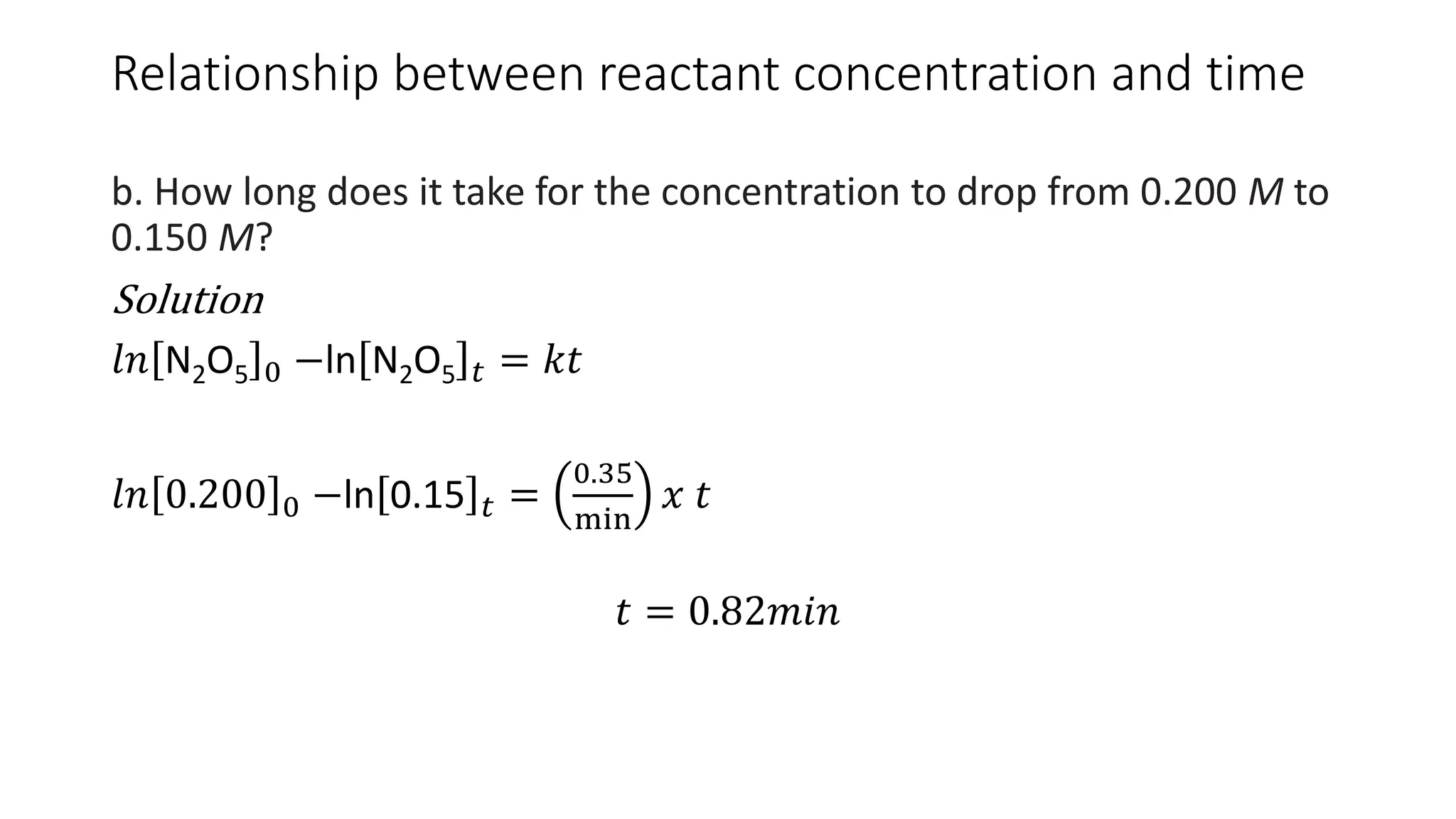

![Relationship between reactant concentration and time

Example

Consider the first-order decomposition of N2O5 67°C, where k = 0.35/min.

a. What is the concentration after six minutes, starting at 0.200 M?

Solution

𝑙𝑛 N2O5 0 −ln N2O5 𝑡 = 𝑘𝑡

N2O5 𝑡 = [N2O5]0𝑒−𝑘𝑡

= 0.200𝑥𝑒−(0.35𝑥6)

= 0.024𝑚𝑜𝑙/𝐿](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-41-2048.jpg)

![Graphical method for finding the reaction order from the

integrated rate law.

First-order reaction

ln [A]0

[A]t

= - kt

integrated rate law

ln[A]t = -kt + ln[A]0

straight-line form

A plot of ln [A] vs. time gives a straight line for a first-order reaction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-47-2048.jpg)

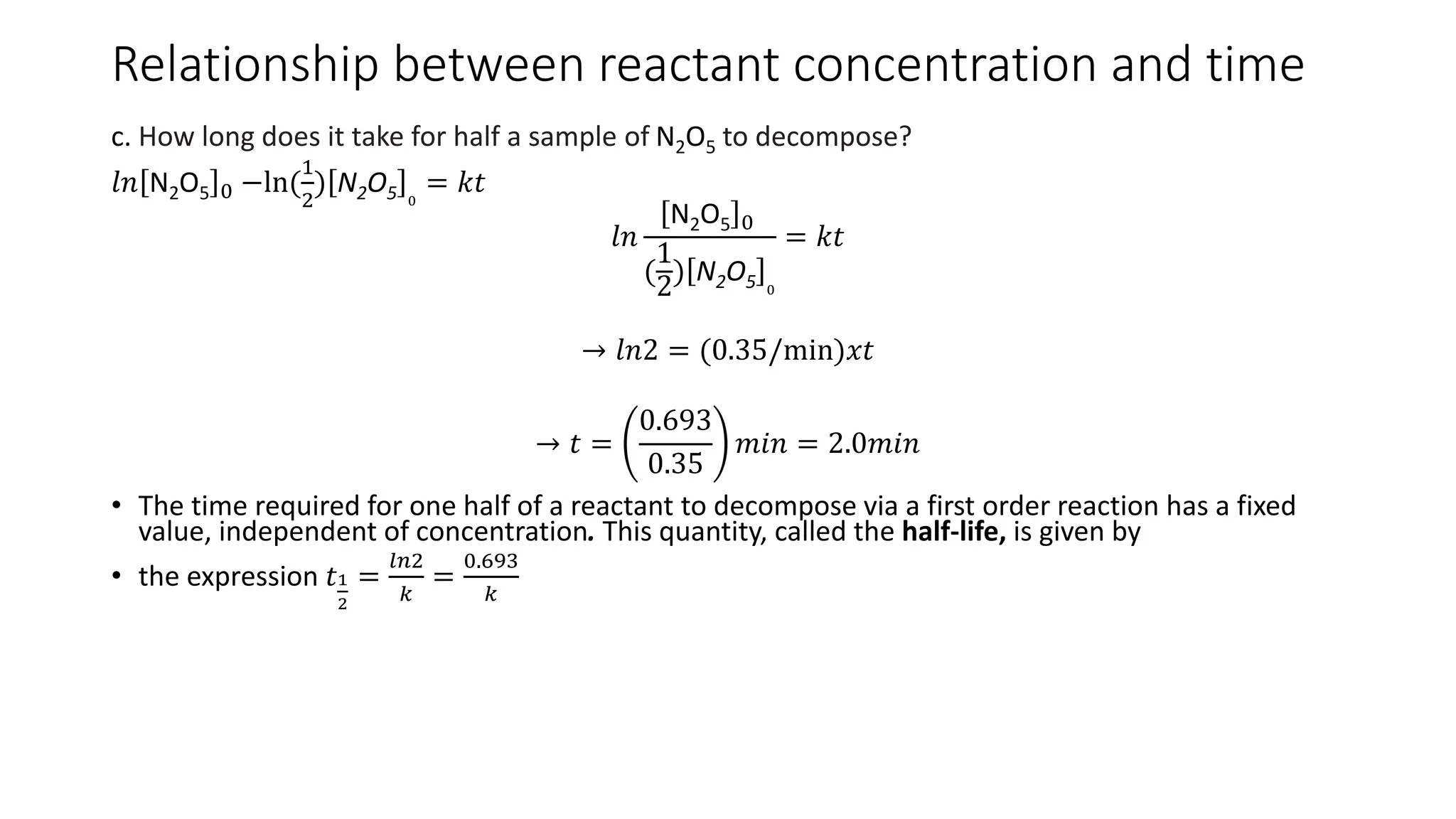

![Half-life method

• Time taken for concentration of reactant to fall to ½ its initial value.

• It’s a guide to the order of a reaction for it depends on initial concentration for

reactions of different orders.

For first order: ln 𝐴 𝑡 = 𝑙𝑛 𝐴 0 − kt

𝑙𝑛 A 0 − ln

1

2

A 0

= 𝑘𝑡1

2

𝑘𝑡 = ln

[𝐴]0

1

2

[𝐴]0

𝑡 1/2 =

𝑙𝑛2

𝑘

=

0.693

𝑘

t1/2: rapid method of measuring 1st order reaction rate

t1/2 for first order reaction is independent of the initial concentration of the

reactant.

will be constant. Not true for second order rxn.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-48-2048.jpg)

![Second-order reaction

• A second-order reaction is a reaction whose rate depends on the concentration

of one reactant raised to the second power or on the concentrations of two

different reactants, each raised to the first power.

• Consider the reaction: A→ products

rate −

𝐴

𝑡

= 𝑘[𝐴]2

• For the reaction A + B→ products:

rate = k A B

• The reaction is first order in A and first order in B, so it has an overall reaction

order of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-50-2048.jpg)

![Second-order reaction

• Integrated rate equations for a general reaction A→ products

𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 = −

𝐴

𝑡

න

[𝐴]0

[𝐴]𝑡

𝑑[𝐴]

[A]2

= −𝑘 න

0

𝑡

𝑑𝑡

න 𝑥𝑛

𝑑𝑥 =

𝑥𝑛+1

𝑛 + 1

+ 𝐶

1

𝐴 𝑡

=

1

𝐴 0

+ 𝑘𝑡 … 1

𝐴 𝑡 =

𝐴 0

1 + 𝑘𝑡 𝐴 0

… 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-51-2048.jpg)

![Graphical method for finding the reaction order from the

integrated rate law.

Second-order reaction

integrated rate law

1

[A]t

1

[A]0

- = kt

straight-line form

1

[A]t

1

[A]0

= kt +

A plot of vs. time gives a straight line for a second-order reaction.

1

[A]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-56-2048.jpg)

![Zero-Order Reactions

• First- and second-order reactions are the most common reaction

types. Reactions whose order is zero are rare. For a zero-order

reaction.

A→ products: 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 = 𝑘[𝐴]0 = 𝑘

න

[𝐴]0

[𝐴]𝑡

𝑑[𝐴] = −𝑘 න

0

𝑡

𝑑𝑡

[𝐴]𝑡 = −𝑘𝑡 + [𝐴]0

• A plot of [𝐴]𝑡versus t gives a straight line with slope = -k and y

intercept = [𝐴]0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-58-2048.jpg)

![Zero-Order Reactions

• The half-life of a zero-order reaction we set [𝐴]𝑡 =

[𝐴]0

2

𝑡1/2 =

𝐴 0

2𝑘

• Most of the zero-order reactions take place at solid surfaces, where

the rate is independent of concentration in the gas phase.

• A typical example is the thermal decomposition of hydrogen iodide on gold:

• When the gold surface is completely covered with HI molecules,

increasing the concentration of HI(g) has no effect on reaction rate.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-59-2048.jpg)

![Graphical method for finding the reaction order from the

integrated rate law.

Zero-order reaction

A plot of [A] vs. time gives a straight line for a first-order reaction.

integrated rate law

[A]t - [A]0 = - kt

straight-line form

[A]t = - kt + [A]0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-60-2048.jpg)

![1/[HI] vs time gives a linear plot. The reaction

is second-order.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-62-2048.jpg)

![Graphical determination of the reaction order for the decomposition of

N2O5.

The concentration data is used to

construct three different plots. Since the

plot of ln [N2O5] vs. time gives a straight

line, the reaction is first order.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-63-2048.jpg)

![Reactions approaching equilibrium

• At equilibrium, the reverse rate matches the forward rate and the reactants and products are

present in abundances given by the equilibrium constant for the reaction.

• When the reaction has reached equilibrium the concentrations of A and B are [A]eq and [B]eq and

there is no net formation of either substance. It follows that k1[A]eq = k-1[B]eq and therefore that

the equilibrium constant for the reaction is related to the rate constants by

• 𝐾 =

[𝐵]𝑒𝑞

[𝐴]𝑒𝑞

=

𝑘1

𝑘−1

• If the forward rate constant is much larger than the reverse rate constant, then K >> 1. If the

opposite is true, then K << 1. This result is a crucial connection between the kinetics of a reaction

and its equilibrium properties.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-65-2048.jpg)

![Figure 16.14 Increase of the rate constant with temperature for

the hydrolysis of an ester.

Expt [Ester] [H2O] T (K) Rate

(mol/L·s)

k

(L/mol·s)

1 0.100 0.200 288 1.04x10-3 0.0521

2 0.100 0.200 298 2.20x10-3 0101

3 0.100 0.200 308 3.68x10-3 0.184

4 0.100 0.200 318 6.64x10-3 0.332

Reaction rate and k increase exponentially as T increases.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkineticsratelawsandreactionmechanisms-240318015538-a317edc4/75/Chemical-kinetics_Rate-laws-and-reaction-mechanisms-pdf-67-2048.jpg)