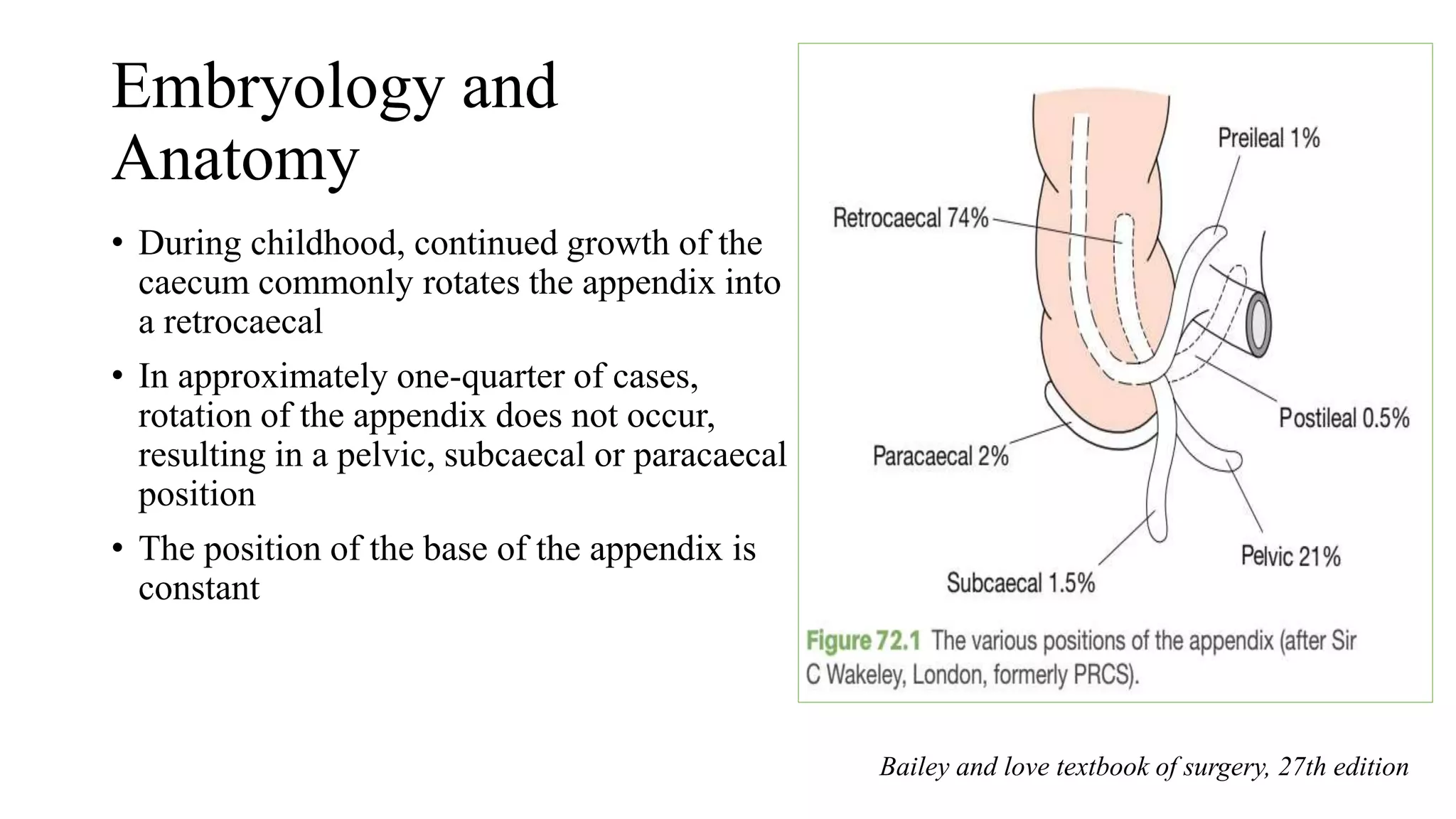

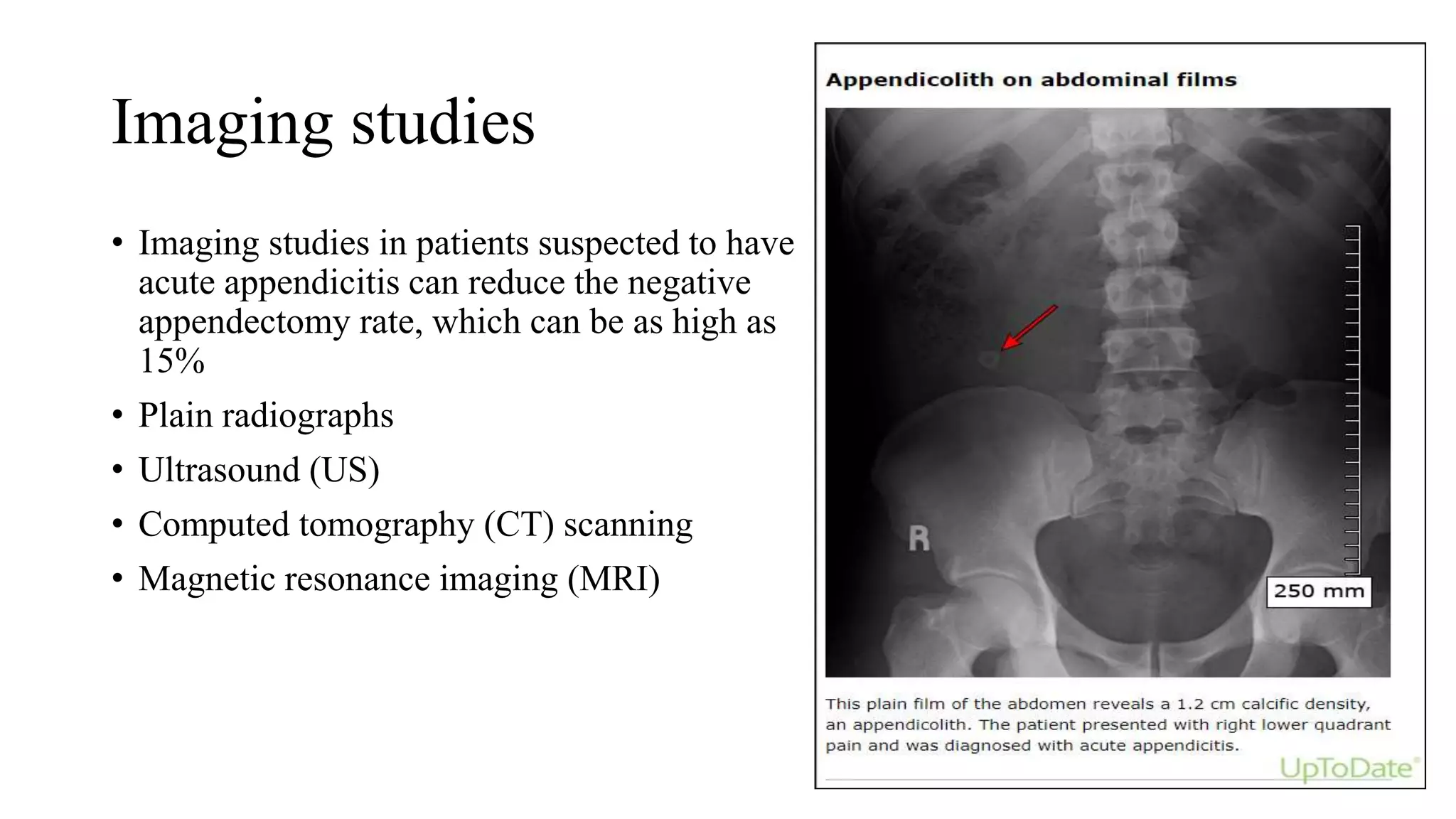

This document provides an overview of acute appendicitis, including its embryology, anatomy, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. It notes that appendicitis is most commonly caused by luminal obstruction and is the most frequent abdominal surgery. Clinical diagnosis involves abdominal pain shifting to the right lower quadrant along with nausea, anorexia, and tenderness. Imaging studies like ultrasound, CT, and MRI can help diagnose appendicitis and reduce negative appendectomy rates. Treatment involves antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated cases or appendectomy, which is most often performed laparoscopically.

![CT-scan

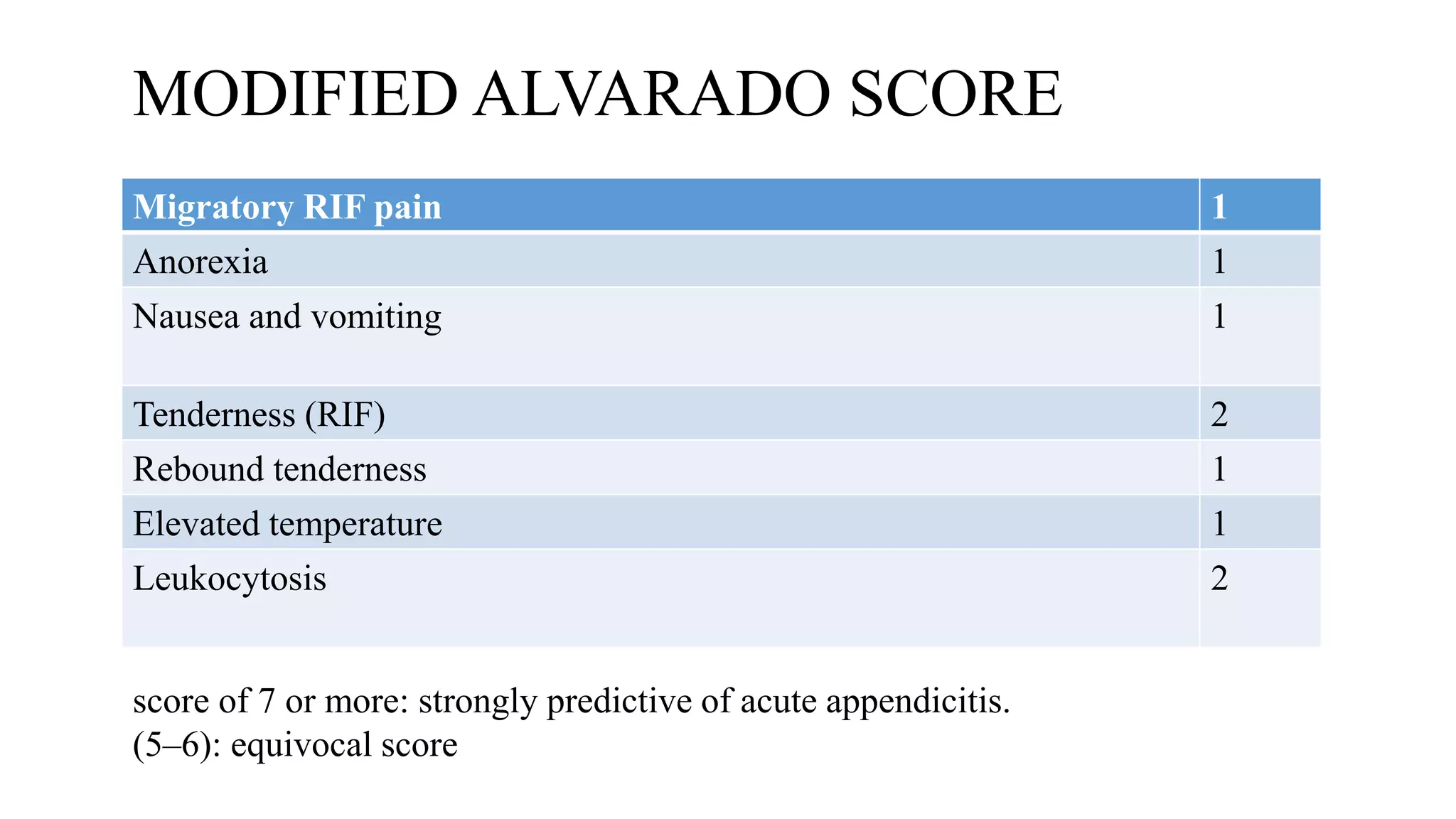

• A contrast-enhanced CT scan has a sensitivity of 0.96 (95% confidence interval

[CI] 0.95–0.97) and specificity of 0.96 (95% CI 0.93–0.97)

• Features on a CT scan that suggest appendicitis include

Enlarged lumen and double wall thickness (greater than 6 mm)

Wall thickening (greater than 2 mm)

Periappendiceal fat stranding

Appendiceal wall thickening and/or

An appendicolith](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acuteappendicties-bydr-230407064549-0df45257/75/Acute-Appendicitis-20-2048.jpg)