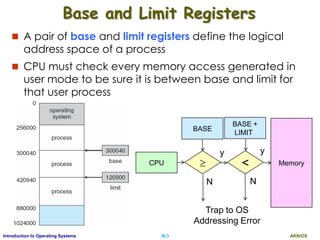

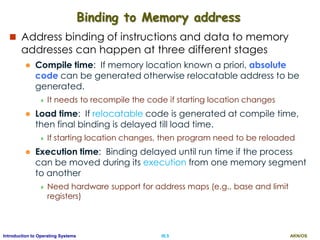

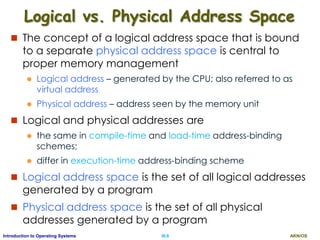

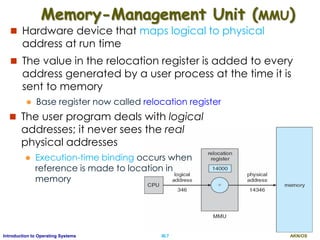

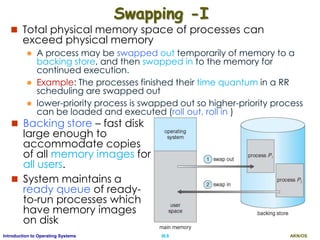

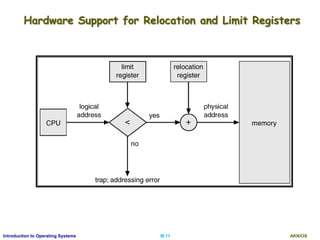

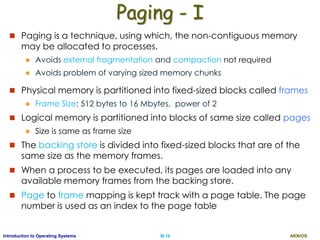

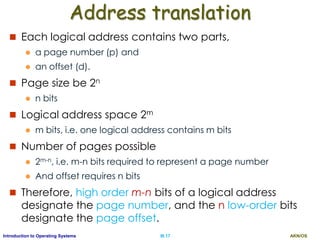

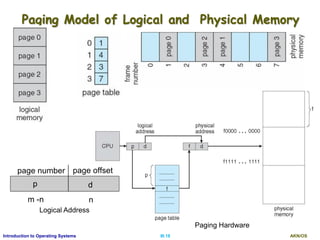

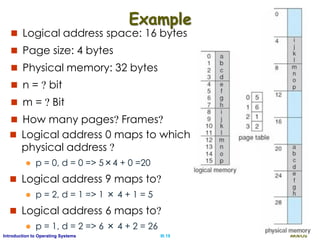

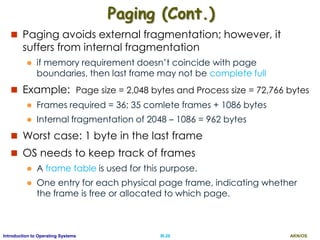

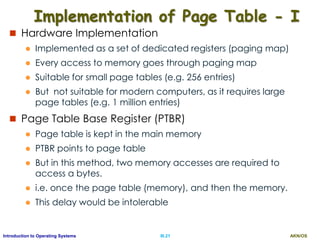

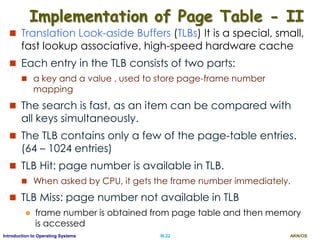

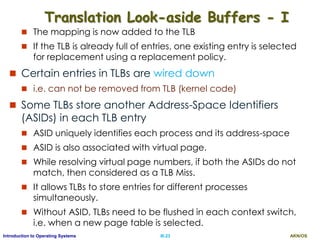

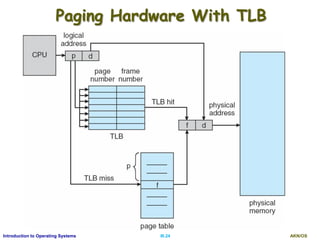

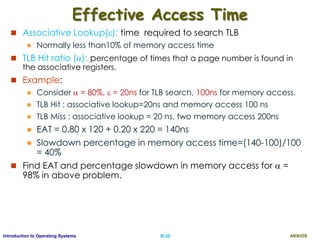

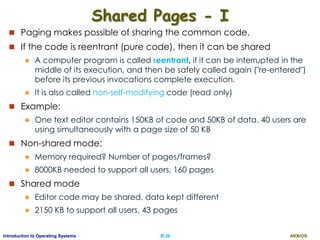

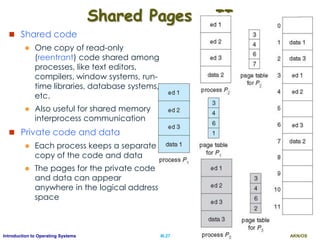

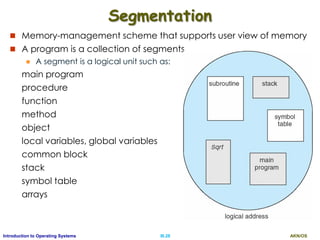

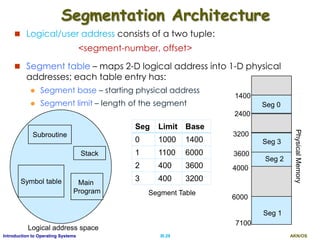

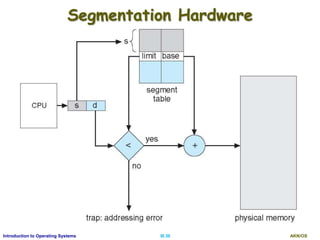

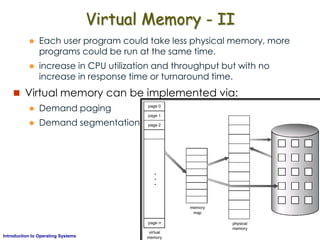

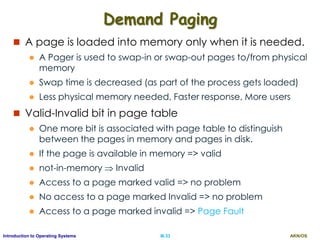

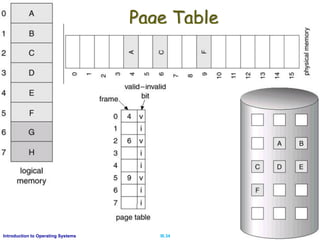

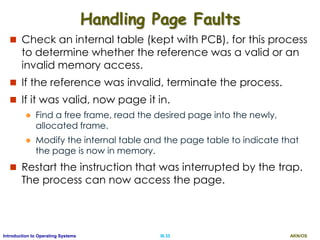

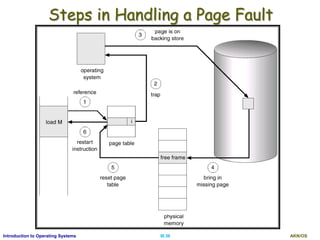

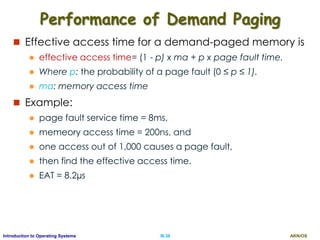

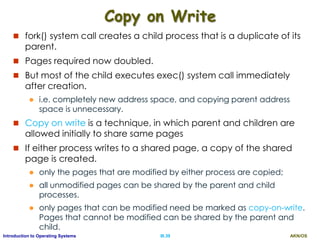

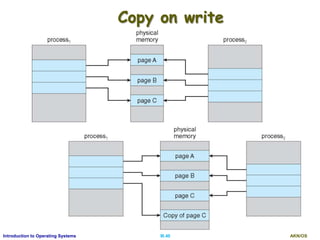

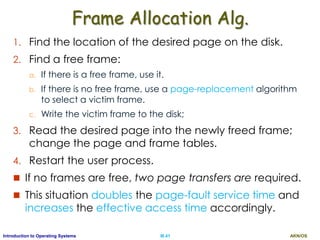

The document discusses memory management techniques in operating systems. It describes how programs must be loaded into memory to execute and memory addresses are represented at different stages. It introduces the concepts of logical and physical address spaces and how they are mapped using a memory management unit. It also summarizes common memory management techniques like paging, segmentation, and swapping that allow processes to be allocated non-contiguous regions of physical memory from a pool of memory frames and backed by disk. Paging partitions both logical and physical memory into fixed-size pages and frames, using a page table to map virtual to physical addresses.