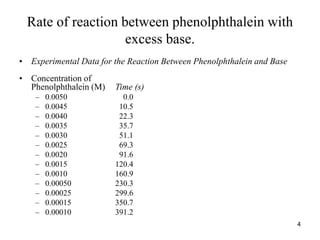

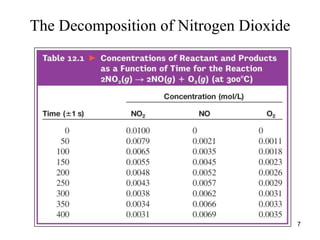

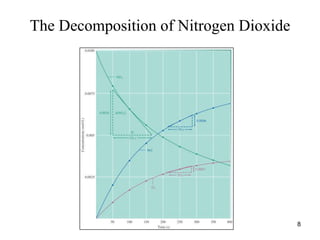

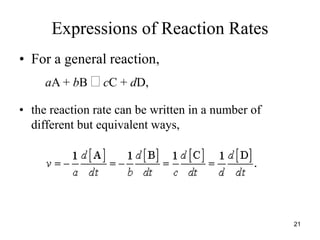

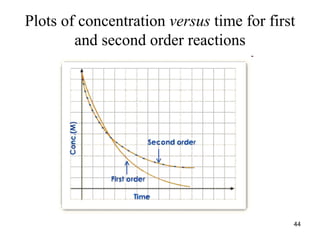

The document covers key concepts in chemical kinetics, including the expression of reaction rates, determination of reaction orders, and the methods used to derive rate laws. It outlines various types of rates (initial, instantaneous, and average) and emphasizes the importance of rate laws in understanding reaction mechanisms at a molecular level. Additionally, it details the graphical methods for determining rate laws and explores the half-lives of reactions and the relationship between concentration and reaction rates.

![Instantaneous Rate:

Rate of decrease in [Phenolphthalein]

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-5-320.jpg)

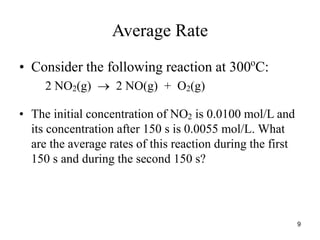

![Average rate during the first 150 s

• Solution:

• Average rate =

• =

• =

• = 3.0 x 10-5

mol/(L.s)

t

]

[NO

- 2

s

150

mol/L)

0.0100

-

mol/L

(0.0055

-

s

150

mol/L

0.0045

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-10-320.jpg)

![Average rate during the second 150 s

• Solution:

• Average rate =

• =

• =

• = 1.1 x 10-5

mol/(L.s)

• Average rate decreases as reaction progresses

because the reactant concentration has decreased

t

]

[NO

- 2

s

150

mol/L)

0.0055

-

mol/L

(0.0038

-

s

150

mol/L

0.0017

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-11-320.jpg)

![Rate Law

• Shows how the rate depends on the

concentrations of reactants.

• For the decomposition of nitrogen dioxide:

2NO2(g) → 2NO(g) + O2(g)

Rate = k[NO2]n:

k = rate constant

n = order of the reactant

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-12-320.jpg)

![Rate Law

Rate = k[NO2]n

• The concentrations of the products do not

appear in the rate law because the reaction

rate is being studied under conditions where

the reverse reaction does not contribute to the

overall rate.

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-13-320.jpg)

![Rate Law

Rate = k[NO2]n

• The value of the exponent n must be

determined by experiment; it cannot be

written from the balanced equation.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-14-320.jpg)

![Rate Law

• An expression or equation that relates the rate

of reaction to the concentrations of reactants at

constant temperature.

• For the reaction:

R1 + R2 + R3 Products

Rate = k[R1]x

[R2]y

[R3]z

Where k = rate constant; x, y, and z are the rate orders

with respect to individual reactants. Rate orders are

determined experimentally.

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-15-320.jpg)

![Expressions of Reaction Rates and Their

Stoichiometric Relationships

• Consider the reaction:

2N2O5 4NO2 + O2

• Rate of disappearance of N2O5 =

• Rate of formation of NO2 =

• Rate of formation of O2 =

• Stoichiometric relationships of these rates

•

t

]

NO

[ 2

t

]

[O2

t

]

O

[N 5

2

t

]

[O

)

t

]

NO

[

(

4

1

)

t

]

O

[N

(

2

1 2

2

5

2

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-20-320.jpg)

![Rate Laws

• For a general reaction,

aA + bB + eE Products

• The rate law for this reaction takes the form:

• where k is called the "rate constant."

• x, y, and z, are small whole numbers or simple

fractions and they are the rate order with respect to

[A], [B], and [E]. The sum of x + y + z + . . . is called

the “overall order" of the reaction.

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-22-320.jpg)

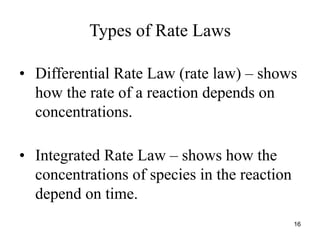

![Types of Rate Laws

• Consider a general reaction:

aA + bB Products

• The rate law is expressed as,

Rate = k[A]x

[B]y

,

Where the exponents x and y are called the rate

order of the reaction w.r.t. the respective reactants;

These exponents are usually small integers or simple

fractions.

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-23-320.jpg)

![Types of Rate Laws

1. Zero-Order Reactions

1. In a zero order reaction the rate does not depend

on the concentration of reactant,

2. For example, the decomposition of HI(g) on a

gold catalyst is a zero-order reaction;

3. 2 HI(g) H2(g) + I2(g)

4. Rate = k[HI]0

= k;

(The rate is independent on the concentration of HI)

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-24-320.jpg)

![Types of Rate Laws

• First Order Reactions

In a first order reaction the rate is proportional to

the concentration of one of the reactants.

Example, for first-order reaction:

2N2O5(g) 4NO2(g) + O2(g)

• Rate = k[N2O5],

The rate of decomposition of N2O5 is proportional

to [N2O5], the molar concentration of N2O5

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-25-320.jpg)

![Types of Rate Laws

• Second Order Reactions

In a second order reaction, the rate is proportional

to the second power of the concentration of one of

the reactants.

Example, for the decomposition of NO2 follows

second order w.r.t. [NO2]

2NO2(g) 2NO(g) + O2(g)

• Rate = k[NO2]2

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-26-320.jpg)

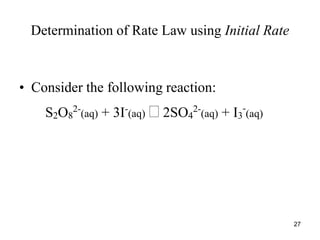

![Determination of Rate Law using Initial Rate

Reaction: S2O8

2-

(aq) + 3I-

(aq) 2SO4

2-

(aq) + I3

-

(aq)

• The following data were obtain.

•

• Expt. [S2O8

2-

] [I-

] Initial Rate,

• # (mol/L) (mol/L) (mol/L.s)

•

• 1 0.036 0.060 1.5 x 10-5

• 2 0.072 0.060 2.9 x 10-5

• 3 0.036 0.120 2.9 x 10-5

•

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-28-320.jpg)

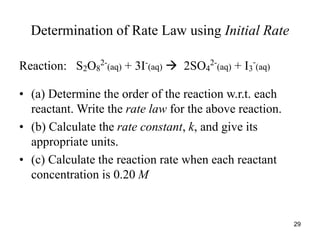

![Determination of Rate Law using Initial Rate

• Solution: The rate law = Rate = k[S2O8

2-

]x

[I-

]y

,

here x and y are rate orders.

• (a) Calculation of rate order, x:

•

1

2

2

~

mol/L.s

10

x

1.5

mol/L.s

10

x

2.9

2

)

060

.

0

(

)

036

.

0

(

)

060

.

0

(

)

072

.

0

(

]

[I

]

O

[S

]

I

[

]

O

[S

5

-

5

-

1

-

1

-

2

8

2

3

-

2

-

2

8

2

y

M

M

k

M

M

k

k

k

x

x

y

x

y

x

y

x

y

x

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-30-320.jpg)

![Determination of Rate Law using Initial Rate

• (b) Calculation of rate order, y:

•

• This reaction is first order w.r.t. [S2O8

2-

] and [I-

]

• Rate = k[S2O8

2-

][I-

]

1

2

2

~

mol/L.s

10

x

1.5

mol/L.s

10

x

2.9

2

)

060

.

0

(

)

036

.

0

(

)

120

.

0

(

)

036

.

0

(

]

[I

]

O

[S

]

I

[

]

O

[S

5

-

5

-

1

-

-

2

8

2

3

-

-

2

8

2

y

M

M

k

M

M

k

k

k

y

y

y

x

y

x

y

x

y

x

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-31-320.jpg)

![Calculating rate constant and rate at different

concentrations of reactants

• Rate constant, k =

• = 6.6 x 10-3

L.mol-1

.s-1

• If [S2O8

2-

] = 0.20 M, [I-

] = 0.20 M, and

– k = 6.6 x 10-3

L.mol-1

.s-1

• Rate = (6.6 x 10-3

L.mol-1

.s-1

)(0.20 mol/L)2

• = 2.6 x 10-4

mol/(L.s)

mol/L)

60

mol/L)(0.0

(0.038

mol/L

10

x

1.5 -5

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-32-320.jpg)

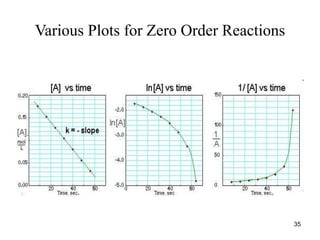

![Integrated Rate Law

• Graphical method to derive the rate law

of a reaction:

• Consider a reaction with single reactant:

• R Products

• If the reaction is zero-order w.r.t. [R],

• Then,

k

Rate

t

[R]

-

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-33-320.jpg)

![Graphical Method for Zero-Order Reaction

k

Rate

t

[R]

-

[R] = -kt, and [R]t = [R]0 = kt;

A plot of [R]t versus t yields a straight

line with k = -slope.

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-34-320.jpg)

![Graph of Zero-order Reactions

• Plot of [R]t versus t:

[R]t

t

slope = -k

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-36-320.jpg)

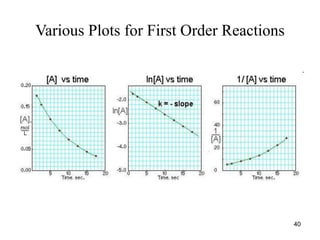

![Graphical Method for First Order Reactions

• If the reaction: R Products is a first order

reaction, then

• Which yields:

• And a plot of ln[R]t versus t will yield a straight line

with slope = -k and y-intercept = ln[R]0

[R]

t

[R]

-

k

Rate

t

-

ln[R]

ln[R]

t;

-

[R]

[R]

0

t k

k

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-37-320.jpg)

![Graph of First Order Reactions

Plot of ln]R]t versus t:

ln[R]t

t

slope = -k

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-38-320.jpg)

![Plots of [A] and ln[A] versus time for First Order

Reactions

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-39-320.jpg)

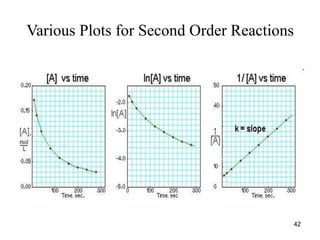

![Graphical Method for Second Order Reactions

• If the reaction: R Products follows second-

order kinetics, then

• or

•

• and

• A plot of 1/[R]t versus t will yield a straight line

with slope = k and y-intercept = 1/[R]0

2

[R]

t

[R]

-

k

Rate

t

[R]

[R]

2

k

[R]

1

t

[R]

1

0

t

k

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-41-320.jpg)

![Graph of Second-order Reactions

• Plot of 1/[R]t versus time:

t

R]

[

1

time

slope = k

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-43-320.jpg)

![Plots of ln[Concentration] versus time

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-45-320.jpg)

![Plots of 1/[Concn.] versus time

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-46-320.jpg)

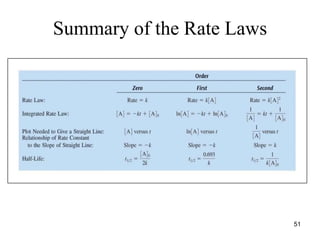

![Characteristics of plots for zero, first, and second

order reactions

• The graph that is linear indicates the order of the

reaction with respect to A (reactant):

• For a zero order reaction, Rate = k (k = - slope)

• For a 1st order reaction, Rate = k[A] (k = - slope)

• For a 2nd order reaction, Rate = k[A]2

(k = slope)

• For zero-order reaction, half-life, t1/2 = [R]0/2k;

• For first order reaction, half-life, t1/2 = 0.693/k;

• For second order reaction, half-life, t1/2 = 1/k[R]0;

47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-47-320.jpg)

![Half-Lives of Reactions

• For zero-order reaction: t1/2 = [R]0/2k;

• For first-order reaction: t1/2 = 0.693/k;

• For second-order reaction: t1/2 = 1/(k[R]0)

• Note: For first-order reaction, the half-life is

independent of the concentration of reactant, but for

zero-order and second-order reactions, the half-lives

are dependent on the initial concentrations of the

reactants.

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-48-320.jpg)

![Exercise

Consider the reaction aA Products.

[A]0 = 5.0 M and k = 1.0 x 10–2 (assume the

units are appropriate for each case). Calculate

[A] after 30.0 seconds have passed, assuming

the reaction is:

a) Zero order

b) First order

c) Second order

4.7 M

3.7 M

2.0 M

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-52-320.jpg)

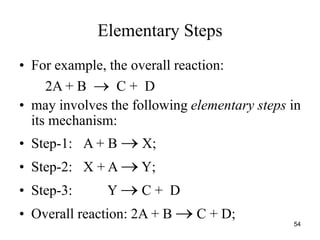

![Molecularity in Elementary Steps

• Molecularity in the number of molecular species that react in

an elementary process.

• Rate Law for Elementary Processes:

• Elementary Reactions Molecularity Rate Law

•

• A product Unimolecular Rate = k[A]

• 2A product Bimolecular Rate = k[A]2

• A + B product Bimolecular Rate = k[A][B]

• 2A + B product Termolecular Rate = k[A]2

[B]

•

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-55-320.jpg)

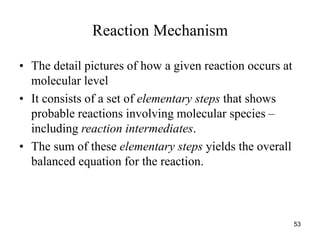

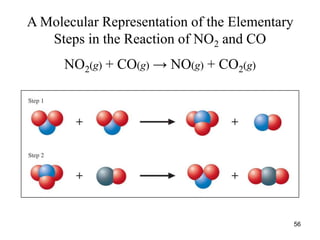

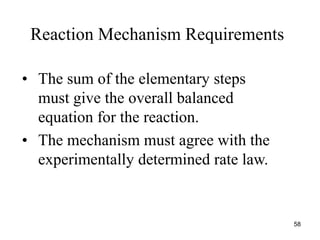

![Reaction Mechanism

• Step-1: NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO

• Step-2: NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2

• Overall: NO2 + CO NO + CO2

• The experimental rate law is Rate = k[NO2]2

• Which implies that the above reaction is second-order

w.r.t. NO2 , but is zero-order in [CO].

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-57-320.jpg)

![Dependence of Rate on Concentration

• This is contained in the rate law – that is, for

reaction:

aA + bB + cC Products

Rate = k[A]x

[B]y

[C]z

;

67](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-1a-240613235737-4e3353ea/85/Chemical-kinetics-and-reaction-lecture-notes-67-320.jpg)