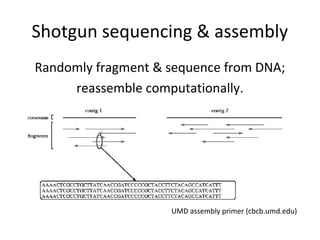

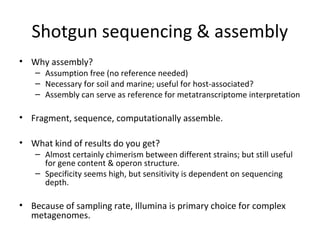

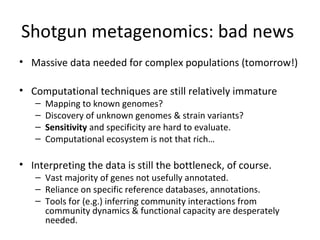

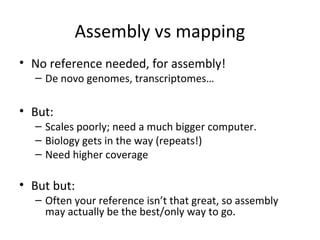

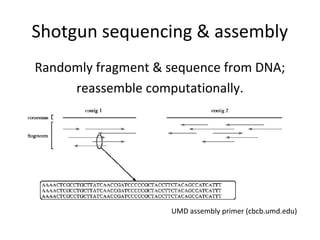

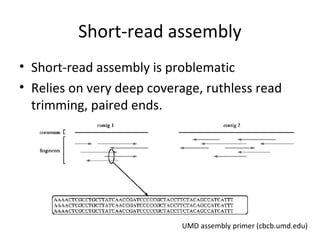

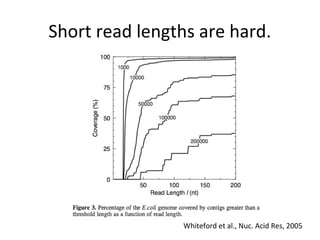

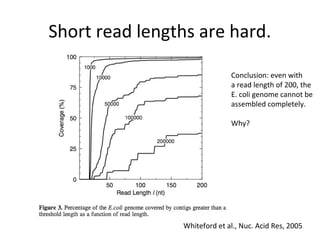

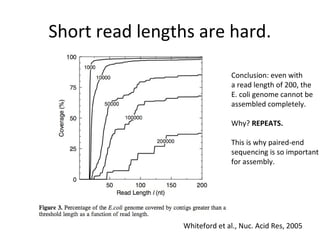

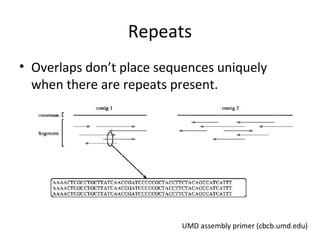

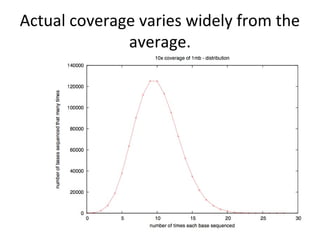

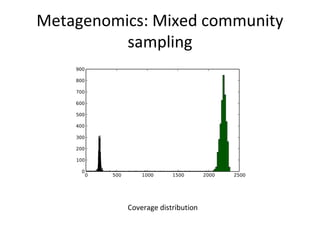

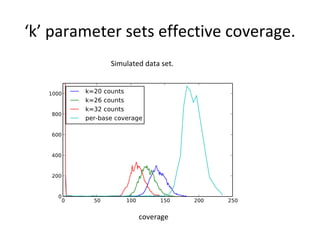

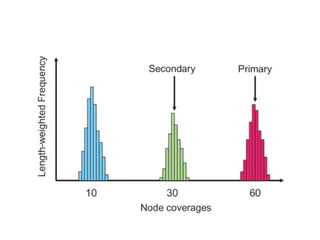

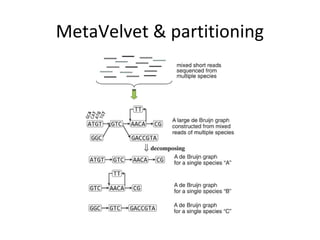

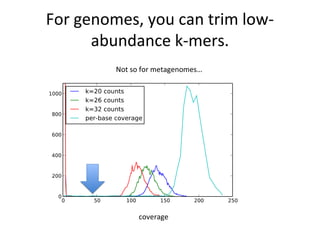

Randomly fragmenting and sequencing DNA from environmental samples, then computationally reassembling it, is known as shotgun metagenomic assembly. It provides an assumption-free way to analyze microbial communities without needing references. However, computational techniques for metagenomic assembly are still immature due to challenges including repeats, varying coverage, errors, and distinguishing biological connections from erroneous ones in assembly graphs. Proper evaluation of metagenomic assemblies also remains a bottleneck.