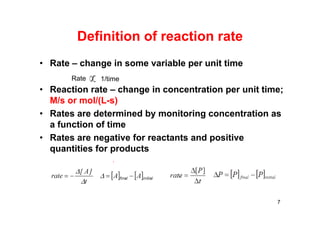

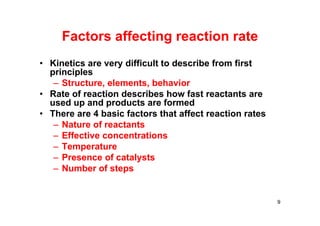

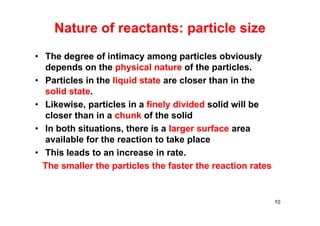

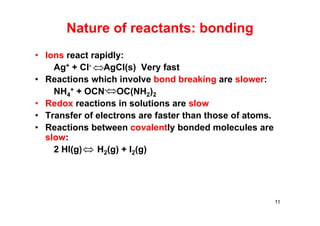

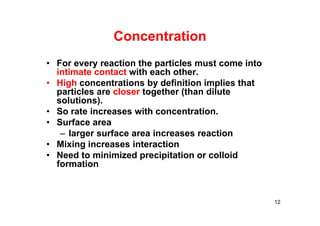

This document discusses chemical kinetics and reaction rates. It begins with an introduction to chemical kinetics and defines reaction rate. It then discusses factors that affect reaction rates such as nature of reactants, concentration, temperature, and catalysts. It describes different types of reaction rates and how they are measured. The document also covers rate laws, determining rate orders experimentally, and integrated and differential rate equations for zero, first, and second order reactions. It concludes with an overview of rate theories including the Arrhenius equation.

![Types of reaction rate

• Instantaneous rate – rate at a specific time

• Average rate – ∆[A] over a specific time interval

• Initial rate – instantaneous rate at t = 0

• Note: Rates and rate laws are not based on

stoichiometry!! They must be determined

experimentally.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-8-320.jpg)

![• Rate has units of moles per liter per unit time

- M s-1, M h-1

• Consider the hypothetical reaction

aA + bB cC + dD

• We can write

Reaction rates and stoichiometry

14

t

D

dt

C

c

t

B

bt

A

a

r

][1][1

][1][1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-14-320.jpg)

![Rate law

• Consider the following reaction

aA + bB products

• Rate Law: equation describing the

relationship between the reaction rate and

concentration of a reactant or reactants

Rate = k[A]m[B]n

where k is called the rate constant

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-17-320.jpg)

![Concentration and rate

aA + bB → cC + dD

• General form of rate law:

rate = k[A]m[B]n

[A], [B] – concentration, in M or P

k – rate constant; units vary

m, n – reaction orders

• Reaction orders and, thus, rate laws must be

determined EXPERIMENTALLY!!!

– Note: m ≠ a and n ≠ b

– Overall order = sum of individual orders

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-18-320.jpg)

![Reaction order

• Rate = k[A][B]0 m = 1 and n = 0

- reaction is first order in A and zero order in B

- overall order = 1 + 0 = 1

- usually written: Rate = k[A]

• The values of the reaction order must be determined

experimentally; they cannot be found by looking at

the equation, i.e., the stoichiometry of the reaction

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-19-320.jpg)

![Reaction orders

For the reaction: A →B, the rate law is:

rate = k[A]m

Order (m) ∆[A] by a factor of Rate increases by

Zero (0) 2, 4, 15, ½, etc. None

1st (1)

2 2X

3 3X

2nd (2)

2 4X

3 9X

½ ¼X

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-22-320.jpg)

![Example

1. What is the order with respect to NO?

2. What is the order with respect to H2?

3. What is the overall order?

4. If [NO] is doubled, what is the effect on the reaction

rate?

5. If [H2] is halved, what is the effect on the reaction

rate?

6. What are the units of k?

23

2

1

3

quadrupled

halved

M-2-s-2

2 NO(g) + 2 H2(g) → N2(g) + 2 H2O(g)

rate = k[NO]2[H2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-23-320.jpg)

![24

Rate = 9x10-3 (h-1) x 0.02 (M) = 1.8x10-5 (M-h-1)

d[Cl]/dt = rate = 1.8x10-5 (M-h-1)

What is the rate of Cl- production under

these conditions?

Calculate the rate of reaction when the

concentration of PtCl2(NH3)2 is 2.0x10-2 M.

PtCl2(NH3)2 + H2O PtCl(H2O)(NH3)2 + Cl-

Example](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-24-320.jpg)

![Calculate rate when [NO] = 0.025 M and [H2] = 0.015 M.

25

Rate = 6x10-4 (M-2-s-1)x0.025 M x 0.015 M

=225 (M-s-1)

2 NO(g) + 2 H2(g) → N2(g) + 2 H2O(g)

rate = k[NO]2[H2] k = 6.0 x 104 M-2s-1 @1000K

Example](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-25-320.jpg)

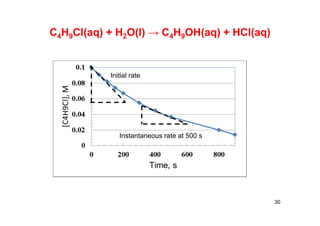

![In this reaction, the

concentration of butyl

chloride, C4H9Cl, is

measured at various

times.

C4H9Cl(aq) + H2O(l) → C4H9OH(aq) + HCl(aq)

28

Time, s [C4H9Cl], M

0 0.1000

50 0.0905

100 0.0820

150 0.0741

200 0.0671

300 0.0549

400 0.0448

500 0.0368

800 0.0200

10,000 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-28-320.jpg)

![29

Time, s [C4H9Cl], M Average rate, M/s

0 0.1000

50 0.0905 1.9E-4

100 0.0820 1.7E-4

150 0.0741 1.6E-4

200 0.0671 1.4E-4

300 0.0549 1.22E-4

400 0.0448 1.01E-4

500 0.0368 0.8E-4

800 0.0200 0.56E-4

10,000 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-29-320.jpg)

![First order

]A)[I,T(k

dt

]A[d

ν

R

A

1

t)I,T(k

o e]A[]A[

t

.

)I,T(k

]Alog[]Alog[ o

3032

1.0

0.1

0.01

0.001

1 2 3

t

Log [A]

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-40-320.jpg)

![Second order

2

A

]A)[T(k

dt

]A[d1

R

t)T(kν

]A[]A[

i

0

11

41

t)T(k]A[]B[

]A[

]B[

ln

]A[

]B[]A[

ln oAoB

o

oAoAoB

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-41-320.jpg)

![Third order

]C][B][A)[T(k

dt

]A[d1

R

A

1CBA

ooo ]C[]B[]A[

t)T(k2

]A[

1

]A[

1

2

o

2

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-42-320.jpg)

![Summary Rate Equations

43

Rate = k[A]n; [A] = concentration at time t, [Ao] = initial concentration, [X] =

product conc.

[A0]-[A] = kt, [X] = kt

ln[A0] - ln[A] = kt, ln[A0] - ln([Ao] - [X]) = kt

0 order k = M/s

1st order k = 1/s

2nd order

k = M-1-s-1

3rd order k = M-2-s-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-43-320.jpg)

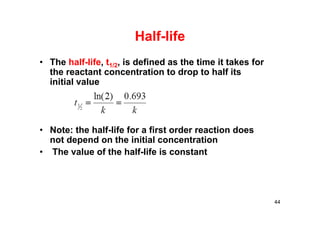

![Half-Life

45

• Half-life

– A =Aoe-t

– = ln2/t1/2

– If a rate half life is known,

fraction reacted or

remaining can be

calculated

(CH3)2N2(g) N2(g) + C2H6(g)

Time Pressure (torr)

0 36.2

30 46.5

Ct =Coe-kt

kt0.5=ln(2)

to.5 = - [ln(2) t]/[ln(Ct/Co)]

to.5 = - [ln(2) (30)]/[ln(25.9/36.5)]=62.1 (min)

t A B C

0 36.2 0 0

3036.2(1-x) 36.2x 36.2x

46.5 = 36.2(1-x+2x)=36.2(1+x)=36.2+36.2x

46.5-36.2 = 36.2x x = 0.285

A = 36.5(1-0.285) = 25.9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-45-320.jpg)

![ARRHENIUS’ EQUATION

49

E1

E2

E=Ea

Initial state

Final state

Activated state; X*

E1

E2

E=Ea

Initial state

Final state

Activated state; X*

DCBA kk

11

]][[]][[ 11 DCkBAk

]][[

]][[

1

1

BA

DC

k

k

Kc

11 EEE

2

11 lnln

RT

E

dt

kd

dt

kd

1

ln

2

11

RT

E

dt

kd

1

ln

2

11

RT

E

dt

kd

2

ln

RT

E

dT

kd a

C

RT

E

k a

ln C = constant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-49-320.jpg)

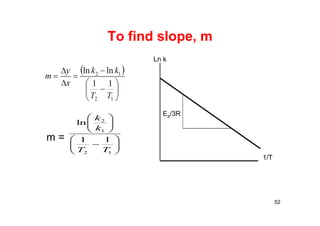

![Arrhenius’ Equation

• This is Arrhenius’ Equation

• Can be arranged in the form of a straight line

• ln k = (-Ea/R)(1/T) + ln A

• Plot ln k vs. 1/T slope = -Ea/R

1.0

0.1

0.01

0.001

1 2 3

1/T

Log [k]

EA/2.303

= dlog K/d(1/T)

Diffusion

regime

Reaction

regime

Ea < 5 kcal/mol: diffusion

control reaction

Ea > 5 kcal/mol; reactive

control

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-53-320.jpg)

![Collision Theory

RT

E

AAezv

22

AA ncd2

2

1

z

m

T

dn2

m

T8

nd2

2

1

z 2222

AA

RT

E

BA

BA2

ABBA e

mm

mm

T8dnnv

2

1

62

molecules/(cm3-s)

mπ

Tκ

c

8

= average velocity of each molecule

m: mass of each molecules

k = Boltzmann constant

dAB: average distance, sum of radii

two identical gas molecules colliding with each other at a velocity,

v (molecules/cm3-s) [N.C. Leuis (1918) and Eyring (1935)]

zAA = # collision/(s-cm3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-62-320.jpg)

![Transition State Theory

]][[

*][**

*

BA

AB

aa

a

K

BA

AB

BA

AB

]][[*

*

BAKr

BA

AB

RT

G

eK

*

*

T

= 6.624x10-27 erg/s

70

K = 1.38x10-16 erg/oK

A + B = AB* C

r = [AB*]; (s-1); [AB*](molecules/cm3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-70-320.jpg)

![Elementary Steps and Molecularity

Molecularity is the number of molecules reacting.

77

Molecularity Elementary Reaction Rate Law

Unimolecular A products Rate = k[A]

Bimolecular A + A products Rate = k[A]2

Bimolecular A + B products Rate = k[A][B]

Trimolecular A + A + A products Rate = k[A]3

Trimolecular A + A + products Rate = k[A]2[B]

Trimolecular A + B + C products Rate = k[A][B][C]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-77-320.jpg)

![79

2N2O5 4NO + O2

N2O5 NO2 + NO3

k1

k-1

NO3 + NO NO + NO2 + O2

k2

NO3 + NO 2NO

k3

0]][[]][[

][

3332 NONOkNONOk

dt

NOd

][

]][[

][

33

232

NOk

NONOk

NO

0]][[]][[]][[][

][

32133232521

3

NONOkNONOkNONOkONk

dt

NOd

]][[]][[]][[

][

][

32133232

521

3

NONOkNONOkNONOk

ONk

NO

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-79-320.jpg)

![80

])[2(

][

][])[(

][

][][][

][

][

212

521

2

3

2

3212

521

21322

521

3

NOkk

ONk

NO

k

k

kNOkk

ONk

NOkNOkNOk

ONk

NO

]['

)2(

][

])[2(

]][[

]][[

][

52

12

52321

212

252321

232

2

ONk

kk

ONkkk

NOkk

NOONkkk

NONOk

dt

Od

r

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-80-320.jpg)

![86

Catalytic efficiency,

= kcat/KM

= k2/[(k-1+k2)/k1]

max, = k1; if k2 >>k-1

k1 = rate of formation of ES

Diffusion limit ~ 108 – 109 M-1-s-1

For enzyme sized molecules at room

temperature

Decomposition of hydrogen peroxide

= 4x108 M-1-s-1

Turnover number or catalytic constant

= number of catalytic cycles performed by the activate

Site in a given time intervals divided by the duration of that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-86-320.jpg)

![87

Lineweaver Burk Plot ][

][max

SK

Sv

v

M

SSv

K

v

M 111

max

maxmax v

S

v

K

v

S M

MM K

v

K

v

S

v

max

1/vmax

KM/vmax

1/v

1/[S]

vmax/KM

1/KM

v/[S]

v

KM/vmax

1/vmax

[S]/v

[S]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-87-320.jpg)

![90

Competitive Inhibition

0][][]][[

][

211 ESkESkSEk

dt

ESd

0][][]][[

][

433 EIkEIkIEk

dt

EId

MK

k

kk

ES

SE

1

21

IK

EI

IE

][][][ EIESEEo

IM

o

K

IE

K

SE

EE

]][[]][[

][

IM

o

K

I

K

S

EE

][][

1][

IM

o

K

I

K

S

E

E

][][

1

][

E + S ES E + P

k1

+

I

EI E + Q

k3

KI

k-1

k2

k-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-90-320.jpg)

![91

][

][

2 ESk

dt

Pd

MK

SE

k

dt

Pd ]][[][

2

][

][][

1

][ 2

S

K

I

K

S

E

K

k

dt

Pd

IM

o

M

][

][

1

][][ 2

S

K

I

K

SEk

dt

Pd

v

I

M

o

oEkv 2max

1/v

[S]

1/vmax

[I]

][

][

1

][max

S

K

I

K

Sv

v

I

M

][

1][

1

11

maxmax SK

I

v

K

vv I

M

I

M

K

I

v

K ][

1

max

Inhibitor is replaced

from the active sites

by substrate at high [S]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-91-320.jpg)

![93

E + S ES E + P

k1

+

I

+

I

EI + S EIS E + P

k3

KI KI

k-1

k2

k-3

][2 ESkv

MIIM

M

KK

SI

K

I

K

S

K

S

v

v

]][[][][

1

][

max

IM

M

K

I

S

K

S

K

S

v

v

][

1][

][

1

][

max

Vmax=k2E0

1/v

1/[S]

1/vmax-app

M

M

K

S

K

][

1

Iapp Kv

I

vv maxmaxmax

][11

1/vmax-app

[I]

1/vmax

1/(vmaxKI)

Henri-Michaelis-Menton Eq](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-93-320.jpg)

![95

][2 ESkv

MIM

M

KK

SI

K

S

K

S

v

v

]][[][

1

][

max

I

M

K

I

vSv

K

v

][

1

1

][

11

maxmax

Vmax=k2E0

1/v

1/[S]

1/v’

[I]

E + S ES E + P

KM

+

I

EIS E + Q

KI

IK

I

v

][

1

1

max

maxv

KM

IK

I

vv

][1

'

1

max

1/vmax

1/KI

Uncompetitive Inhibition](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-95-320.jpg)

![96

PESnSE n

n

n

SE

ES

K

]][[

][

n

n

n

n

SEKE

SEK

ESE

ES

Y

]][[][

]][[

][][

][

n

SK

Y

Y

][

1

KSn

Y

Y

log]log[

1

log

][2 ESkv

][][ ESEEo

n

o SEKEE ]][[][

n

o

SK

E

E

][1

][

n

no

SK

SKE

ES

][1

][

][

n

n

o

n

SK

SKEk

ESkv

][1

][

][ 2

2

maxmax ][

11

v

K

Svv n

Yield

Hill eq.

n: Hill coefficient](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-96-320.jpg)

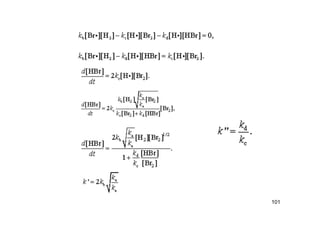

![Chain Reactiosn

98

][

][

''1

]][['][

2

22

2

1

Br

HBr

k

BrHk

dt

HBrd

Chain reactions usually involve free radicals

The experimental rate law is

H2+Br2=2HBr](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-98-320.jpg)

![The Lindemann Mechanism

104

N2O5 = NO2 + NO3.

k1 >> k-2 [N2O5]

Rate k2[N2O5]2

k1 << k-2 [N2O5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-104-320.jpg)

![Langmuir-Hinshelwood

]][[

;

;

;

BSASkR

kSPBSAS

KBSSB

KASSA

s

s

B

A

2

)1( BBAA

BBAA

s

PbPb

PbPb

kR

A

B

s

AA

BB

s

AA

BBAA

s

P

P

k

Pb

Pb

k

Pb

PbPb

kR '

2

)(

2

)( BBAA

BBAA

s

PbPb

PbPb

kR

B

A

s

BB

AA

s

BB

BBAA

s

P

P

k

Pb

Pb

k

Pb

PbPb

kR '

)()( 2

BAs

BBAA

s PPk

PbPb

kR ,

1

115

bBPB <bAPA

bBPB > bAPA

bBPB , bAPA <1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-115-320.jpg)

![Eley-Ridel Equation

skSCASB

KASSA

;

; 1

B

AA

AA

ss P

Pb

Pb

kASbkR

1

]][[

BsB

A

AA

sB

AA

AA

s PkP

P

Pb

kP

Pb

Pb

kR '

1

BAsBAAsB

AA

AB

s PPkPPbkP

Pb

Pb

kR '

1

116](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicalkinetics-171007151323/85/Chemical-kinetics-116-320.jpg)