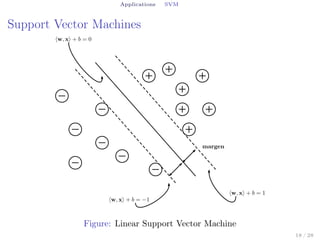

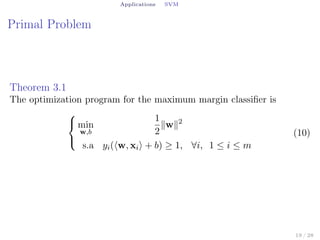

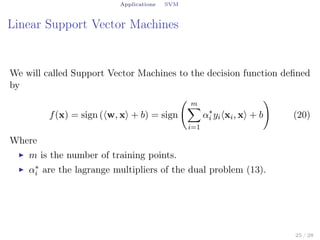

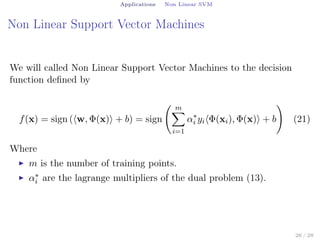

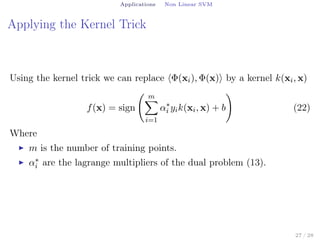

This document summarizes a seminar on kernels and support vector machines. It begins by explaining why kernels are useful for increasing flexibility and speed compared to direct inner product calculations. It then covers definitions of positive definite kernels and how to prove a function is a kernel. Several kernel families are discussed, including translation invariant, polynomial, and non-Mercer kernels. Finally, the document derives the primal and dual problems for support vector machines and explains how the kernel trick allows non-linear classification.

![Kernels

Some Definitions

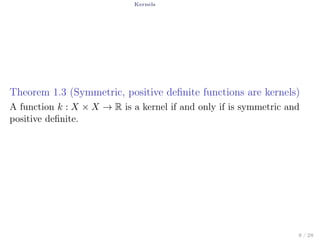

Definition 1.1 (Positive Definite Kernel)

Let X be a nonempty set. A function k : X × X → C is called a

positive definite if and only if

n∑

i=1

n∑

j=1

cicjk(xi, xj) ≥ 0 (1)

for all n ∈ N, {x1, . . . , xn} ⊆ X and {c1, . . . , cn}.

Unfortunately, there is no common use of the preceding definition in

the literature. Indeed, some authors call positive definite function

positive semi-definite, ans strictly positive definite functions are

sometimes called positive definite.

Note:

For fixed x1, x2, . . . , xn ∈ X, then n × n matrix K := [k(xi, xj)]1≤i,j≤n

is often called the Gram Matrix.

6 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-6-320.jpg)

![Kernels

Mercer Condition

Theorem 1.2

Let X = [a, b] be compact interval and let k : [a, b] × [a, b] → C be

continuous. Then φ is positive definite if and only if

∫ b

a

∫ b

a

c(x)c(y)k(x, y)dxdy ≥ 0 (2)

for each continuous function c : X → C.

7 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-7-320.jpg)

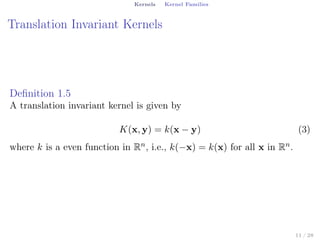

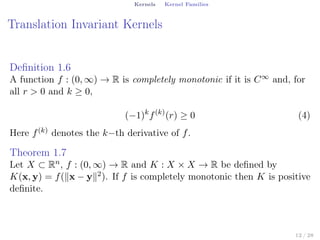

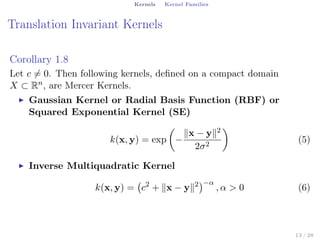

![Kernels Kernel Families

References for Kernels

[3] C. Berg, J. Reus, and P. Ressel. Harmonic Analysis on

Semigroups: Theory of Positive Definite and Related Functions.

Springer Science+Business Media, LLV, 1984.

[9] Felipe Cucker and Ding Xuan Zhou. Learning Theory.

Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[47] Ingo Steinwart and Christmannm Andreas. Support Vector

Machines. 2008.

16 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-16-320.jpg)

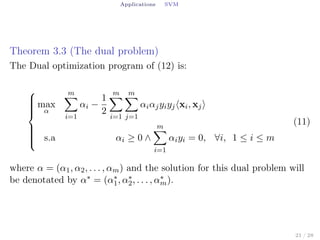

![Applications SVM

Proof.

The Lagrangianx of the function F is

L(x, b, α) =

1

2

∥w∥2

−

m∑

i=1

αi[yi(⟨w, xi⟩ + b) − 1] (12)

Because of the KKT conditions are hold (F is continuous and

differentiable and the restrictions are also continuous and differentiable)

then we can add the complementary conditions

Stationarity:

∇wL = w −

m∑

i=1

αiyixi = 0 ⇒ w =

m∑

i=1

αiyixi (13)

∇bL = −

m∑

i=1

αiyi = 0 ⇒

m∑

i=1

αiyi = 0 (14)

22 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-22-320.jpg)

![Applications SVM

Primal feasibility:

yi(⟨w, xi⟩ + b) ≥ 1, ∀i ∈ [1, m] (15)

Dual feasibility:

αi ≥ 0, ∀i ∈ [1, m] (16)

Complementary slackness:

αi[yi(⟨w, xi⟩+b)−1] = 0 ⇒ αi = 0∨yi(⟨w, xi⟩+b) = 1, ∀i ∈ [1, m] (17)

L(w, b, α) =

1

2

m∑

i=1

αiyixi

2

−

m∑

i=1

m∑

j=1

αiαjyiyj⟨xi, xj⟩

=− 1

2

∑m

i=1

∑m

j=1 αiαjyiyj⟨xi,xj⟩

−

m∑

i=1

αiyib

=0

+

m∑

i=1

αi

(18)

then

L(w, b, α) =

m∑

i=1

αi −

1

2

m∑

i=1

m∑

j=1

αiαjyiyj⟨xi, xj⟩ (19)

23 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-23-320.jpg)

![Applications SVM

Theorem 3.4

Let G a function defined as:

G: Rm

→ R

α → G(α) = αt

Im×m −

1

2

αt

Aα

where α = (α1, α2, . . . , αm) y A = [yiyj⟨xi, xj⟩]1≤i,j≤m in Rm×m then

the following affirmations are hold:

1. The A is symmetric.

2. The function G is differentiable and

∂G(α)

∂α

= Im×m − Aα.

3. The function G is twice differentiable and

∂2G(α)

∂α2

= −A.

4. The function G is a concave function.

24 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-24-320.jpg)

![Applications Non Linear SVM

References for Support Vector Machines

[31] Mehryar Mohri, Afshin Rostamizadeh, and Ameet Talwalkar.

Foundations of Machine Learning. The MIT Press, 2012.

28 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/second-lecture-150902220946-lva1-app6891/85/Kernels-and-Support-Vector-Machines-28-320.jpg)