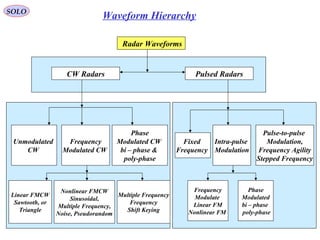

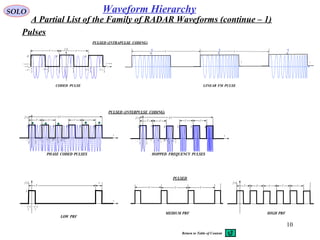

The document covers radar signal processing concepts, including the generation and reception of radar signals, Fourier transforms, and Doppler effects. It discusses signal modulation, range estimation, and digital signal processing techniques used to detect targets. Various radar waveforms and types, as well as mathematical relationships in radar signal processing, are also explained.

![4

SOLO

The transmitted RADAR RF

Signal is:

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]ttftEtEt 0000 2cos ϕπ +=

E0 – amplitude of the signal

f0 – RF frequency of the signal

φ0 –phase of the signal (possible modulated)

The returned signal is delayed by the time that takes to signal to reach the target and to

return back to the receiver. Since the electromagnetic waves travel with the speed of light

c (much greater then RADAR and

Target velocities), the received signal

is delayed by

c

RR

td

21 +

≅

The received signal is: ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttfttEtE dddr +−+−⋅−= ϕπα 00 2cos

To retrieve the range (and range-rate) information from the received signal the

transmitted signal must be modulated in Amplitude or/and Frequency or/and Phase.

ά < 1 represents the attenuation of the signal

RADAR Signal Processing

RADAR Signals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-4-320.jpg)

![5

SOLO

The received signal is:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttfttEtE dddr +−+−⋅−= ϕπα 00 2cos

( ) ( ) tRRtRtRRtR ⋅+=⋅+= 222111 &

We want to compute the delay time td due to the time td1 it takes the EM-wave to reach

the target at a distance R1 (at t=0), from the transmitter, and to the time td2 it takes the

EM-wave to return to the receiver, at a distance R2 (at t=0) from the target. 21 ddd ttt +=

According to the Special Theory of Relativity

the EM wave will travel with a constant

velocity c (independent of the relative

velocities ).21 & RR

The EM wave that reached the target at

time t was send at td1 ,therefore

( ) ( ) 111111 ddd tcttRRttR ⋅=−⋅+=− ( )

1

11

1

Rc

tRR

ttd

+

⋅+

=

In the same way the EM wave received from the target at time t was reflected at td2 ,

therefore

( ) ( ) 222222 ddd tcttRRttR ⋅=−⋅+=− ( )

2

22

2

Rc

tRR

ttd

+

⋅+

=

RADAR Signal Processing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-5-320.jpg)

![6

SOLO

The received signal is:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttfttEtE dddr +−+−⋅−= ϕπα 00 2cos

21 ddd ttt += ( )

1

11

1

Rc

tRR

ttd

+

⋅+

= ( )

2

22

2

Rc

tRR

ttd

+

⋅+

=

( ) ( )

2

22

1

11

21

Rc

tRR

Rc

tRR

tttttttt ddd

+

⋅+

−

+

⋅+

−=−−=−

+

−

+

−

+

+

−

+

−

=−

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

Rc

R

t

Rc

Rc

Rc

R

t

Rc

Rc

tt d

From which:

or:

Since in most applications we can

approximate where they appear in the arguments of E0 (t-td), φ (t-td),

however, because f0 is of order of 109

Hz=1 GHz, in radar applications, we must use:

cRR <<21,

1,

2

2

1

1

≈

+

−

+

−

Rc

Rc

Rc

Rc

( )

−⋅

++

−⋅

+=

−⋅

−+

−⋅

−⋅≈− 2

.

201

.

10

22

0

11

00

2

1

2

1

2

12

1

2

12

1

21

D

Ralong

FreqDoppler

DD

Ralong

FreqDoppler

Dd ttffttff

c

R

t

c

R

f

c

R

t

c

R

fttf

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttffttEtE ddDdr +−+−⋅+−= ˆˆˆ2cosˆ 00 ϕπα

where 21

2

2

1

121

2

02

1

01

ˆˆˆ,,,ˆˆˆ,

2ˆ,

2ˆ

dddddDDDDD ttt

c

R

t

c

R

tfff

c

R

ff

c

R

ff +=≈≈+=−≈−≈

Finally

RADAR Signal Processing

Doppler Effect](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-6-320.jpg)

![7

SOLO

The received signal model:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttffttEtE ddDdr +−+−⋅+−≈ ϕπα 00 2cos

Delayed by two-

way trip time

Scaled down

Amplitude Possible phase

modulated

Corrupted

By noise

Doppler

effect

We want to estimate:

• delay td range c td/2

• amplitude reduction α

• Doppler frequency fD

• noise power n (relative to signal power)

• phase modulation φ

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-7-320.jpg)

![9

SOLO

( )tf

2

τ

2

τ

−

A

∞→t

2

τ

+T

2

τ

−T

A

2

τ

+−T

2

τ

−−T

A

t←∞−

T T

NONCOHERENT PULSESCOHERENT PULSES

( )tf

t

A

2

τ

2

τ

−T

AA

T T

A

2

2

τ

+T

2

2

τ

−T

A

T T

A

2

τ

− 2

τ

+T

TN

PULSED (UNCODED)

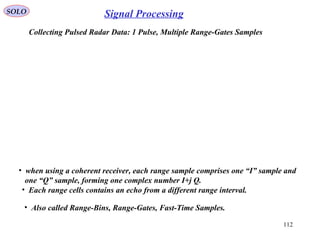

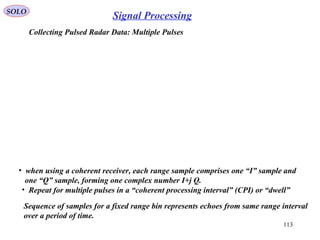

A Partial List of the Family of RADAR Waveforms

PRI – Pulse Repetition Interval PRF – Pulse Repetition Frequency

τ – Pulse Width [μsec]

PRF = 1/PRI

Pulse Duty Cycle = DC = τ / PRI = τ * PRF

Paverrage = DC * Ppeak

Pulse Waveform Parameters

Continuous Waves (CW)

Pulses

• Coherent – Phase is predictable from pulse-to-pulse

• Non-coherent – Phase from pulse-to-pulse is not predictable

Waveform Hierarchy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-9-320.jpg)

![12

SOLO

Radar Generic Procedures:

Matched Filters in RADAR Systems

• Transmits high frequency (f0) EM signal: ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]ttftEtEt 0000 2cos ϕπ +=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttffttEtE ddDdr +−+−⋅+−≈ ϕπα 00 2cos

• Receives low power reflected EM signal that contains doppler information (f0 + fD):

• Down-converts to Intermediate Frequency (IF) signal (fIF + fD), Amplifies at Low Noise,

and Automatically Controls the Gain (AGC) of the receiver:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tnoisettttffttEGtE IFddDIFdIFIF +−+−⋅+−≈ ϕπα 2cos0

• Down-converts to Video Frequency (V) signal (fV + fD), (often using a Synchronous I,Q

configuration), samples the video (A/D) for Digital Signal Processing.

• The Digital Signal Processing (DSP) performs Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT),

to produce the Data Cube (Range, Doppler, Receiving Channels). Using the data

DSP detects the potential targets, and computes the receiving delay td (Range),

Doppler frequency (closing velocity), angular target position. According to the

Radar policy, he will acquire the targets of interest, and will track them.

Doing this he prevents unwanted signal (Clutter, ECM, …) to interfere with

the target of interest received signals.

This presentation deals with some aspects of the Radar Digital Processing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-12-320.jpg)

![14

Fourier Transform

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−== dttjtftfF ωω exp:F

SOLO

Jean Baptiste Joseph

Fourier

1768-1830

F (ω) is known as Fourier Integral or Fourier Transform

and is in general complex

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]ωφωωωω jAFjFF expImRe =+=

Using the identities

( ) ( )t

d

tj δ

π

ω

ω =∫

+∞

∞− 2

exp

we can find the Inverse Fourier Transform ( ) ( ){ }ωFtf -1

F=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

2

exp

2

expexp

2

exp

++−=−=−=

−=

∫∫ ∫

∫ ∫∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

tftfdtfd

d

tjf

d

tjdjf

d

tjF

ττδττ

π

ω

τωτ

π

ω

ωττωτ

π

ω

ωω

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

==

π

ω

ωωω

2

exp:

d

tjFFtf -1

F

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

++−=−∫

+∞

∞−

tftfdtf ττδτ

If f (t) is continuous at t, i.e. f (t-0) = f (t+0)

This is true if (sufficient not necessary)

f (t) and f ’ (t) are piecewise continue in every finite interval1

2 and converge, i.e. f (t) is absolute integrable in (-∞,∞)( )∫

+∞

∞−

dttf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-14-320.jpg)

![15

( )atf −

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω ajF −exp

Fourier TransformSOLO

( )tf

-1

F

F

( )ωFProperties of Fourier Transform (Summary)

Linearity1

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )ωαωαωαααα 221122112211 exp: FFdttjtftftftf +=−+=+ ∫

+∞

∞−

F

Symmetry2

( )tF

-1

F

F

( )ωπ −f2

Conjugate Functions3 ( )tf *

-1

F

F

( )ω−*

F

Scaling4 ( )taf

-1

F

F

a

F

a

ω1

Derivatives5 ( ) ( )tftj

n

−

-1

F

F ( )ω

ω

F

d

d

n

n

( )tf

td

d

n

n

-1

F

F

( ) ( )ωω Fj

n

Convolution6

( ) ( )tftf 21

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω 21

* FF( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−= τττ dtfftftf 2121

:*

-1

F

F ( ) ( )ωω 21

FF

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

= ωωω

π

dFFdttftf 2

*

12

*

1

2

1

Parseval’s Formula7

Shifting: for any a real8

( ) ( )tajtf exp

-1

F

F ( )aF −ω

Modulation9 ( ) ttf 0

cos ω -1

F

F

( ) ( )[ ]00

2

1

ωωωω −++ FF

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

−=−= ωωω

π

ωωω

π

dFFdFFdttftf 212121

2

1

2

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-15-320.jpg)

![20

( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−

= ωω

π

ω

dejF

j

tf tj

2

1

Signal

( )

( )

( ) ( )( ) ( )( )[ ]

−++

+=

±±=>−

≤−≤−

=

∑

∞

=1

000

0

coscos

2

2

sin

cos

,2,1,0,2/0

2/2/cos

n

PRPR

PR

PR

series

Fourier

tntn

n

n

t

T

A

kkkTt

kTttA

tf

ωωωω

τω

τω

ω

τ

τ

ττω

τ - pulse width

Frequency

( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

= dtetfjF tjω

ω

Fourier Transform

Fourier Transform

0ω - carrier frequency

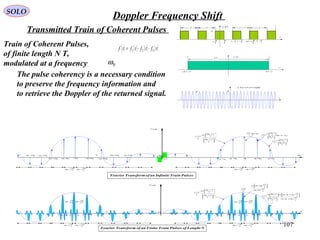

5) Train of Coherent Pulses,

of infinite length,

modulated at a frequency 0ω

T - Pulse repetition interval (PRI)

( ) ( ) ( ){

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

+−+−+−−++

+

−+=

∑

∞

=1

0000

00

2

2

sin

2

n

PRPRPRPR

PR

PR

nnnn

n

n

T

A

jF

ωωδωωδωωδωωδ

τω

τω

ωδωδ

τ

ω

T/1 - Pulse repetition frequency (PRF)

TPR /2πω =

SOLO

Fourier Transform of a Signal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-20-320.jpg)

![21

( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−

= ωω

π

ω

dejF

j

tf tj

2

1

Signal

( )

( )

( ) ( )( ) ( )( )[ ]

−++

+=

±±=>−

≤−≤−

=

∑

∞

=

≤≤−

1

000

22

0

coscos

2

2

sin

cos

2/,,2,1,0,2/0

2/2/cos

n

PRPR

PR

PRNT

t

NT

tntn

n

n

t

T

A

NkkkTt

kTttA

tf

ωωωω

τω

τω

ω

τ

τ

ττω

τ - pulse width

Frequency

( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

= dtetfjF tjω

ω

Fourier Transform

Fourier Transform

0ω - carrier frequency

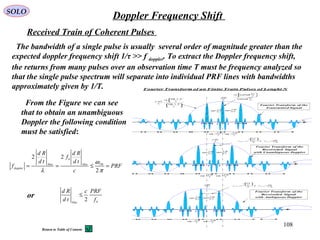

6) Train of Coherent Pulses,

of finite length N T,

modulated at a frequency 0ω

T - Pulse repetition interval (PRI)

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

−−

−−

+

+−

+−

+

+

+

+

−+

−+

+

++

++

+

+

+

=

∑

∑

∞

=

∞

=

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

2

sin

2

n

PR

PR

PR

PR

PR

PR

n

PR

PR

PR

PR

PR

PR

TN

n

TN

n

TN

n

TN

n

n

n

TN

TN

TN

n

TN

n

TN

n

TN

n

n

n

TN

TN

T

A

jF

ωωω

ωωω

ωωω

ωωω

τω

τω

ωω

ωω

ωωω

ωωω

ωωω

ωωω

τω

τω

ωω

ωω

τ

ω

T/1 - Pulse repetition frequency (PRF)

TPR /2πω =

SOLO

Fourier Transform of a Signal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-21-320.jpg)

![22

Signal

( ) ( )

+=

±±=>−

≤−≤−

= ∑

∞

=1

1 cos

2

2

sin

21

,2,1,0,2/0

2/2/

n

PR

PR

PR

Series

Fourier

tn

n

n

T

A

kkkTt

kTtA

tf ω

τω

τω

τ

τ

ττ

τ - pulse width

0ω - carrier frequency

6) Train of Coherent Pulses,

of finite length N T,

modulated at a frequency 0ω

T - Pulse repetition interval (PRI)

T/1 - Pulse repetition frequency (PRF)

TPR /2πω =

( ) ( )tAtf 03 cos ω=

t

A A

( )tf1

t

2

τ

2

τ

−T

A

T T

2

2

τ+T

2

2

τ−T

T T

2

τ− 2

τ+T

( )tf2

t

TN

2/TN2/TN−

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tftftftf 321 ⋅⋅=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )( ) ( )( )[ ]

−++

+=

±±=>−

≤−≤−

=⋅⋅=

∑

∞

=

≤≤−

1

000

22

0

321

coscos

2

2

sin

cos

2/,,2,1,0,2/0

2/2/cos

n

PRPR

PR

PRNT

t

NT

tntn

n

n

t

T

A

NkkkTt

kTttA

tftftftf

ωωωω

τω

τω

ω

τ

τ

ττω

( )

>

≤≤−

=

2/0

2/2/1

2

TNt

TNtTN

tf ( ) ( )ttf 03 cos ω=

SOLO

Fourier Transform of a Signal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-22-320.jpg)

![25

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Waveforms

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

a (t) – nonnegative function that represents any amplitude modulation (AM)

θ (t) – phase angle associated with any frequency modulation (FM)

ω0 – nominal carrier angular frequency ω0 = 2 π f0

f0 – nominal carrier frequency

Transmitted Signal

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]{ }ttjtats θω += 0exp

Phasor (complex) Transmitted Signal

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-25-320.jpg)

![26

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Quadrature Form

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )tttattta

tttats

00

0

sinsincoscos

cos

ωθωθ

θω

−=

+=

where: ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]ttats

ttats

Q

I

θ

θ

sin

cos

=

=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )ttsttsts QI 00 sincos ωω −=

One other form: ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]tjtjtjtj

ee

ta

tttats θωθω

θω −−+

+=+= 00

2

cos 0

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtj

etgetgts 00 *

2

1 ωω −

+= ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tj

QI etatsjtstg θ

=+=:

Envelope of the signal

( ) ( ) tj

etgts 0ω

=

Phasor (complex) Transmitted Signal

Transmitted Signal

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-26-320.jpg)

![27

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Spectrum

Define the Fourier Transfer F

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−== dttjtstsS ωω exp:F ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

==

π

ω

ωωω

2

exp:

d

tjSSts 1-

F

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtj

etgetgts 00 *

2

1 ωω −

+= ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]0

*

0

2

1

ωωωωω −−+−= GGS-1

F

F

-1

F

F

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tj

QI etatsjtstg θ

=+=:

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

Inverse Fourier Transfer F -1

Envelope of the signalWe defined:

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-27-320.jpg)

![28

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Energy ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]{ } ( )∫∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

≈++== dttadttttadttsEs

2

0

22

2

1

22cos1

2

1

: θω

Parseval’s Formula

Proof:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

= ωωω

π

dFFdttftf 2

*

12

*

1

2

1

( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−= dttjtfF ωω exp11

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫ ∫∫ ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

=−=−=

π

ω

ωω

π

ω

ωω

π

ω

ωω

22

exp

2

exp 2

*

112

*

2

*

12

*

1

d

FF

d

dttjtfFdt

d

tjFtfdttftf

( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−=

π

ω

ωω

2

exp

*

2

*

2

d

tjFtf

If s (t) is real, than s (t) = s*(t) and

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

=== ωω

π

dSdttsdttsEs

222

2

1

:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-28-320.jpg)

![29

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Energy (continue – 1) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

=== ωω

π

dSdttsdttsEs

222

2

1

:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

−−−+−−−+

−−−−+−−

=

−−+−−−+−=

−

−−

00

0000

0

*

0

*2

00

0

*

00

*

0

00

*

0

*

0

*

4

1

4

1

ϕϕ

ϕϕϕϕ

ωωωωωωωω

ωωωωωωωω

ωωωωωωωωωω

jj

jjjj

eGGeGG

GGGG

eGeGeGeGSS

For finite band (W << ω0 ) signals (see Figure)

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫

∫∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

+∞

∞−

−

+∞

∞−

=−−−−=−−

≈−−−=−−−

ωωωωωωωωωωωωω

ωωωωωωωωωω ϕϕ

dGGdGGdGG

deGGdeGG jj

*

0

*

00

*

0

2

0

*

0

*2

00 000

( ) ( ) gs EdGdSE

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

:

22

=≈= ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

ωω

π

ωω

π

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-29-320.jpg)

![30

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Complex and Analytic Signals

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

We have the following definitions:

Real signal

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtj

etgetgts 00 *

2

1 ωω −

+=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tj

QI etatsjtstg θ

=+=: Envelope of the signal

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) tj

etgtjtjtats 0

0exp: ω

θω =+= Complex Signal

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtj

etgetgts 00 *

2

1 ωω −

+= ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]0

*

0

2

1

ωωωωω −−+−= GGS-1

F

F

( ) ( ){ } ( ){ } ( )0

0

ωωω ω

−=== GetgtsS tj

FF

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )ωω

ω

ωω

ωωω SU

S

GS 2

00

02

0 =

<

>

≈−=

For Band limited signals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-30-320.jpg)

![31

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Complex and Analytic Signals (continue – 1)

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) tj

etgtjtjtats 0

0exp: ω

θω =+=

Complex Signal

( ) ( ){ } ( ){ } ( )0

0

ωωω ω

−=== GetgtsS tj

FF

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )ωω

ω

ωω

ωωω SU

S

GS 2

00

02

0 =

<

>

≈−=

For Band limited signals

Analytic Signal

The Analytic Signal is a Complex Signal chosen that its spectrum if forced to be zero for ω<0.

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )ωωωωω SsignSUS +== 12:

~

( )

<−

=

>+

=

01

00

01

:

ω

ω

ω

ωsign

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )

t

j

tsignU

π

δωω +=+= −−

12 11

FF

The time function corresponding to the product of the spectrums of two time functions is

given by the time convolution of the two functions

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

−−

−

+=

−

+−=== ξ

ξ

ξ

π

ξ

ξπ

ξδξωωω d

t

sj

tsd

t

j

tsSUS 2

~~ 11

FFts](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-31-320.jpg)

![32

RADAR SignalsSOLO

Analytic Signal

The Analytic Signal is a Complex Signal chosen that its spectrum if forced to be zero for ω<0.

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

−−

−

+=

−

+−=== ξ

ξ

ξ

π

ξ

ξπ

ξδξωωω d

t

sj

tsd

t

j

tsSUS 2

~~ 11

FFts

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tsjtsd

t

sj

ts ˆ~ +=

−

+= ∫

+∞

∞−

ξ

ξ

ξ

π

ts

or

Complex and Analytic Signals (continue – 2)

From ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )ωωωωω SjSSsignS ˆ1:

~

+=+=

we have

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

<+

=

>−

=−=

0

00

0

ˆ

ωω

ω

ωω

ωωω

Sj

Sj

SsignjS

Assuming a Band Limited signal we can assume that

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tsjtststsSUSS ˆ~2

~

+=≈⇒=≈ ωωωω

where is the Hilbert Transform of s (t)( ) ( )

∫

+∞

∞−

−

= ξ

ξ

ξ

π

d

t

s

ts

1

:ˆ

(see “Hilbert Transformation” Presentation)

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-32-320.jpg)

![39

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

SOLO

Complex Representation of Bandpass Signals

The majority of radar signals are narrow band signals, whose Fourier transform is

limited to an angular-frequency bandwidth of W centered about a carrier angular

frequency of ±ω0.

Another form of s (t) is

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )ttstts

tttatttats

QI

tsts QI

00

00

sincos

sinsincoscos

ωω

ωθωθ

−=

−=

sI (t) – in phase component sQ (t) – quadrature component

1

2

Define the signal complex envelope: ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ]tjta

tjttatsjtstg QI

θ

θθ

exp

sincos:

=

+=+=

Therefore:

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]tstjtgts ReexpRe 0 == ω

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )tststjtgtjtgts *

2

1

2

1

exp

2

1

exp

2

1

00 +=−+= ∗

ωω

or:

3

4

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtjtats θω += 0exp

Analytic (complex) signal

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-39-320.jpg)

![40

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tttats θω += 0cos

SOLO

Autocorrelation

The Autocorrelation Function is extensively used in Radar Signal Processing

( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−= tdtstsRss ττ :

Real signalFor

The Autocorrelation Function is defined as:

Properties of the Autocorrelation Function:

2 ( ) ( )ττ ssss RR =−

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )ττττ

τ

ss

tt

ss RtdtststdtstsR =−=+=− ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+=+∞

∞−

'''

'

1 ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) sss EfdfSfStdtstsR === ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

*0 Es – signal energy

3

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )2222

2

2

0sss

EE

Inequality

Schwarz

ss REtdtstdtstdtstsR

ss

==−≤−= ∫∫∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

τττ

( ) ( )0ssss RR ≤τ

Autocorrelation is a mathematical tool for

finding specific patterns, such as the

presence of a known signal which has been

buried under noise.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-40-320.jpg)

![41

SOLO

Autocorrelation (continue – 1(

The Autocorrelation Function is extensively used in Radar Signal Processing

( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−= tdtgtgRgg ττ *:

Signal complex envelopeFor

The Autocorrelation Function is defined as:

Properties of the Autocorrelation Function:

2 ( ) ( )ττ *gggg RR =−

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )ττττ

τ

*''*'*

'

gg

tt

gg RtdtgtgtdtgtgR =−=+=− ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+=+∞

∞−

1 ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) sgg EfdfGfGtdtgtgR 2**0 === ∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

Es – signal energy

3

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )22

2

2

2

2

2

2

04** ggs

EE

Inequality

Schwarz

gg REtdtgtdtgtdtgtgR

ss

==−≤−= ∫∫∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

τττ

( ) ( )0gggg RR ≤τ

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtatg θexp:=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-41-320.jpg)

![42

SOLO

Autocorrelation (continue – 2(

The Autocorrelation Function is extensively used in Radar Signal Processing

( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−= tdtgtgRgg ττ *:

Signal complex envelopeFor

The Autocorrelation Function is defined as:

3

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

∫ ∫∫ ∫

∫ ∫

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

∞+

∞−

=

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

=

−−

∂

∂

==

∂

∂

=

0

11122

2

2

0

22211

1

1

0

212211

2

****

**00

gggg RR

gg

tdtgtgtdtg

t

tgtdtgtgtdtg

t

tg

tdtdtgtgtgtgR

τ

ττ

τ

τ

τ

( ) ( )0gggg RR ≤τ

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tjtatg θexp:=

(continue – 1)

Since Rgg (0) is a maximum of a continuous function at τ=0, we must have

( ) 00

2

==

∂

∂

τ

τ

ggR

Therefore ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 0** =

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

tdtg

t

tgtdtg

t

tg

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-42-320.jpg)

![48

Fourier Transform

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

−== dttjtftfF νπνπ 2exp:2 F

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

∞

=

−

+∞

−∞=

=

+=

0

* 21

n

nsT

n

eTnf

T

n

jsF

T

sF

π

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

== ννπνπνπ dtjFFtf 2exp2:2-1

F

SOLO

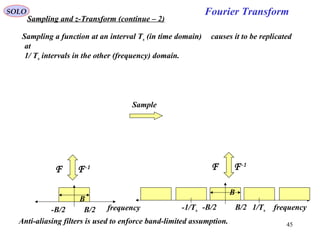

Sampling and z-Transform (continue – 5)

We found

Using the definition of the Fourier Transform and it’s inverse:

we obtain ( ) ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

= ννπνπ dTnjFTnf 2exp2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑∫∑

∞

=

+∞

∞−

∞

=

−=−=

0

111

0

*

exp2exp2exp

nn

n

sTndTnjFsTTnfsF ννπνπ

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∫ ∑

+∞

∞−

+∞

−∞=

−−== 111

*

2exp22 νννπνπνπ dTnjFjsF

n

( ) ( ) ∑∫ ∑

+∞

−∞=

+∞

∞−

+∞

−∞=

−=

−−==

nn T

n

F

T

d

T

n

T

FjsF νπνννδνπνπ 2

11

22 111

*

We recovered (with –n instead of n) ( ) ∑

+∞

−∞=

+=

n T

n

jsF

T

sF

π21*

Second Way (continue)

Making use of the identity: with 1/T instead of T

and ν - ν 1 instead of t we obtain: ( )[ ] ∑∑

−−=−−

nn T

n

T

Tnj 11

1

2exp ννδννπ

( )∑∑ −=

−

nn

TntT

T

tn

j δπ2exp

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-48-320.jpg)

![54

Fourier TransformSOLO

The Discrete Time Fourier Transform (DTFT) (continue-1)

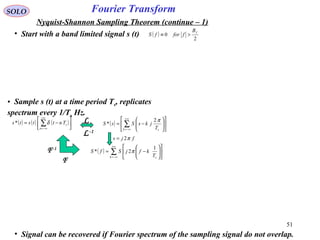

• Signal can be recovered if Fourier spectrum of the sampling signal do not overlap.

Discretization of a Continuous Signal ( ) ( )∫

+∞

∞−

== fdefSTnts sTnfj

s

π2

DTFT-1

DTF

T

Discrete Time Fourier Transform

(DTFT)

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

∞+

−∞=

−

=

∞+

−∞=

−

==

n

n

f

f

j

s

T

f

n

Tnfj

sDTFT

s

s

s

s

eTnseTnsfS

π

π

2

1

2

:

We can see that

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

∞+

−∞=

−

−∞+

−∞=

+

−

===+

n

DTFT

nkj

n

f

f

j

s

n

n

f

fkf

j

ssDTFT fSeeTnseTnsfkfS ss

s

1

2

22

π

ππ

The Discrete Time Fourier Transform SDTFT (fs) is periodic with period fs.

Let compute

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( )∑ ∑

∑ ∫∫ ∑∫

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

=←

≠←

+

−

−

∞+

−∞=

+

−

−

+

−

∞+

−∞=

−

+

−

=

−

−

=

−

=

==

n

s

sn

nm

nm

ss

f

fs

nm

f

f

j

s

n

f

f

nm

f

f

j

s

f

f n

nm

f

f

j

s

f

f

m

f

f

j

DTFT

Tms

Tnm

nm

fTns

f

nm

j

e

Tns

fdeTnsdfeTnsdfefS

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

1sin

2

1

0

2/

2/

2

2/

2/

22/

2/

22/

2/

2

π

π

π

π

πππ

( ) ( )∑

+∞

−∞=

−

=

n

Tnfj

sDTFT

s

eTnsfS π2

: ( ) ( )

( )

( )

∫

+

−

=

s

s

s

T

T

nTfj

DTFTss dfefSTTns

2/1

2/1

2π](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-54-320.jpg)

![55

Fourier TransformSOLO

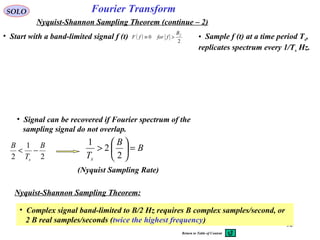

The Discrete Time Fourier Transform (DTFT) (continue-2)

Normalization of the frequency

DTFT-1

DTFT

( ) ( )∑

+∞

−∞=

−

=

n

Tnfj

sDTFT

s

eTnsfS π2

: ( ) ( )

( )

( )

∫

+

−

=

s

s

s

T

T

nTfj

DTFTss dfefSTTns

2/1

2/1

2π

( ) ( )[ ]

[ ]2/1,2/1

2/1,2/1

:

*

*

+−∈

+−∈

=

f

TTf

Tff

ss

s

( ) ( )∑

+∞

−∞=

−

=

n

nfj

DTFT ensfS *2*

: π

DTFT-1

DTFT

( ) ( )∫

+

−

=

2/1

2/1

*2

** dfefSns nfj

DTFT

π

Example ( ) 1,,1,002

−== −

NneAns nfj

π

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )[ ]

( )( )1*

0

0

*

*

**

**

*2

*21

0

*2*

0

0

0

00

00

0

0

0

*sin

*sin

1

1

−−−

−−

−−

−−−

−−−

−−

−−−

=

−−

−

−

=

−

−

=

−

−

== ∑

Nffj

ffj

Nffj

ffjffj

NffjNffj

ffj

NffjN

n

nffj

DTFT

e

ff

Nff

A

e

e

ee

ee

A

e

e

AeAfS

π

π

π

ππ

ππ

π

π

π

π

π

|SDTFT(f*)|

Normalized Frequency](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-55-320.jpg)

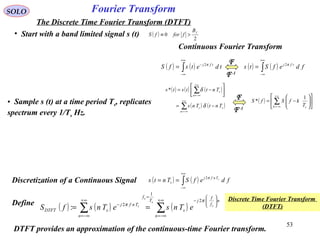

![57

Fourier Transform

( ) ( )∑

−

=

−

=

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT eTnskS

π

SOLO

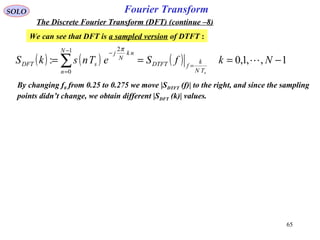

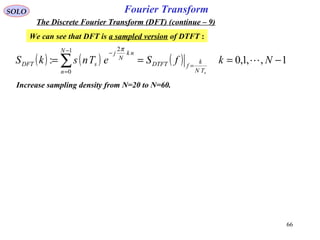

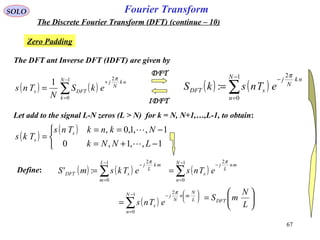

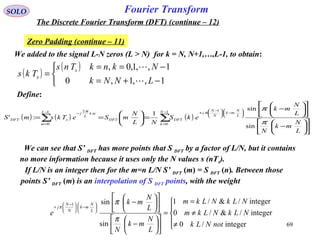

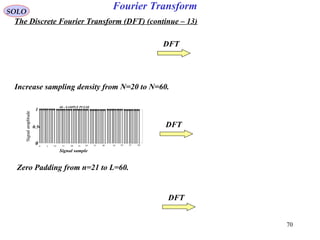

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)

Assume a periodic sequence, sampled at a time period Ts, such that s (n Ts) = s [(n+kN) Ts]

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) requires an input function that is discrete

and whose non-zero values have a limited (finite) duration.

Unlike the Discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT), it only evaluates enough frequency

components to reconstruct the finite segment that was analyzed. Its inverse transform

cannot reproduce the entire time domain, unless the input happens to be periodic (forever).

Therefore it is often said that the DFT is a transform for Fourier analysis of finite-domain

discrete-time functions

For the sequence s (0), s (Ts),…,s [(N-1) Ts] we define the Discrete Fourier Transform:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-57-320.jpg)

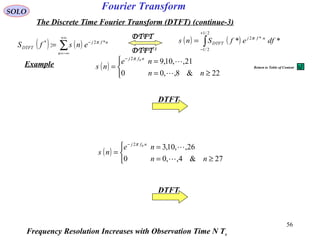

![58

Fourier Transform

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

−

=

−

=

−

==

1

0

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

s

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT WTnseTnskS

π

SOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 1)

For the sequence s (0), s (Ts),…,s [(N-1) Ts] we define the Discrete Fourier Transform:

where is a primitive N'th root of unity

and is periodic

N

j

eW

π2

:

−

=

n

Nm

N

j

n

N

j

Nmn

N

j

Nmn

WeeeW =

=

=

−−

+

−

+

1

222 πππ

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )[ ]

N

N

N s

s

s

s

s

s

W

NNNNNNN

NNNNNNN

NN

NN

NN

S

DFT

DFT

DFT

DFT

DFT

TNs

TNs

Ts

Ts

Ts

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

NS

NS

S

S

S

⋅−

⋅−

⋅

⋅

⋅

=

−

−

−−−−−−−

−−−−−−−

−−

−−

−−

1

2

2

1

0

1

2

2

1

0

1121211101

1222221202

1222221202

1121211101

1020201000

[ ] NNN sWS = [ ]NW is a Vandermonde type of Matrix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-58-320.jpg)

![59

Fourier TransformSOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 2)

nNmn

WW =+

[ ] [ ] N

H

NN I

N

WW

1

=

N

j

eW

π2

−

= 1

2

* −

== WeW N

j

π

[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

=

−−−−−−−

−−−−−−−

−−

−−

−−

1121211101

1222221202

1222221202

1121211101

1020201000

NNNNNNN

NNNNNNN

NN

NN

NN

N

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

W

[ ] [ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

==

−+−−+−−−−−−

−+−−+−−−−−−

+−+−−−

+−+−−−

+−+−−−

1112121110

2122222120

2122222120

1112121110

0102020100

*

NNNNNNN

NNNNNNN

NN

NN

NN

T

N

H

N

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WW

Let multiply those two matrices

[ ] [ ]( )( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

=

≠=

−

−

=

−

−

==

+++++=

−

−

−

−−

=

−

+−−−−

∑

mkN

mk

W

W

W

W

W

WWWWWWWWWW

mk

mk

N

mk

NmkN

j

jmk

mNNkmjjkmkmk

mk

H

NN

0

1

1

1

1

1

1

0

111100

,

Where IN is the N x N identity matrix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-59-320.jpg)

![60

Fourier Transform

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

−

=

−

=

−

==

1

0

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

s

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT WTnseTnskS

π

SOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 3)

For the sequence s (0), s (Ts),…,s [(N-1) Ts] we defined the Discrete Fourier Transform:

[ ] NNN sWS = [ ]NW is a Vandermonde type of Matrix

We found that

[ ] [ ] N

H

NN I

N

WW

1

= Where IN is the NxN identity matrix

Therefore the Inverse Discrete Fourier Transform (IDFT) is

[ ] N

H

NN SW

N

s

1

=

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

−

=

−

=

−

==

1

0

21

0

11 N

n

nk

N

j

DFT

N

k

nk

DFTs ekS

N

WkS

N

Tns

π

D.F.T.

I.D.F.T.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-60-320.jpg)

![61

Fourier TransformSOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 4)

Second way to find the Inverse Discrete Fourier Transform (IDFT). Let compute:

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

∑ ∑∑∑∑

−

=

−

=

−−−

=

−

=

−−−

=

+

==

1

0

1

0

21

0

1

0

21

0

2 N

n

N

k

rnk

N

j

s

N

k

N

n

rnk

N

j

s

N

k

rk

N

j

DFT eTnseTnsekS

πππ

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( ) ( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( ) ( )

( )[ ]

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( ) ( )

≠−

=−

=

−+

−

−+−

−

−

−

−

=

−+

−

−+−

−

−

=

−+

−−

−+−−

=

−

−

=

−

−

=

−−

−−

−−

−−

−

=

−−

∑

Nmrn

NmrnN

rn

N

jrn

N

rnjrn

rn

N

rn

N

rn

rn

N

rn

N

jrn

N

rnjrn

rn

N

rn

rn

N

jrn

N

rnjrn

e

e

e

e

e

rn

N

j

rnj

rn

N

j

N

rn

N

j

N

k

rnk

N

j

0

cossin

cossin

sin

sin

cossin

cossin

sin

sin

2

sin

2

cos1

2sin2cos1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

1

0

2

ππ

ππ

π

π

π

π

ππ

ππ

π

π

ππ

ππ

π

π

π

π

π

( ) ( )[ ] ,2,1,0

1

0

2

±±=+=∑

−

=

+

mTmNrsNekS s

N

k

rk

N

j

DFT

π](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-61-320.jpg)

![62

Fourier Transform

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

−

=

−

=

−

==

1

0

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

s

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT WTnseTnskS

π

SOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 5)

For the sequence s (0), s (Ts),…,s [(N-1) Ts] we define the Discrete Fourier Transform:

where is a primitive N'th root of unity

and is periodic

N

j

eW

π2

:

−

=

n

Nm

N

j

n

N

j

Nmn

N

j

Nmn

WeeeW =

=

=

−−

+

−

+

1

222 πππ

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )[ ]

⋅−

⋅−

⋅

⋅

⋅

=

−

−

−−

−−

−−

−−

s

s

s

s

s

NN

NN

NN

NN

DFT

DFT

DFT

DFT

DFT

TNs

TNs

Ts

Ts

Ts

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

WWWWW

NS

NS

S

S

S

1

2

2

1

0

1

2

2

1

0

12210

23320

23420

12210

00000

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-62-320.jpg)

![63

Fourier TransformSOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 6)

The DFT ant Inverse DFT (IDFT) are given by

( ) ( )∑

−

=

+

=

1

0

2

1 N

k

nk

N

j

DFTs ekS

N

Tns

π

( ) ( )∑

−

=

−

=

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT eTnskS

π

IDFT

DFT

with the periodic properties

( )[ ] ( )

,2,1,0 ±±=

=+

m

TnsTmNns ss

( ) ( )

,2,1,0 ±±=

=+

m

kSNmkS DFTDFT

The sequence s (0), s (Ts),…,s [(N-1) Ts] can be interpreted to be a sequence of finite

length, given for r = 0, 1,…,N-1, and zero otherwise or a periodic sequence, defined

for all r.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-63-320.jpg)

![64

Fourier Transform

( ) ( )∑

−

=

−

=

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT eTnskS

π

SOLO

The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 7)

The DFT ant Inverse DFT (IDFT) are given by

( ) ( )∑

−

=

+

=

1

0

2

1 N

k

nk

N

j

DFTs ekS

N

Tns

π

IDFT

DFT

( ) ( )∑

+∞

−∞=

−

=

n

nfj

DTFT ensfS *2*

: π

( ) ( )∫

+

−

=

2/1

2/1

*2

** dfefSns nfj

DTFT

π

IDTFT

DTFT

The DTFT ant Inverse DTFT (IDTFT) where given by

We can see that DFT is a sampled version of DTFT by tacking:

( ) ( )[ ]

[ ]2/1,2/1

2/1,2/1

1,,1,0

*

*

+−∈

+−∈

−==⇒==

f

TTf

Nk

TN

k

f

N

k

fTf

ss

s

s

( ) ( ) ( ) 1,,1,0:

1

0

2

−=== =

−

=

−

∑ NkfSeTnskS

sTN

k

fDTFT

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT

π](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-64-320.jpg)

![72

SOLO

Properties of The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 14)

( )mns − ( )

mk

N

j

DFT ekS

π2

−

Linearity1 ( ) ( )nsns 2211 αα +

Shift of a Sequence2

3

4

5

Periodic Convolution

6

7

Conjugate

8

9

IDFT

DFT ( ) ( )∑

−

=

−

=

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

N

j

DFT enskS

π

( ) ( )∑

−

=

+

=

1

0

2

1 N

k

nk

N

j

DFT ekS

N

ns

π

( ) ( )kSkS DFTDFT 2211 αα +

( ) ( )nsns 21 , Periodic Sequence

(Period N)

( ) ( )kSkS DFTDFT 21 , DFT

(Period N)

( )

nl

N

j

ens

π2

−

( )lkSDFT −

( ) ( )∑

−

=

−⋅

1

0

21

N

m

mnsms

( ) ( )kSkS DFTDFT 21 ⋅

( ) ( )nsns 21 ⋅

( ) ( )∑

−

=

−⋅

1

0

21

1 N

l

DFTDFT lkSlS

N

( )ns∗

( )kSDFT −

∗

( )ns −∗

( )kSDFT

∗

Real & Imaginary ( )[ ]nsRe

( )[ ]nsImj

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] 2/kSkSkS DFTDFTeven −+=

∗

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] 2/kSkSkS DFTDFTodd −−=

∗](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-72-320.jpg)

![73

SOLO

Properties of The Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) (continue – 15)

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] 2/: nsnsnseven −+= ∗

( )kSDFTReEven Part10

11

12 Symmetric Proprties

(only when s (n) is real)

IDFT

DFT ( ) ( )∑

−

=

−

=

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

N

j

DFT enskS

π

( ) ( )∑

−

=

+

=

1

0

2

1 N

k

nk

N

j

DFT ekS

N

ns

π

( ) ( )nsns 21 , Periodic Sequence

(Period N)

( ) ( )kSkS DFTDFT 21 , DFT

(Period N)

( )lkSDFT −

( ) ( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

−−∠=∠

−=

−−=

−=

−=

∗

kSkS

kSkS

kSmkSm

kSkS

kSkS

DFTDFT

DFTDFT

DFTDFT

DFTDFT

DFTDFT

II

ReRe

Odd Part ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] 2/: nsnsnsodd −−= ∗

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-73-320.jpg)

![75

Fourier TransformSOLO

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

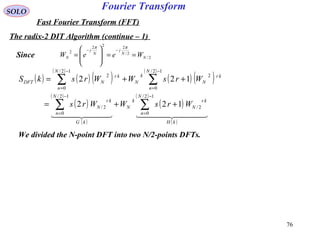

The radix-2 DIT Algorithm

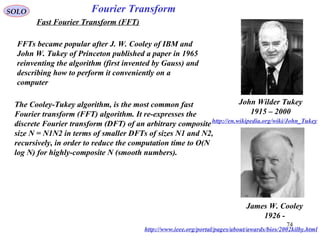

The radix-2 decimation-in-time (DIT) FFT is the simplest and most common form of the

Cooley-Tukey algorithm, although highly optimized Cooley-Tukey implementations

typically use other forms of the algorithm as described below. Radix-2 DIT divides a DFT

of size N into two interleaved DFTs (hence the name "radix-2") of size N/2 with each

recursive stage.

( ) ( ) ( )∑∑

−

=

−

=

−

==

1

0

1

0

2

:

N

n

nk

s

N

n

nk

N

j

sDFT WTnseTnskS

π

For the sequence s (0), s (Ts),…,s [(N-1) Ts] we define the Discrete Fourier Transform:

1,1, 22/1

2

*

2

+==−====→= −−−

−

ππ

ππ

jNj

evenN

NN

j

N

j

eWeWWeWeW

Suppose N is a power of 2; i.e. N=2L

(L is integer). Since N is a even integer, let compute

SDFT (k) by separate s (nTs) into two (N/2)-point sequences consisting of the even-numbered

points (n=2r) and odd numbered points (n=2r+1).

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

∑∑

∑∑

−

=

−

=

−

=

+

−

=

++=

++=

12/

0

2

12/

0

2

12/

0

12

12/

0

2

122

122

N

n

kr

N

k

N

N

n

kr

N

N

n

kr

N

N

n

kr

NDFT

WrsWWrs

WrsWrskS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-75-320.jpg)

![79

Fourier TransformSOLO

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

The radix-2 DIT Algorithm (continue – 2)

( ) ( )kkj

kN

N

j

Nk

N eeW 1

2

2/

−==

= −

−

π

π

We divided the N-point DFT into two N/2-points DFTs.

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )

∑∑

−

=

−

−

=

+

++=++=

12/

0

1

2/

12/

0

2/

2/2/

N

n

kn

N

Nk

N

N

n

Nnk

N

kn

NDFT WWNnsnsWNnsWnskS

k

Since N/2 is an even integer (N=2L

)

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

tgofFFTN

N

n

nl

N

WW

N

N

n

nl

N

ng

DFT WngWNnsnslkS

NN

L

2/

12/

0

2/

2

12/

0

2

2/

2

2/2 ∑∑

−

=

=

=

−

=

=++==

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

thofFFTN

N

n

nl

N

WW

N

N

n

nl

N

nh

n

NDFT WnhWWNnsnslkS

NN

L

2/

12/

0

2/

2

12/

0

2

2/

2

2/12 ∑∑

−

=

=

=

−

=

=+−=+=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-79-320.jpg)

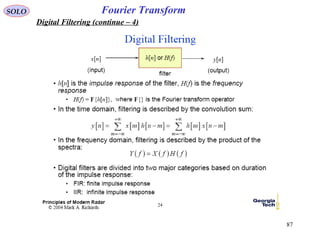

![83

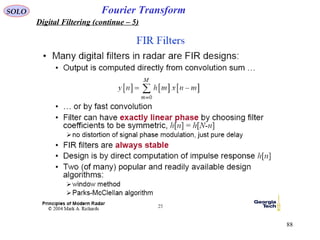

Fourier TransformSOLO

Digital Filtering

Digital Filters can be partitioned in two distinct classes:

• Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters that have an impulse response

h (nT) of finite duration

( )

( )

≥<

−=

=

Nnn

Nnnh

Tnh

&,00

1,,1,0

• Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filters that have an impulse response

h (nT) of infinite duration

If s (n) is an input signal to the digital filter, then the output of the digital filter

y (k) is related to the input by a relation of the type:

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( )[ ]TMkybTkyb

TNksaTksaTksaTky

M

N

−−−−−

−++−+=

1

1

1

10

If all the coefficients ai, bi are constants we can use the z transform to obtain:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )zSzHzS

zbzb

zazaa

zY M

M

N

N

⋅=⋅

+++

+++

= −−

−−

1

1

1

10

1

For a causal filter N ≤ M.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-83-320.jpg)

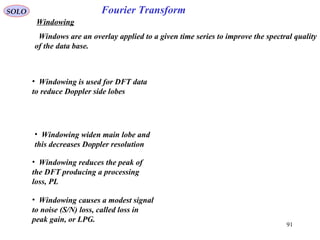

![92

Fourier TransformSOLO

Windowing

Rectangular [ ]

≤≤

=

otherwise

Mn

nw

,0

0,1

Bartlett

(triangular) [ ]

≤<−

≤≤

=

otherwise

MnMMn

MnMn

nw

,0

2/,/22

2/0,/2

Hanning

Hammming

[ ]

( )

≤≤−

=

otherwise

MnMn

nw

,0

0,/2cos5.05.0 π

[ ]

( )

≤≤−

=

otherwise

MnMn

nw

,0

0,/2cos46.054.0 π

Blackman [ ]

( ) ( )

≤≤+−

=

otherwise

MnMnMn

nw

,0

0,/4sin08.0/2cos5.042.0 ππ

Julius Ferdinand von Hann (1839 -1921)

Richard Wesley Hamming (1915 –1998)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-92-320.jpg)

![93

Fourier TransformSOLO

Windowing (continue – 1)

cosine

[ ]

≤≤<

−

−

=

otherwise

Mn

M

Mn

nw

,0

0&5.0

2/

2/

2

1

exp

2

σ

σ

Lanczos

[ ]

≤≤

−

=

otherwise

Mn

M

n

nw

,0

0,1

2

sinc

Gauss

[ ]

≤≤

=

−

=

otherwise

Mn

M

n

M

n

nw

,0

0,sin

2

cos

πππ

[ ]

( )

≤≤

−−

=

otherwise

Mn

I

M

n

I

nw

,0

0,

1

2

1

0

2

0

α

α

Kaiser

α=2π

α=3π](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-93-320.jpg)

![95

Fourier TransformSOLO

Windowing (continue – 3)

Dolph-Chebyshev window

( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ]

( ) ( )4,3,2,10cosh

1

cosh

1,,2,1,0,

coshcosh

coscoscos

1

1

1

≈

=

−=

=

=

−

−

−

αβ

β

π

β

ω

ω

α

N

Nk

N

N

k

N

W

WIDFTnw

k

k

The α parameter controls the side-lobe level via the formula:

Side-Lobe Level in dB = - 20 α

The Dolph-Chebyshev Window (or Dolph window) minimizes the Chebyshev norm of

the side lobes for a given main lobe width 2 ωc:

( ) ( ){ }ωωω WWsidelobes cwwww >=∞= ∑

=

∑

maxmin:min 1,1,

The Chebyshev norm is also called the L - infinity norm, uniform norm, minimax

norm, or simply the maximum absolute value.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-95-320.jpg)

![109

SOLO Coherent Pulse Doppler Radar

An idealized target doppler response will

provide at IF Amplifier output the signal:

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ]tjtj

dIFIF

dIFdIF

ee

A

tAts ωωωω

ωω +−+

+=+=

2

cos

that has the spectrum:

f

fIF+fd

-fIF-fd

-fIF fIF

A2

/4A2

/4 |s|2

0

Because we used N coherent pulses of

width τ and with Pulse Repetition Time T

the spectrum at the IF Amplifier output

f

-fd fd

A2

/4A2

/4

|s|2

0

After the mixer and base-band filter:

( ) ( ) [ ]tjtj

dd

dd

ee

A

tAts ωω

ω −

+==

2

cos

We can not distinguish between

positive to negative doppler!!!

and after the mixer :](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-109-320.jpg)

![110

SOLO Coherent Pulse Doppler Radar

We can not distinguish

between positive to negative

doppler!!!

Split IF Signal:

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ]tjtj

dIFIF

dIFdIF

ee

A

tAts ωωωω

ωω +−+

+=+=

2

cos

( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ]t

A

ts

t

A

ts

dIFQ

dIFI

ωω

ωω

+=

+=

sin

2

cos

2

Define a New Complex Signal:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tj

QI

dIF

e

A

tsjtstg ωω +

=+=

2

f

fIF+fd

fIF

A2

/2|g|2

0

f

fd

A2

/2

|s|2

0

Combining the signals after the mixers

( ) tj

d

d

e

A

tg ω

2

=

We now can distinguish

between positive to negative

doppler!!!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-110-320.jpg)

![111

SOLO Coherent Pulse Doppler Radar

Split IF Signal:

( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ]t

A

ts

t

A

ts

dIFQ

dIFI

ωω

ωω

+=

+=

sin

2

cos

2

Define a New Complex Signal:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]tj

QI

dIF

e

A

tsjtstg ωω +

=+=

2

f

fd

A2

/2

|s|2

0

Combining the signals after the mixers

( ) tj

d

d

e

A

tg ω

2

=

We now can distinguish

between positive to negative

doppler!!!

From the Figure we can see that in this

case the doppler is unambiguous only if:

T

ff PRd

1

=<

Because we used N coherent pulses of

width τ and with Pulse Repetition Time T

the spectrum after the mixer output is

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-111-320.jpg)

![119

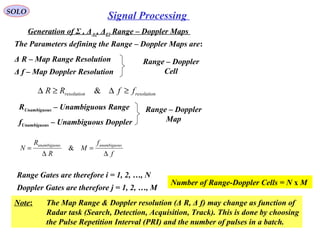

SOLO Signal Processing

Generation of Σ , ΔAz, ΔEl Range – Doppler Maps (continue – 1)

The received signal from the scatter k is:

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )ttTktttTkttfCts ddkdk

r

k

r

k ++≤≤++−= τθπ2cos

Ck

r

– amplitude of received signal

td (t) – round trip delay time given by ( )

2/c

tRR

tt kk

d

+

=

θk – relative phase

The received signal is down-converted to base-band in order to extract the quadrature

components. More precisely sk

r

(t) is mixed with: ( ) [ ] τθπ +≤≤+= TktTktfCty kkk 2cos

After Low-Pass filtering the quadrature components of Σk, ΔAz k or ΔEl k signals are:

( ) ( )

( ) ( )

=

=

tAtx

tAtx

kkQk

kkIk

ψ

ψ

sin

cos

( ) ( )

+−≅−=

c

tR

c

R

fttft kk

kdkk

22

22 ππψ

The quadrature samples are given by:

( ) ( )

+−≅=

c

tR

c

R

fjAjAtX kk

kkkkk

22

2expexp πψ

Ak - amplitude of Σk, ΔAz k or ΔEl k signals

ψk - phase of Σk, ΔAz k or ΔEl k signals

( )

+−

+≅+=

c

tR

c

R

fAj

c

tR

c

R

fAxjxtX kk

kk

kk

kkQkIkk

22

2sin

22

2cos ππ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-119-320.jpg)

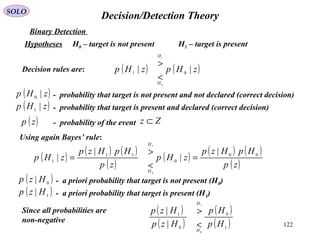

![130

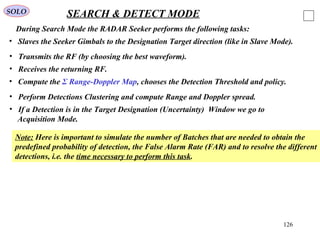

SOLO SEARCH & DETECT MODE

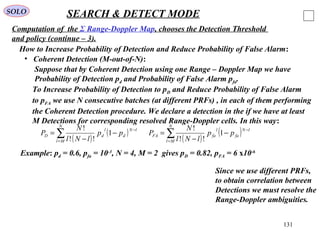

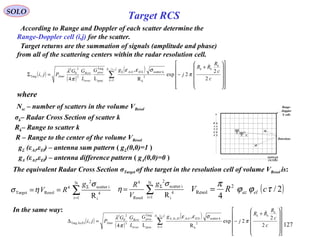

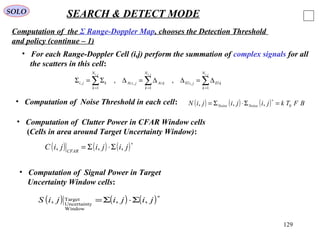

Computation of the Σ Range-Doppler Map, chooses the Detection Threshold

and policy (continue – 2).

DOPPLER

WINDOW

R W

A I

N N

G D

E O

W

R G

A A

N T

G E

E S

DOPPLER

FILTERS

S cells

CFAR

Window

R∆

f∆

Target

Uncertainty

Window

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∑

∗

+ Σ⋅Σ=

n

j Window

CFARNoiseClutter jiji

n

iC ,,

1

Guard

(Gap)

Window

• Computation of Clutter + Noise Threshold

• Coherent Detection:

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ClutterThjiNiCIf

ClutternoThjiNiCIf

NoiseClutter

NoiseClutter

⇒+>

⇒+≤

+

+

1,

1,

( ) NoiseThNjiS +≥

Window

yUncertaint

Target,

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∑

∗

+ Σ⋅Σ=

n

j Window

CFARNoiseClutter jiji

n

iC ,,

1

1. If no Clutter declare a Detection in the (i,j) cell of the Target Window if

ThNoise is chosen to assure a predefined

Probability of Detection pd and of False Alarm pFA

( ) NoiseClutterNoiseClutter ThCjiS ++ +≥

Window

yUncertaint

Target,

2. If Clutter declare a Detection in the (i,j) cell of the Target Window if

ThNoise is chosen to assure a predefined

Probability of Detection pd and of False Alarm pFA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-radarsignalprocessing-150117083950-conversion-gate01/85/1-radar-signal-processing-130-320.jpg)