This document discusses memory management techniques in computer architecture, including:

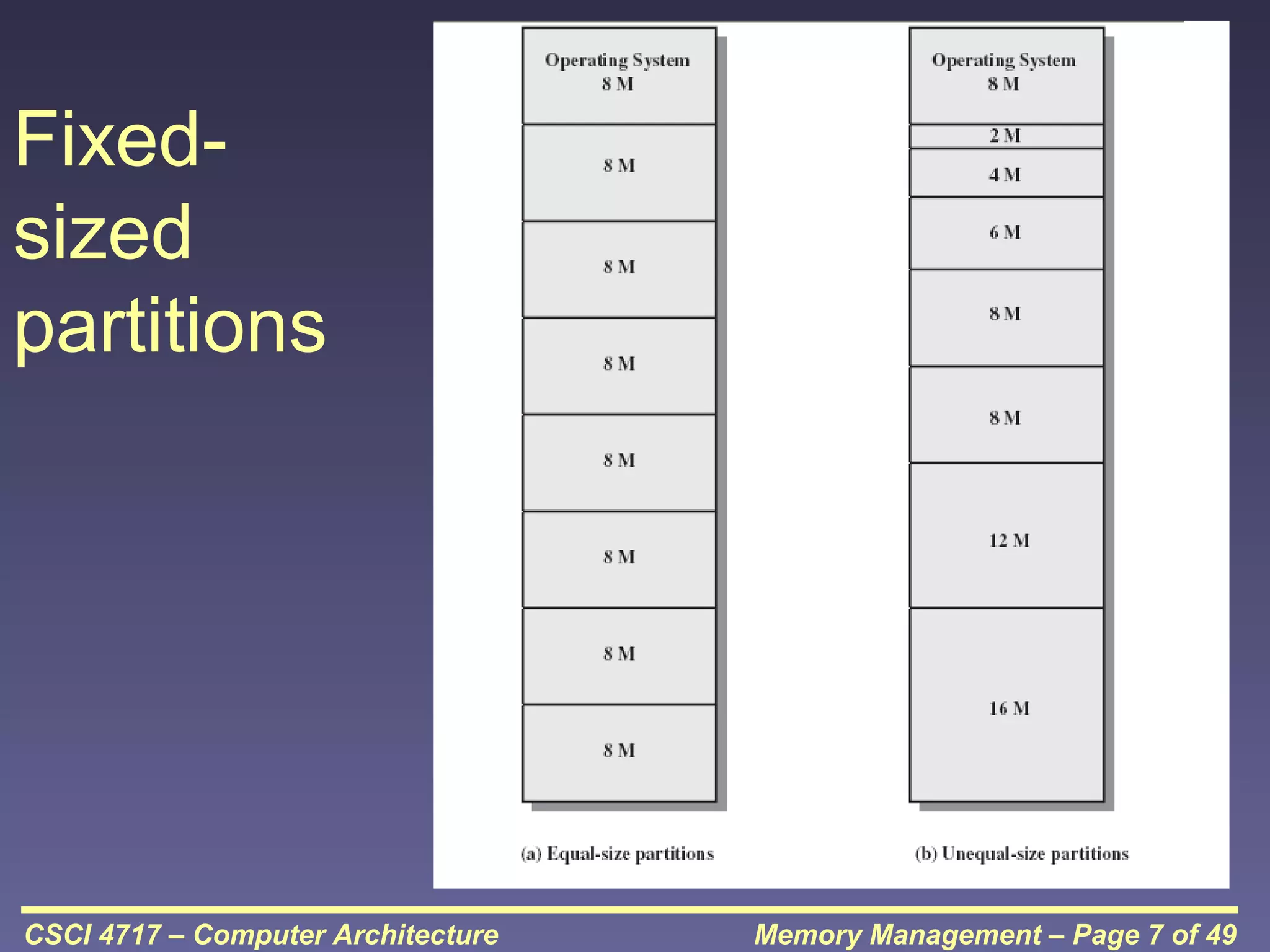

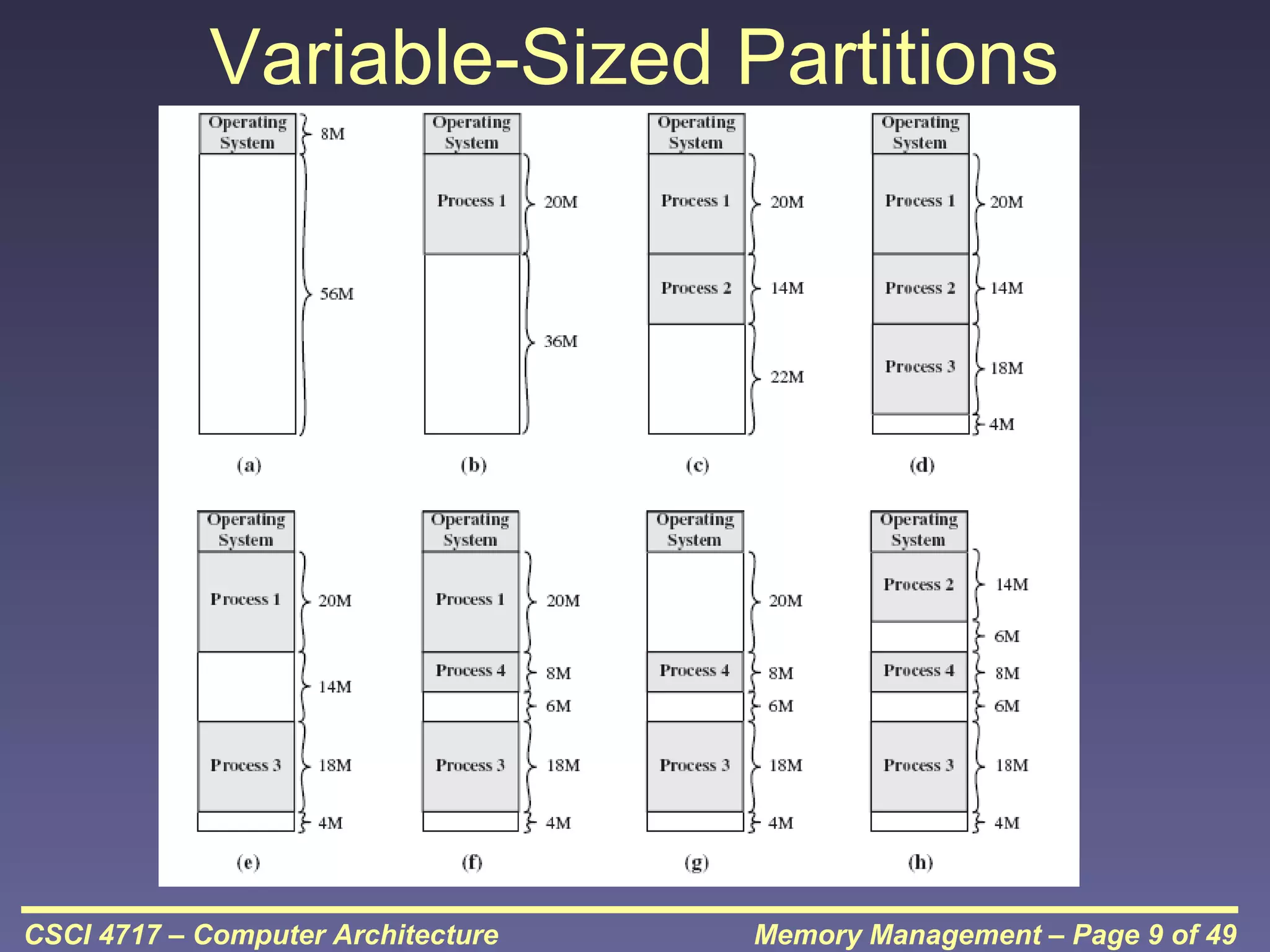

1) Memory is divided into partitions for the operating system and active processes in a uni-program system, while in a multi-program system memory is further subdivided and shared among active processes.

2) Swapping allows processes to exceed main memory size by storing inactive processes on disk and swapping them back into memory as needed, reducing idle CPU time from I/O waits.

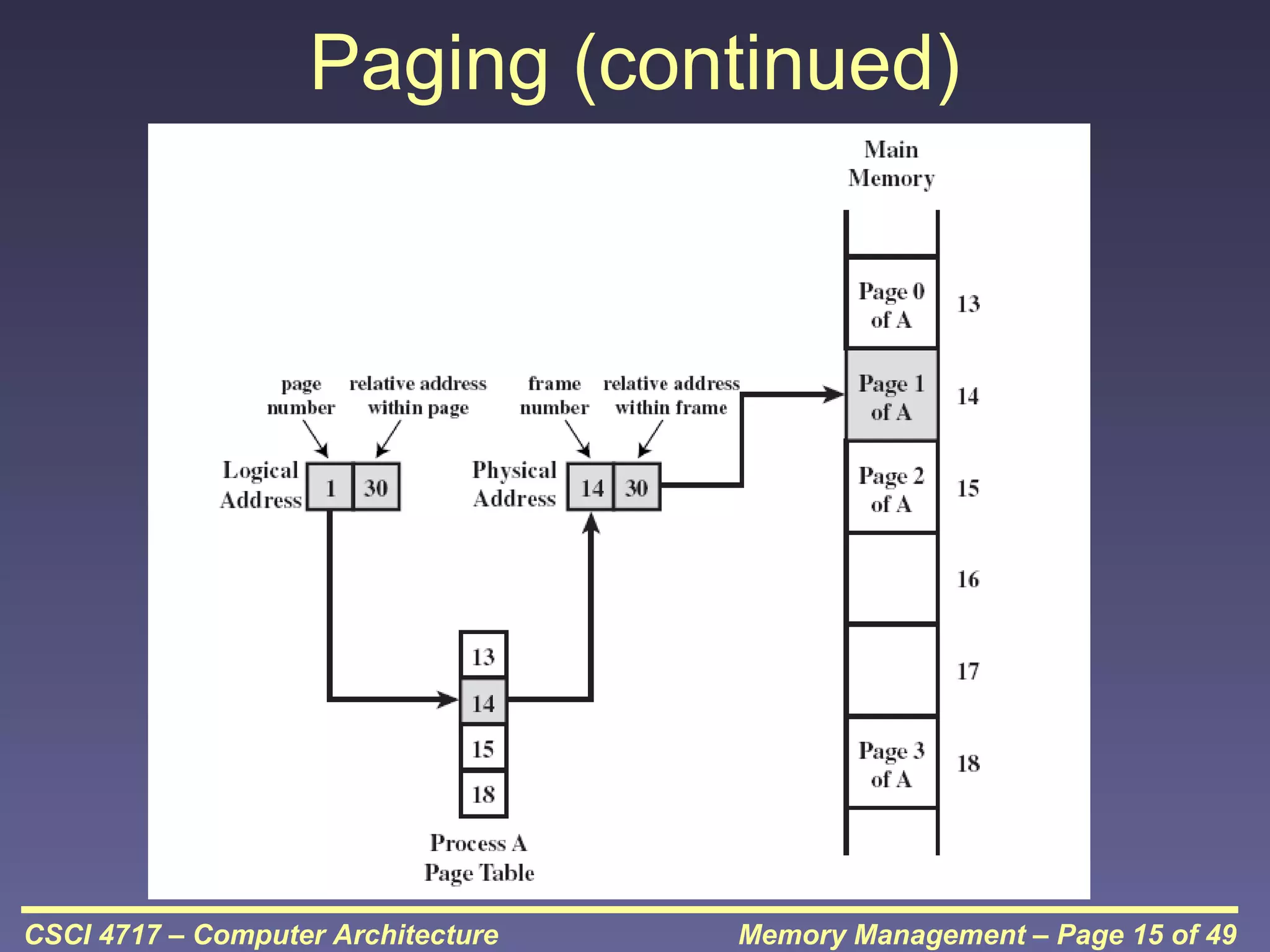

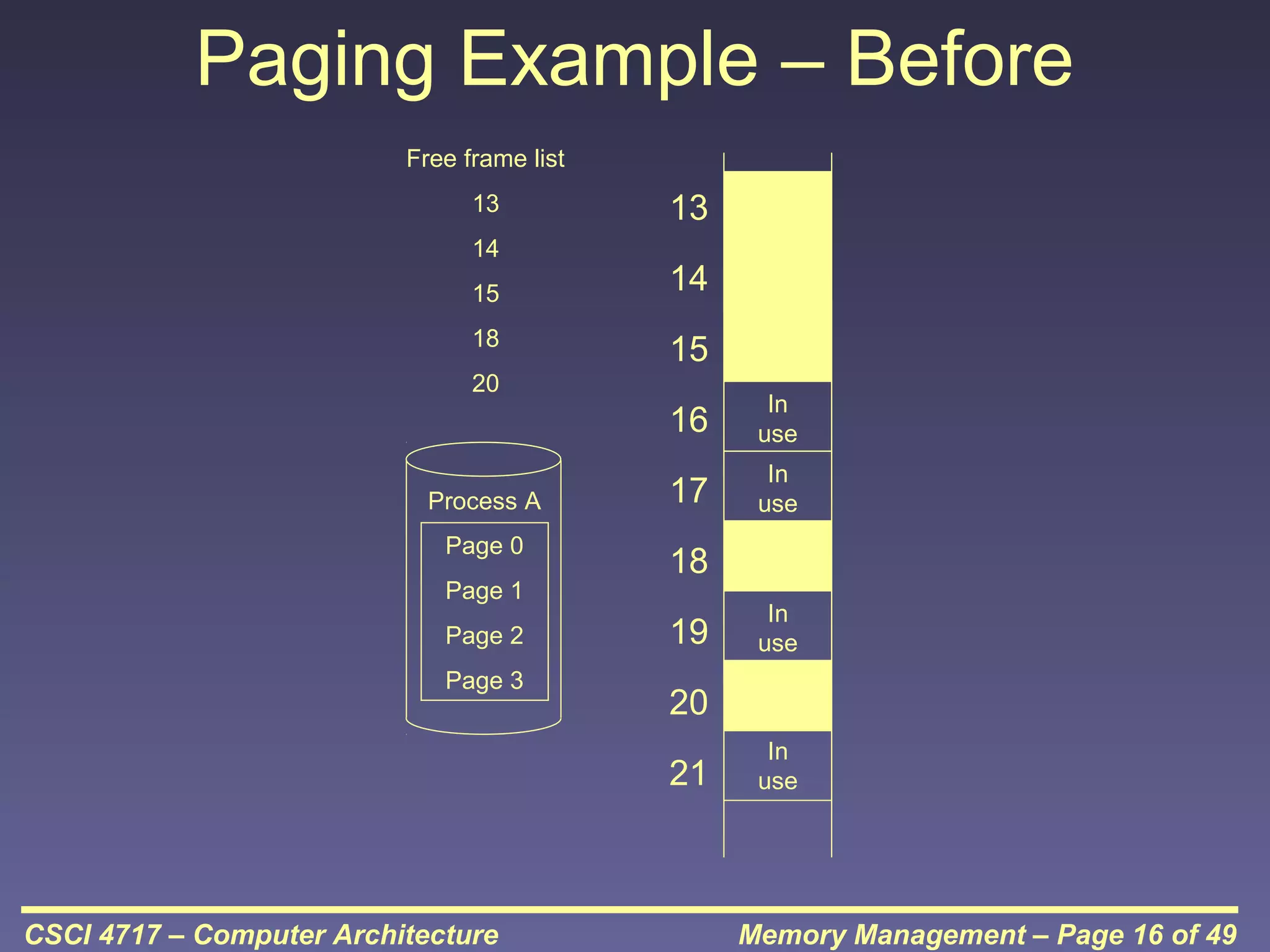

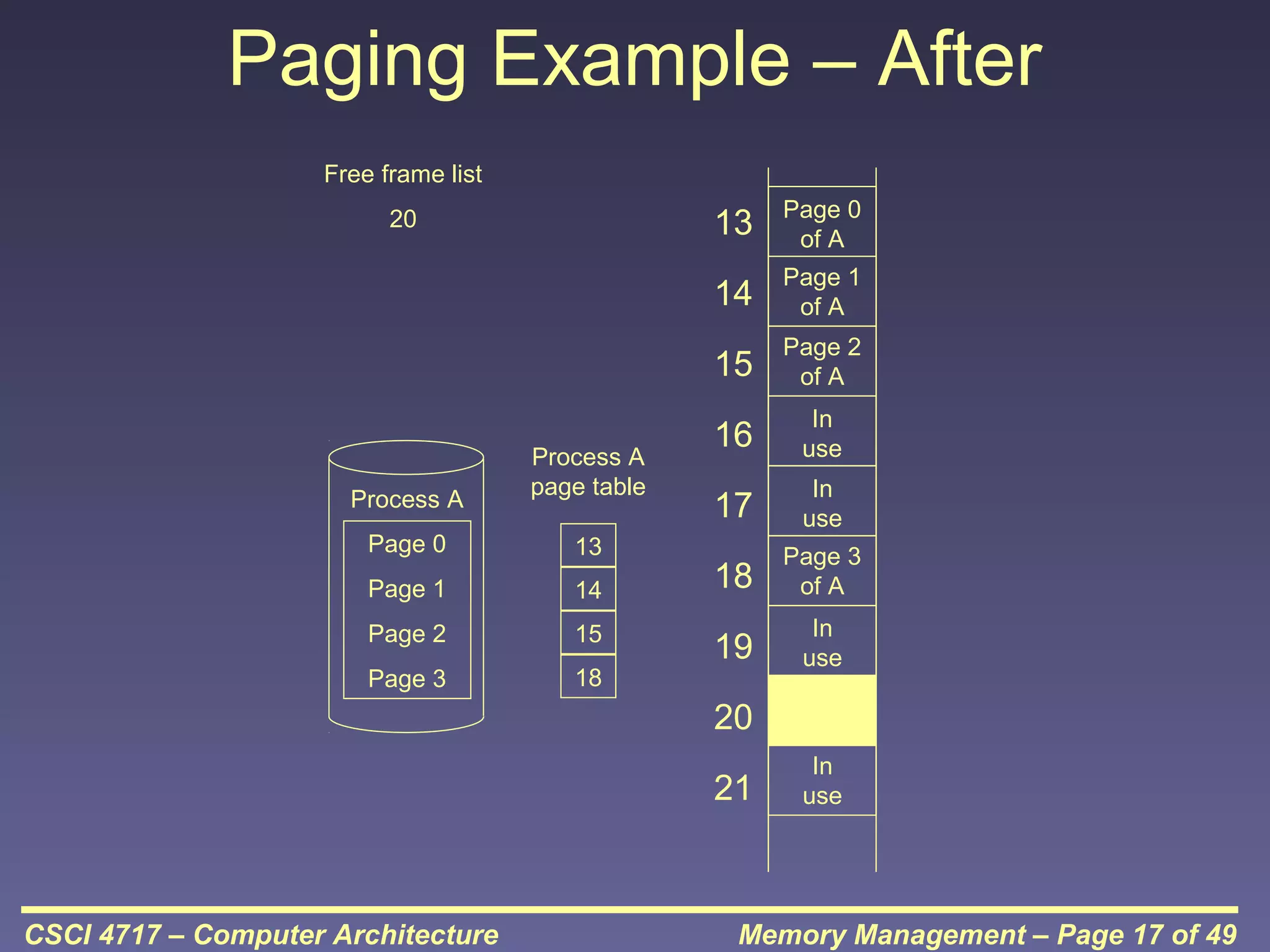

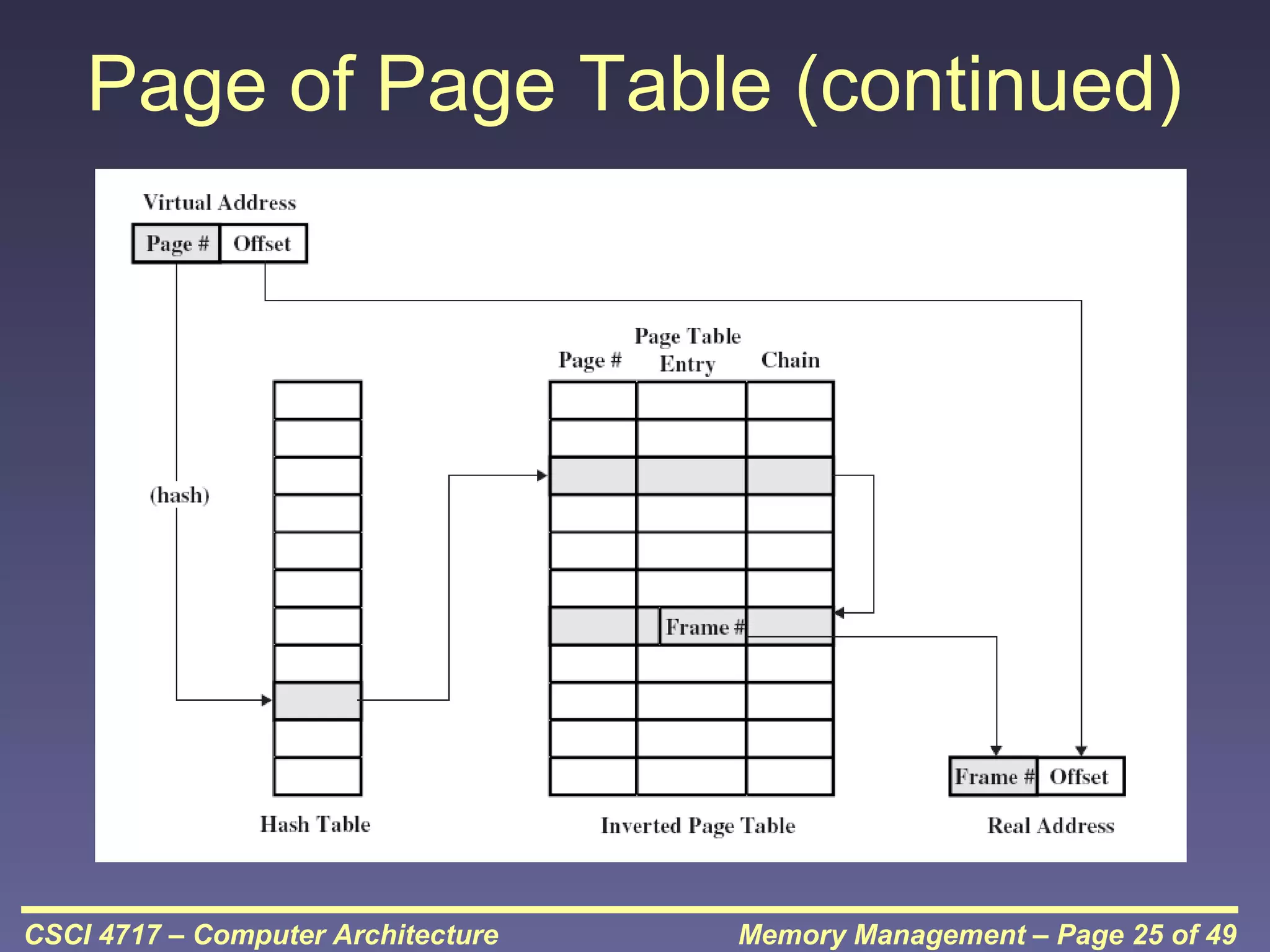

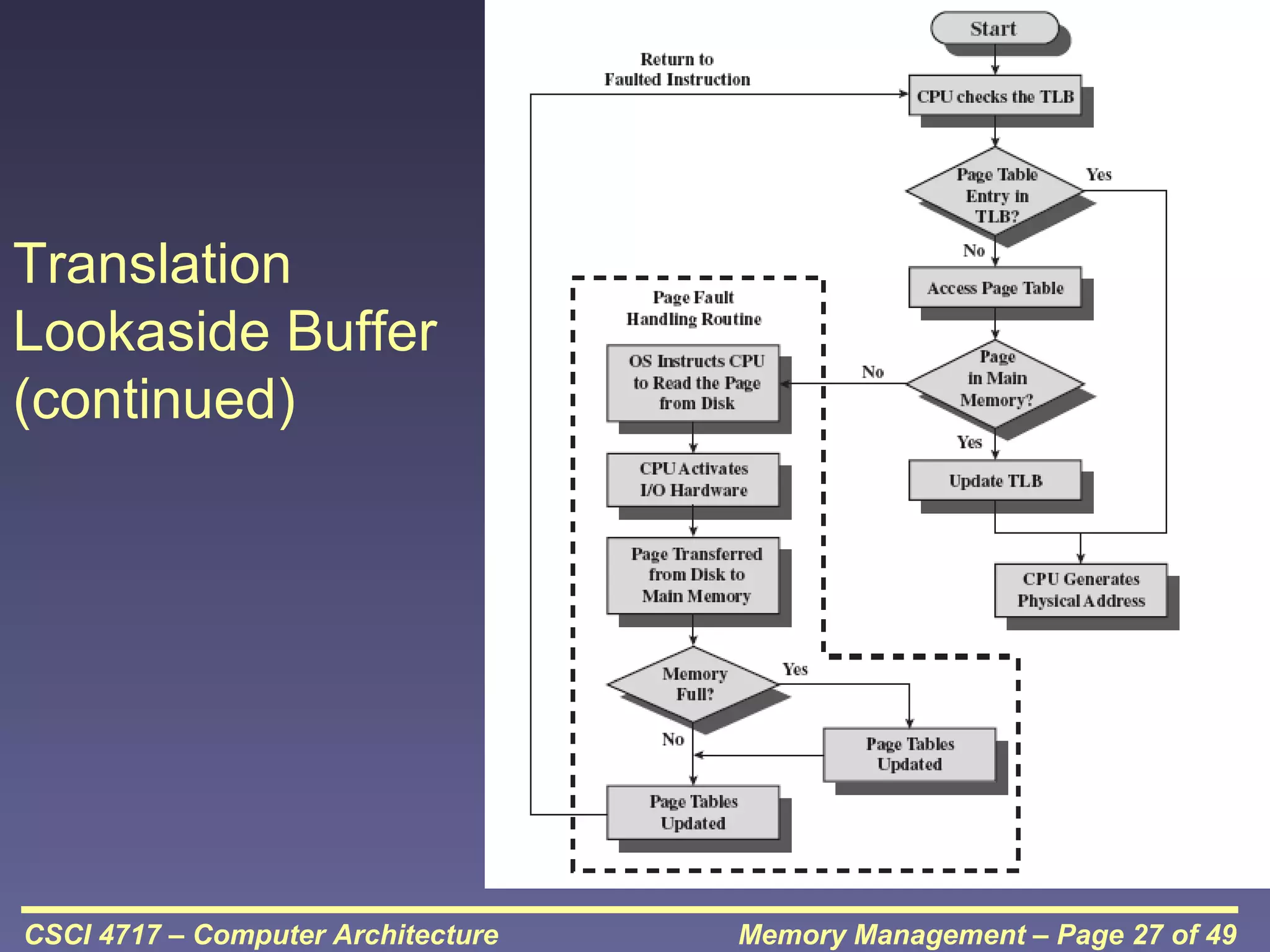

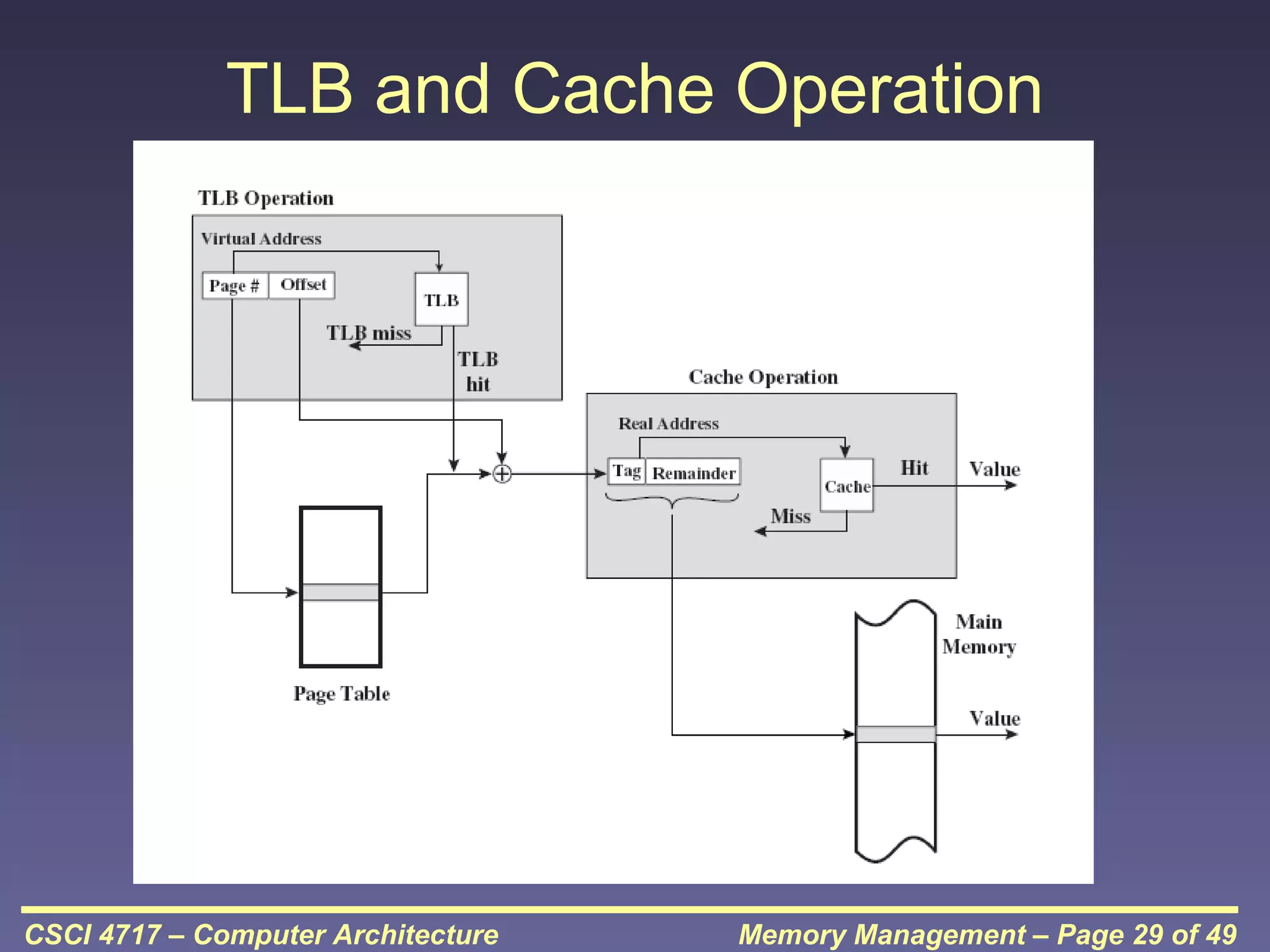

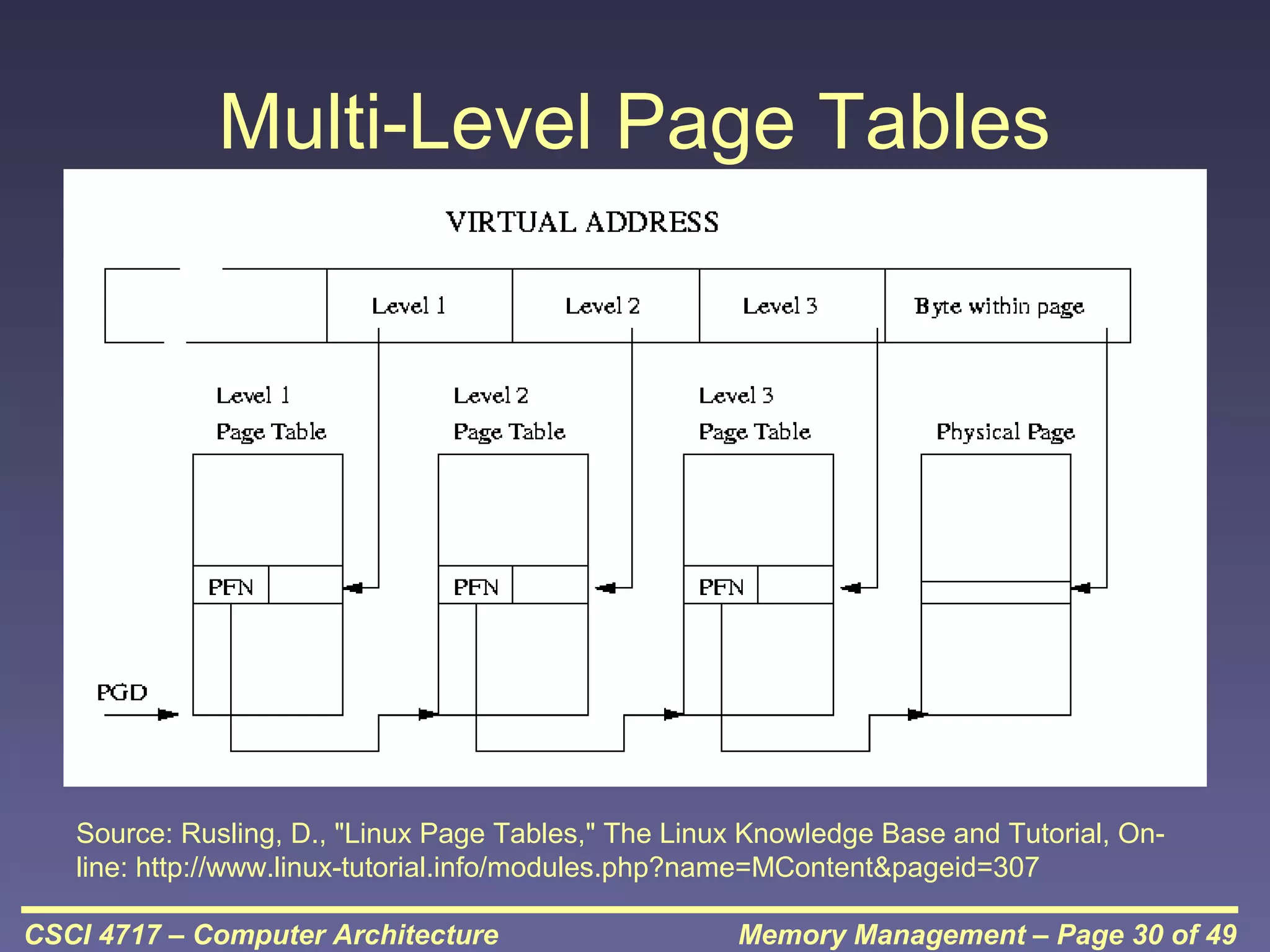

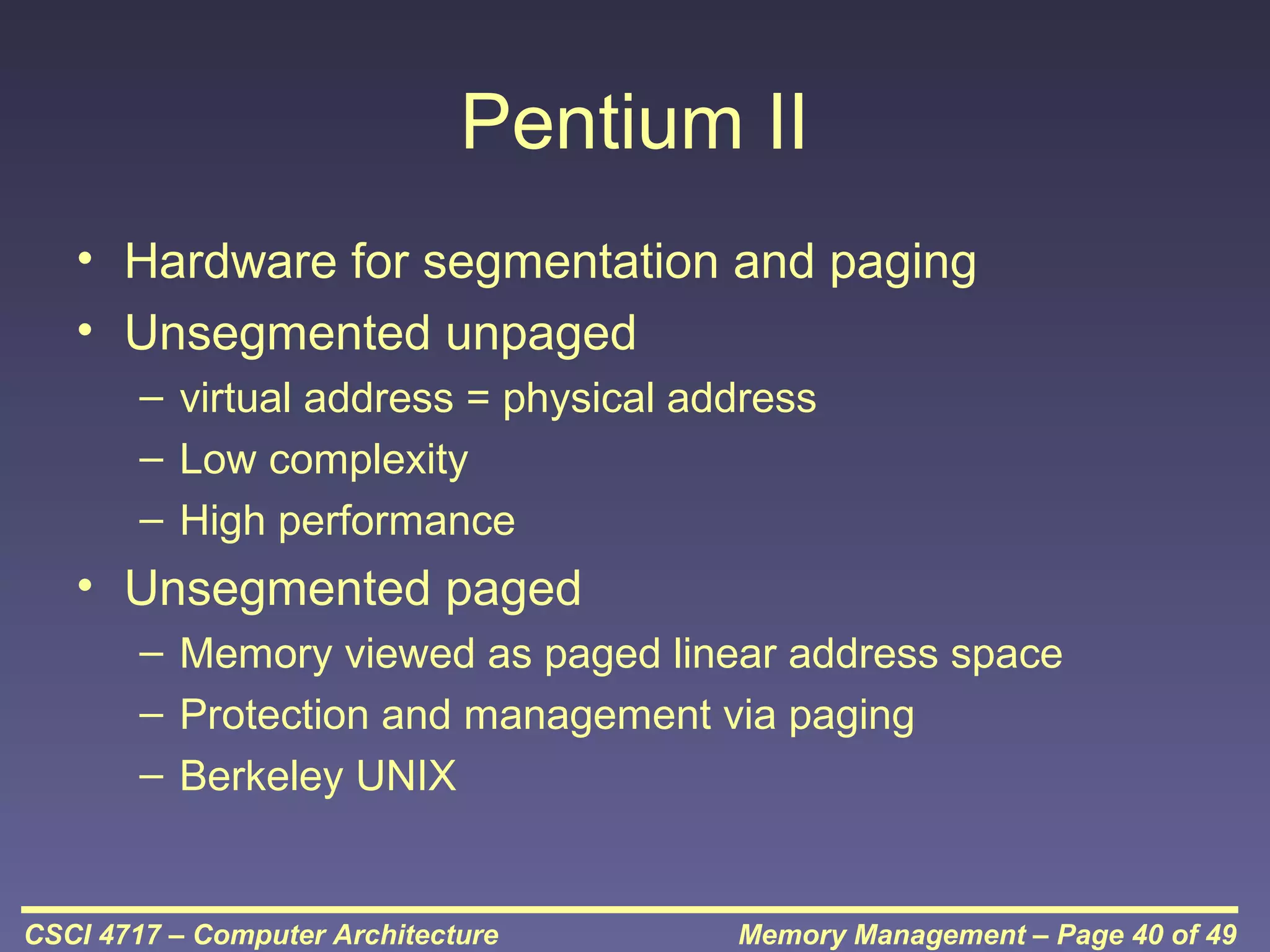

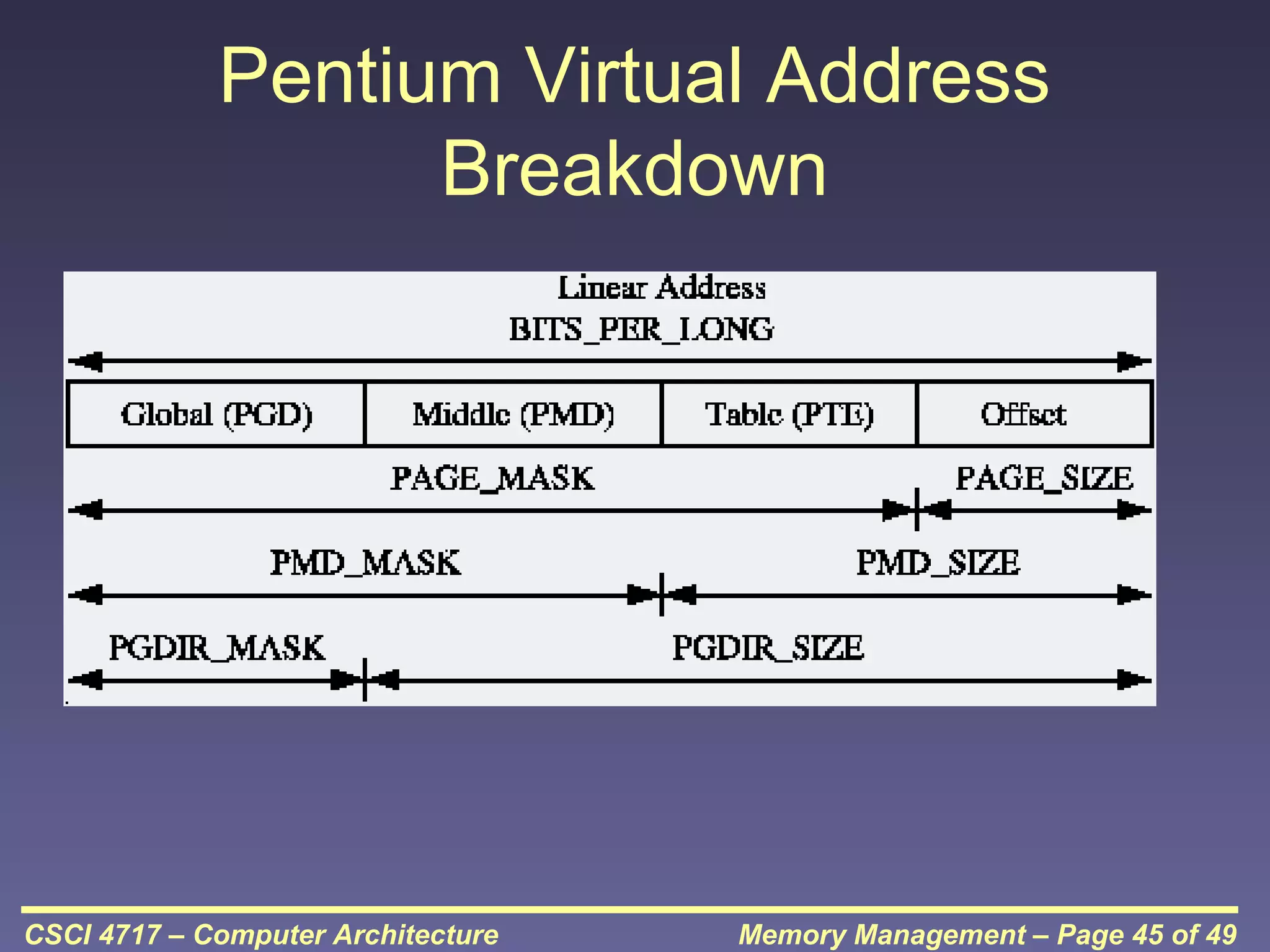

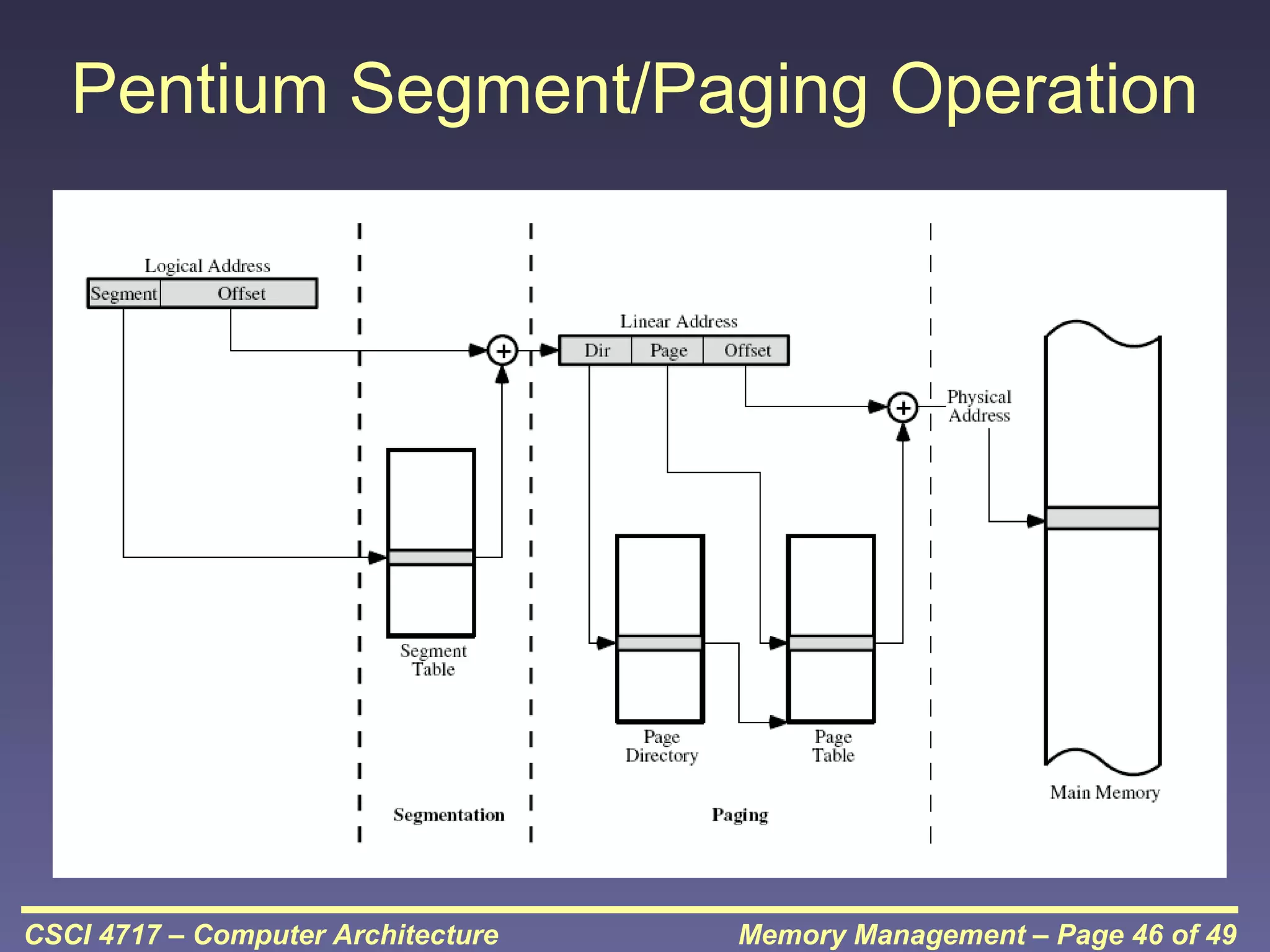

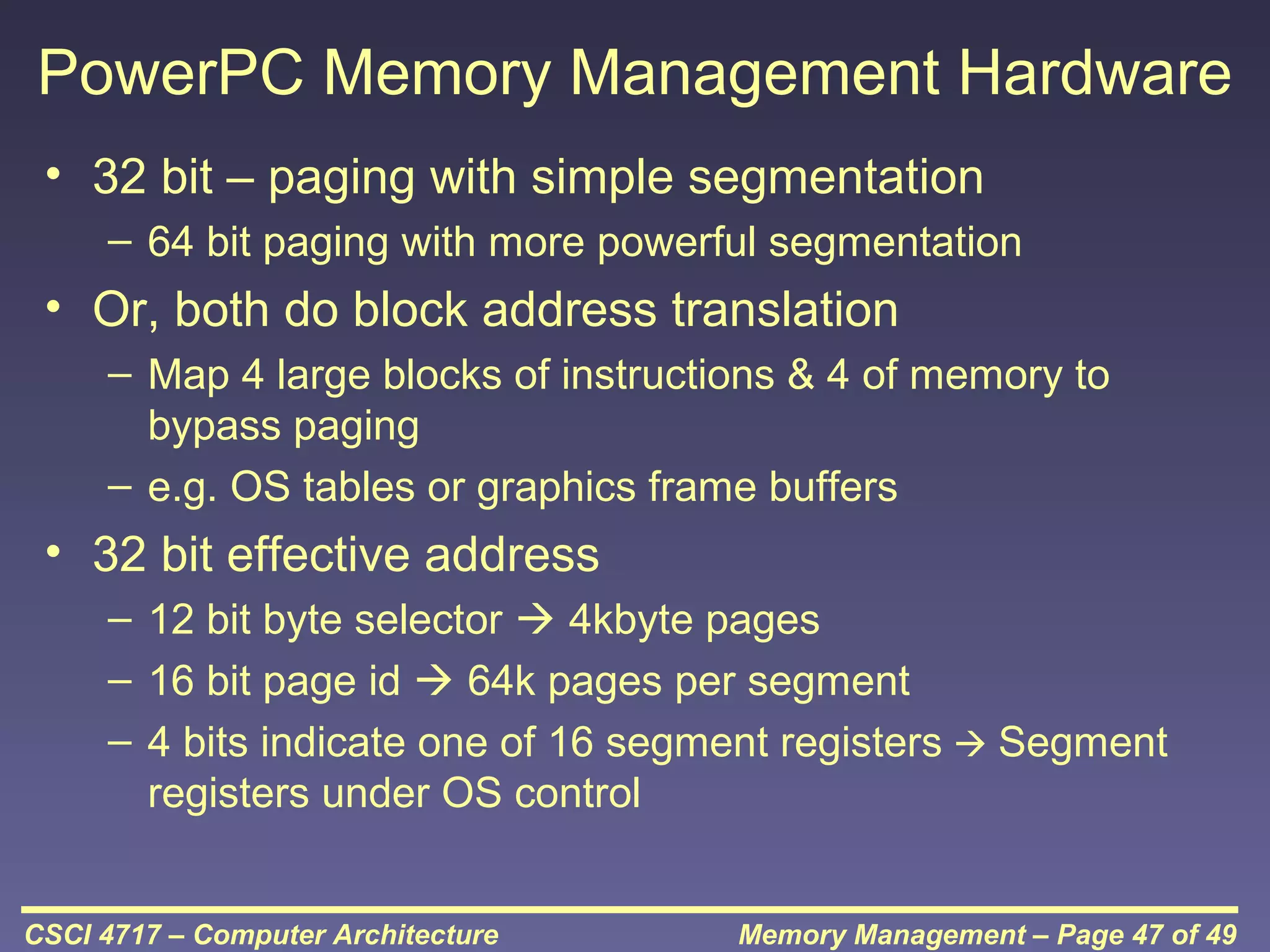

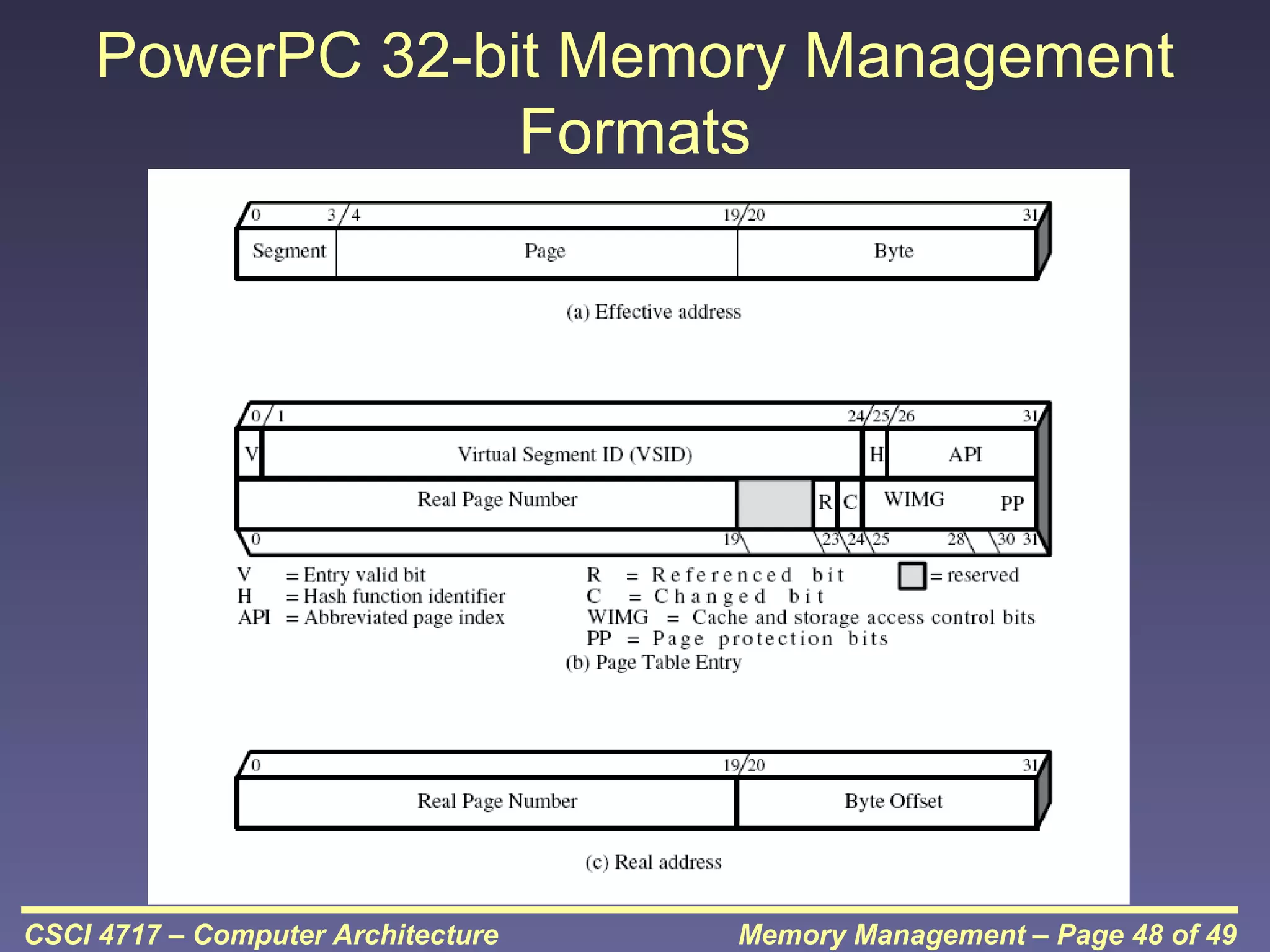

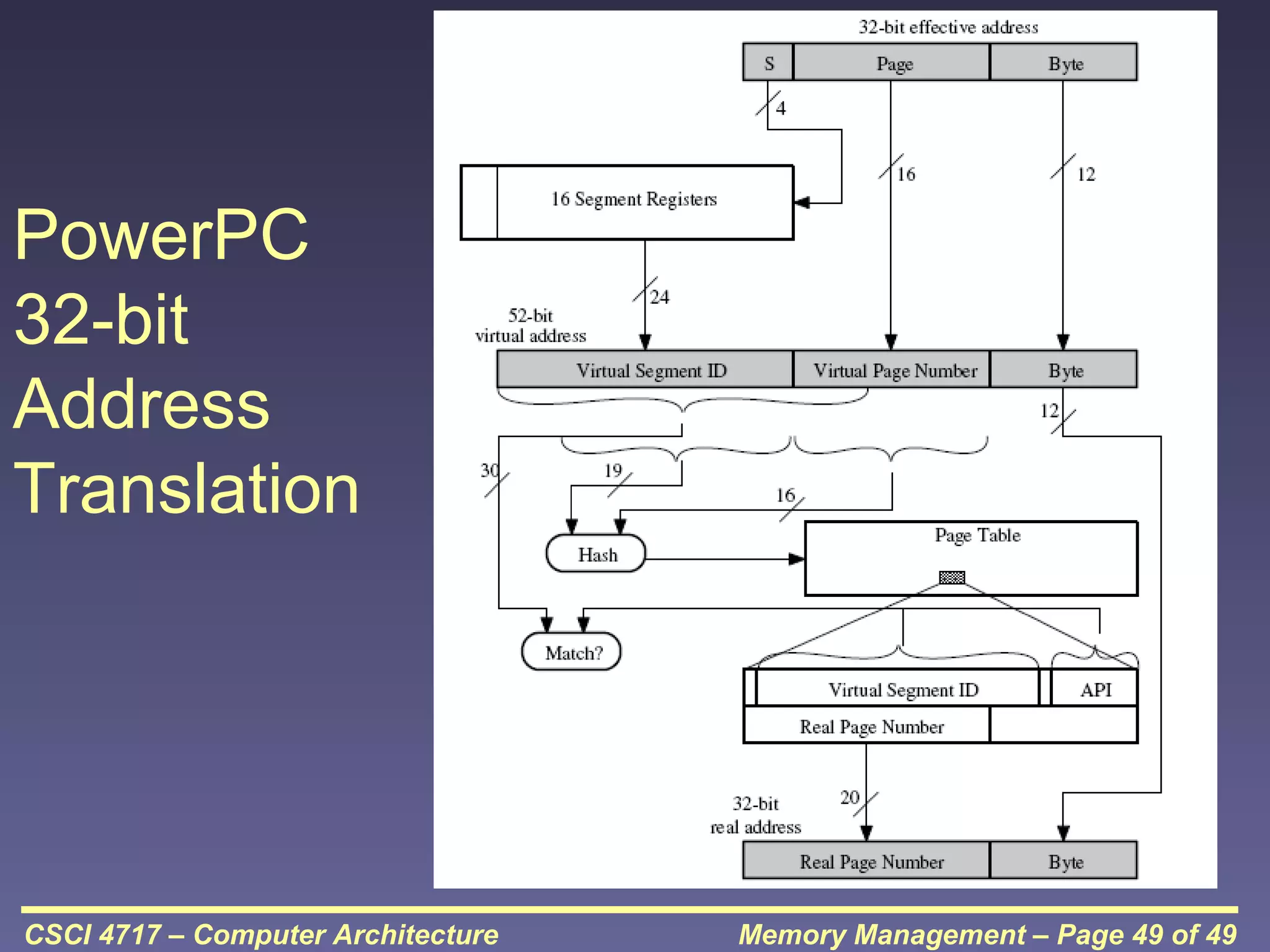

3) Paging maps processes and memory into uniform-sized pages and page frames, using a page table to track mappings and allowing non-contiguous allocation of pages to processes in memory.