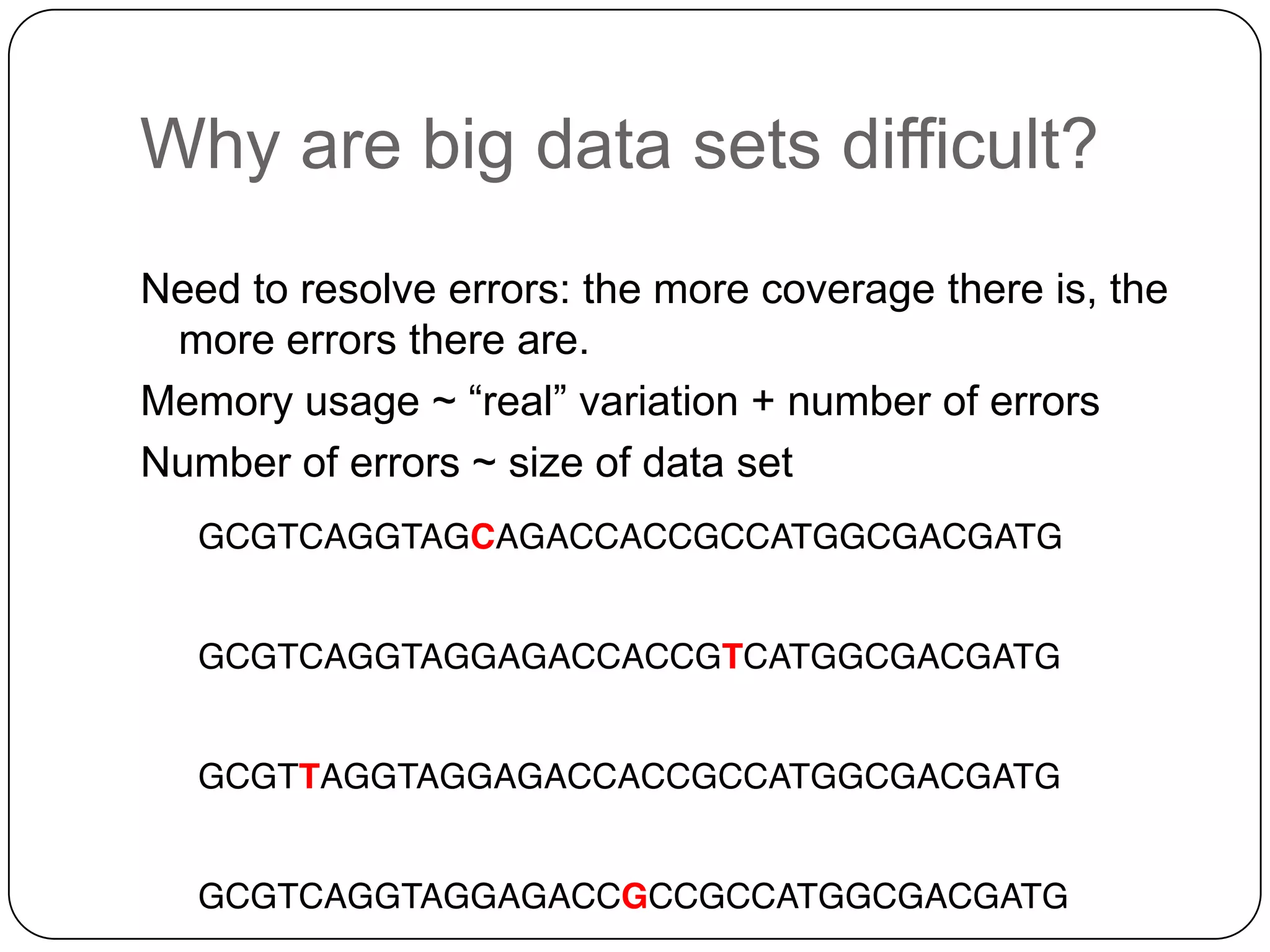

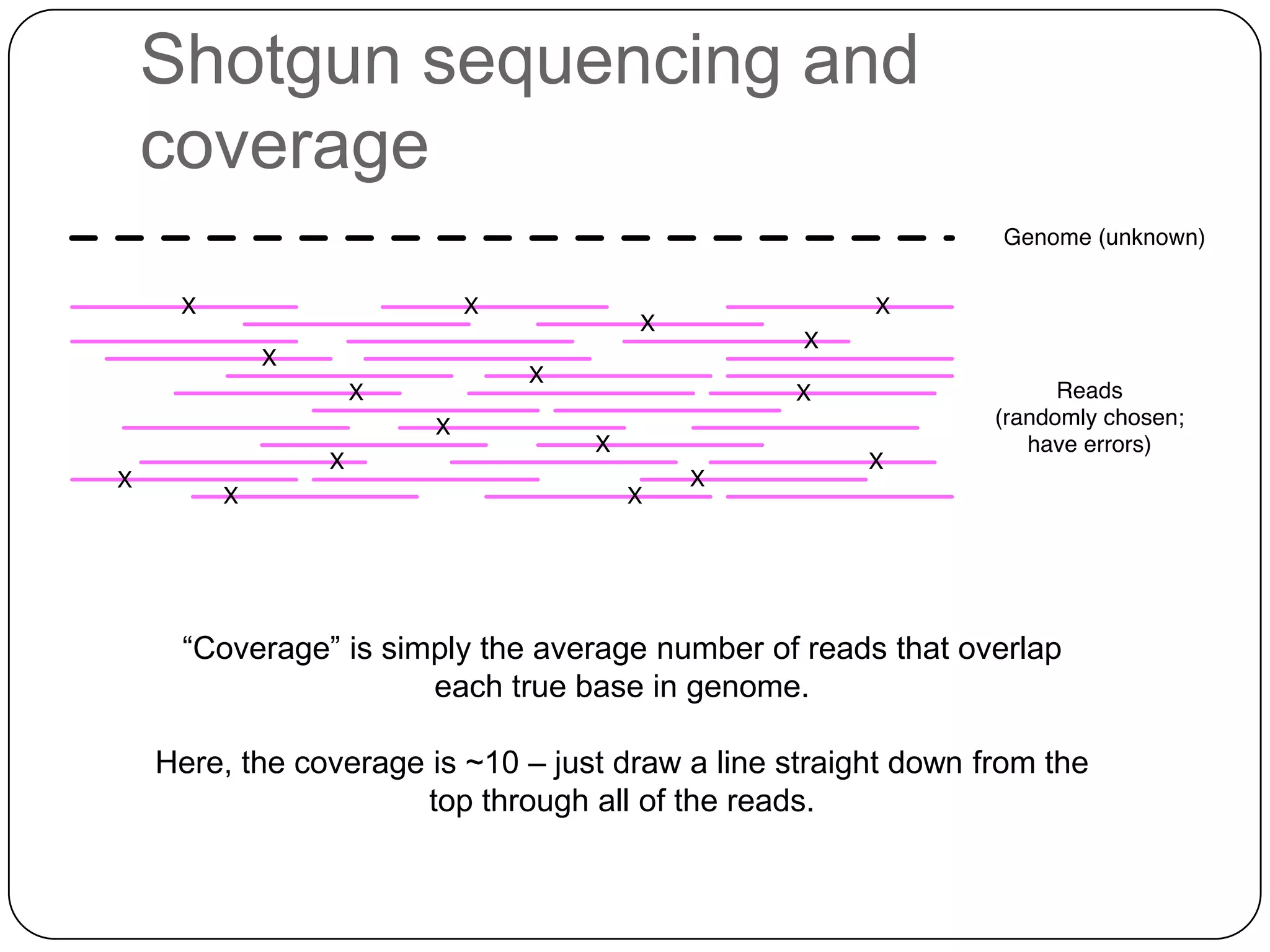

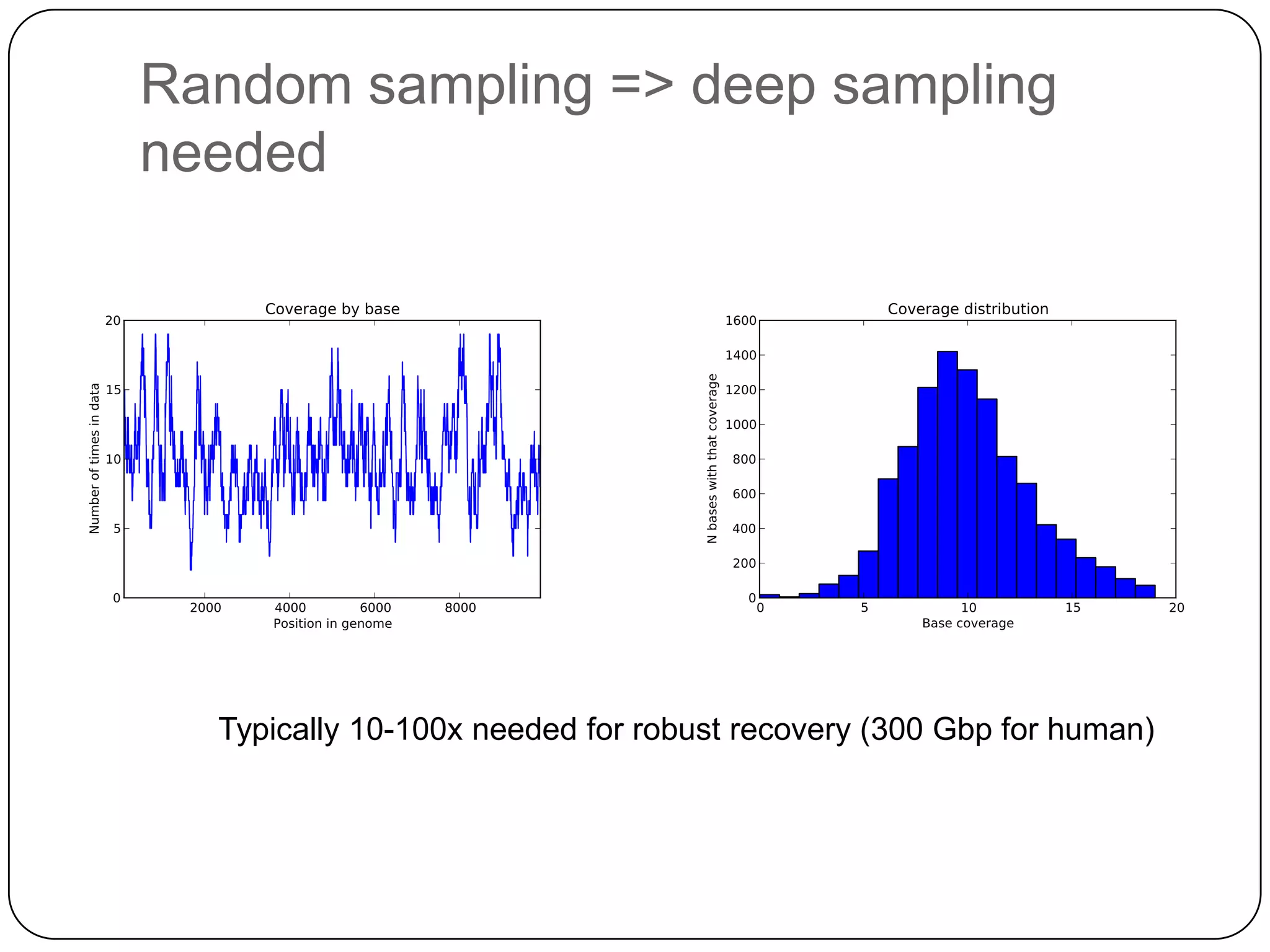

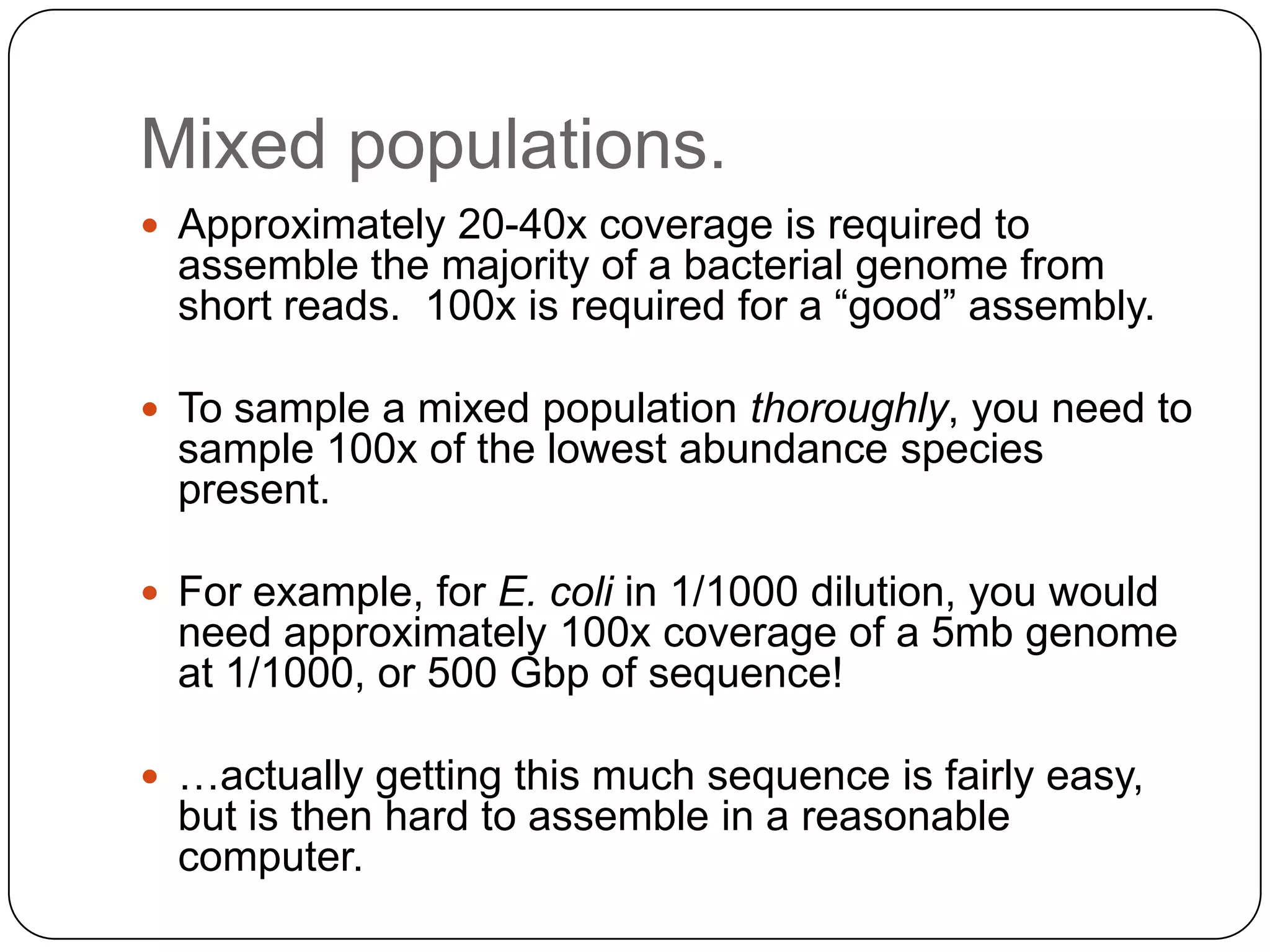

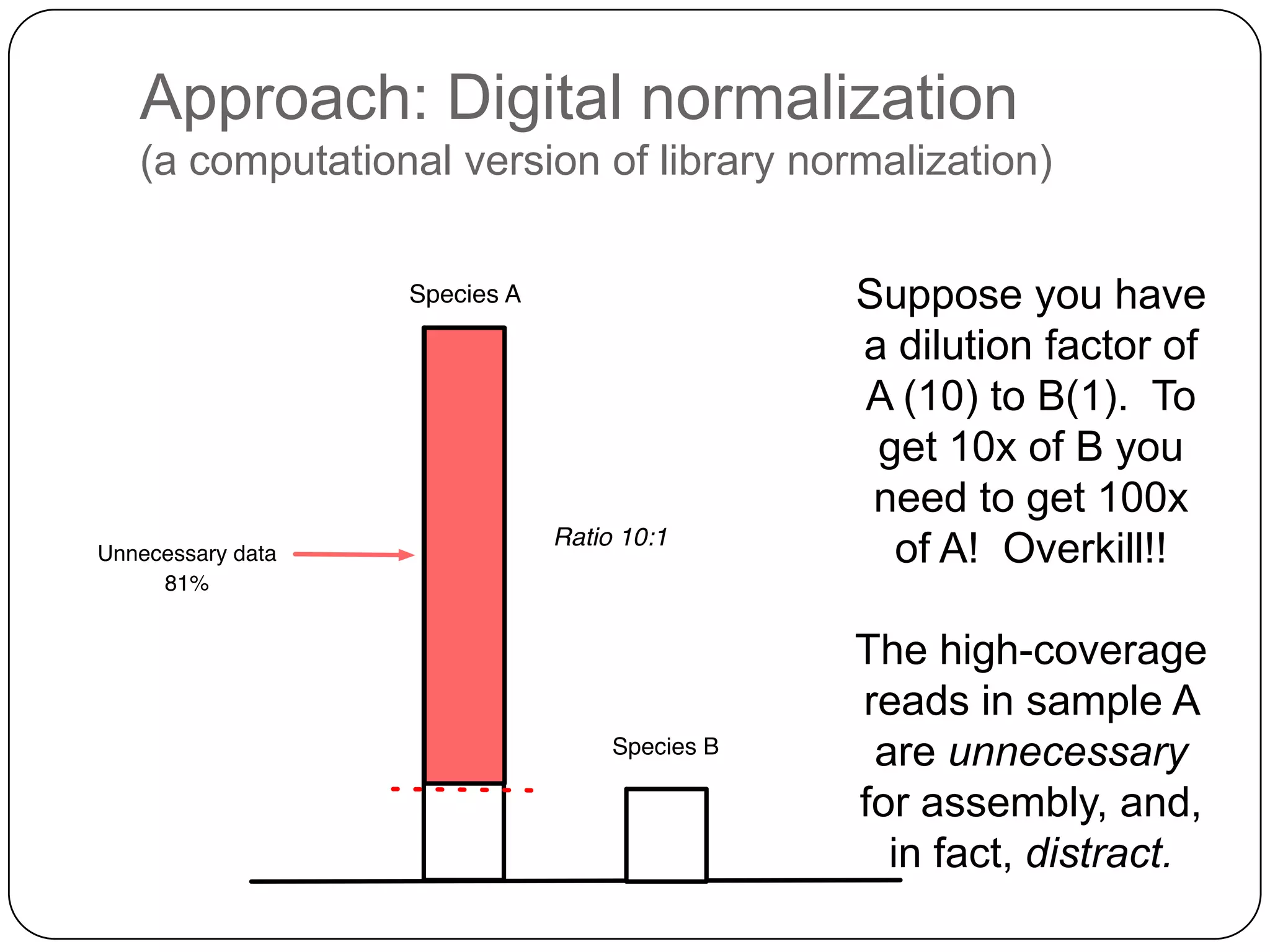

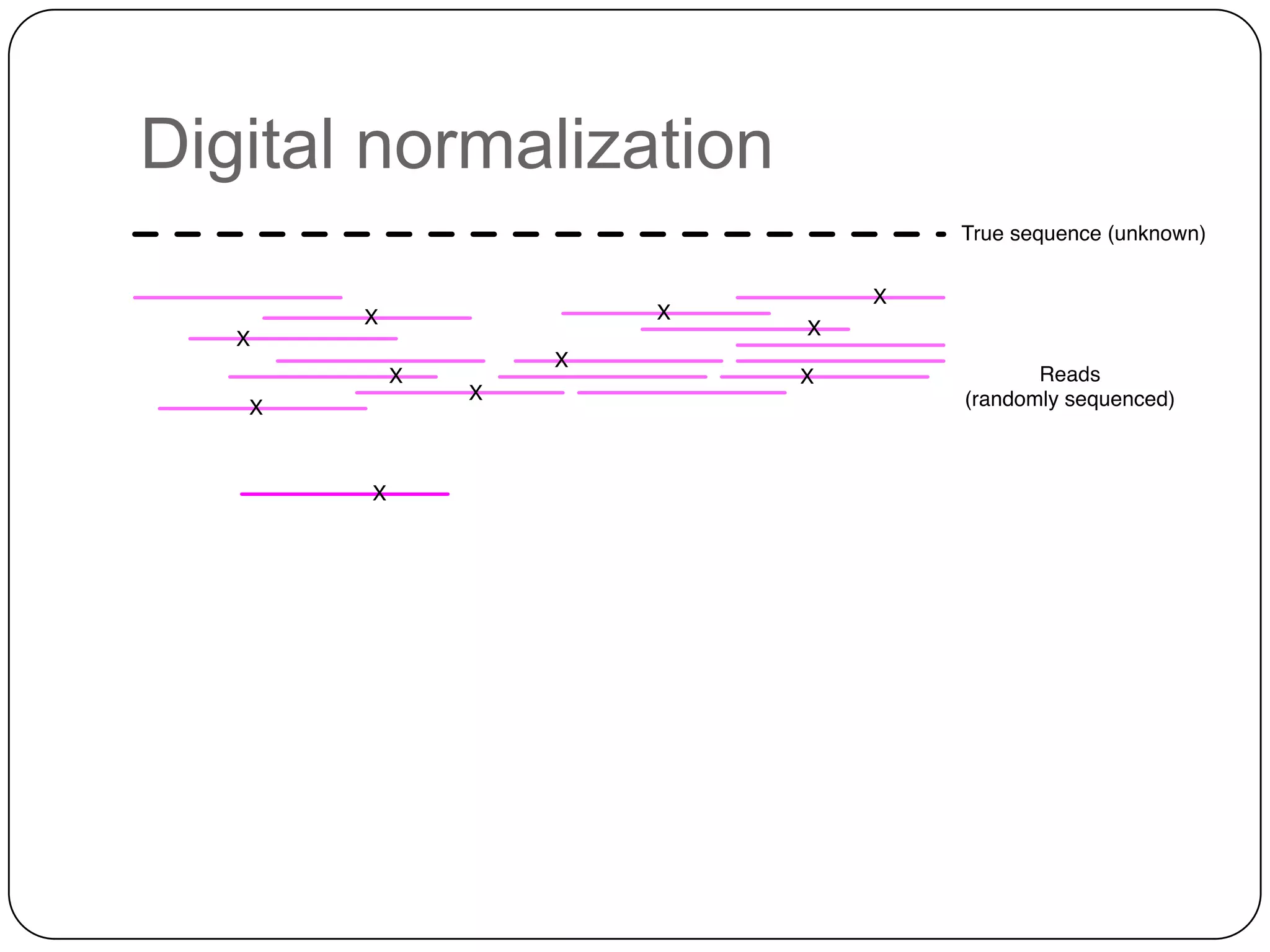

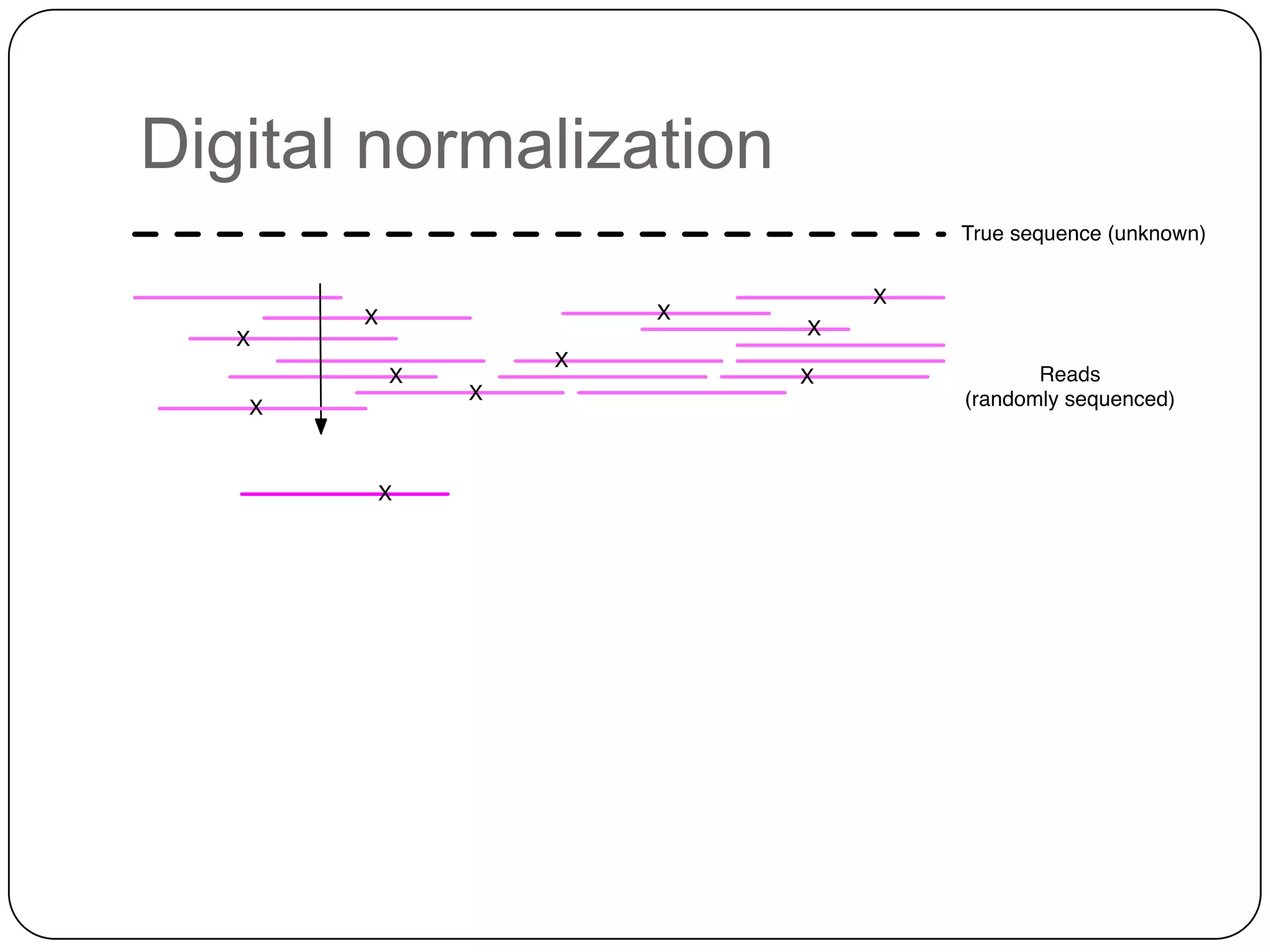

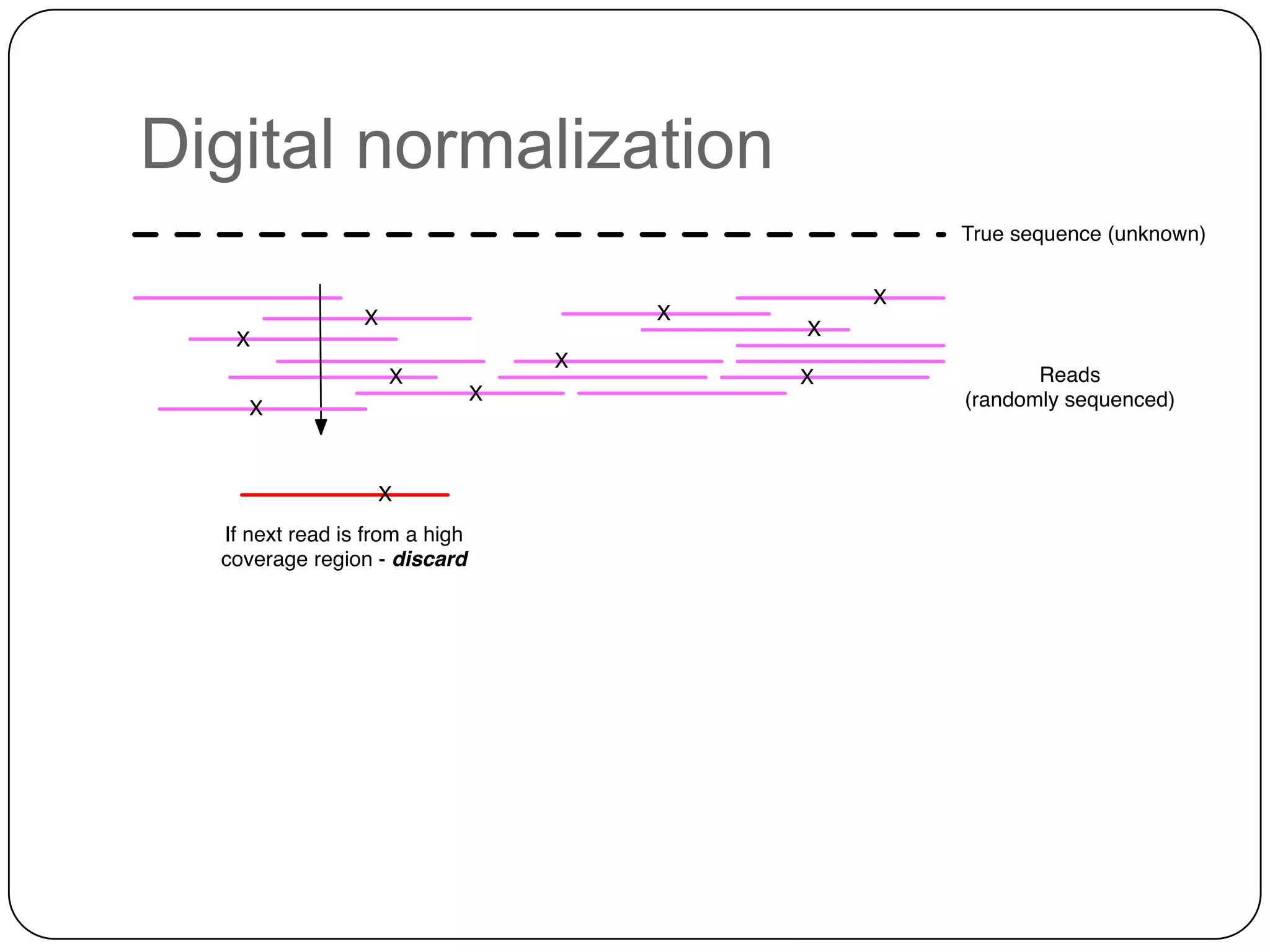

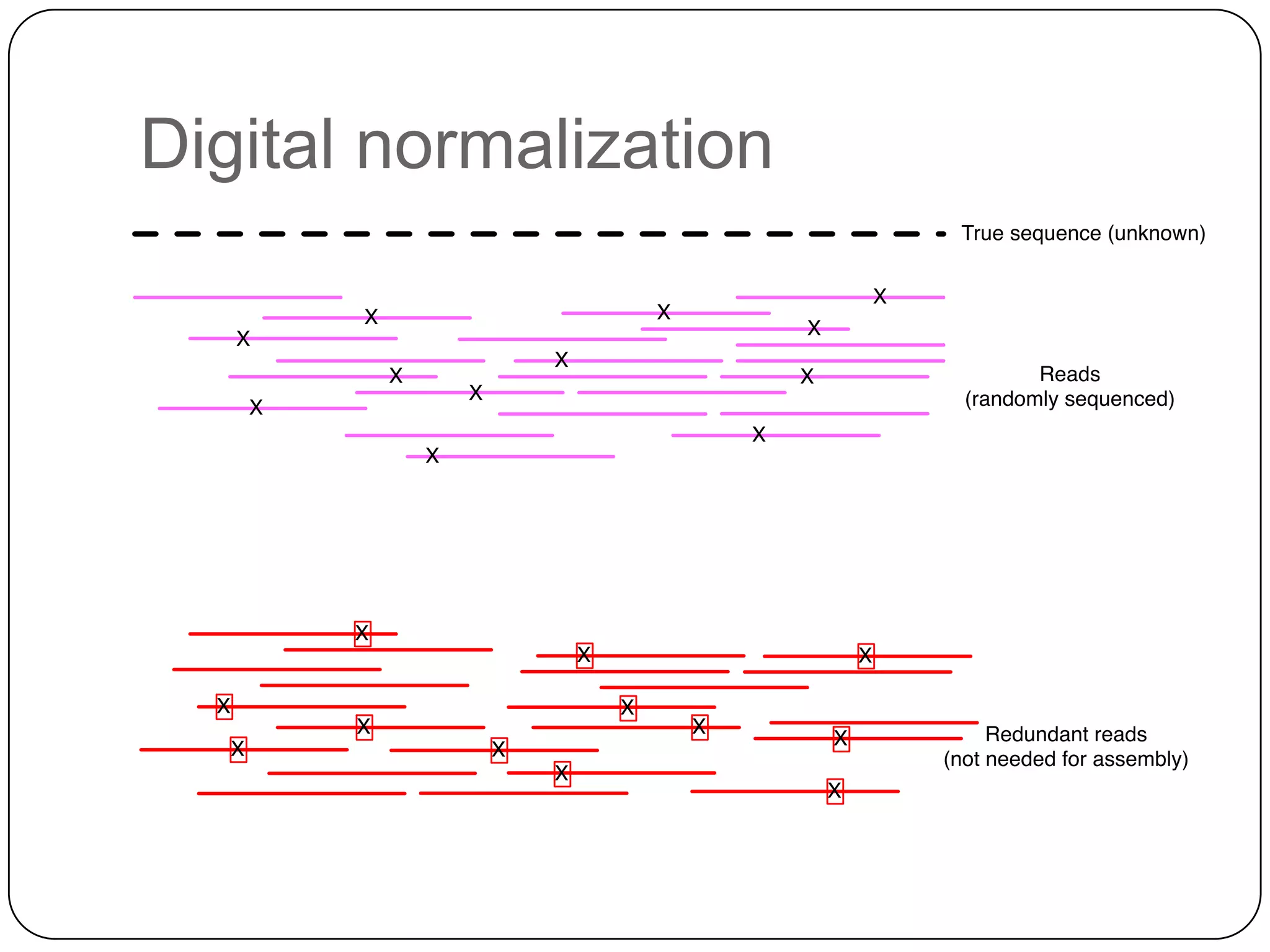

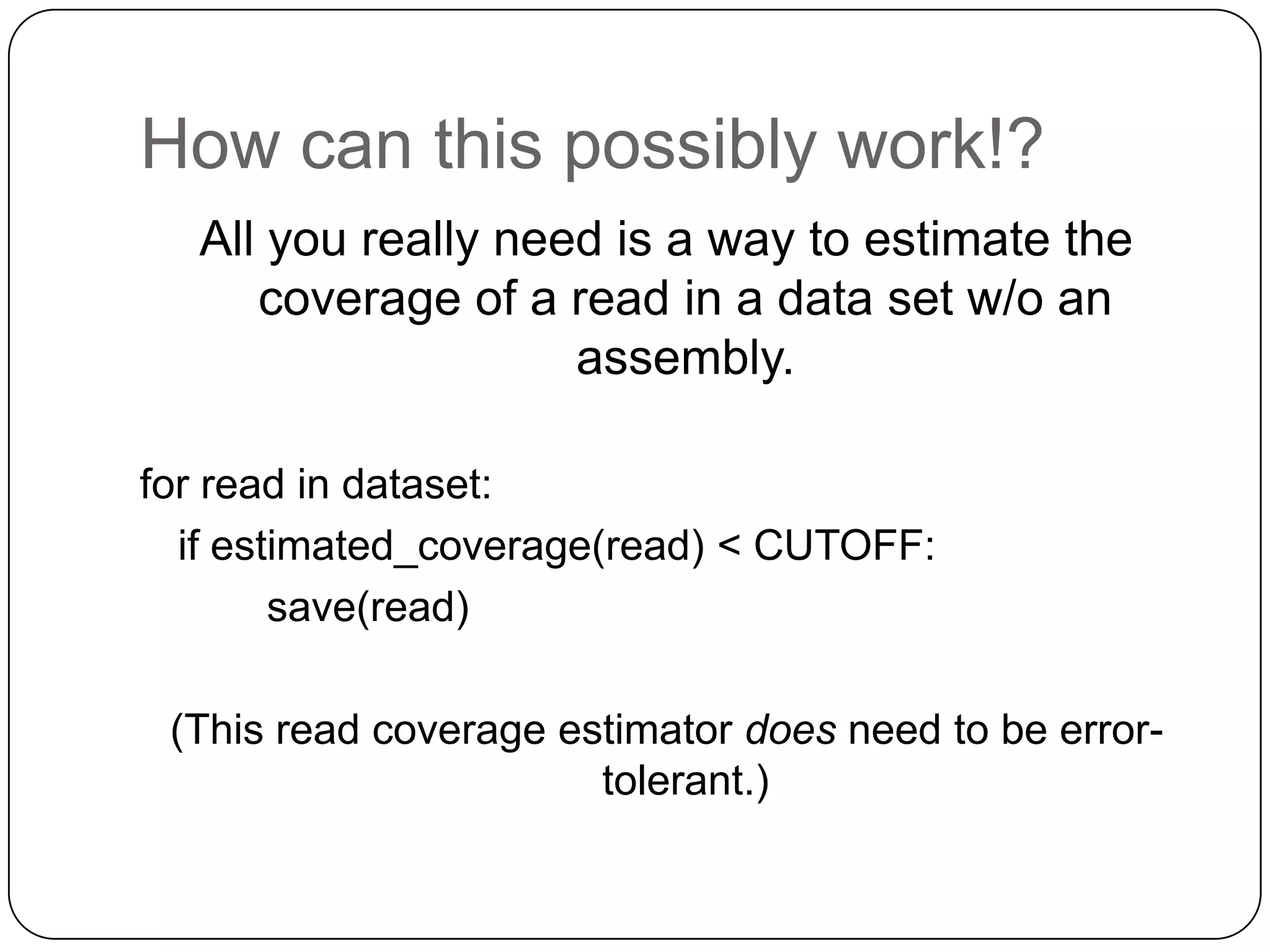

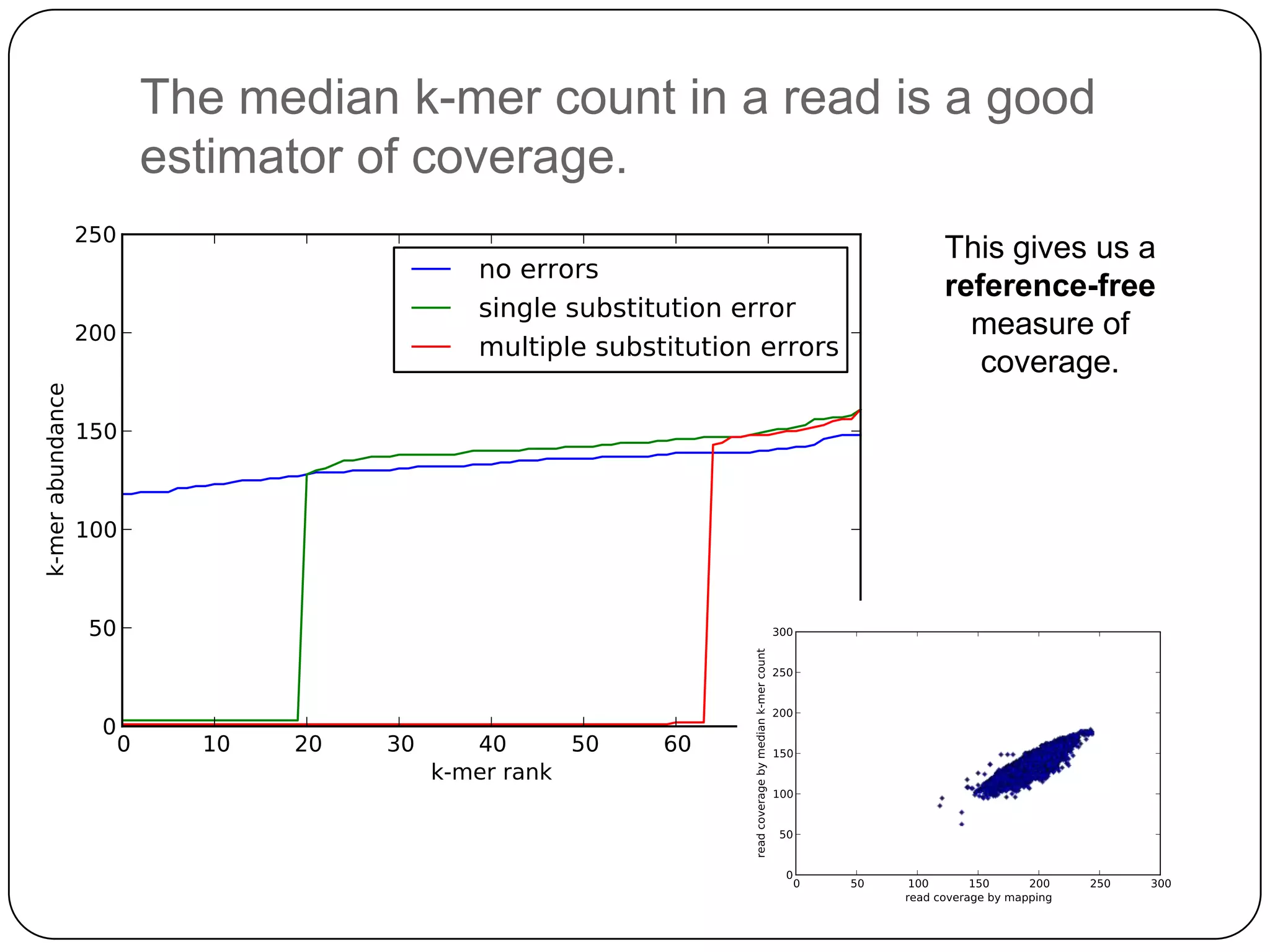

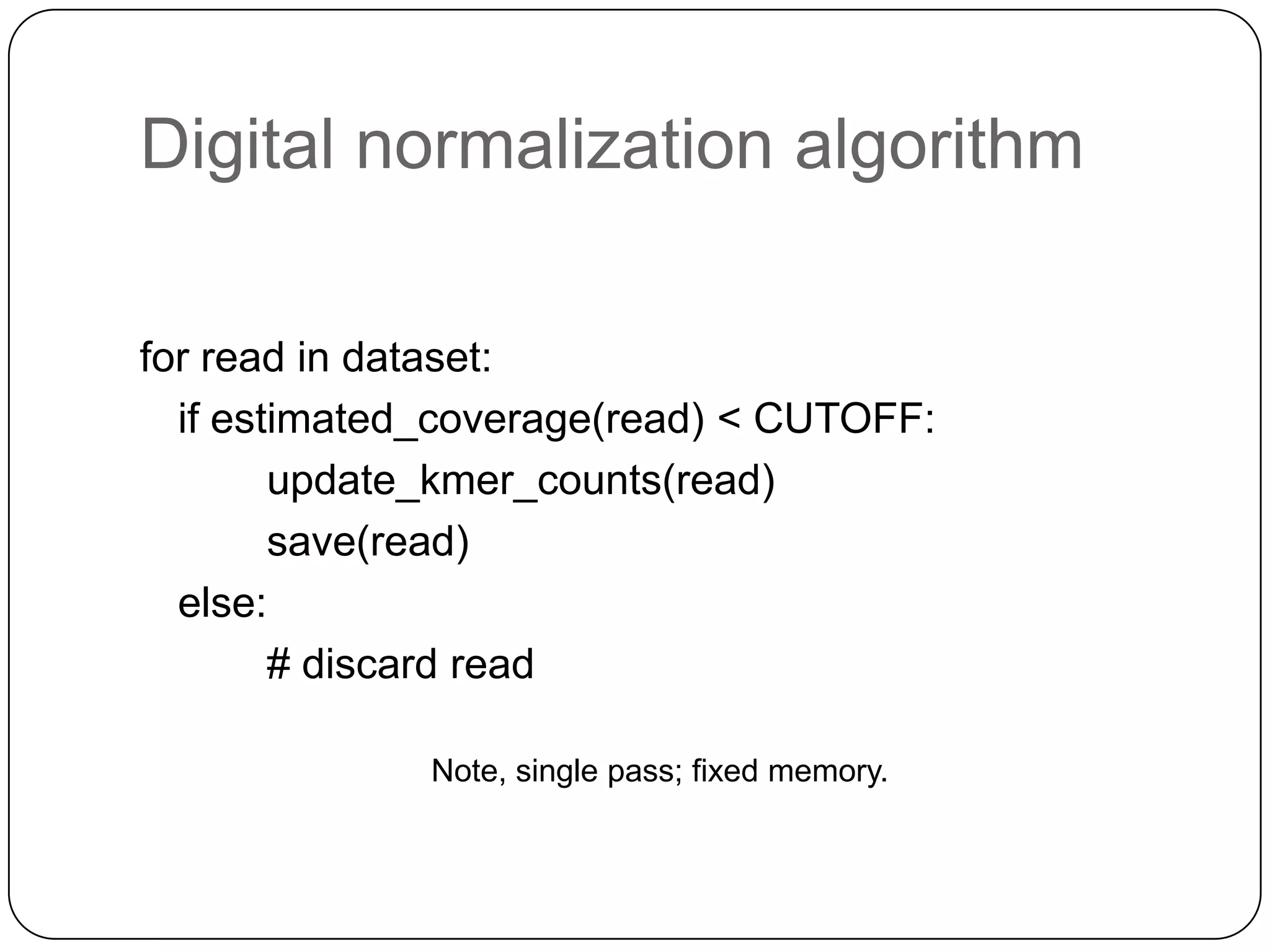

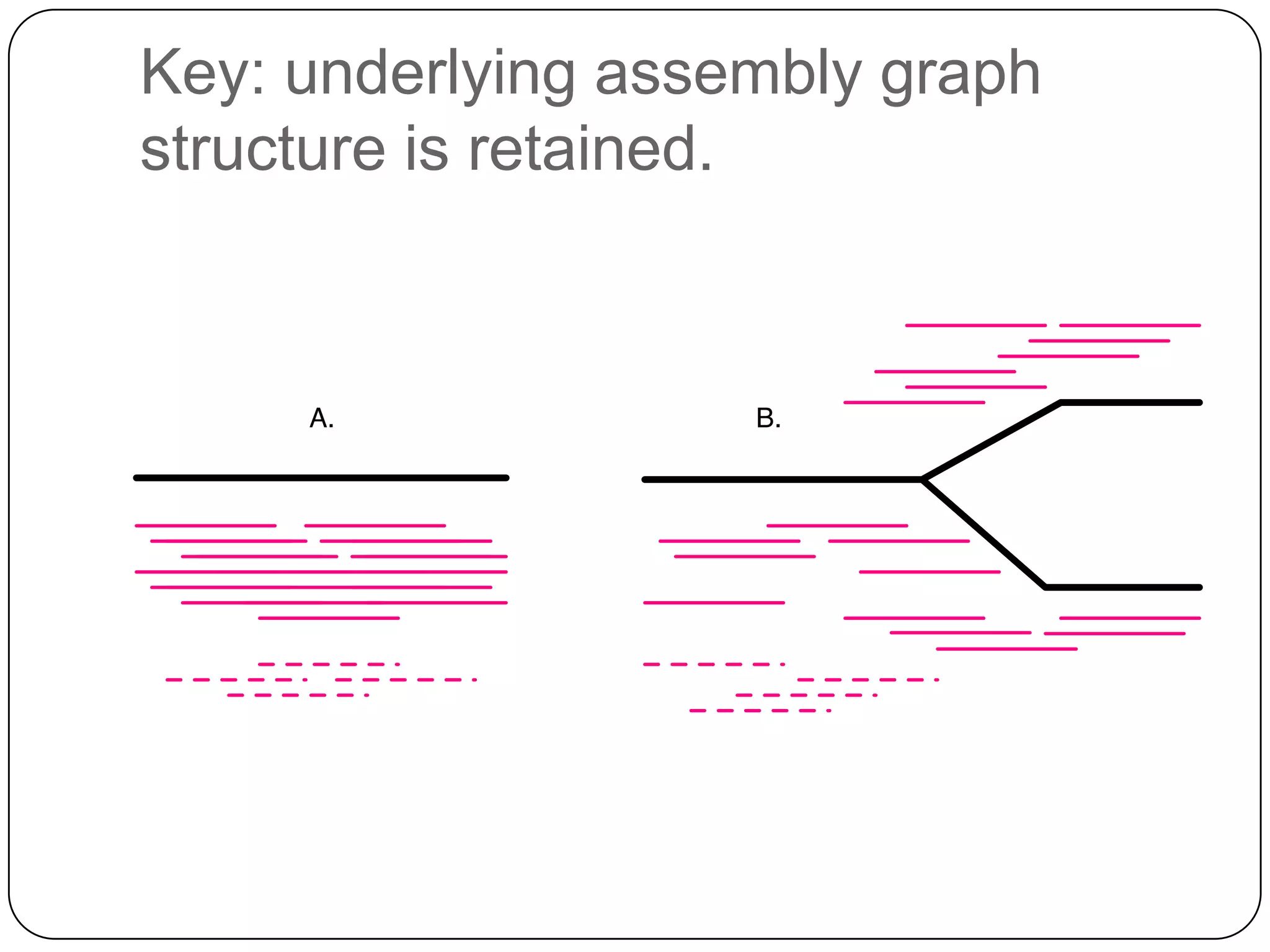

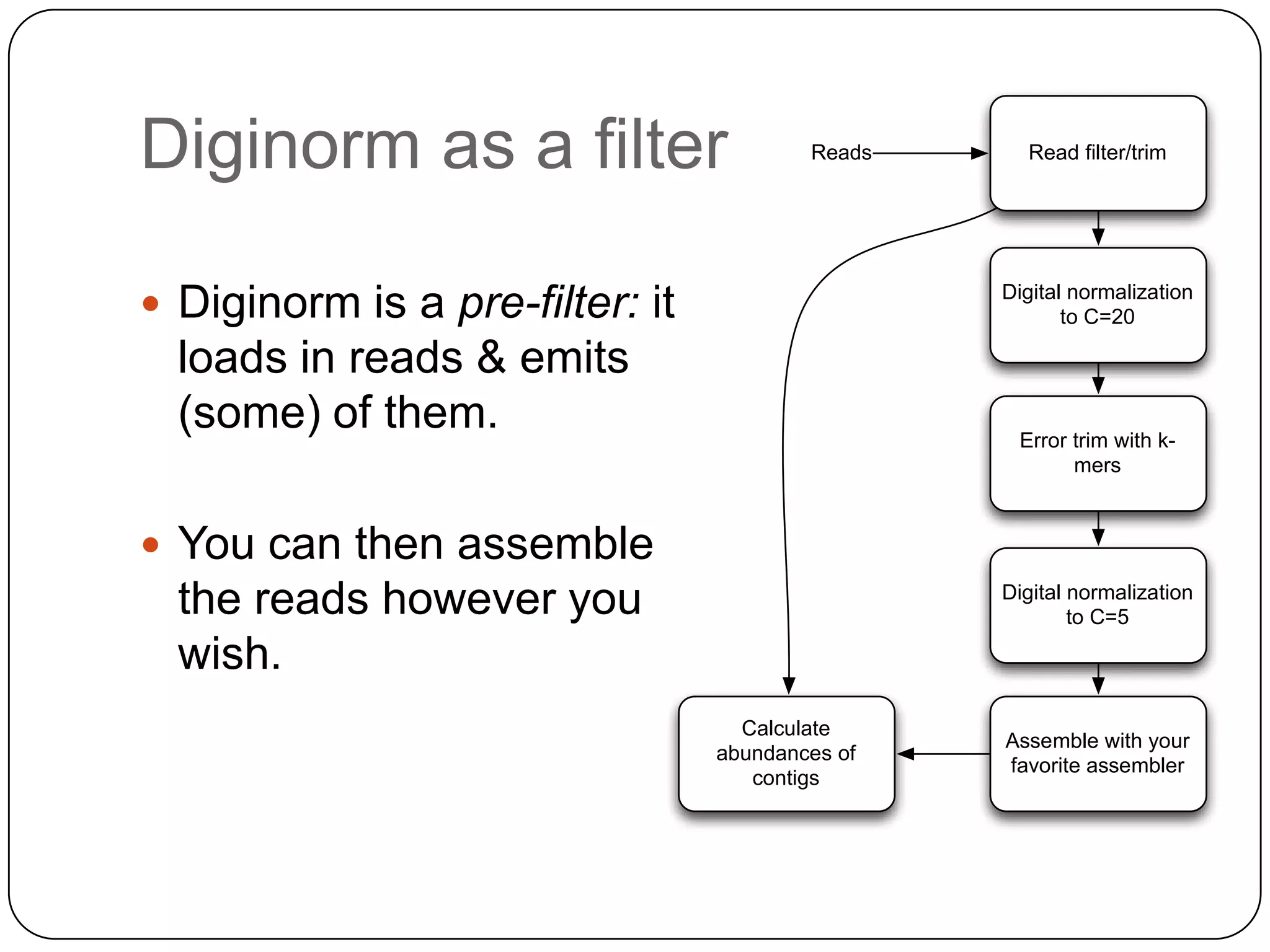

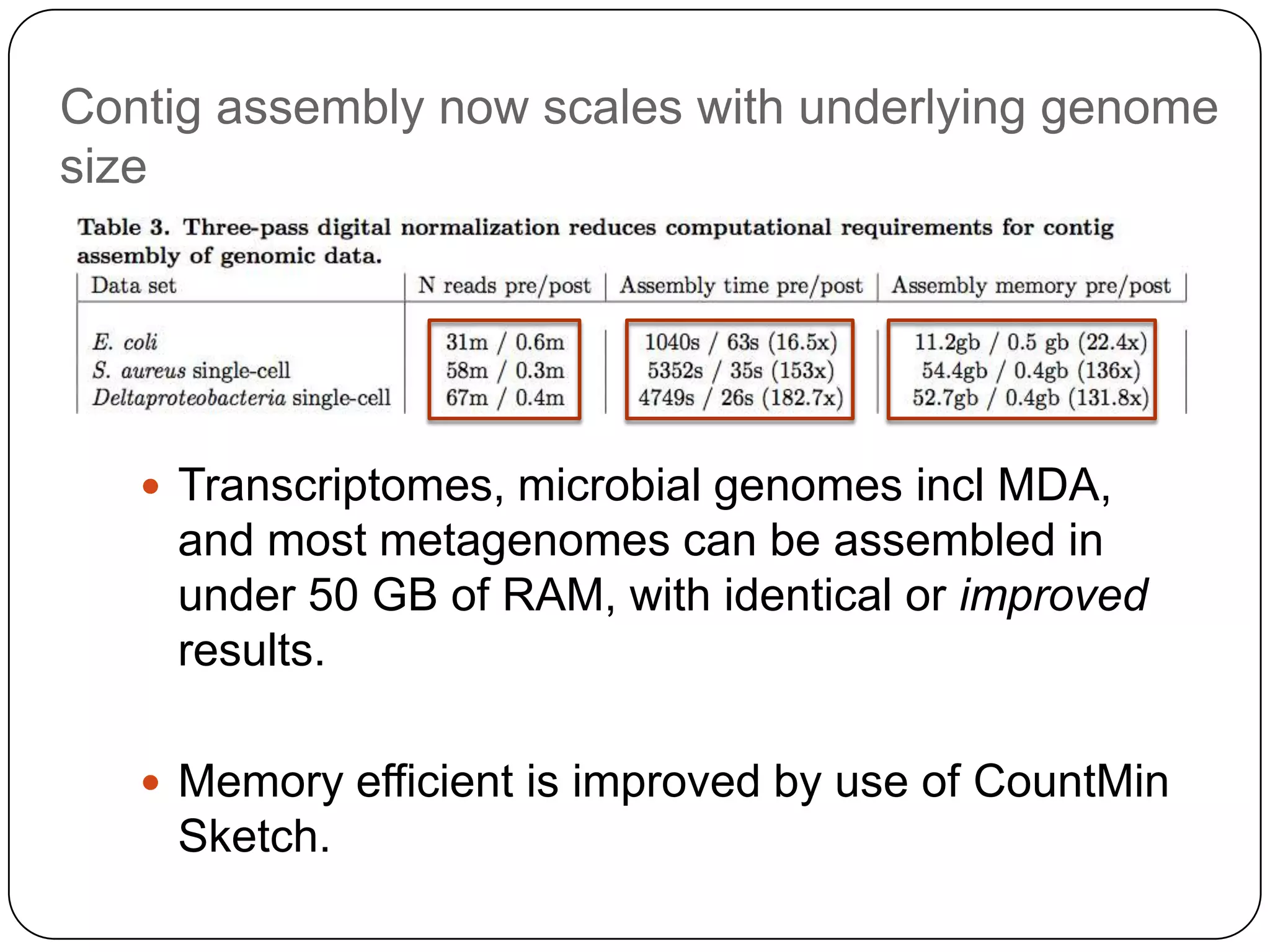

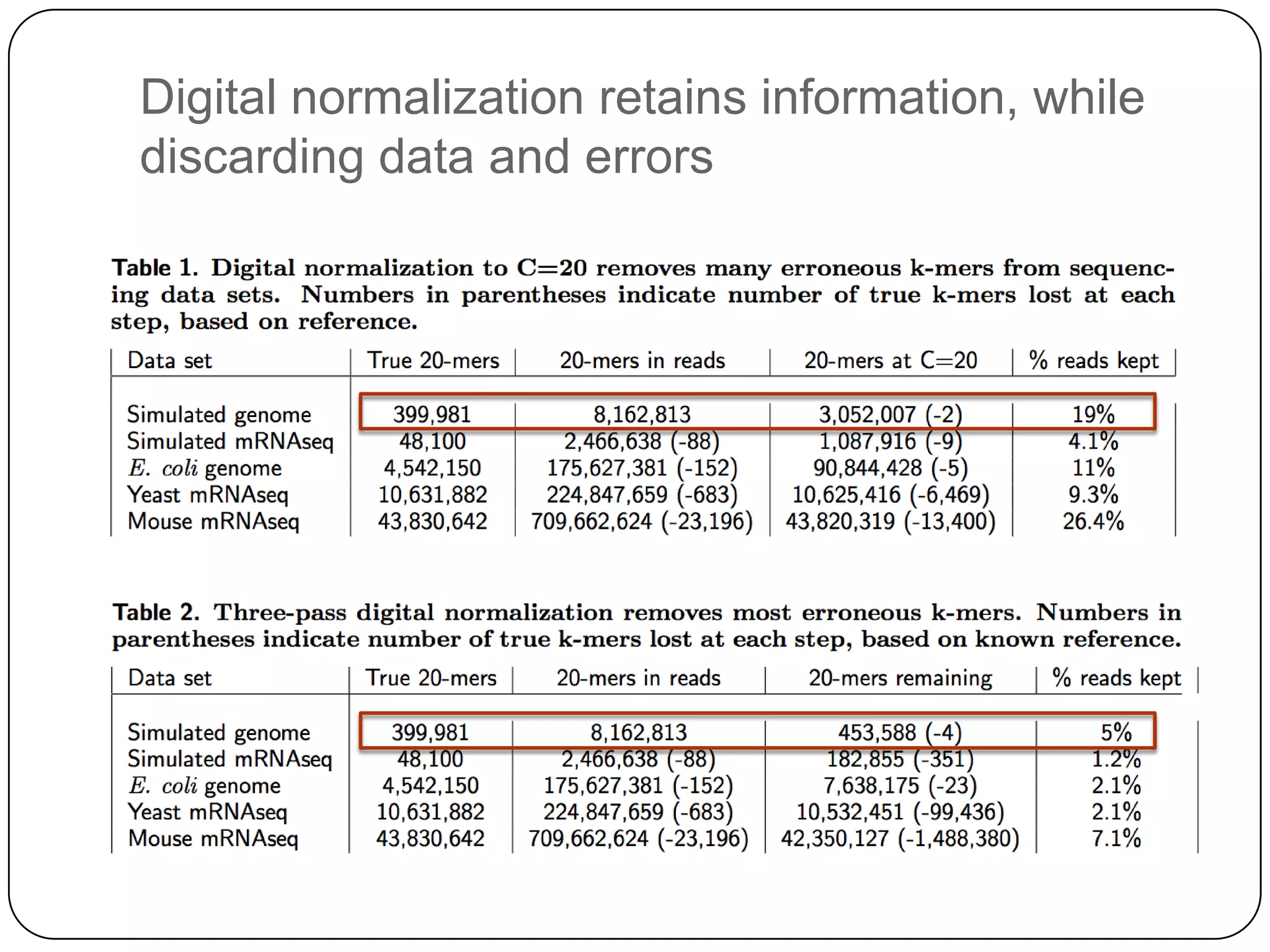

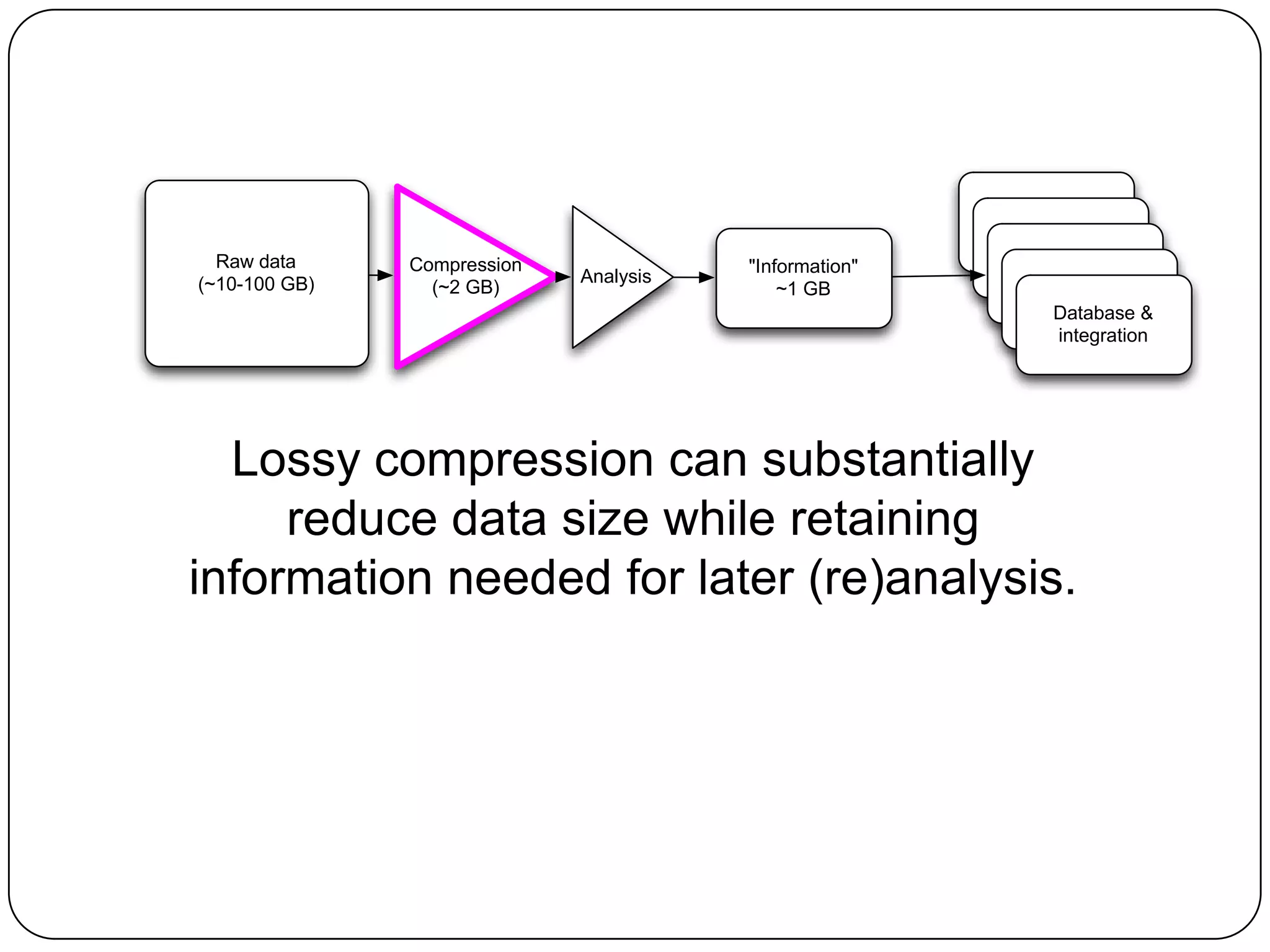

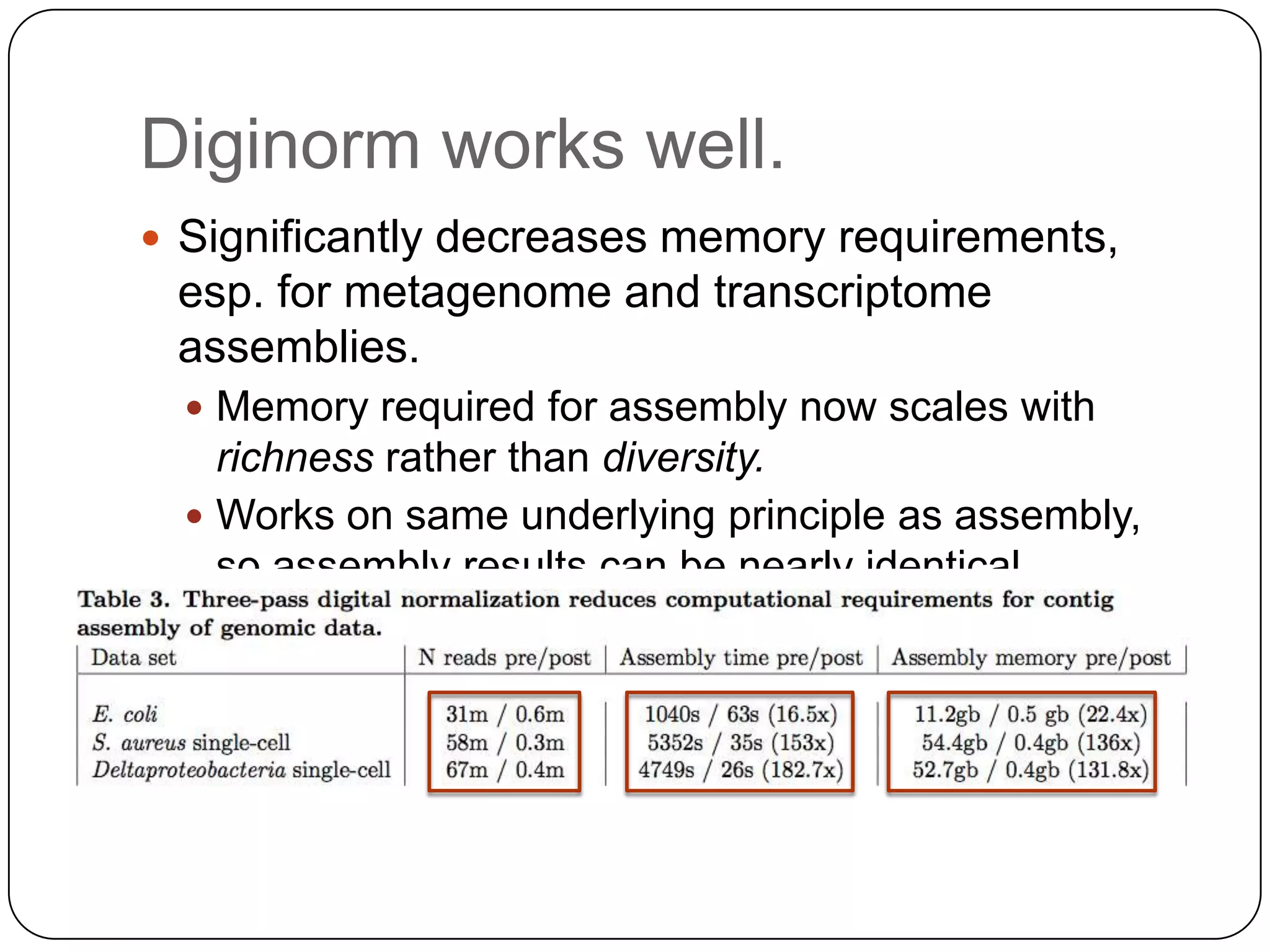

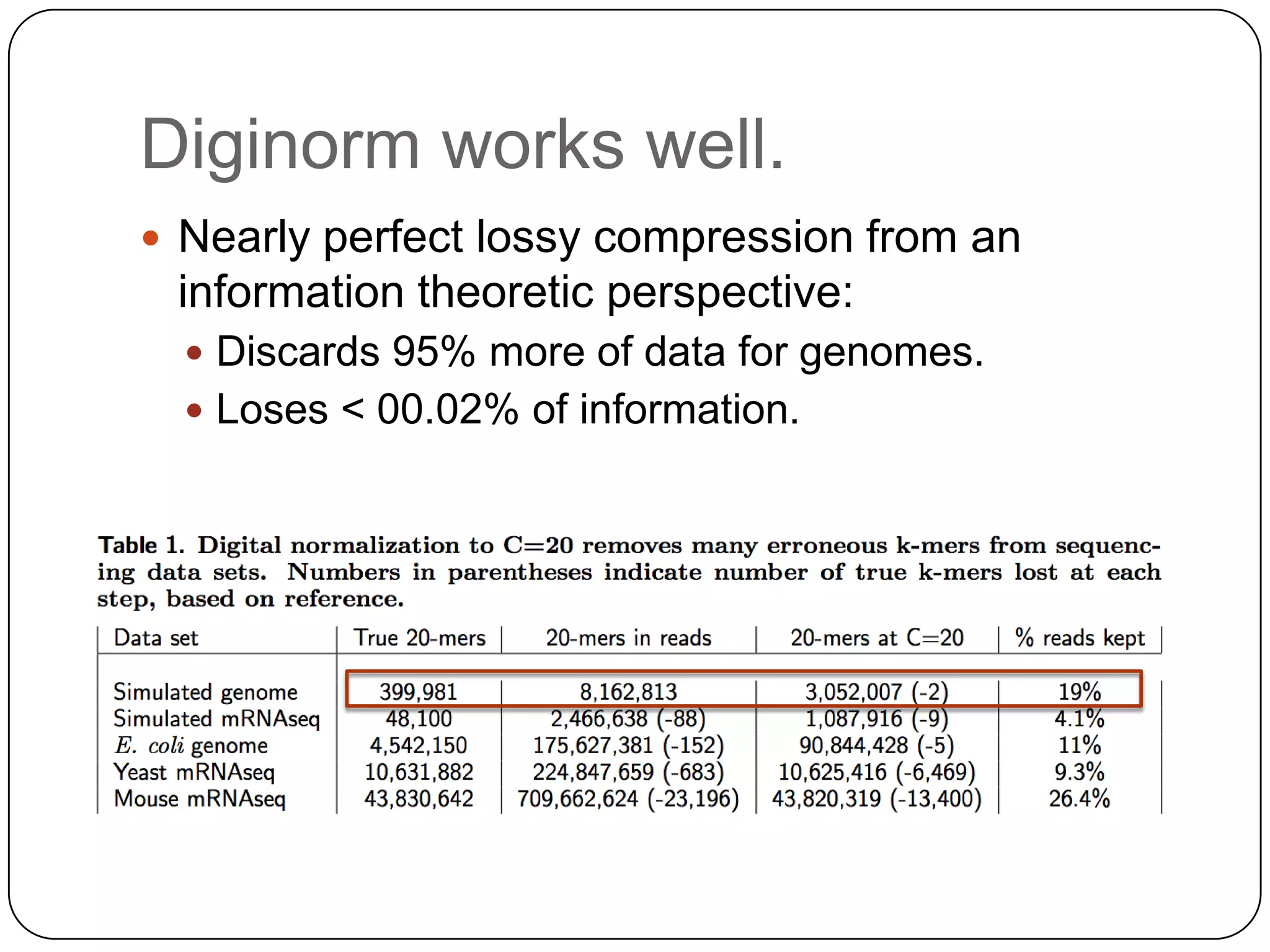

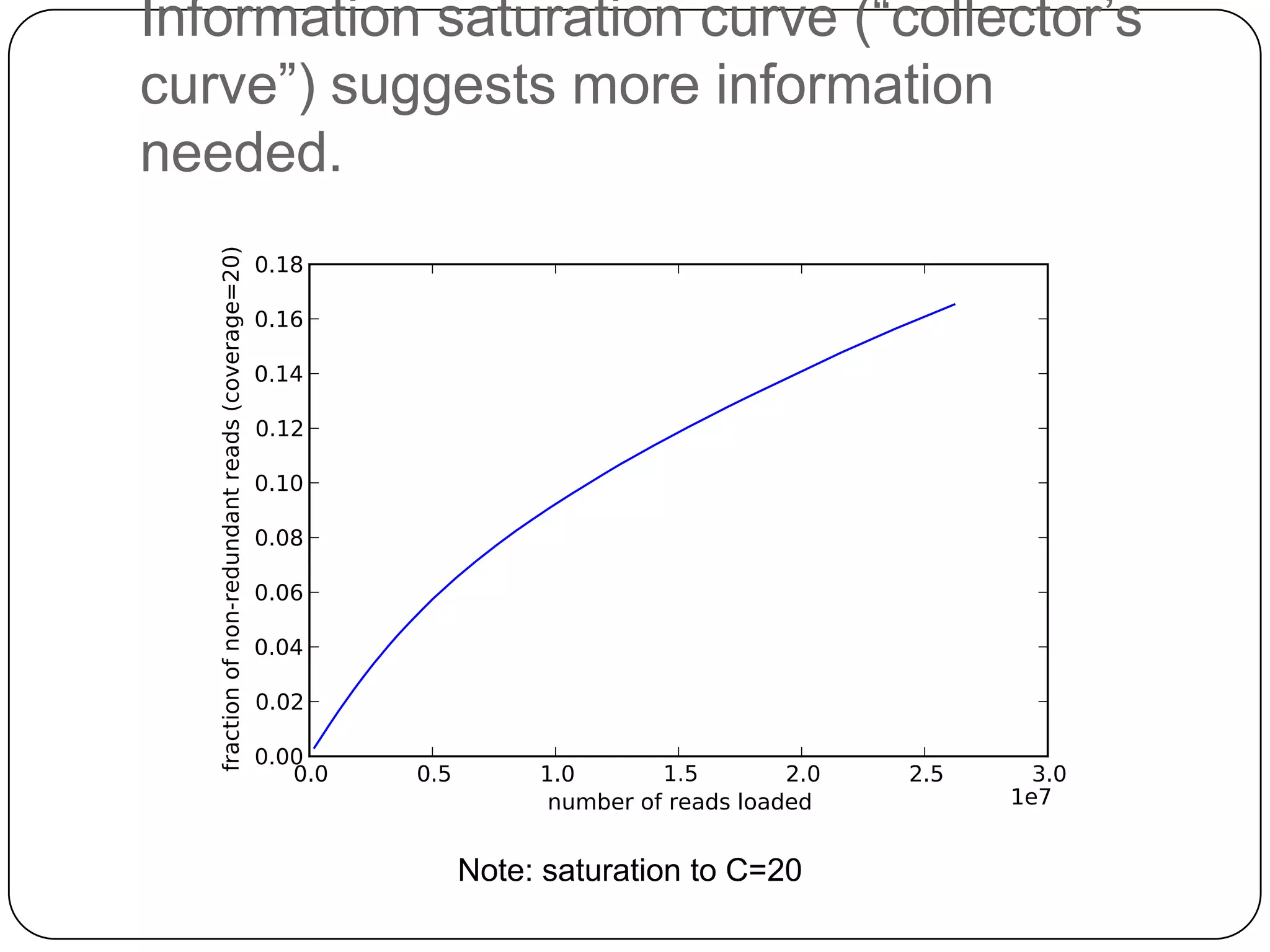

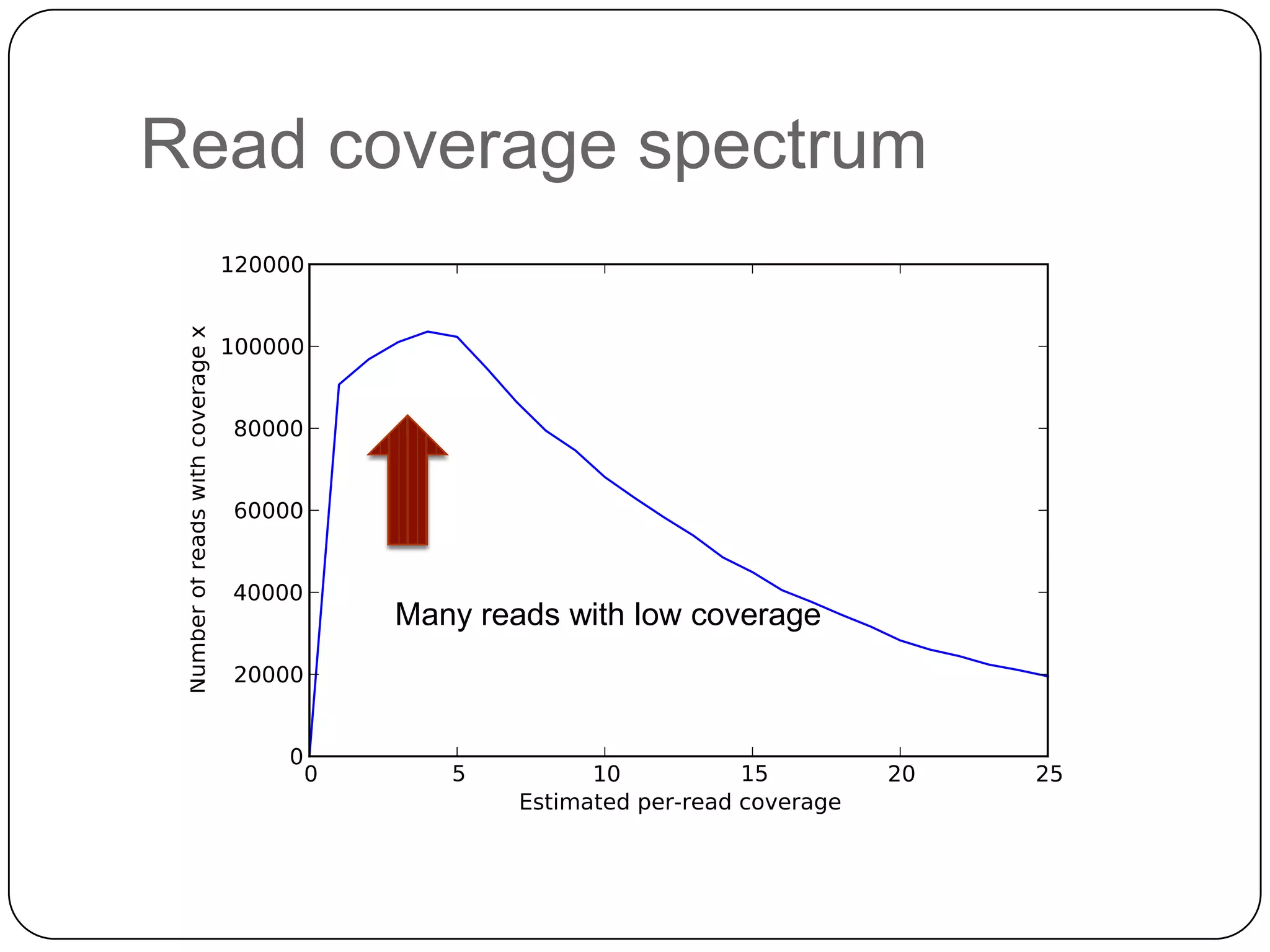

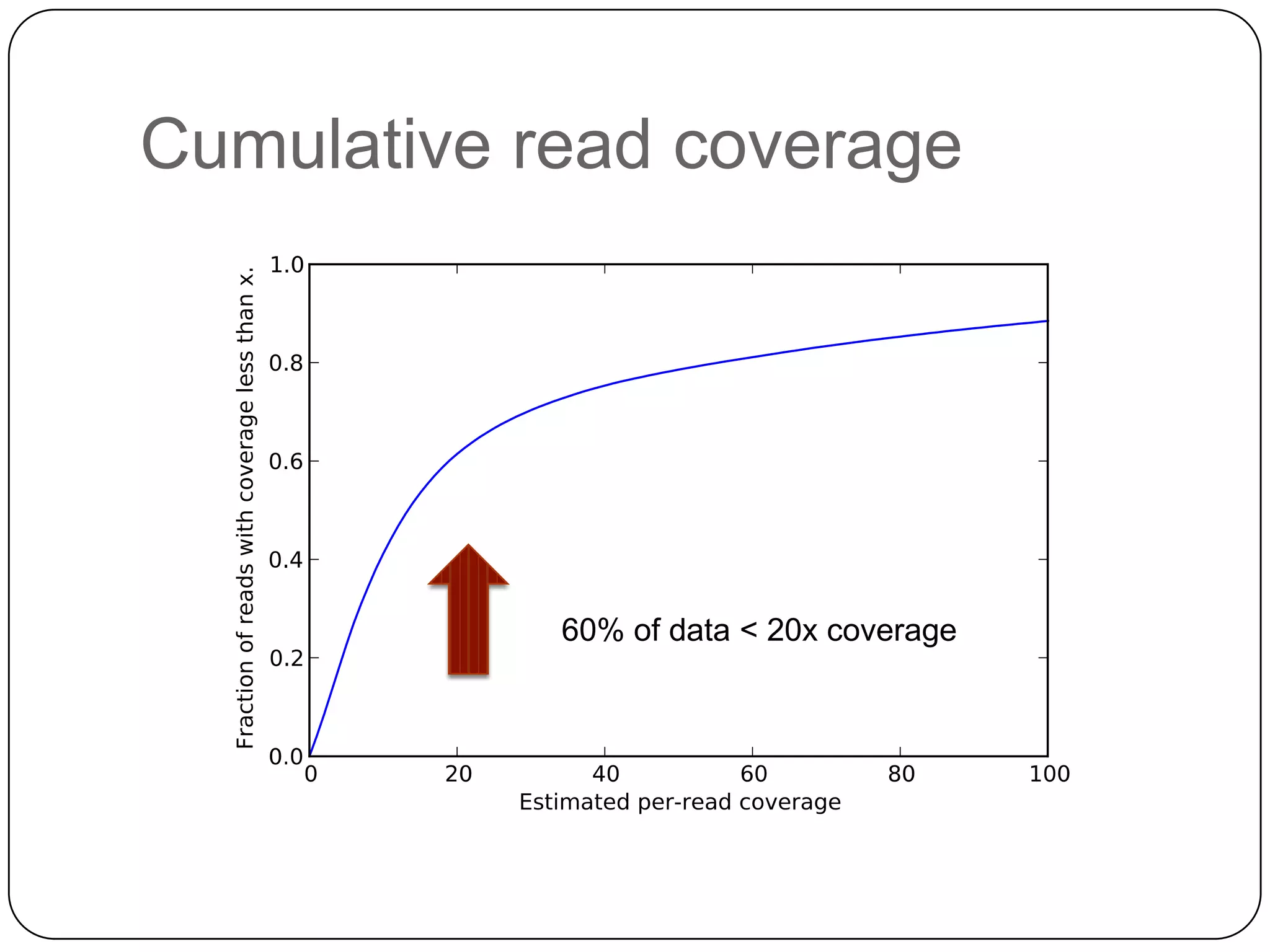

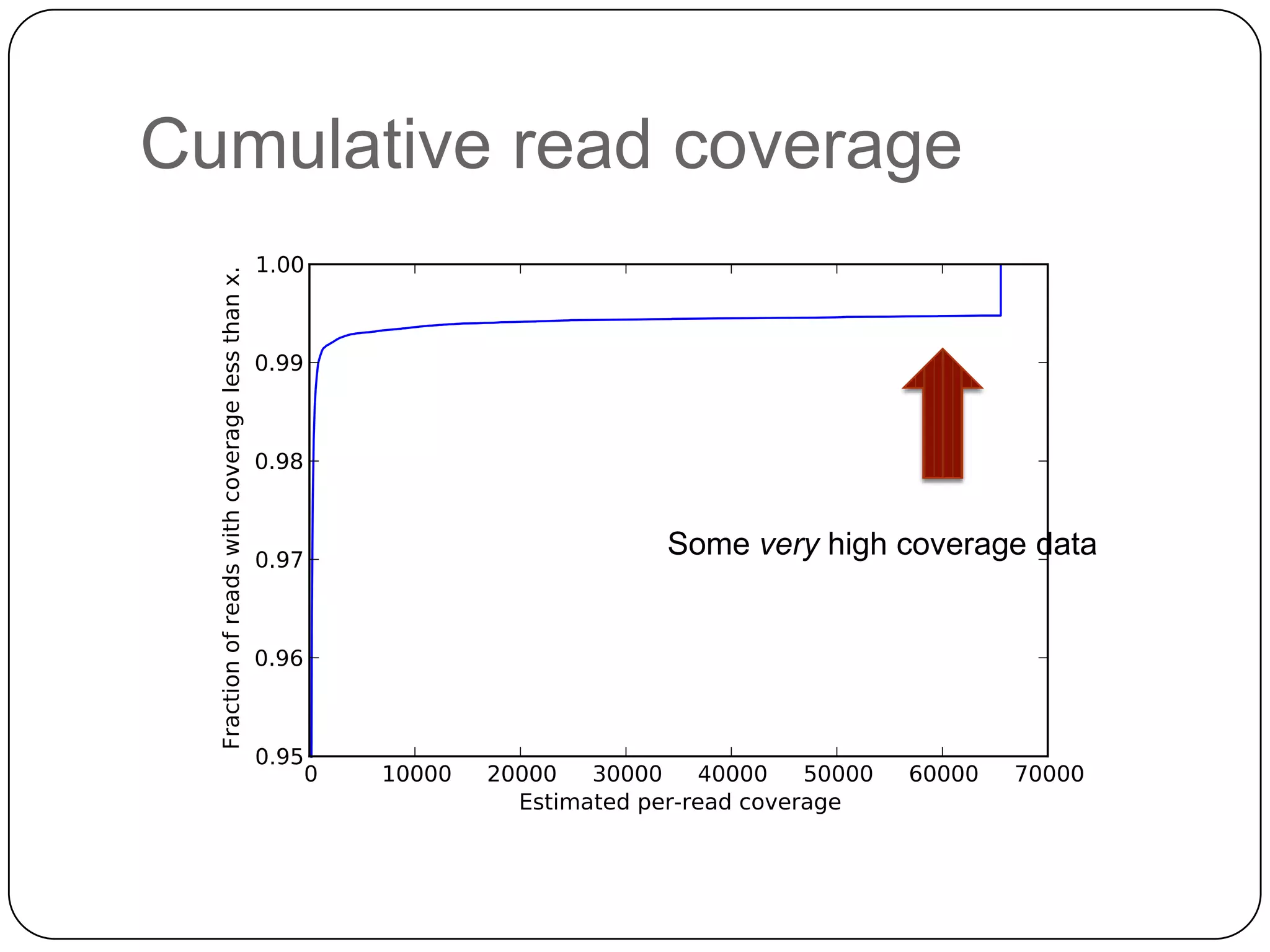

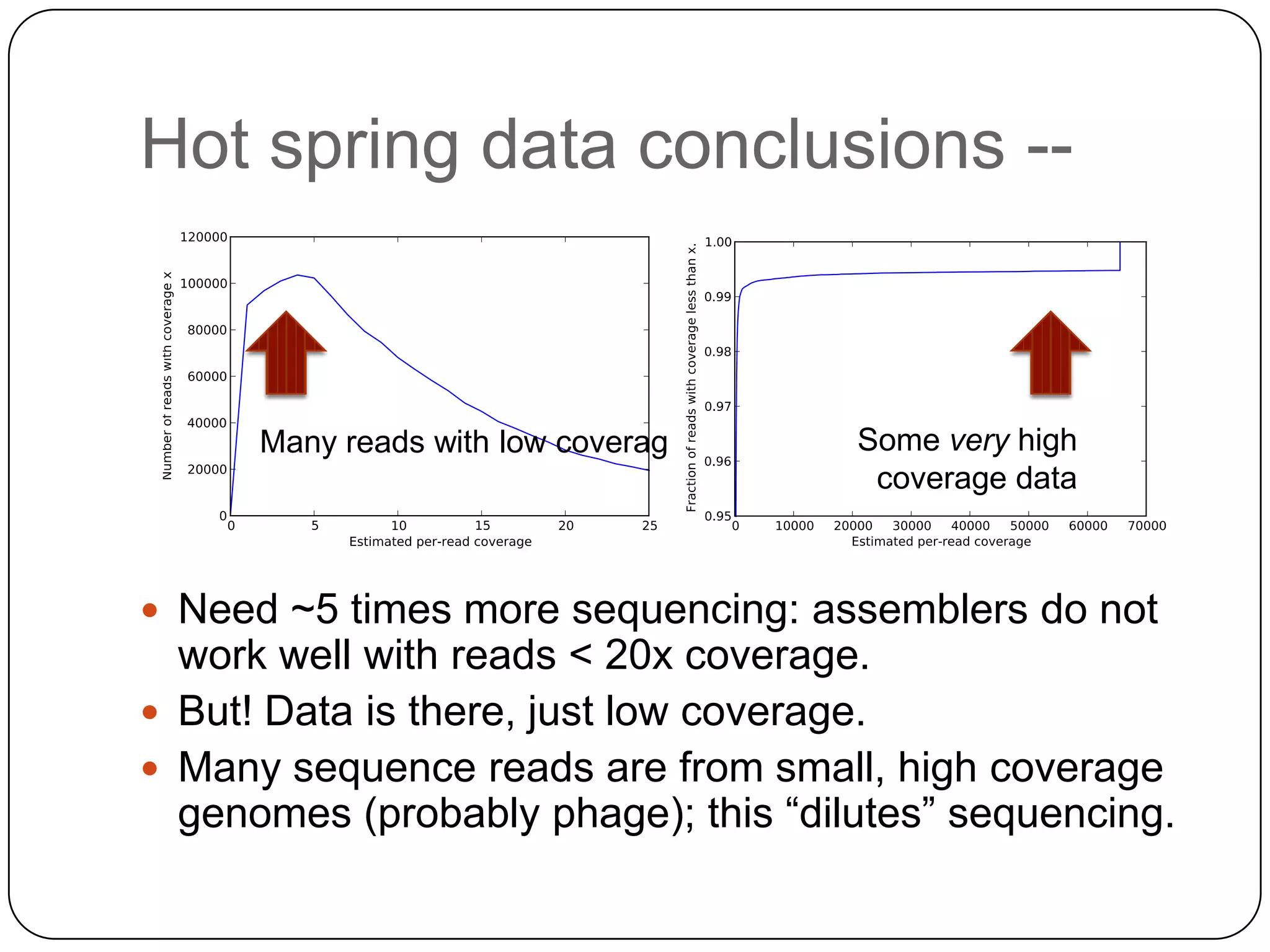

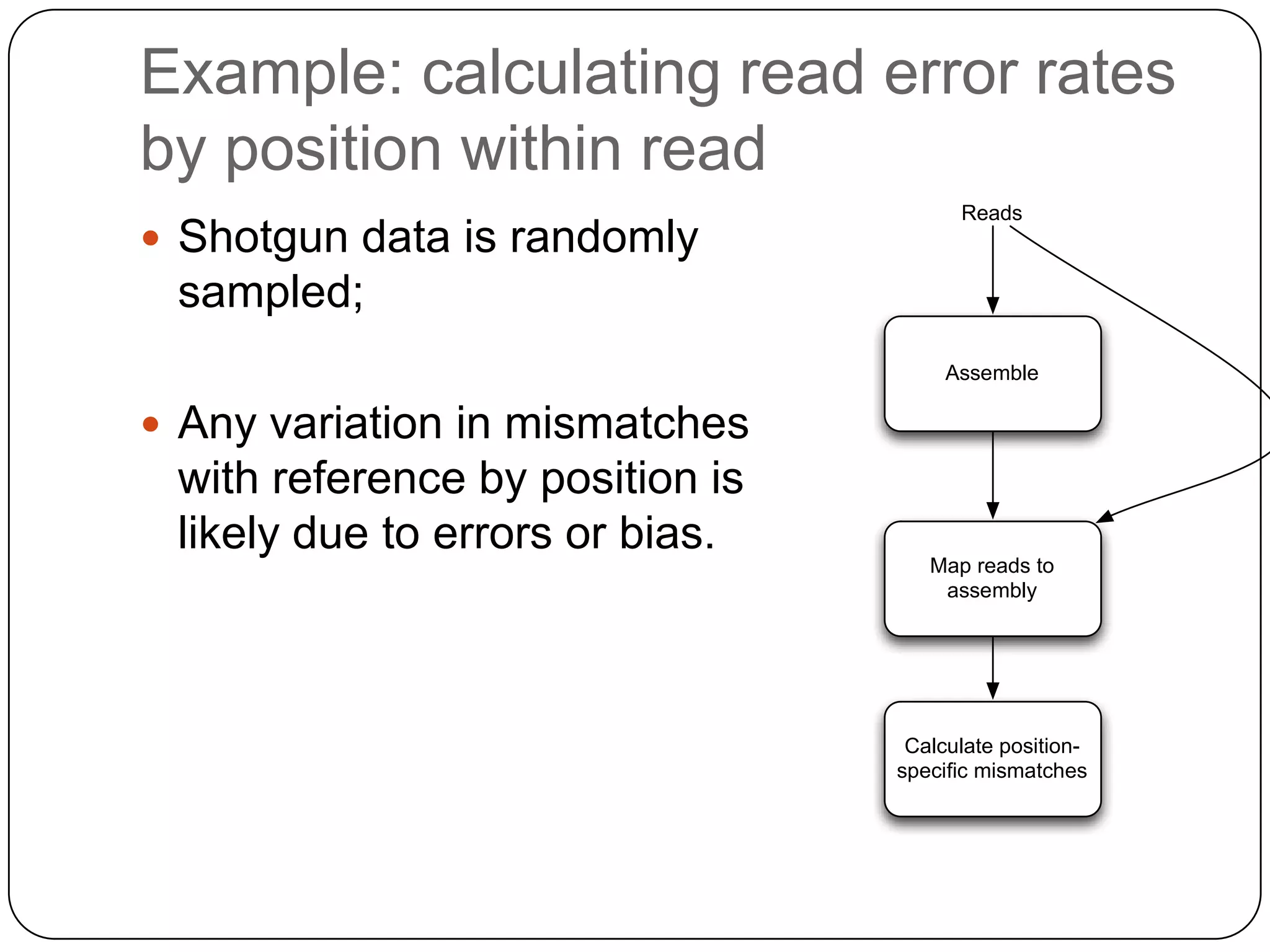

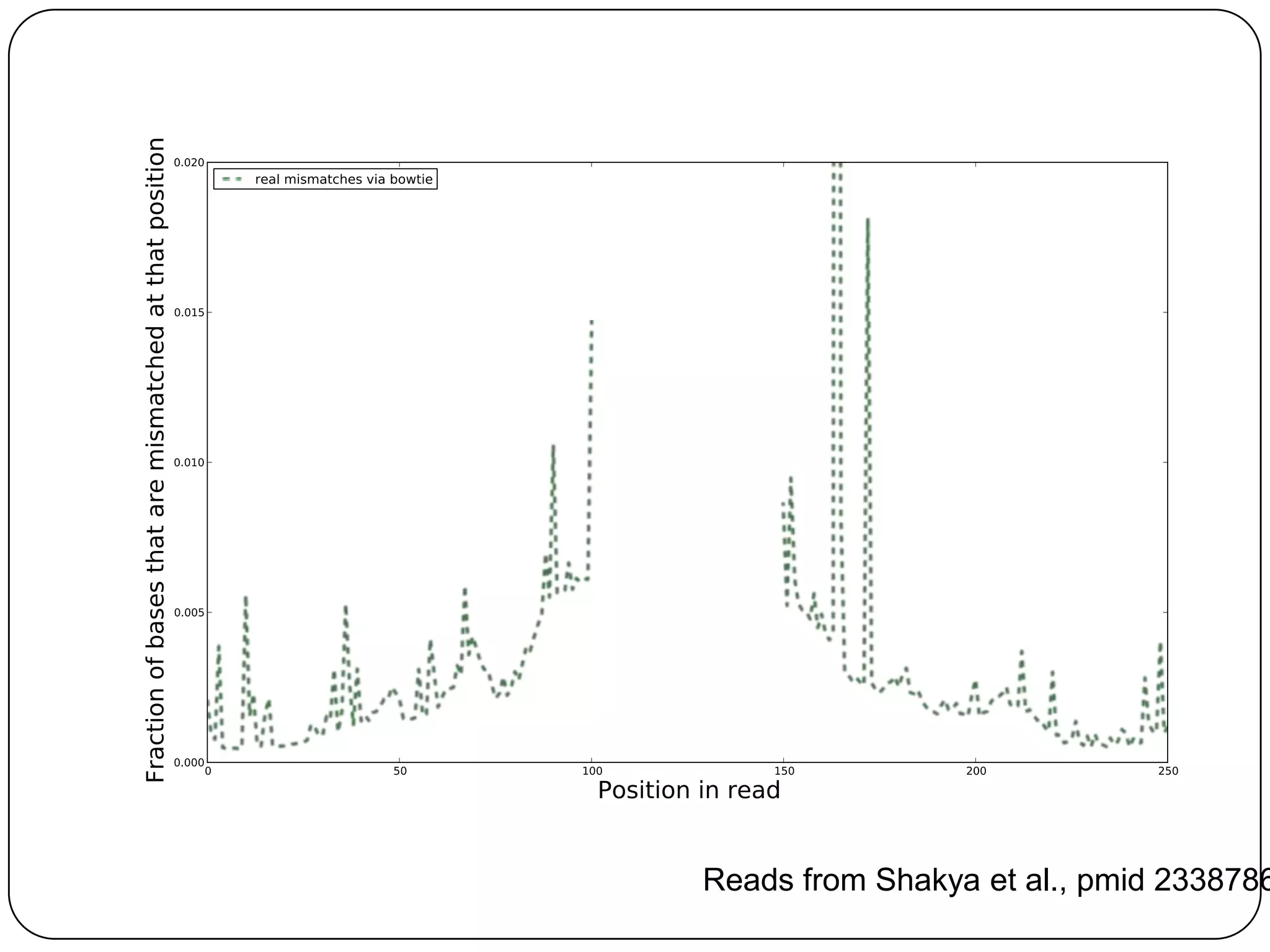

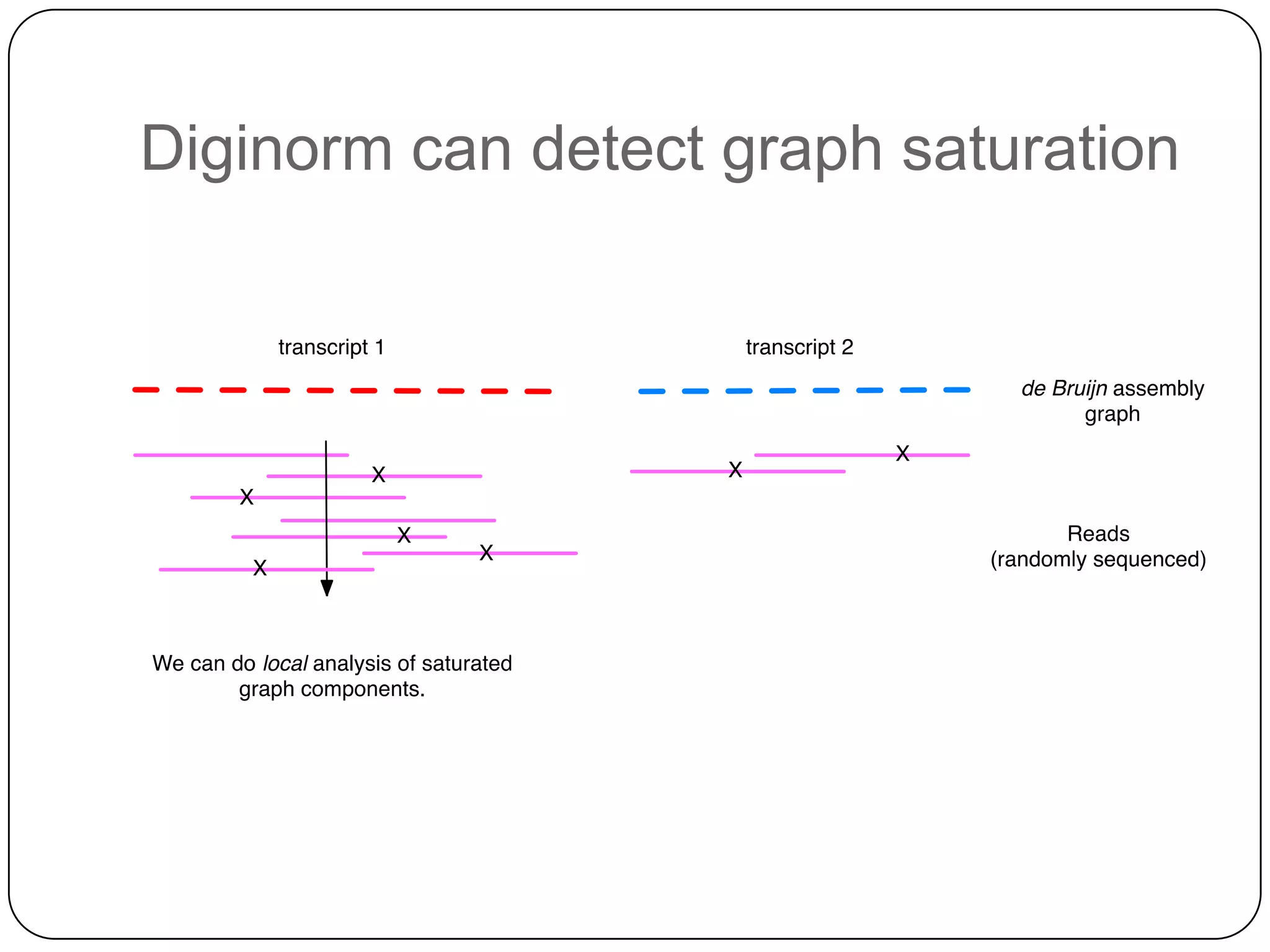

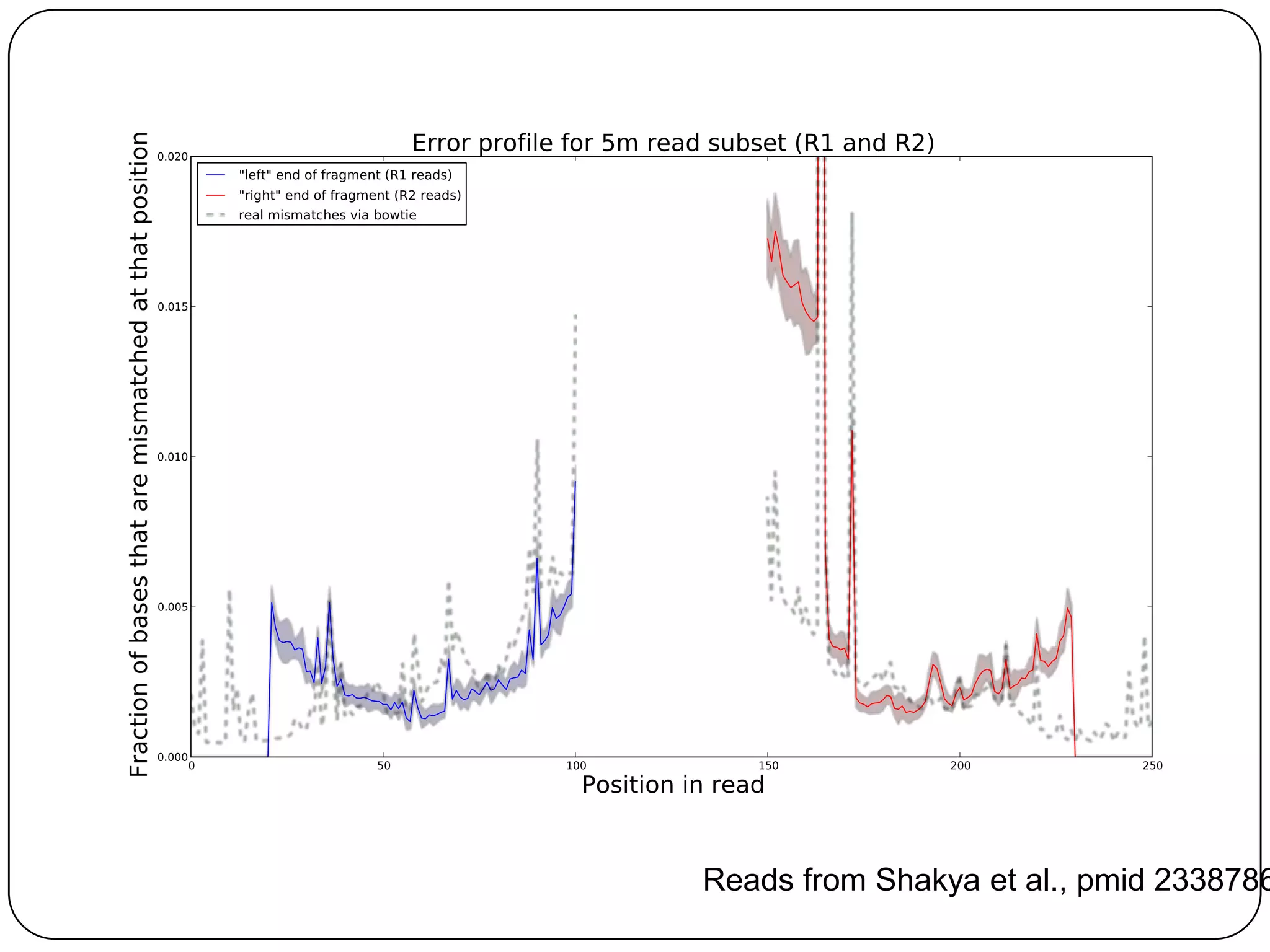

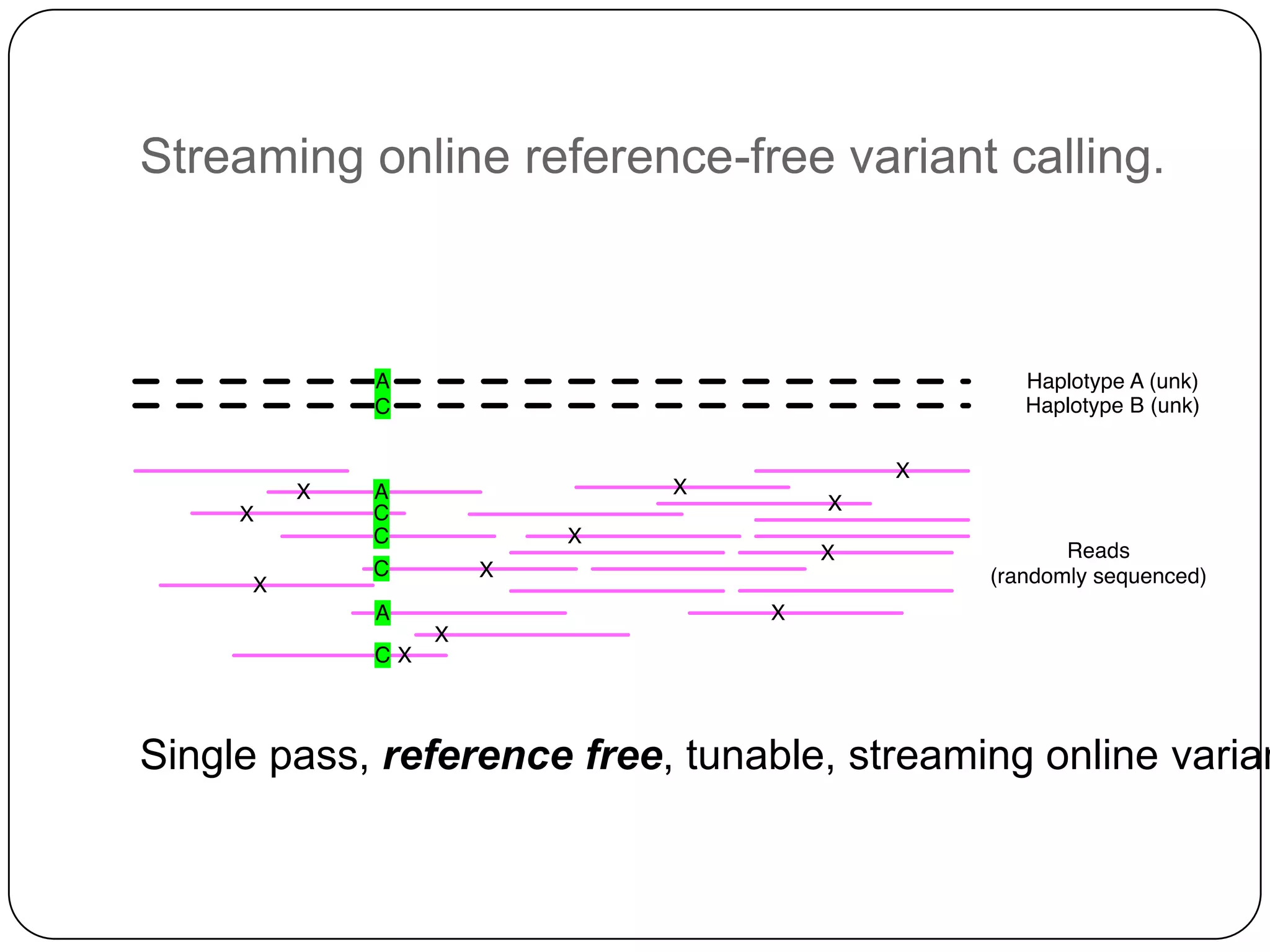

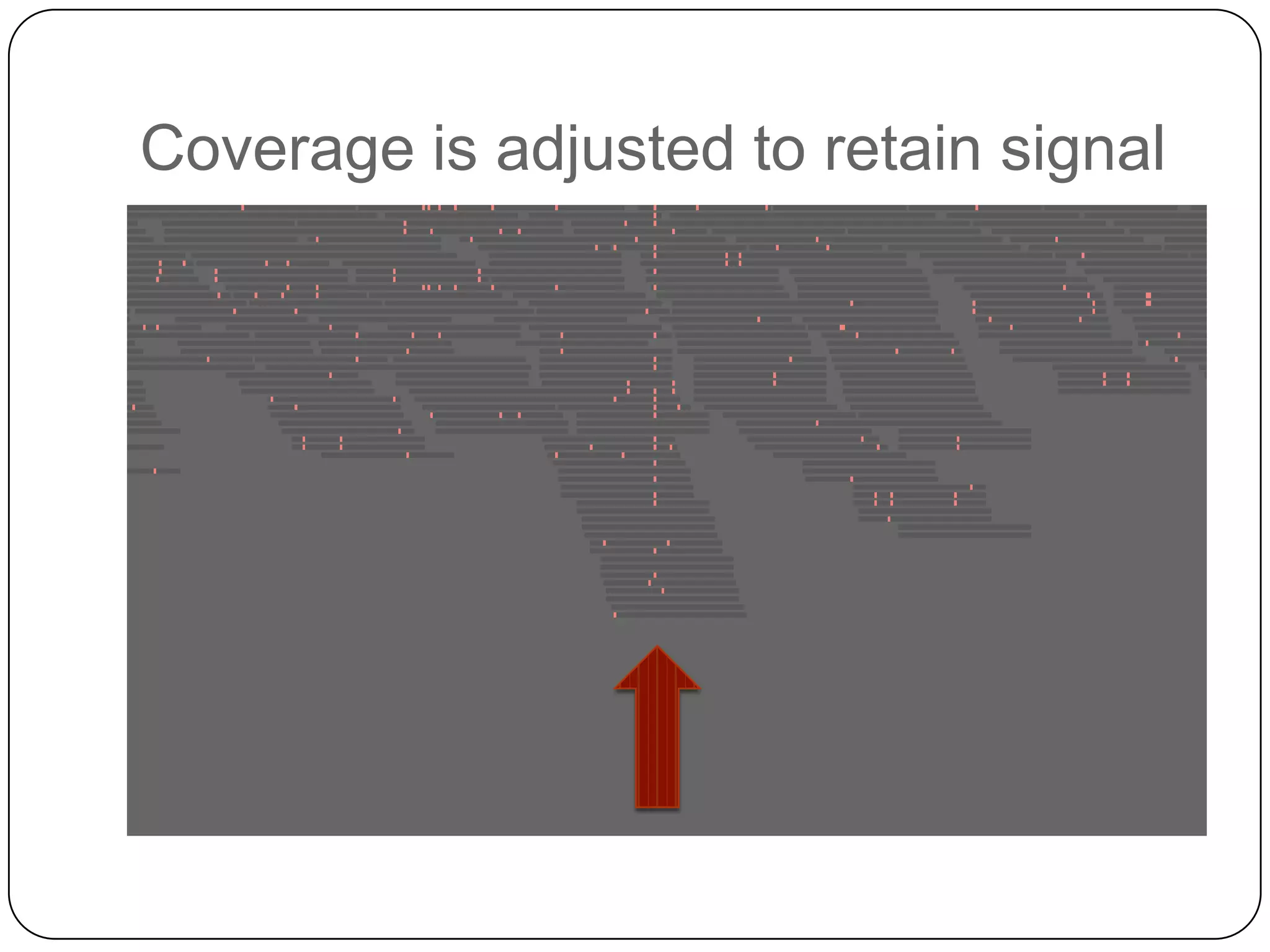

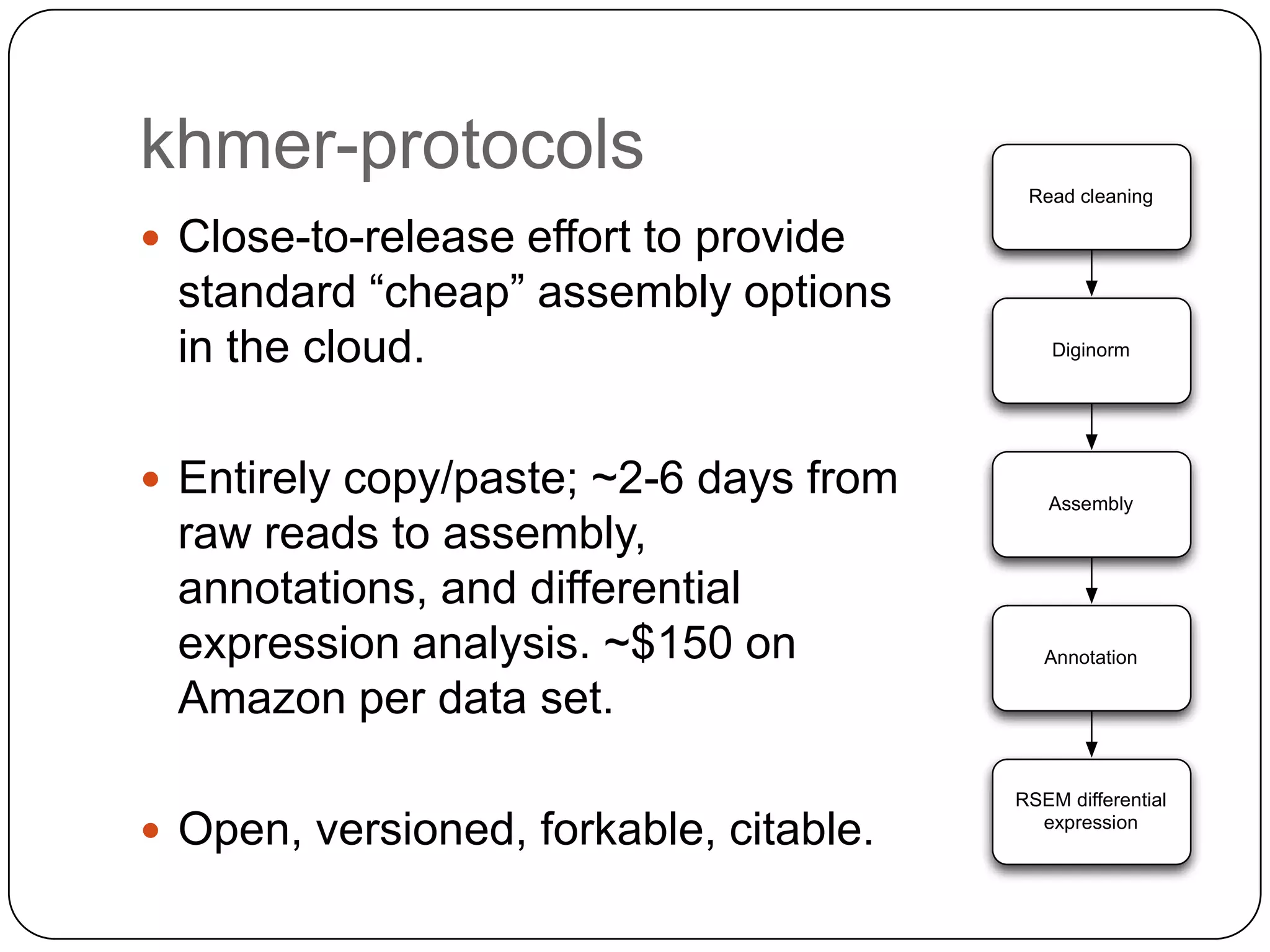

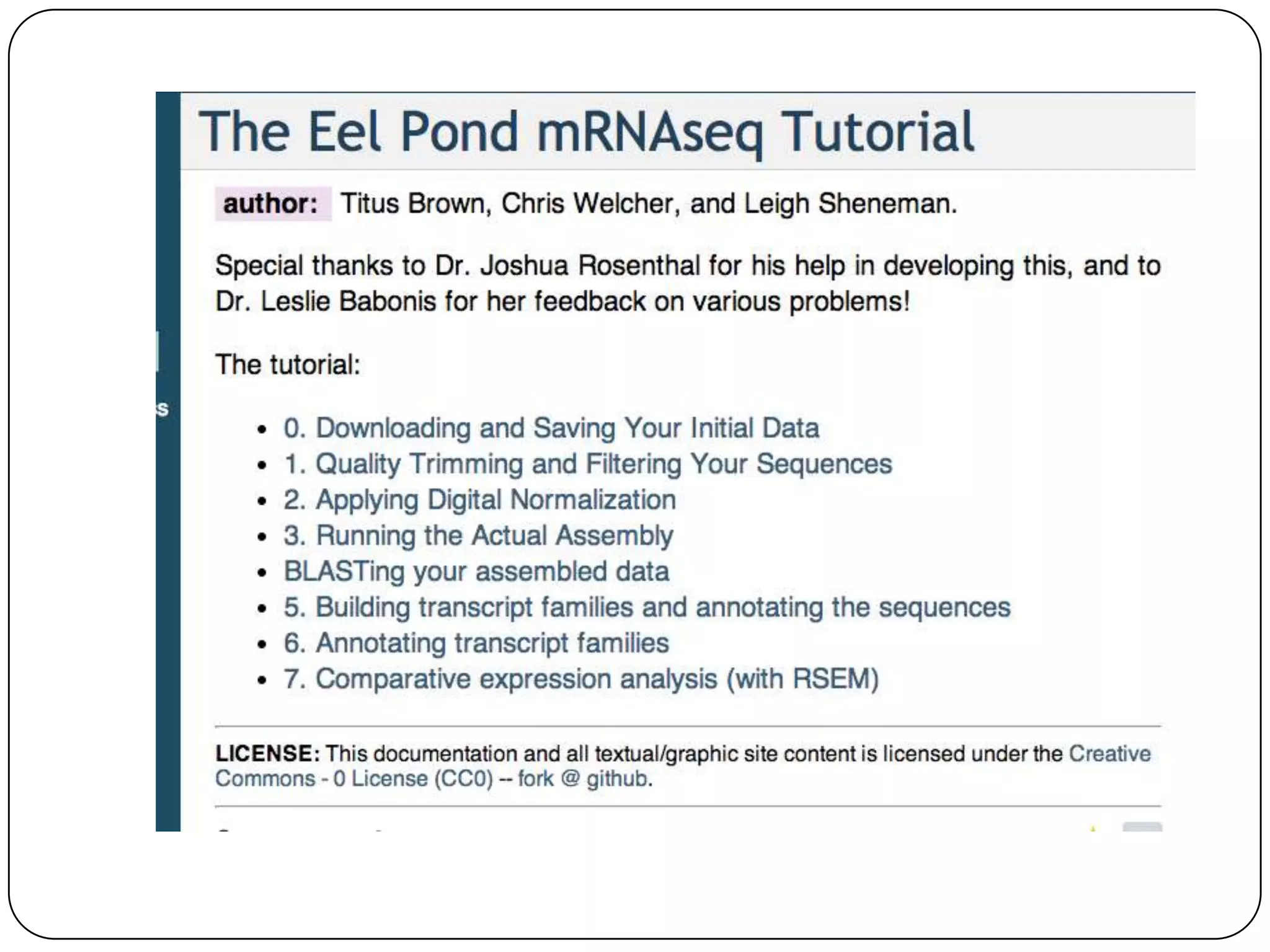

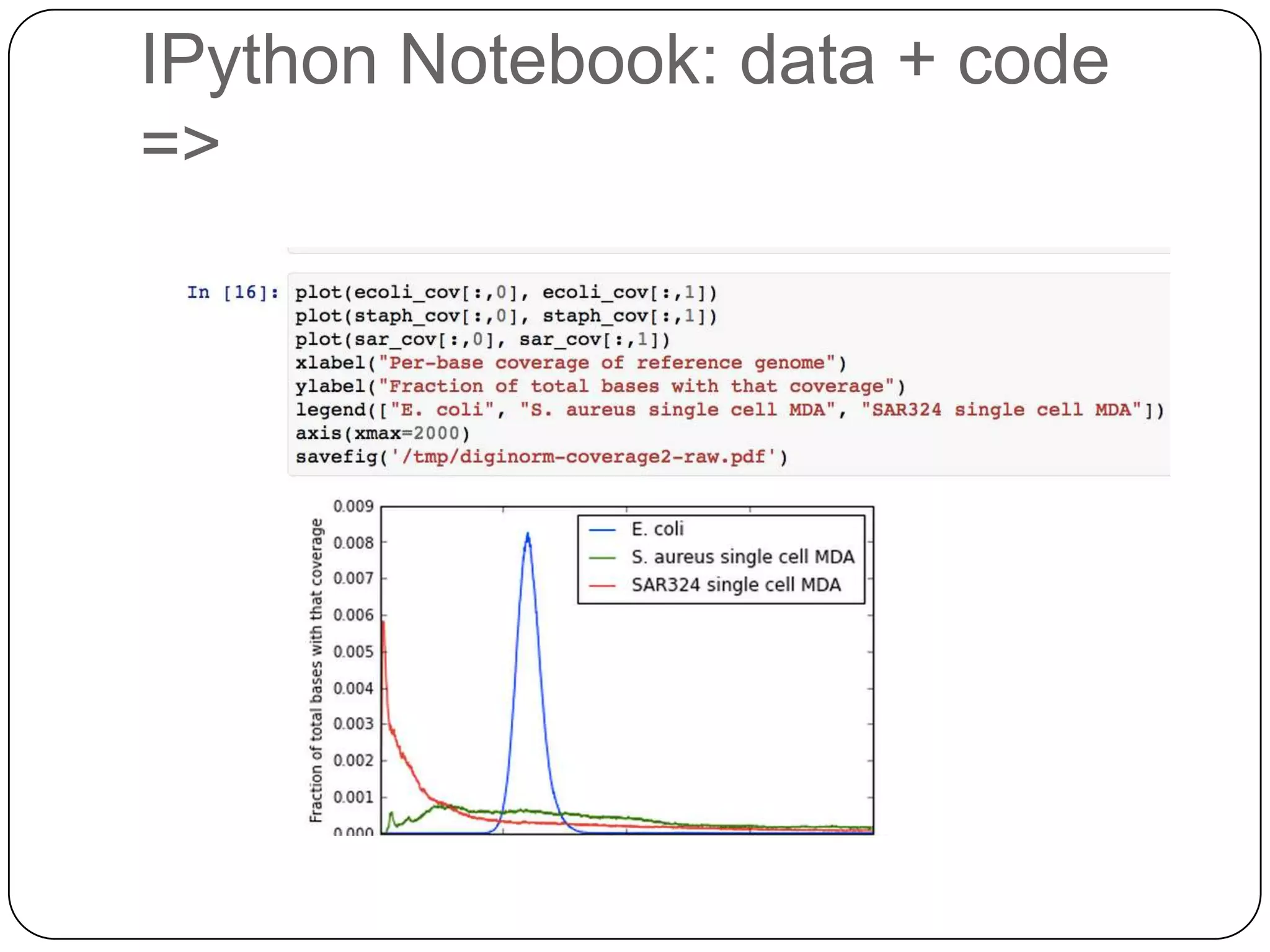

Digital normalization provides a computationally efficient way to filter high-coverage reads from shotgun sequencing data, reducing data size while retaining most of the information needed for downstream analysis. It works by estimating the coverage of each read without using a reference genome and discarding reads above a given coverage cutoff. The method has been shown to significantly decrease memory requirements for de novo assembly of various data types like metagenomes and transcriptomes, while producing similar or improved assembly results. Future work includes developing reference-free methods for analyzing sequencing data in a streaming fashion before or without assembly.