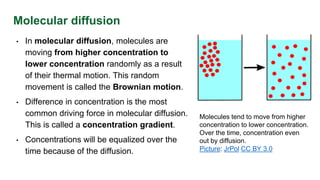

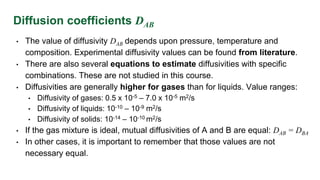

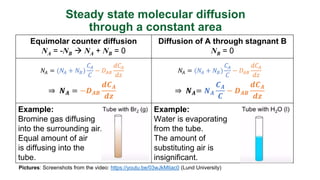

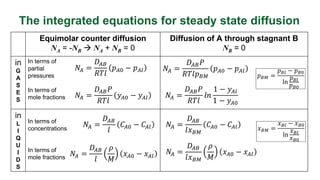

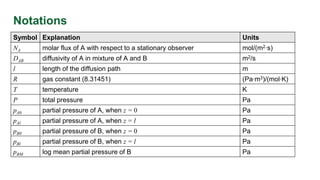

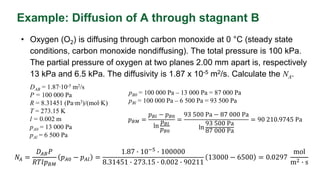

This document provides an overview of molecular diffusion, detailing its mechanisms driven primarily by concentration gradients, and introduces Fick's laws to describe the molar flux in binary mixtures. It covers various types of diffusion, diffusivity coefficients, and examples of gas diffusion calculations under steady-state conditions. The project is funded by the EU's Horizon 2020 programme and references several academic sources for further reading.