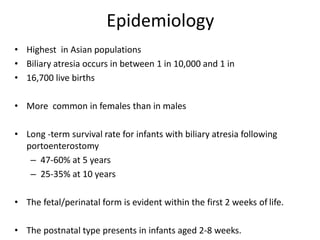

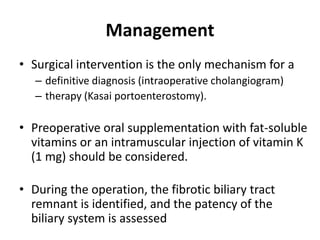

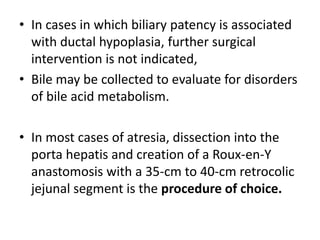

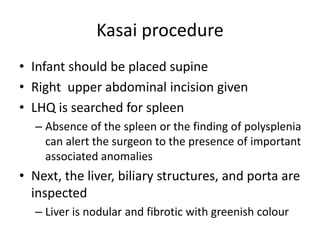

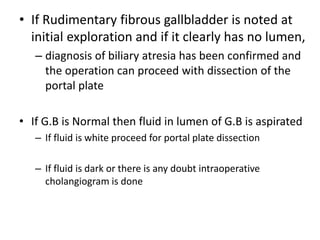

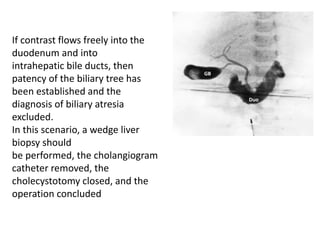

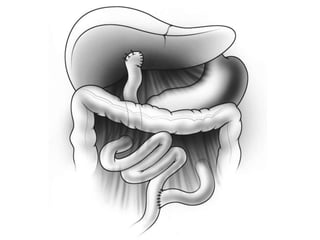

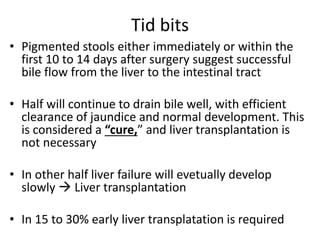

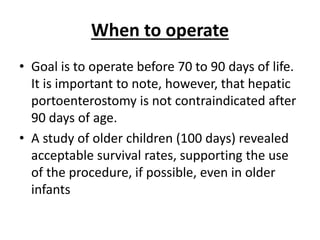

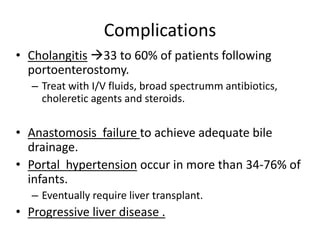

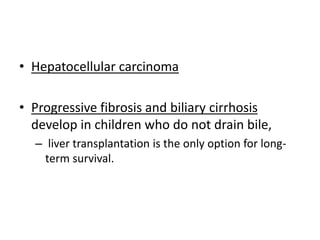

Biliary atresia is a condition where the bile ducts outside the liver are blocked. It is the most common cause of jaundice in newborns that requires surgery. The surgery, called a Kasai procedure, involves removing any remaining blocked bile ducts and connecting the liver directly to the intestine to drain bile. Even with surgery, about half of children will develop progressive liver damage requiring transplantation. Early diagnosis before 3 months of age and surgery improve the chances of successful bile drainage and liver function.