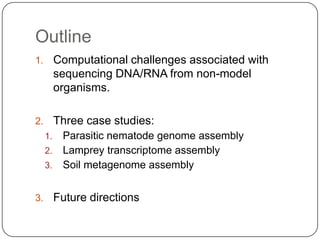

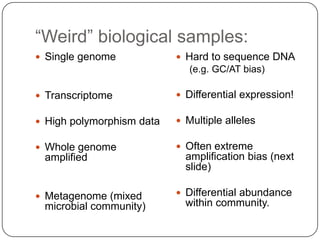

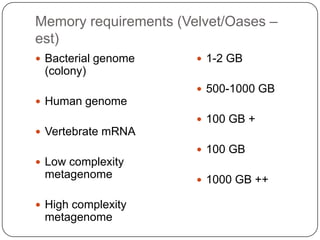

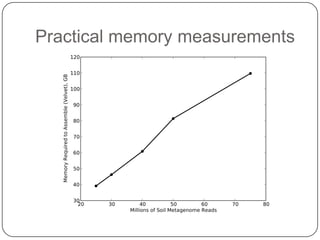

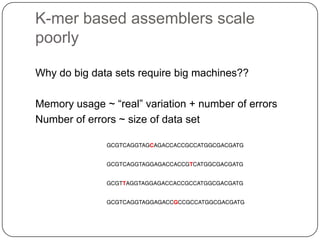

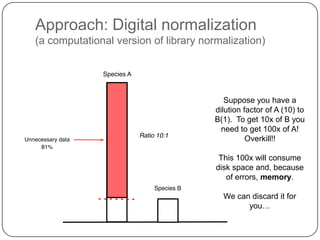

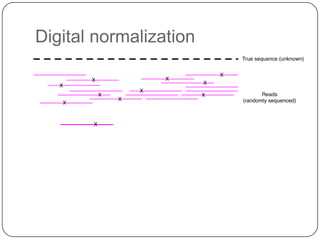

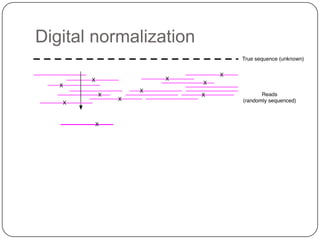

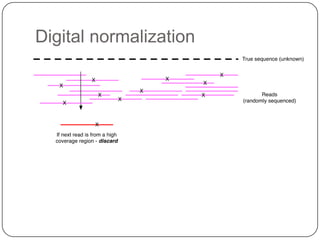

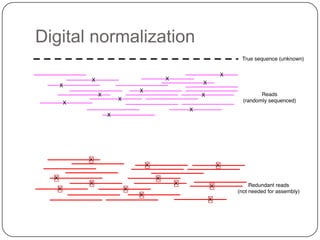

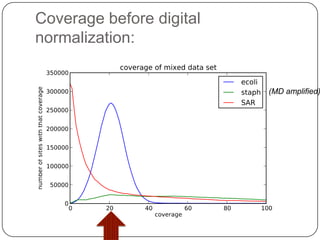

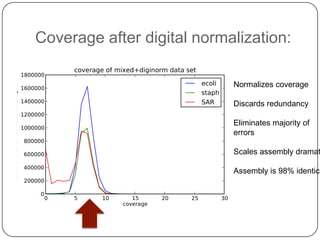

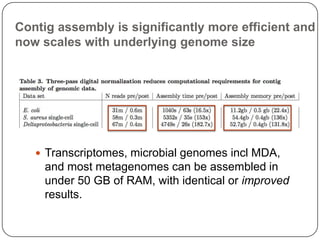

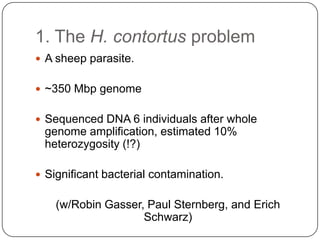

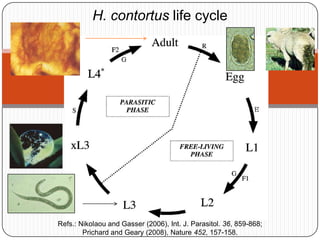

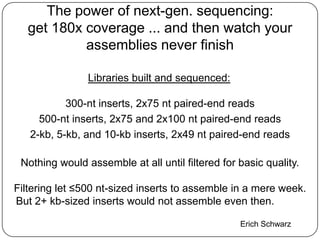

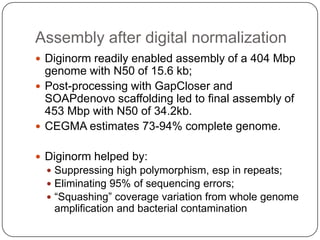

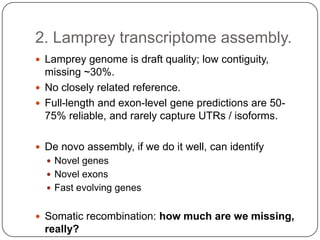

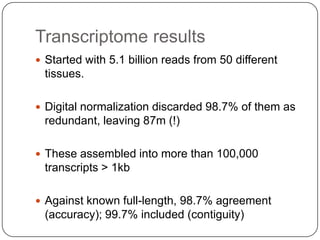

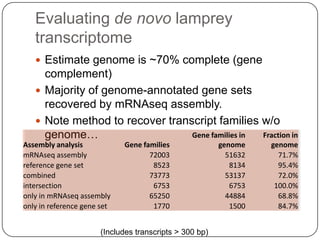

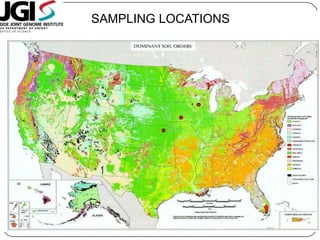

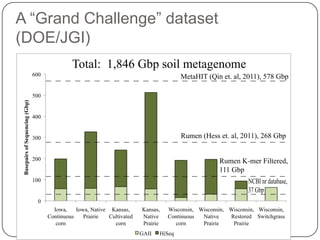

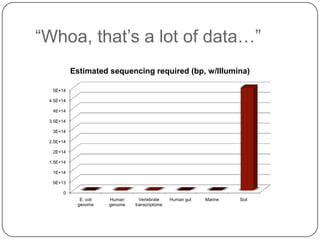

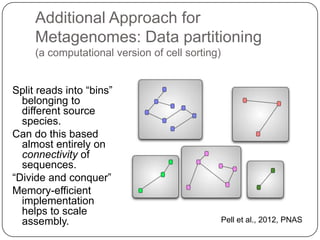

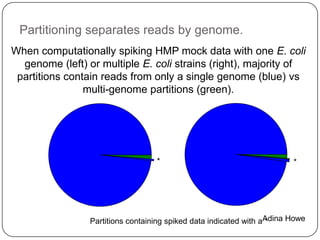

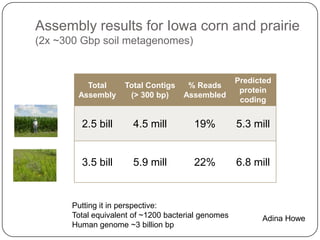

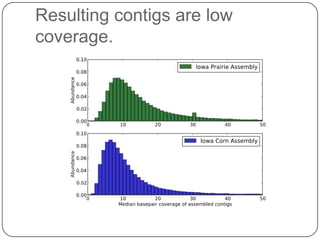

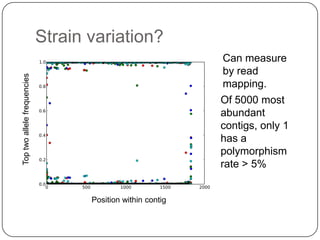

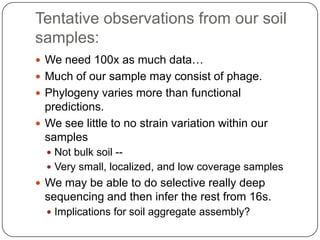

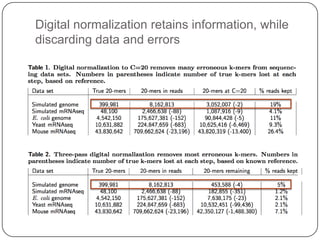

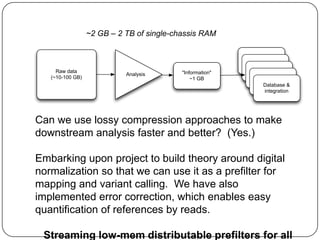

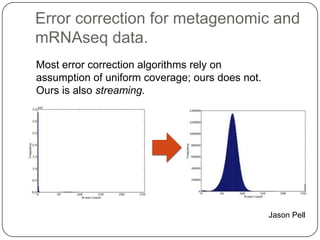

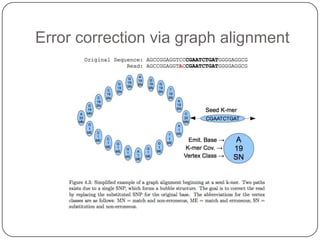

Digital normalization is a new technique for pre-filtering sequencing reads that helps address computational challenges in assembling genomes, transcriptomes, and metagenomes from non-model organisms. It works by discarding redundant reads to smooth coverage and eliminate the majority of errors. Three case studies showed its effectiveness: 1) Assembling the parasitic nematode H. contortus genome, 2) Assembling the lamprey transcriptome without a reference, and 3) Assembling two large soil metagenomes. Digital normalization enabled efficient assemblies and new biological insights in these difficult "weird" samples.