This document provides guidance on the management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. It discusses:

1) Performing a thorough history and physical exam to assess bleeding severity, risk factors, and stability. Guaiac testing has limited utility for inpatients.

2) Initial stabilization including IV access, fluid resuscitation, PPI administration, and consideration of ICU care for unstable patients.

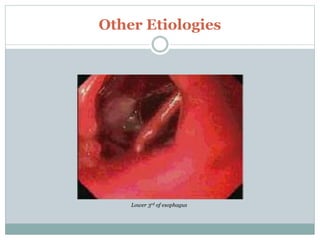

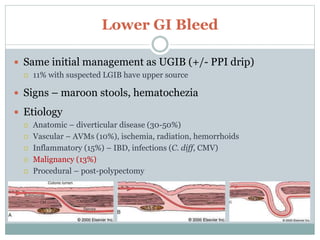

3) Etiologies of upper and lower GI bleeding and their typical clinical presentations. Endoscopic therapies are usually first-line but angiography or surgery may be needed for active or refractory bleeding.