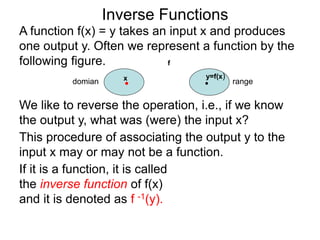

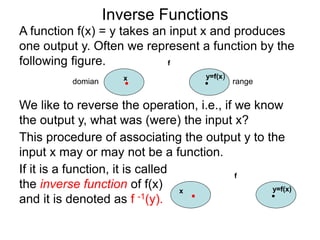

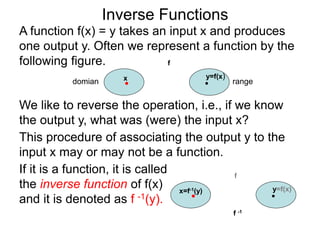

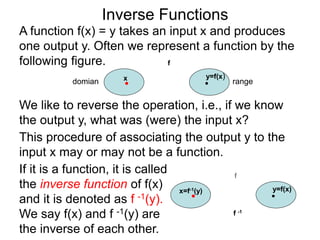

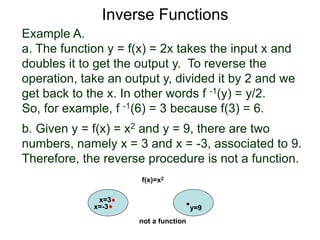

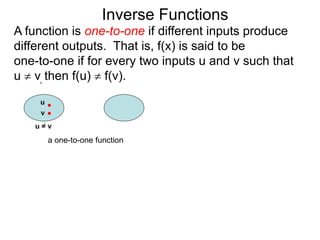

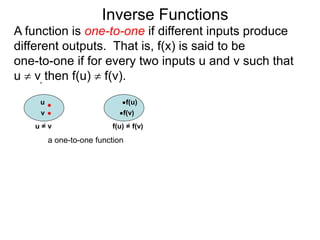

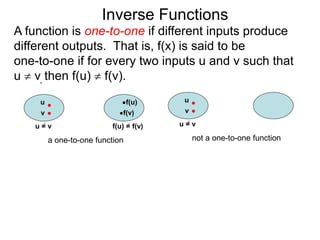

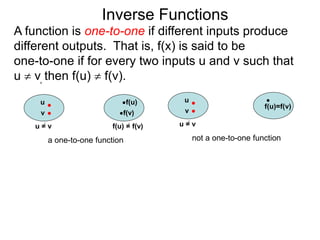

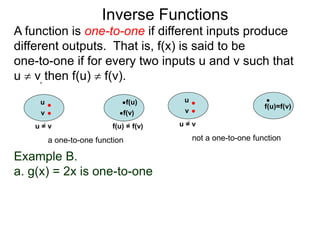

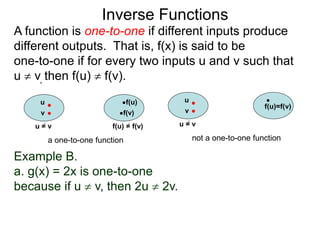

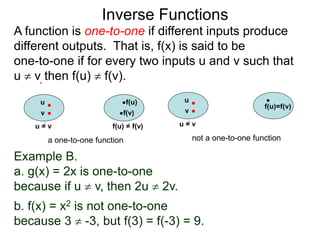

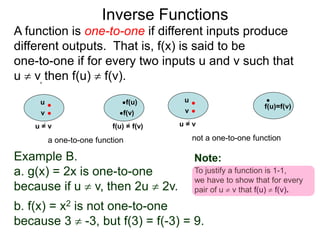

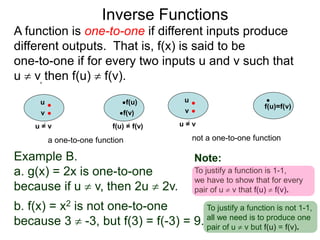

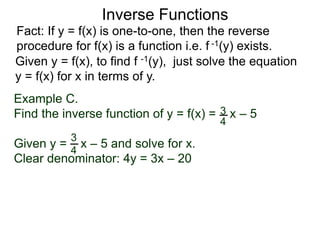

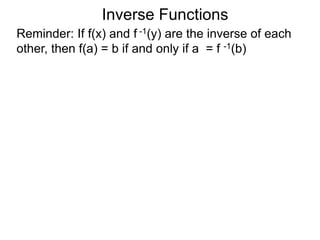

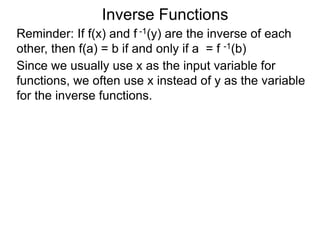

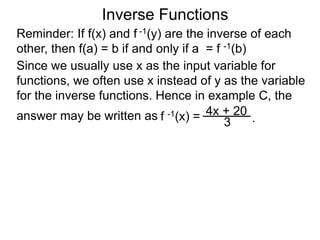

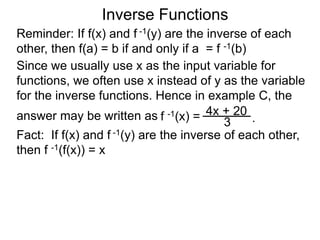

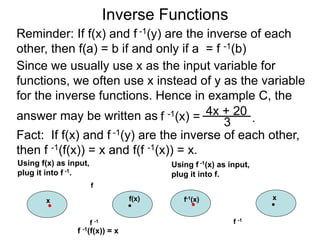

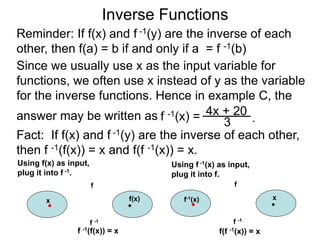

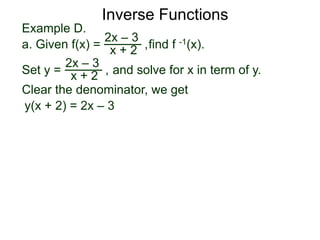

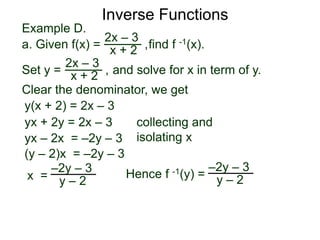

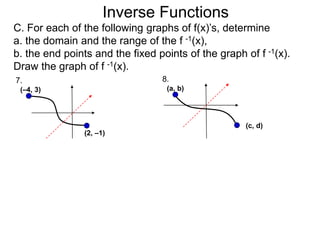

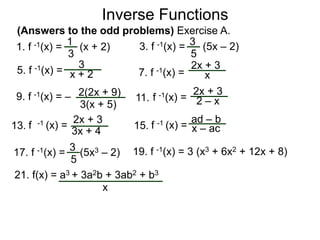

The document discusses inverse functions. An inverse function reverses the input and output of a function. For a function f(x) to have an inverse function f-1(y), it must be one-to-one, meaning that different inputs produce different outputs. The inverse of a function f(x) is found by solving the original function equation for x in terms of y. Examples show finding the inverse of specific functions like f(x) = x - 5 by solving for x. A function is one-to-one if for any two different inputs u and v, their outputs f(u) and f(v) are also different.

![Inverse Functions

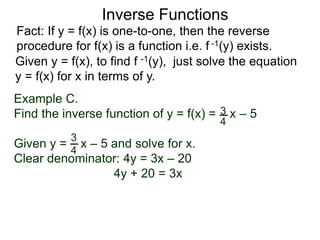

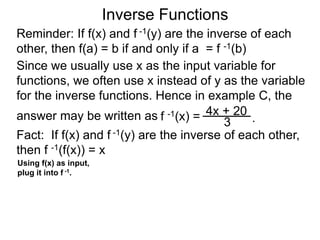

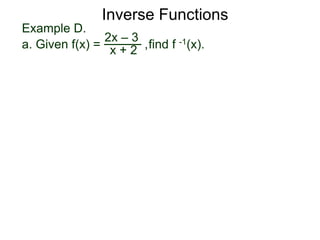

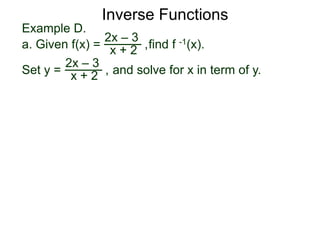

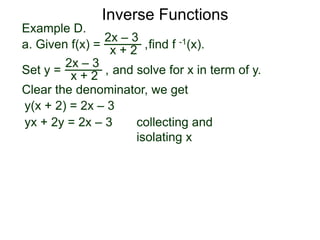

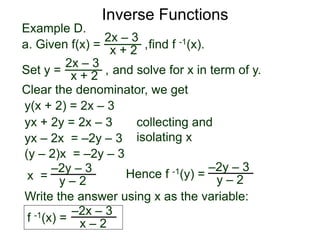

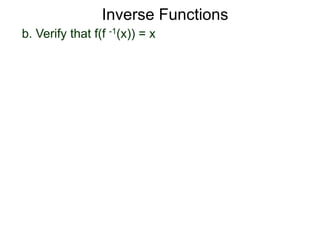

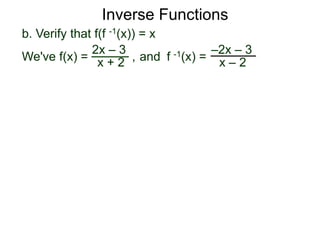

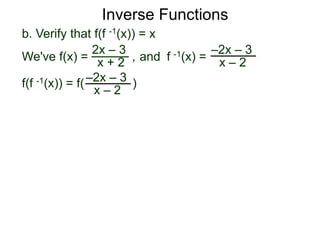

b. Verify that f(f -1(x)) = x

We've f(x) = and

2x – 3

x + 2 , f -1(x) =

–2x – 3

x – 2

f(f -1(x)) = f( )–2x – 3

x – 2

=

–2x – 3

x – 2

– 3

–2x – 3

x – 2

+ 2

( )2[

[ ]

](x – 2)

(x – 2)

Use the LCD to simplify

the complex fraction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-61-320.jpg)

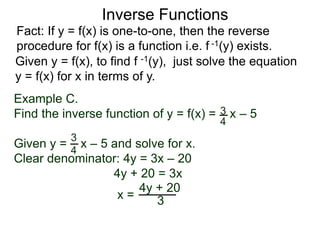

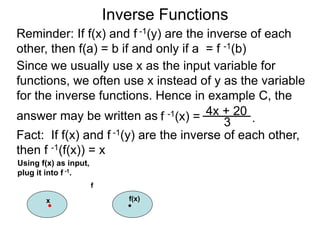

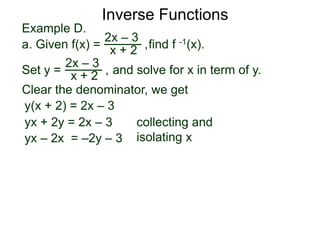

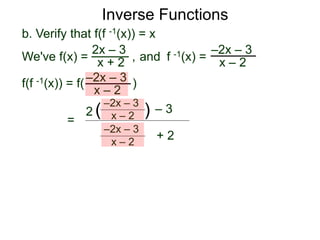

![Inverse Functions

b. Verify that f(f -1(x)) = x

We've f(x) = and

2x – 3

x + 2 , f -1(x) =

–2x – 3

x – 2

f(f -1(x)) = f( )–2x – 3

x – 2

=

–2x – 3

x – 2

– 3

–2x – 3

x – 2

+ 2

( )2[

[ ]

](x – 2)

(x – 2)

=

2(-2x – 3) – 3(x – 2)

(-2x – 3) + 2(x – 2)

Use the LCD to simplify

the complex fraction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-62-320.jpg)

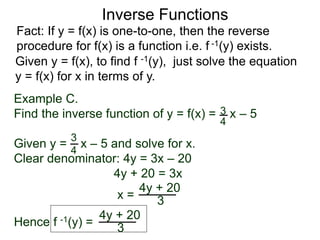

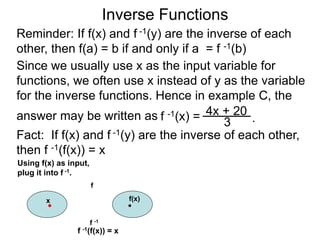

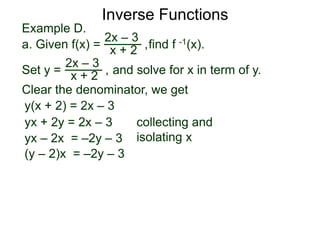

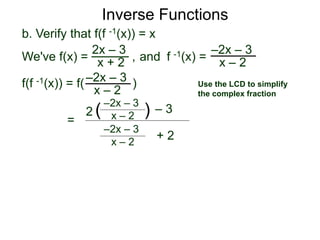

![Inverse Functions

b. Verify that f(f -1(x)) = x

We've f(x) = and

2x – 3

x + 2 , f -1(x) =

–2x – 3

x – 2

f(f -1(x)) = f( )–2x – 3

x – 2

=

–2x – 3

x – 2

– 3

–2x – 3

x – 2

+ 2

( )2[

[ ]

](x – 2)

(x – 2)

=

2(-2x – 3) – 3(x – 2)

(-2x – 3) + 2(x – 2)

=

-4x – 6 – 3x + 6

-2x – 3 + 2x – 4

Use the LCD to simplify

the complex fraction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-63-320.jpg)

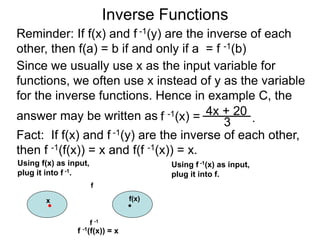

![Inverse Functions

b. Verify that f(f -1(x)) = x

We've f(x) = and

2x – 3

x + 2 , f -1(x) =

–2x – 3

x – 2

f(f -1(x)) = f( )–2x – 3

x – 2

=

–2x – 3

x – 2

– 3

–2x – 3

x – 2

+ 2

( )2[

[ ]

](x – 2)

(x – 2)

=

2(-2x – 3) – 3(x – 2)

(-2x – 3) + 2(x – 2)

=

-4x – 6 – 3x + 6

-2x – 3 + 2x – 4

=

-7x

-7

= x

Your turn. Verify that f -1(f(x)) = x

Use the LCD to simplify

the complex fraction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-64-320.jpg)

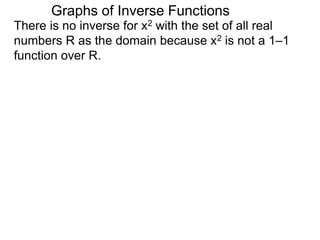

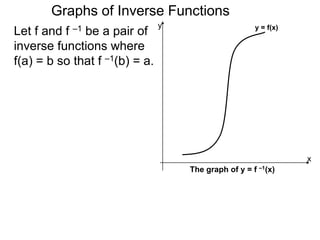

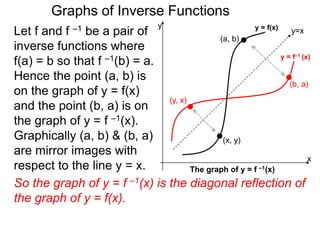

![Graphs of Inverse Functions

y = f–1 (x)

(a, b)

(b, a)

y = f(x)

(x, y)

(y, x)

x

y

(c, c), a fixed point

Let f and f –1 be a pair of

inverse functions where

f(a) = b so that f –1(b) = a.

Hence the point (a, b) is

on the graph of y = f(x)

and the point (b, a) is on

the graph of y = f –1(x).

Graphically (a, b) & (b, a)

are mirror images with

respect to the line y = x.

y=x

So the graph of y = f –1(x) is the diagonal reflection of

the graph of y = f(x). If the domain of f(x) is [A, B]

The graph of y = f –1(x)

A B](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-80-320.jpg)

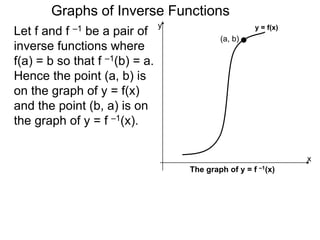

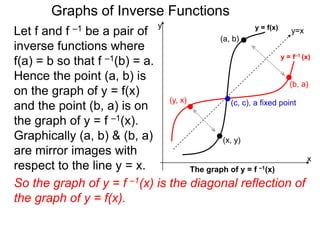

![Graphs of Inverse Functions

y = f–1 (x)

(a, b)

(b, a)

y = f(x)

(x, y)

(y, x)

x

y

(c, c), a fixed point

Let f and f –1 be a pair of

inverse functions where

f(a) = b so that f –1(b) = a.

Hence the point (a, b) is

on the graph of y = f(x)

and the point (b, a) is on

the graph of y = f –1(x).

Graphically (a, b) & (b, a)

are mirror images with

respect to the line y = x.

y=x

So the graph of y = f –1(x) is the diagonal reflection of

the graph of y = f(x). If the domain of f(x) is [A, B] and

its range is [C, D],

The graph of y = f –1(x)

A B

C

D](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-81-320.jpg)

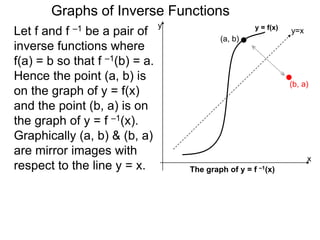

![Graphs of Inverse Functions

y = f–1 (x)

(a, b)

(b, a)

y = f(x)

(x, y)

(y, x)

x

y

(c, c), a fixed point

Let f and f –1 be a pair of

inverse functions where

f(a) = b so that f –1(b) = a.

Hence the point (a, b) is

on the graph of y = f(x)

and the point (b, a) is on

the graph of y = f –1(x).

Graphically (a, b) & (b, a)

are mirror images with

respect to the line y = x.

y=x

So the graph of y = f –1(x) is the diagonal reflection of

the graph of y = f(x). If the domain of f(x) is [A, B] and

its range is [C, D], then the domain of f –1(x) is [C, D],

The graph of y = f –1(x)

A B

C

D

DC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-82-320.jpg)

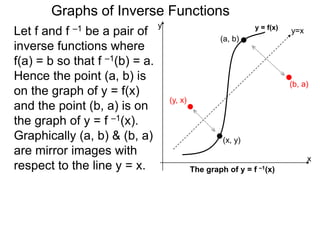

![Graphs of Inverse Functions

y = f–1 (x)

(a, b)

(b, a)

y = f(x)

(x, y)

(y, x)

x

y

(c, c), a fixed point

Let f and f –1 be a pair of

inverse functions where

f(a) = b so that f –1(b) = a.

Hence the point (a, b) is

on the graph of y = f(x)

and the point (b, a) is on

the graph of y = f –1(x).

Graphically (a, b) & (b, a)

are mirror images with

respect to the line y = x.

y=x

So the graph of y = f –1(x) is the diagonal reflection of

the graph of y = f(x). If the domain of f(x) is [A, B] and

its range is [C, D], then the domain of f –1(x) is [C, D],

with [A, B] as its range.

The graph of y = f –1(x)

A B

C

D

B

A

DC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-83-320.jpg)

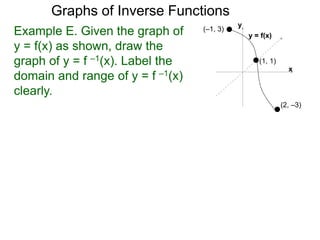

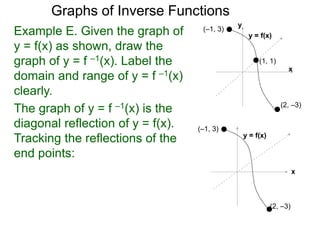

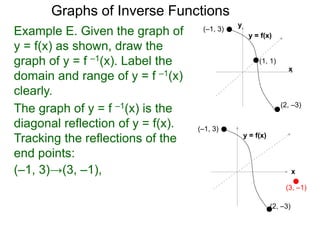

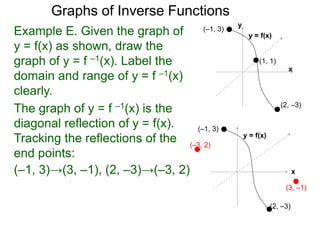

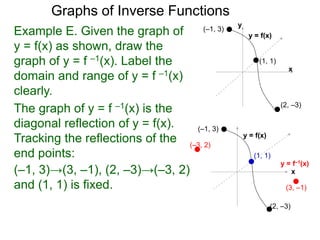

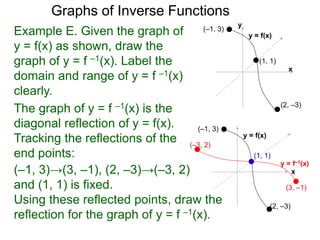

![Graphs of Inverse Functions

(–1, 3)

y = f(x)Example E. Given the graph of

y = f(x) as shown, draw the

graph of y = f –1(x). Label the

domain and range of y = f –1(x)

clearly.

x

y

(1, 1)

(2, –3)

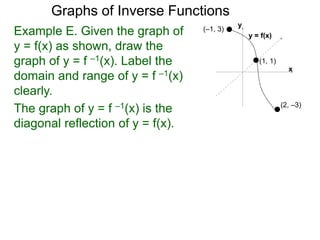

The graph of y = f –1(x) is the

diagonal reflection of y = f(x).

Tracking the reflections of the

end points:

(–1, 3)→(3, –1), (2, –3)→(–3, 2)

and (1, 1) is fixed.

Using these reflected points, draw the

reflection for the graph of y = f –1(x).

(–1, 3)

y = f(x)

x

(1, 1)

(2, –3)

(–3, 2)

(3, –1)

y = f–1(x)

The domain of f –1(x) is [–3, 3] with [–1, 2] as its range.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-91-320.jpg)

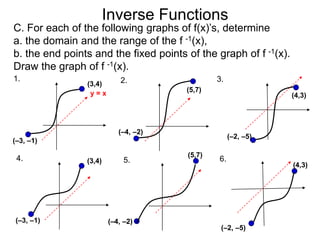

![Exercise C.

Inverse Functions

(4, 3)

y = x

(-1, -3)

1. domain: [-1, 4]

range: [-3, 3]

(–5, –2)

(3,4)

3. domain: [-5, 3]

range: [-2, 4]

(–2, –4)

(7,5)

5. domain: [-2, 7]

range: [-4, 5]

(3, –4)

7. domain: [-1, 3], range: [-4,2]

(–1, 2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-5inversefunctions-110830000619-phpapp01/85/4-1-inverse-functions-97-320.jpg)