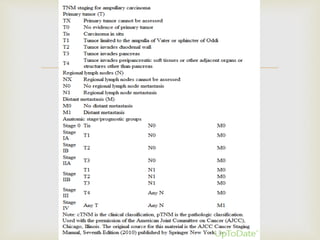

This document discusses ampullary carcinomas, including their epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, staging, treatment, and prognosis. It provides details on: the average age of diagnosis being 60-70 years old; the most common histologic subtype being intestinal (47%); obstructive jaundice being the most common presenting symptom (80%); diagnostic tests including ERCP, CT, and tumor markers; the TNM staging system; pancreaticoduodenectomy being the standard treatment for localized disease; and adjuvant therapy options including chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy for stage IB or higher cancers.

![

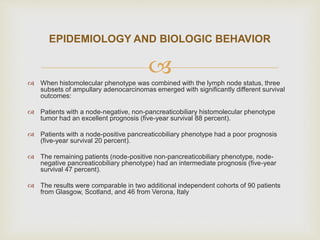

Subdividing adenocarcinomas of the ampulla of Vater according to

histologic subtype and immunohistochemical staining pattern into

distinct subsets with differing biologic behavior has prognostic

importance.

In a retrospective study of 208 patients treated for ampullary

adenocarcinoma in Sydney, Australia,

those with a histomolecular pancreaticobiliary phenotype (CDX-

negative, MUC1 positive) had a significantly worse outcome

than did those with an intestinal phenotype (CDX-positive, MUC1-

negative), with median survival of 16 versus 116 months [22].

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BIOLOGIC BEHAVIOR](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ampullarycarcinoma-140827105523-phpapp02/85/Ampullary-carcinoma-9-320.jpg)

![ Most common presenting symptom of ampullary carcinoma is obstructive jaundice

(80 percent)

Additional symptoms may include diarrhea due to fat malabsorption (steatorrhea),

mild weight loss, and fatigue.

Up to one-third of patients have chronic, frequently occult gastrointestinal blood loss

with an associated microcytic anemia or heme-positive stools.

occasionally present with frank bleeding due to sloughing of the tumor, a condition

exacerbated by the use of antiplatelet agents such as aspirin and clopidogrel.

In one report, nonspecific symptoms include abdominal pain (45 percent), fever (45

percent), mild nausea, and dyspepsia [25].

Large lesions may produce gastric outlet obstruction associated with severe nausea

and vomiting

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ampullarycarcinoma-140827105523-phpapp02/85/Ampullary-carcinoma-11-320.jpg)

![

Endoscopic snare resection (papillectomy) is an effective means of treating

ampullary adenomas.

Endoscopic papillectomy has been attempted in early stage (Tis, T1) well

differentiated ampullary cancers without angiolymphatic invasion

Endoscopic debulking has been used mainly preoperatively to permit stent

insertion and decompression of the biliary tree.

Laser ablation offers the potential for control of local tumor growth in

patients who are unfit for more aggressive therapy. In one such series of

12 patients with ampullary cancer, duodenal obstruction was relieved in

one, and the longest survival was 36 months (median 21 months) [45].

●Compared with laser ablation, photodynamic therapy (PDT) eradicates

local tumor with less surrounding tissue destruction. PDT uses a

photosensitizing drug (a hematoporphyrin derivative, Photofrin®), which is

disproportionately retained by malignant tissue after intravenous

administration.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ampullarycarcinoma-140827105523-phpapp02/85/Ampullary-carcinoma-26-320.jpg)

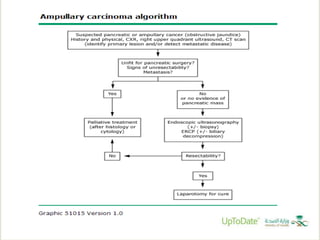

![ Pancreaticoduodenectomy rather than local resection for most patients with invasive

ampullary carcinomas (Grade 1B).

Local ampullary excision rather than pancreaticoduodenectomy for patients with

noninvasive ampullary tumors.

Ampullectomy is also a reasonable approach for poor surgical candidates who have

a well-differentiated T1 tumor that is less than 6 mm in size (based upon endoscopic

ultrasound [EUS]).

However, a more aggressive surgical approach is preferred for patients who are

candidates for pancreaticoduodenectomy because of better outcomes.

Nonsurgical treatment modalities (ie, endoscopic snare resection, laser ablation,

photodynamic therapy) provide palliative rather than curative benefit for patients with

ampullary carcinoma.

These methods should be restricted to patients who are not operative candidates

and those who refuse surgery.

Primary treatment](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ampullarycarcinoma-140827105523-phpapp02/85/Ampullary-carcinoma-27-320.jpg)