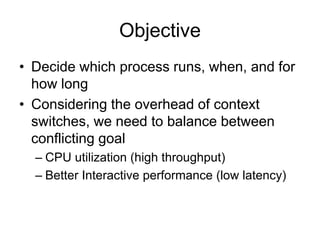

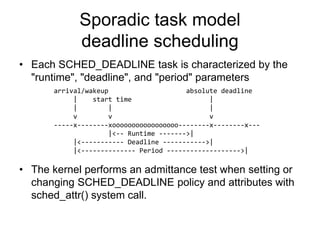

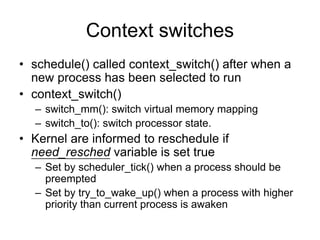

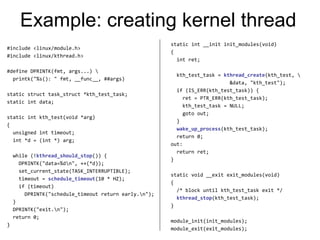

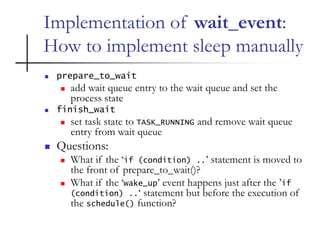

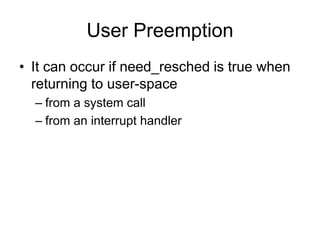

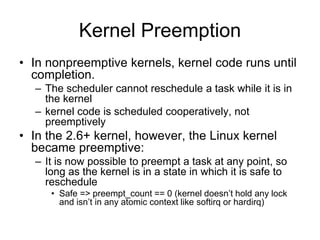

The document discusses process scheduling in operating systems, focusing on objectives, types of processes (I/O-bound and CPU-bound), and various scheduling policies, including cooperative and preemptive multitasking. It details the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), its functioning with time slices, and the implications of process priorities and groups. Additionally, it mentions real-time scheduling and the mechanisms for managing process sleeping and waking in the kernel.

![Process priority

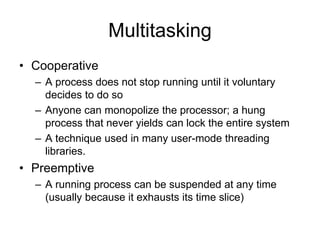

• Processes with a higher priority

– run before those with a lower priority

– receive a longer time slice

• Priority range [static, dynamic]

– Normal, batch: [always 0, -20~+19], default: [0, 0],

dynamic priority is the nice value you adjust in user

space. A larger “nice” value correspond to a lower

priority

– FIFO, RR: [0~99, 0], higher value means greater

priority. FIFO, RR processes are at a higher priority

than normal processes

– Deadline: Not applicable. Deadline processes are

always the highest priority in the system](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processscheduling-170629144609/85/Process-scheduling-6-320.jpg)

![Some tools for real-time tasks

• chrt sets or retrieves the real-time scheduling attributes

of an existing pid, or runs command with the given

attributes.

• Limiting the CPU usage of real-time and deadline

processes

– A nonblocking infinite loop in a thread scheduled under the

FIFO, RR, or DEADLINE policy will block all threads with lower

priority forever

– two /proc files can be used to reserve a certain amount of CPU

time to be used by non-real-time processes.

• /proc/sys/kernel/sched_rt_period_us (default: 1000000)

• /proc/sys/kernel/sched_rt_runtime_us (default: 950000)

chrt [options] [<policy>] <priority> [-p <pid> | <command> [<arg>...]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processscheduling-170629144609/85/Process-scheduling-14-320.jpg)

![Cases that needs preemption disable

• Per-CPU data structures

• Some registers must be protected

– On x86, kernel does not save FPU state

except for user tasks. Entering and exiting

FPU mode is a critical section that must occur

while preemption is disabled

struct this_needs_locking tux[NR_CPUS];

tux[smp_processor_id()] = some_value;

/* task is preempted here... */

something = tux[smp_processor_id()];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processscheduling-170629144609/85/Process-scheduling-28-320.jpg)