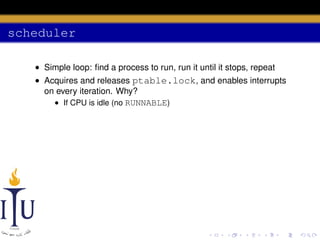

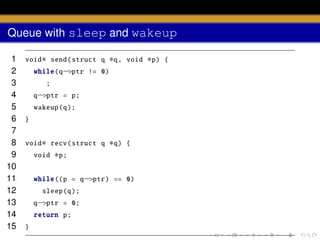

The document discusses process scheduling in an operating system. It describes how an OS runs more processes than it has processors by providing each process with a virtual processor and multiplexing these across physical processors. When a process performs I/O or its time quantum expires, the scheduler selects another process to run using a timer interrupt. Context switching involves saving the context of the current process and restoring the next process using the swtch function. The scheduler runs in a loop, acquiring the process table lock to select a RUNNABLE process and releasing it to allow other CPUs access between iterations.

![scheduler

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

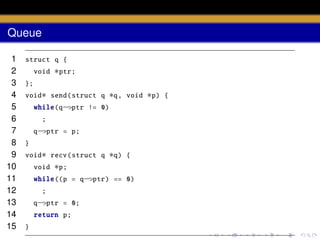

void scheduler (void) {

struct proc

∗p;

for (;;){

sti ();

acquire (& ptable .lock );

for(p = ptable .proc; p < & ptable .proc[ NPROC ]; p++){

if(p−>state != RUNNABLE )

continue ;

proc = p;

switchuvm (p);

p−>state = RUNNING ;

swtch (&cpu−>scheduler , proc−>context );

switchkvm ();

proc = 0;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/document-140110160707-phpapp01/85/AOS-Lab-6-Scheduling-46-320.jpg)

![wakeup

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

static void wakeup1 (void

struct proc

∗chan)

{

∗p;

for(p = ptable .proc; p < & ptable .proc[ NPROC ]; p++)

if(p−>state == SLEEPING && p−>chan == chan)

p−>state = RUNNABLE ;

}

void wakeup (void

∗chan)

acquire (& ptable .lock );

wakeup1 (chan );

release (& ptable .lock );

}

{](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/document-140110160707-phpapp01/85/AOS-Lab-6-Scheduling-57-320.jpg)