This document discusses important issues in machine learning for data mining, including the bias-variance dilemma. It explains that the difference between the optimal regression and a learned model can be measured by looking at bias and variance. Bias measures the error between the expected output of the learned model and the optimal regression, while variance measures the error between the learned model's output and its expected output. There is a tradeoff between bias and variance - increasing one decreases the other. This is known as the bias-variance dilemma. Cross-validation and confusion matrices are also introduced as evaluation techniques.

![Images/cinvestav-

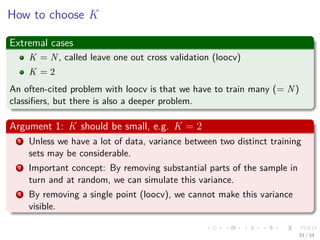

Thus, we have that

Two main functions

A function g (x|D) obtained using some algorithm!!!

E [y|x] the optimal regression...

Important

The key factor here is the dependence of the approximation on D.

Why?

The approximation may be very good for a specific training data set but

very bad for another.

This is the reason of studying fusion of information at decision level...

5 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-11-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Two main functions

A function g (x|D) obtained using some algorithm!!!

E [y|x] the optimal regression...

Important

The key factor here is the dependence of the approximation on D.

Why?

The approximation may be very good for a specific training data set but

very bad for another.

This is the reason of studying fusion of information at decision level...

5 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-12-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Two main functions

A function g (x|D) obtained using some algorithm!!!

E [y|x] the optimal regression...

Important

The key factor here is the dependence of the approximation on D.

Why?

The approximation may be very good for a specific training data set but

very bad for another.

This is the reason of studying fusion of information at decision level...

5 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-13-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Two main functions

A function g (x|D) obtained using some algorithm!!!

E [y|x] the optimal regression...

Important

The key factor here is the dependence of the approximation on D.

Why?

The approximation may be very good for a specific training data set but

very bad for another.

This is the reason of studying fusion of information at decision level...

5 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-14-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Two main functions

A function g (x|D) obtained using some algorithm!!!

E [y|x] the optimal regression...

Important

The key factor here is the dependence of the approximation on D.

Why?

The approximation may be very good for a specific training data set but

very bad for another.

This is the reason of studying fusion of information at decision level...

5 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-15-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

How do we measure the difference

We have that

Var(X) = E((X − µ)2

)

We can do that for our data

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

Now, if we add and subtract

ED [g (x|D)] (2)

Remark: The expected output of the machine g (x|D)

7 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-17-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

How do we measure the difference

We have that

Var(X) = E((X − µ)2

)

We can do that for our data

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

Now, if we add and subtract

ED [g (x|D)] (2)

Remark: The expected output of the machine g (x|D)

7 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-18-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

How do we measure the difference

We have that

Var(X) = E((X − µ)2

)

We can do that for our data

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

Now, if we add and subtract

ED [g (x|D)] (2)

Remark: The expected output of the machine g (x|D)

7 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-19-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

How do we measure the difference

We have that

Var(X) = E((X − µ)2

)

We can do that for our data

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

Now, if we add and subtract

ED [g (x|D)] (2)

Remark: The expected output of the machine g (x|D)

7 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-20-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Or Original variance

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)] + ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

+ ...

...2 ((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x]) + ...

... (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

Finally

ED (((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])) =? (3)

8 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-21-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Or Original variance

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)] + ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

+ ...

...2 ((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x]) + ...

... (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

Finally

ED (((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])) =? (3)

8 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-22-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Or Original variance

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)] + ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

+ ...

...2 ((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x]) + ...

... (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

Finally

ED (((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])) =? (3)

8 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-23-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Thus, we have that

Or Original variance

VarD (g (x|D)) = ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)] + ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

+ ...

...2 ((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x]) + ...

... (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

Finally

ED (((g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])) (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])) =? (3)

8 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-24-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

We have the Bias-Variance

Our Final Equation

ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

VARIANCE

+ (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

Where the variance

It represents the measure of the error between our machine g (x|D) and

the expected output of the machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ).

Where the bias

It represents the quadratic error between the expected output of the

machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ) and the expected output of the optimal

regression.

10 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-26-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

We have the Bias-Variance

Our Final Equation

ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

VARIANCE

+ (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

Where the variance

It represents the measure of the error between our machine g (x|D) and

the expected output of the machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ).

Where the bias

It represents the quadratic error between the expected output of the

machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ) and the expected output of the optimal

regression.

10 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-27-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

We have the Bias-Variance

Our Final Equation

ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

VARIANCE

+ (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

Where the variance

It represents the measure of the error between our machine g (x|D) and

the expected output of the machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ).

Where the bias

It represents the quadratic error between the expected output of the

machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ) and the expected output of the optimal

regression.

10 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-28-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

We have the Bias-Variance

Our Final Equation

ED (g (x|D) − E [y|x])2

= ED (g (x|D) − ED [g (x|D)])2

VARIANCE

+ (ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

Where the variance

It represents the measure of the error between our machine g (x|D) and

the expected output of the machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ).

Where the bias

It represents the quadratic error between the expected output of the

machine under xi ∼ p (x|Θ) and the expected output of the optimal

regression.

10 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-29-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

For this

Assume

The data is generated by the following function

y =f (x) + ,

∼N 0, σ2

We know that

The optimum regressor is E [y|x] = f (x)

Furthermore

Assume that the randomness in the different training sets, D, is due to the

yi’s (Affected by noise), while the respective points, xi, are fixed.

14 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-41-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

For this

Assume

The data is generated by the following function

y =f (x) + ,

∼N 0, σ2

We know that

The optimum regressor is E [y|x] = f (x)

Furthermore

Assume that the randomness in the different training sets, D, is due to the

yi’s (Affected by noise), while the respective points, xi, are fixed.

14 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-42-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

For this

Assume

The data is generated by the following function

y =f (x) + ,

∼N 0, σ2

We know that

The optimum regressor is E [y|x] = f (x)

Furthermore

Assume that the randomness in the different training sets, D, is due to the

yi’s (Affected by noise), while the respective points, xi, are fixed.

14 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-43-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Sampling the Space

Imagine that D ⊂ [x1, x2] in which x lies

For example, you can choose xi = x1 + x2−x1

N−1 (i − 1) with i = 1, 2, ..., N

16 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-45-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Case 1

Since g (x) is fixed

ED [g (x|D)] = g (x|D) ≡ g (x) (4)

With

VarD [g (x|D)] = 0 (5)

On the other hand

Because g (x) was chosen arbitrarily the expected bias must be large.

(ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

(6)

18 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-48-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Case 1

Since g (x) is fixed

ED [g (x|D)] = g (x|D) ≡ g (x) (4)

With

VarD [g (x|D)] = 0 (5)

On the other hand

Because g (x) was chosen arbitrarily the expected bias must be large.

(ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

(6)

18 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-49-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Case 1

Since g (x) is fixed

ED [g (x|D)] = g (x|D) ≡ g (x) (4)

With

VarD [g (x|D)] = 0 (5)

On the other hand

Because g (x) was chosen arbitrarily the expected bias must be large.

(ED [g (x|D)] − E [y|x])2

BIAS

(6)

18 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-50-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Case 2

Due to the zero mean of the noise source

ED [g1 (x|D)] = f (x) = E [y|x] for any x = xi (7)

Remark: At the training points the bias is zero.

However the variance increases

ED (g1 (x|D) − ED [g1 (x|D)])2

= ED (f (x) + − f (x))2

= σ2

, for x = xi, i = 1, 2, ..., N

In other words

The bias becomes zero (or approximately zero) but the variance is now

equal to the variance of the noise source.

20 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-53-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Case 2

Due to the zero mean of the noise source

ED [g1 (x|D)] = f (x) = E [y|x] for any x = xi (7)

Remark: At the training points the bias is zero.

However the variance increases

ED (g1 (x|D) − ED [g1 (x|D)])2

= ED (f (x) + − f (x))2

= σ2

, for x = xi, i = 1, 2, ..., N

In other words

The bias becomes zero (or approximately zero) but the variance is now

equal to the variance of the noise source.

20 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-54-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Case 2

Due to the zero mean of the noise source

ED [g1 (x|D)] = f (x) = E [y|x] for any x = xi (7)

Remark: At the training points the bias is zero.

However the variance increases

ED (g1 (x|D) − ED [g1 (x|D)])2

= ED (f (x) + − f (x))2

= σ2

, for x = xi, i = 1, 2, ..., N

In other words

The bias becomes zero (or approximately zero) but the variance is now

equal to the variance of the noise source.

20 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-55-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Introduction

Something Notable

In evaluating the performance of a classification system, the probability of

error is sometimes not the only quantity that assesses its performance

sufficiently.

For this assume a M-class classification task

An important issue is to know whether there are classes that exhibit a

higher tendency for confusion.

Where the confusion matrix

Confusion Matrix A = [Aij] is defined such that each element Aij is the

number of data points whose true class was i but where classified in class

j.

23 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-60-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Introduction

Something Notable

In evaluating the performance of a classification system, the probability of

error is sometimes not the only quantity that assesses its performance

sufficiently.

For this assume a M-class classification task

An important issue is to know whether there are classes that exhibit a

higher tendency for confusion.

Where the confusion matrix

Confusion Matrix A = [Aij] is defined such that each element Aij is the

number of data points whose true class was i but where classified in class

j.

23 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-61-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

Introduction

Something Notable

In evaluating the performance of a classification system, the probability of

error is sometimes not the only quantity that assesses its performance

sufficiently.

For this assume a M-class classification task

An important issue is to know whether there are classes that exhibit a

higher tendency for confusion.

Where the confusion matrix

Confusion Matrix A = [Aij] is defined such that each element Aij is the

number of data points whose true class was i but where classified in class

j.

23 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-62-320.jpg)

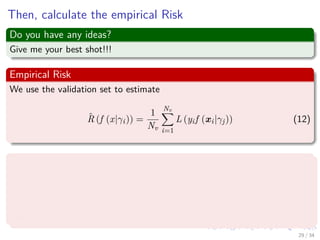

![Images/cinvestav-

What we want

We want to measure

A quality measure to measure different classifiers (for different parameter

values).

We call that as

R(f ) = ED [L (y, f (x))] . (11)

Example: L (y, f (x)) = y − f (x) 2

2

More precisely

For different values γj of the parameter, we train a classifier f (x|γj) on

the training set.

28 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-71-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

What we want

We want to measure

A quality measure to measure different classifiers (for different parameter

values).

We call that as

R(f ) = ED [L (y, f (x))] . (11)

Example: L (y, f (x)) = y − f (x) 2

2

More precisely

For different values γj of the parameter, we train a classifier f (x|γj) on

the training set.

28 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-72-320.jpg)

![Images/cinvestav-

What we want

We want to measure

A quality measure to measure different classifiers (for different parameter

values).

We call that as

R(f ) = ED [L (y, f (x))] . (11)

Example: L (y, f (x)) = y − f (x) 2

2

More precisely

For different values γj of the parameter, we train a classifier f (x|γj) on

the training set.

28 / 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06-151212035935/85/11-Machine-Learning-Important-Issues-in-Machine-Learning-73-320.jpg)